When trying to try officials, the unanswered question is whether the act is criminal

When Thomas Jefferson took office on March 4, 1801, he inherited a hostile judiciary. Predecessors George Washington and John Adams had packed the federal bench with jurists whose views clashed sharply with the new president’s. Jefferson particularly chafed at the enthusiasm with which these Federalist judges had enforced the Sedition Act, which had outlawed criticism of the government. Jefferson wanted to remove these conservative judges and replace them with jurists sharing his far more liberal views—but how?

Federal judges serve for life. Like presidents, these officeholders can be removed only by impeachment, a process the Constitution limits to individuals the Senate finds to have committed treason, bribery, or “other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” The judges so vexing to Jefferson were rabid partisans who had flaunted their politics in the courtroom. However, none had engaged in criminal conduct. Impeachment and removal would hinge on whether the term “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” includes non-criminal conduct. As Jefferson soon learned, there was—and is—no simple answer.

The men who met in Philadelphia in 1787 to draft the Constitution knew the United States needed a means of ousting federal officials found to have abused their positions. The delegates, having endured the rule of an unremovable British monarch, at first focused on impeachment of an errant president. “Should any man be above Justice?” asked George Mason of Virginia. “Above all shall that man be above it, who can commit the most extensive injustice?” Without a vehicle for peaceable removal of the chief executive, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania noted, the recourse could be violence. If that occurred, said Edmund J. Randolph of Virginia, the result would be “tumults & insurrections.” Delegates saw impeachment proceedings as a high-reward/low-risk proposition. “A good magistrate will not fear them. A bad one ought to be kept in fear of them,” said Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts. Realizing that holders of other governmental positions might abuse their positions, the delegates expanded the list of officials subject to impeachment from the president alone to the “President, Vice President and all civil Officers of the United States.”

The delegates entrusted the removal mechanism to Congress. A majority vote by the House is called impeachment, but impeachment is only the filing of formal charges, known as articles of impeachment, enumerating the proffered grounds for removal. To oust a president or other official from office, the Senate must, by a two-thirds majority, convict that official of the stipulated impeachable offense or offenses.

The tougher question was how to define impeachable offenses. Delegates rejected vague standards like “malpractice or neglect of duty,” “corruption,” and “maladministration.” They agreed on treason and bribery but wanted something more. Since 1386, the English parliament had been using the term “high crimes and misdemeanors” as grounds for removal of royal officials for a wide range of misconduct, including misapplication of funds, neglect of duty, and abuse of power. On September 8, 1787, after having met for more than three months in the brutal Philadelphia heat, the Convention delegates added, without debate, “high Crimes and Misdemeanors” as a catch-all impeachable offense. That ringing phrase lacked precision but satisfied the exhausted delegates, who also decided that even after being impeached and convicted, an official wouldn’t be home free. He could also be “liable and subject to Indictment, Trial, Judgment and Punishment, according to Law,” they declared, without deciding whether a sitting president can be indicted or tried in criminal court.

After the Constitutional Convention, delegates explained what conduct they took to be impeachable. To Alexander Hamilton of New York and Charles Pinckney of South Carolina, such offenses required an abuse of the public trust. A discussion between Mason and James Madison at Virginia’s ratification convention offered a detailed example. Mason told Madison he feared a presidential malefactor might pardon accomplices. If he did so early enough, Mason said, the president in question could prevent an investigation of his own misconduct. Nonsense, Madison replied. “[I]f the President be connected, in any suspicious manner, with any person, and there be grounds to believe he will shelter him,” Marshall said, “the House of Representatives can impeach him.”

Within a decade, Congress was encountering its first impeachment case. In 1797, Senator William Blount, Democratic-Republican of Tennessee, had hatched a plot to help England wrest Louisiana from Spain. Spain and England were at war, but the United States was at peace with each. This meant that Blount’s conspiracy violated American neutrality laws. On July 8, 1797, the House voted to impeach the Tennessean. The Senate expelled Blount the next day. On January 11, 1799, the upper body dismissed the impeachment charges, presumably because Blount no longer held office.

Defeating Federalist incumbent John Adams in the 1800 election,

Jefferson took office the following March warily eyeing the federal bench. Federalist judges were, a newspaper noted, “partial, vindictive, and cruel”—and, in Jefferson’s eyes, wielders of immense power. The Constitution “is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist, and shape into any form they please,” he said. With such a judiciary in place, the president feared, “all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased.” Political reality militated against precipitous action. Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party controlled the House 65-40, with one seat vacant. In the Senate, however, the Federalists retained a slim 17-15 majority. Before Jefferson could begin his campaign, he needed a Federalist judge to misbehave in a way that unequivocally demanded impeachment.

