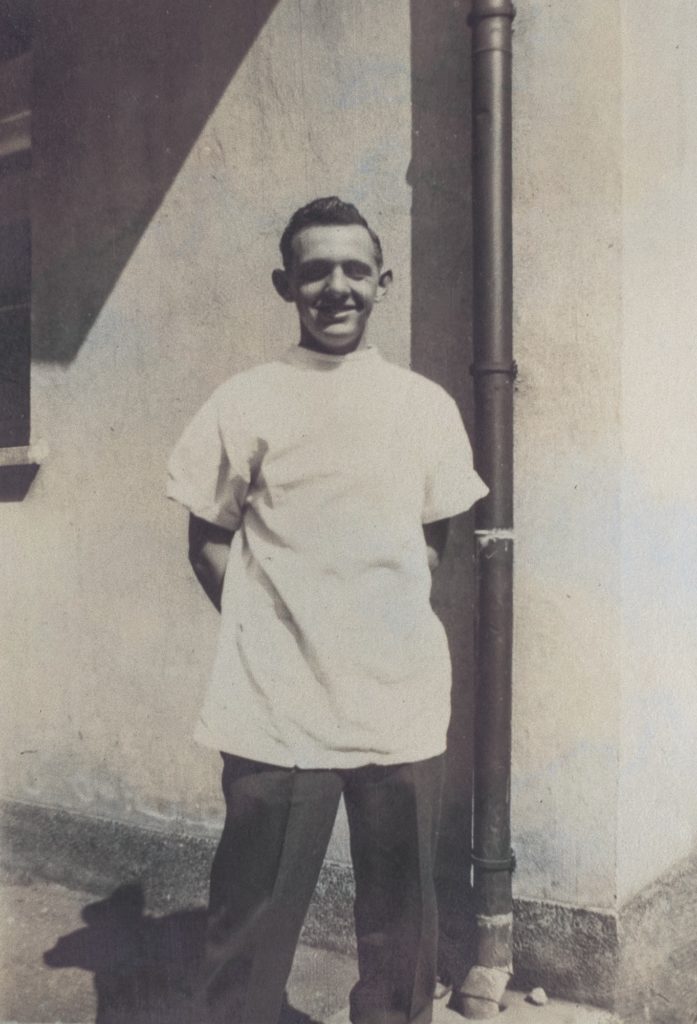

Working in Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison, dental assistant Ed Case got up close and personal with some of World War II’s most infamous figures.

HOW DID IT HAPPEN that an 18-year-old kid from Vallejo, California, found himself at Tokyo’s Sugamo Prison, working inside the mouths of some of the world’s most notorious war criminals? In 1946, just a few months out of high school, Ed Case enlisted in the U.S. Army to take advantage of the G.I. Bill and—because he had worked part-time in a dental lab while in school—landed a job as a dental assistant. Upon reaching Sugamo in January 1947, Case was assigned to the prison wing containing the Class A war criminals—once exalted leaders, now humbled prison inmates facing charges of war crimes, conspiracy to wage war, and crimes against humanity at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

There, Case would become intimately involved in the dental needs of some of the most infamous men in the world, while at the same time gathering their autographs. He collected the signatures of 25 prisoners on slips of paper he handed out, including those of all seven war criminals executed in Tokyo on December 23, 1948. Among them were the likes of General Iwane Matsui and former prime minister Kōki Hirota, who would both be executed for their roles in the Rape of Nanking, as well as General Hideki Tojo, Japan’s wartime prime minister and the man considered to be the archvillain of the Japanese war machine. Case would also be on hand as an American dentist carried out a notorious prank involving Tojo’s dentures before returning home in time for Christmas 1947.

When you reached Japan, how did you land at Sugamo Prison?

There were around 300 of us in a replacement pool. It was about six o’clock in the morning, and there was snow on the ground. The first 50 men they called were assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division, and so on. This went on and on until there were two guys left. Me and one other guy. He was two years into engineering school, and I had worked in a dental lab. We both ended up in Sugamo—he in the engineering platoon that took care of the buildings and me as a dental tech medic.

What were your first impressions?

One of the first things they did when new people arrived at the prison was to take you down and show you the execution chamber. This was done so that you wouldn’t get curious and try to figure out how to get down there on your own. Hanging was the way of execution, and they showed us how it all worked. They had a log [about the same weight as a prisoner] on the end of the noose, and they’d set it on the trapdoor. They’d open the trapdoor to make sure that when the log dropped, the rope didn’t break.

What did you do at the prison?

I spent about a month as a jailer before my job as a dental tech opened up. I worked for Dr. George Foster, who was the prison staff dentist. He was at the prison three days a week and two days at the 361st Station Hospital in downtown Tokyo. They had to have something for me to do when he wasn’t there, so he gave me two hours of instruction on how to be a dental hygienist. Every Tuesday and Thursday I had people come in so I could clean their teeth.

What other dental work went on there?

We had an old field x-ray machine, but the only thing we did on prisoners was pull teeth. We didn’t fill any cavities. The people in charge thought it would be too much trouble to carry on that kind of dentistry. We would have needed a dentist there five days a week. Pulling a tooth was quick and easy. Knowing the prisoners potentially faced execution was probably part of it. No fillings at all? One day a prisoner came in with a toothache. I don’t remember who. The dentist told me to find out which tooth it was so we could pull it, but I told him, “You can’t pull the tooth; he’s got just one little cavity.” He had the most beautiful set of teeth. Everything was straight and perfect. The dentist told me, “If you don’t want it pulled, you fix the cavity.” That was the only time I ever filled a cavity.

Were there any amusing times at Sugamo?

There was one Japanese American soldier there, Dick Koyama, who could speak Japanese. Dick was kind of a character. We had a lot of fun. He was an interpreter-medic combination. When a prisoner went on sick call, Dick could ask him what was wrong. The Japanese had a totally different approach to dealing with medical conditions than we did. Dick would ask a prisoner what the matter was and why he was on sick call, and the guy would recite his whole medical history going back to when he was two years old, and Dick would have to tell him “No. Today.” I thought this was funny.

What was it like for the prisoners at Sugamo?