Even before the 1800 election, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase had begun building a case against himself. Born in 1741, Chase had served in the Continental Congress and had signed the Declaration of Independence. However, he had “an oversized ego, and his irascibility had won him many enemies,” historian John B. Boles noted. In those days, Supreme Court justices rode the circuit, overseeing matters in the lower federal courts. In May 1800, Chase was traveling to a courtroom in Richmond, Virginia. During his trip, he read The Prospect Before Us, a political pamphlet written by James T. Callender. Callender, a professional rabble-rouser, at the time was vociferously pro-Jefferson and viciously anti-Federalist; in fact, Jefferson had encouraged him and sent him money. In publishing Prospect, Callender plunged vigorously into the 1800 campaign. Voters faced a choice “between Adams, war and beggary, and Jefferson, peace and competency,” he wrote in his tract.

As Chase read Callender’s attacks on Adams in Prospect, his “indignation was strongly excited, by the atrocious and profligate libel,” the jurist later said. Chase vowed to do something about Callender, and he had the means. In 1798, Congress had enacted the Sedition Act, making it a crime to publish “any false, scandalous, and malicious writing” about the president or the federal government.

On May 24, 1800, Chase persuaded a Virginia grand jury to charge Callender with sedition. The indictment cited 20 anti-Adams passages in The Prospect Before Us. These included a characterization of the Adams presidency as “one continued tempest of malignant passions,” descriptions of Adams as a “hoary headed incendiary” and “a professed aristocrat,” and an accusation that Adams had “contrived pretences to double the annual expense of government by useless fleets, armies, sinecures and jobs of every possible description.”

Presiding at Callender’s trial in Richmond, Chase behaved less like a judge than an out-of-control prosecutor. He denied Callender time to prepare a defense, barred a key defense witness from taking the stand, badgered defense counsel, refused to disqualify a juror who admitted bias, and told the jury he thought Callender guilty.

On June 3, 1800, after deliberating two hours, the jury convicted Callender. Chase sentenced the pamphleteer to nine months in jail and fined him $200. Callender served his time and was released on March 3, 1801, the day before Jefferson took office and the day the Sedition Act expired. Two weeks later, the new president, who loathed the Sedition Act, pardoned Callender. As a reward for reviling Adams, the journalist expected Jefferson to name him postmaster of Richmond. Jefferson refused, prompting Callender to turn on his former patron with the same gusto he had shown Jefferson’s foes. In 1802, Callender published a series of articles alleging that Jefferson had had a sexual relationship with his slave, Sally Hemings.

In 1802, John Pickering, a federal trial judge in New Hampshire, offered Jefferson a sitting-duck target for impeachment. Even before being appointed to the federal bench in 1795, Pickering, author of New Hampshire’s Constitution, had been known for erratic behavior, and his conduct had worsened.

In October 1802, a Democratic-Republican customs official at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, alleging customs violations, seized the ship Eliza. The ship’s owner was a prominent Federalist to whom Pickering immediately returned the vessel. The same customs official filed suit to re-seize the ship and to collect penalties. The trial began on November 11, 1802, with Pickering in no condition to proceed. He “exhibited every mark of intoxication; staggered and reeled, spoke in a thick way,” said court clerk Jonathan Steele. Pickering threatened to give a “damn’d Caning” to an attorney who had displeased him, and when court adjourned for the day, remarked, “I shall be sober in the Morning. I am now damned drunk.” The next morning, the judge was “equally deranged or intoxicated,” deputy marshal Thomas Chadbourn noted. Pickering complained about having to decide “such damn’d paltry matters” and declared, “if we sit here four thousand years the ship will still be restored.” The prosecutor argued that customs duties bring the government revenue. “Damn the revenue,” the judge replied. “I get but a thousand dollars of it.” Pickering returned the Eliza to its Federalist owner, a ruling seen as blatant political favoritism.

The prosecutor, livid, collected affidavits from witnesses to the spectacle and sent this documentation to Jefferson. On February 3, 1803, the president referred the matter to Congress. Pickering’s removal was “not within Executive cognizance,” Jefferson wrote in his transmittal letter, but the House has “the power of instituting proceedings of redress.” Privately, Jefferson told a friend, he thought Pickering’s antics to be “sufficient cause of removal without further enquiry.” On March 2, 1803, the House, voting 45-8, impeached Pickering and sent the case to the Senate for trial. The articles of impeachment accused Pickering of illegally returning the Eliza to its owner, presiding at trial “in a state of total intoxication, produced by the free and intemperate use of intoxicating liquors,” and speaking in court “in a most profane and indecent manner…to the evil example of all the good citizens of the United States.”

While a Senate trial was pending against Pickering, Chase gave the Democratic-Republicans more ammunition against himself. On May 2, 1803, while riding the circuit in Maryland, Chase turned an occasion for routine legal instructions to a Baltimore grand jury into a political tirade against Jefferson and principles the president held dear. Chase attacked “the modern doctrines by our late reformers, that all men in a state of society are entitled to enjoy equal liberty and equal rights.” He repudiated as the musings of “visionary and theoretical writers” the unalienable rights set forth in the Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson had written, and which Chase had signed. An expanded right to vote in Maryland, Chase told grand jurors, would cause society to “crumble into ruins before many years elapse.”

The press reported Chase’s speech, with the National Intelligencer calling his words “the most extraordinary that the violence of federalism has yet produced.” Jefferson agreed. On May 13, 1803, the president wrote to Representative Joseph H. Nicholson (DR-Maryland), asking, “[O]ught this seditious & official attack on the principles of our constitution, and on the proceedings of a state, to go unpunished?” Although Jefferson told Nicholson “it is better that I should not interfere,” his letter clearly was a call for action against Chase.

However, Pickering was first in line. The Senate began Pickering’s impeachment trial on March 2, 1804. The 66-year-old jurist, said to be too ill to make the 12-day journey from New Hampshire to Washington, did not appear. The Senate tried him in absentia. Pickering’s defense, offered by proxy, was that he was insane, as certified by an examining physician who found the judge to be “wild, extravagant, and incoherent.” While Pickering was unfit to sit on the bench, however, he had committed no crime. The question was whether non-criminal conduct constituted a high crime or misdemeanor, a quandary for the Federalists.

The Federalists didn’t want to allow Jefferson to use impeachment to remove Federalist judges for non-criminal conduct. In addition, they suspected the Pickering case was a warm-up for proceedings against Chase and other compatriots. The Federalists also knew Pickering was unfit to serve. However, in a bid to limit the removal power, they insisted the government allege the commission of a crime. If non-criminal conduct could be invoked to justify impeachment, Senator Samuel White, Federalist of Delaware, argued, “every officer of the Government must be at the mercy of a majority of Congress.” Since impeachment was the only way to remove a judge, Federalists by default were willing to tolerate, in the words of historian Lynn W. Turner, “monstrous misgovernment of courts presided over by irremovable lunatics” like Pickering.

Jeffersonians, now holding a 25-9 Senate majority, had an easy target in Pickering. They employed his case to propel an expansive reading of the rubric “high Crimes and Misdemeanors.” If Pickering’s non-criminal conduct did not suffice to justify removal, asked Senator James Jackson (DR-Georgia), “How shall we get rid of the Judge?” To Senator George Logan (DR-Pennsylvania), Pickering’s misbehavior, criminal or not, imposed on the Senate a duty to remove him.

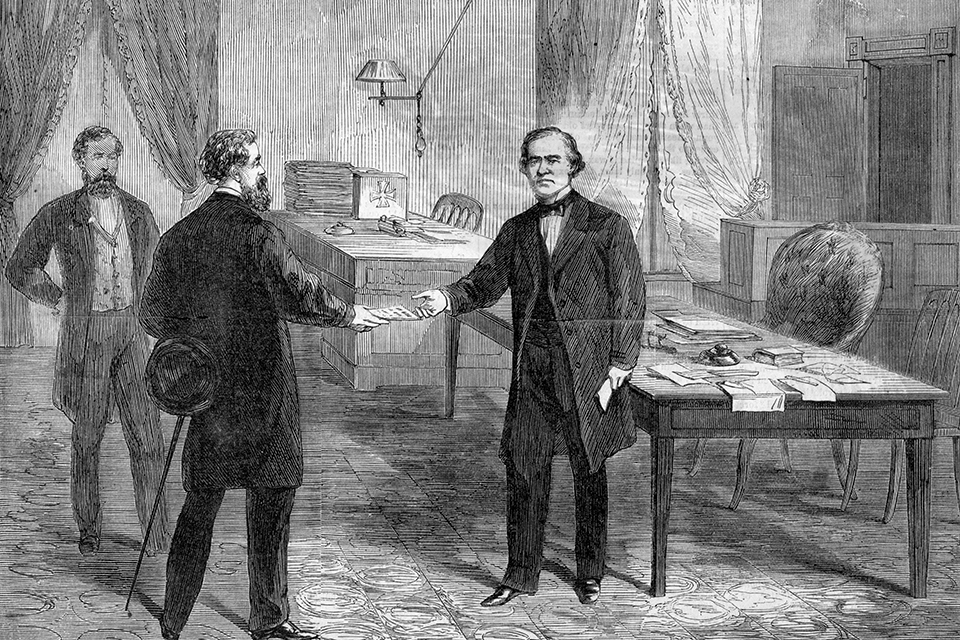

On March 12, 1804, the Senate convicted Pickering by a 19-7 party-line vote. He was removed from office, the first American official to lose his job through impeachment. Partisans of Jefferson wasted no time in moving against Chase. Within an hour of Pickering’s removal, the House impeached Chase by a 73-32 vote.

The articles of impeachment against Chase dealt with four matters the jurist had handled. The most damaging charges focused on the Callender trial and Chase’s instructions to the Baltimore grand jury. During the Callender trial, the House alleged, Chase had displayed “an indecent solicitude…for the conviction of the accused, unbecoming even a public prosecutor, but highly disgraceful to the character of a judge.” As for the Baltimore episode, the House charged, Chase’s instructions to the grand jury had constituted “an intemperate and inflammatory political harangue” that was “peculiarly indecent and unbecoming in a judge of the Supreme Court.”

On February 4, 1805, Chase’s trial began before the Senate, sitting as the High Court of Impeachments. Chase was one of the then six members of the country’s highest court, making his trial a major event. The Senate chamber was “fitted up in a style of appropriate elegance,” a crimson cloth draping each solon’s chair, and an overflow crowd packed the galleries, an observer reported. Presiding was Vice President Aaron Burr, who less than a year before had killed Hamilton in a duel—an irony that did not escape notice. “It was the practice in Courts of Justice to arraign the murderer before the Judge,” the New York Evening Post noted, “but now we behold the Judge arraigned before the murderer.”

A striking figure more than six feet tall with “a repute for eloquence second to few of his day,” Chase, 63, began the proceedings with a lengthy speech impugning the charges against him. His main point was the Federalist creed. “No civil officer of the United States can be impeached, except for some offence for which he may be indicted at law,” Chase said.

Unrepentant, Chase never denied the words and actions attributed to him. The Prospect Before Us was so obviously seditious, he argued, “who is there, that having either seen the book, or heard of it, had not necessarily formed the same opinion?” He claimed his instructions to the Baltimore grand jury had not included “anything that was unusual, improper, or unbecoming in a judge.” He had spoken, Chase said, “as a friend to his country and a firm supporter of the Governments, both of the State of Maryland and of the United States.”

Chase thoroughly wrapped himself in the cloak of free speech. Were he to lose his job because of anything he had said, he argued, “the liberty of speech on national concerns must hereafter depend on the arbitrary will of the House of Representatives and the Senate.” In a nod to humility, Chase asked the senators to make “allowance for the imperfections and frailties incidental to man.”

The Federalists toed their party line. Because Chase had committed no crime, fellow partisans said, he could not be removed. If removal did not require the commission of a crime, argued Chase’s counsel, Federalist Robert Goodloe Harper, removal would be “determined on expediency, and not on fixed principles of law.” Still, Federalists squirmed; they knew Chase had acted badly. Chase’s conduct, Senator William Plumer (F-New Hampshire) confided in his diary, was “a tissue of judiciary tyranny.” Even Chief Justice John Marshall, another Federalist and a colleague of Chase on the High Court, had to admit before the Senate that if Chase’s behavior was “not considered tyrannical, oppressive, and overbearing, I know nothing else that was so.”

Most Jeffersonians maintained their broad view of impeachable offenses. Representative John Randolph (DR-Virginia), who prosecuted the Senate trial on behalf of the House, attacked the “monstrous pretension that an act to be impeachable must be indictable.” All that is needed to make an offense impeachable, said Senator William B. Giles (DR-Virginia), is “for a majority of the House & two thirds of the Senate to agree to that accusation.”

During the 22-day trial, more than three dozen witnesses testified. March 1, 1805, was judgment day. When shortly after noon senators filed into the Senate chamber, the galleries were packed, and anticipation was “wrought up to the highest pitch,” a reporter wrote. Every vote counted; attendants carried in Senator Uriah Tracy (F-Connecticut) on his sickbed. “Hope and fear, according to the wishes of the individual, kept the judgment in suspense,” said an observer. The Democratic-Republicans held 25 Senate seats, the Federalists held nine; 23 votes were needed for the required two-thirds majority.

Burr instructed each senator to “proceed to pronounce distinctly your judgment on each article.” When the votes were tallied, Burr announced the result: “It appears that there is not a Constitutional majority of votes finding Samuel Chase, Esq., guilty on any one article.” The gallery sat in stunned silence, one Federalist senator recalled, “though from their countenance they appeared not only satisfied but highly gratified.”

A majority had voted for removal, but that majority had not met the 23-vote threshold. On the two counts pertaining to the Callender trial, the vote was 18-16 for removal. On the count involving the Baltimore grand jury, the vote was 19-15 to oust Chase. All nine Federalists had voted for acquittal, but enough Democratic-Republicans had broken ranks to swing the result. Prosecutor Randolph was “chagrined & much mortified at the result” and retreated to the House to give “a violent phillippic [sic] against Judge Chase & against the Senate,” Federalist Senator Plumer chortled.

Both Jefferson and Chase learned bitter lessons. Jefferson realized that impeachment was “a bungling way” to recast the judiciary. His party made no further attempts to impeach any judge. Chase learned to control his behavior on the bench and to keep politics out of the courtroom. Time proved Jefferson’s ally in reshaping the bench. During his two terms, he filled 19 judicial vacancies, including three on the Supreme Court.

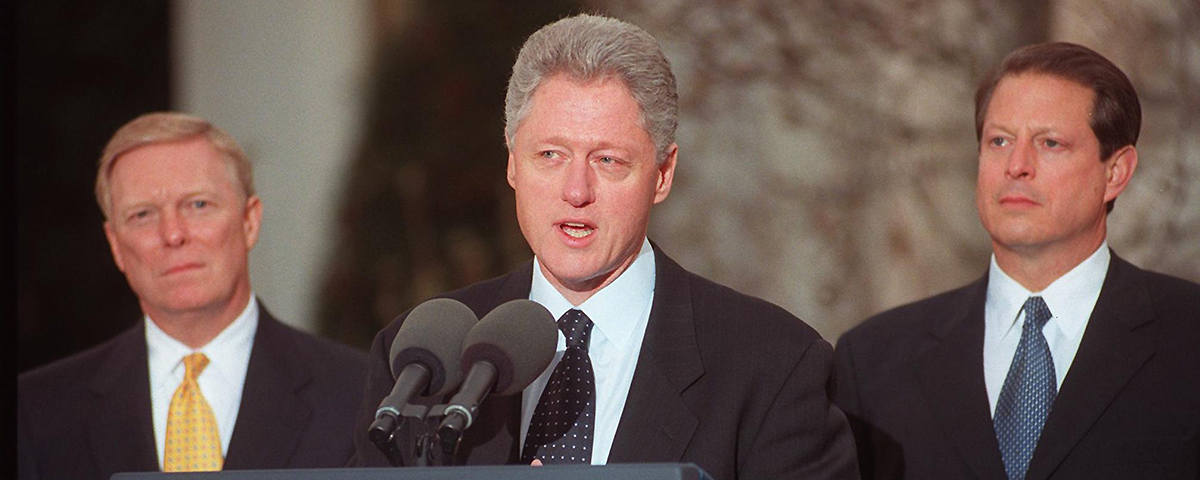

Since 1805, the House has impeached only 16 officials—two presidents, one cabinet secretary, and 13 judges. Of those, the Senate has removed seven and acquitted six, with three resigning before trial. Impeached presidents Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton were acquitted and remained in office. The constitutional requirement of a two-thirds Senate majority for removal is a formidable barrier and has made ouster via impeachment a rare event.

The definitions of “high crime” and “misdemeanor” remain open and elusive. The Pickering case suggests no actual crime is needed, a view many legal scholars embrace. However, targets of impeachment efforts consistently argue to the contrary. The Supreme Court might never resolve the issue, since the Constitution entrusts impeachment and removal solely to Congress. Even if a crime isn’t needed, there are no settled rules as to the specific level of non-criminal misconduct that warrants removal, as the Chase trial shows. The most honest—and perhaps only—answer is, as it has been since the days of Pickering and Chase, that a high crime or misdemeanor is whatever a majority of the House and two-thirds of the Senate say is a high crime or misdemeanor.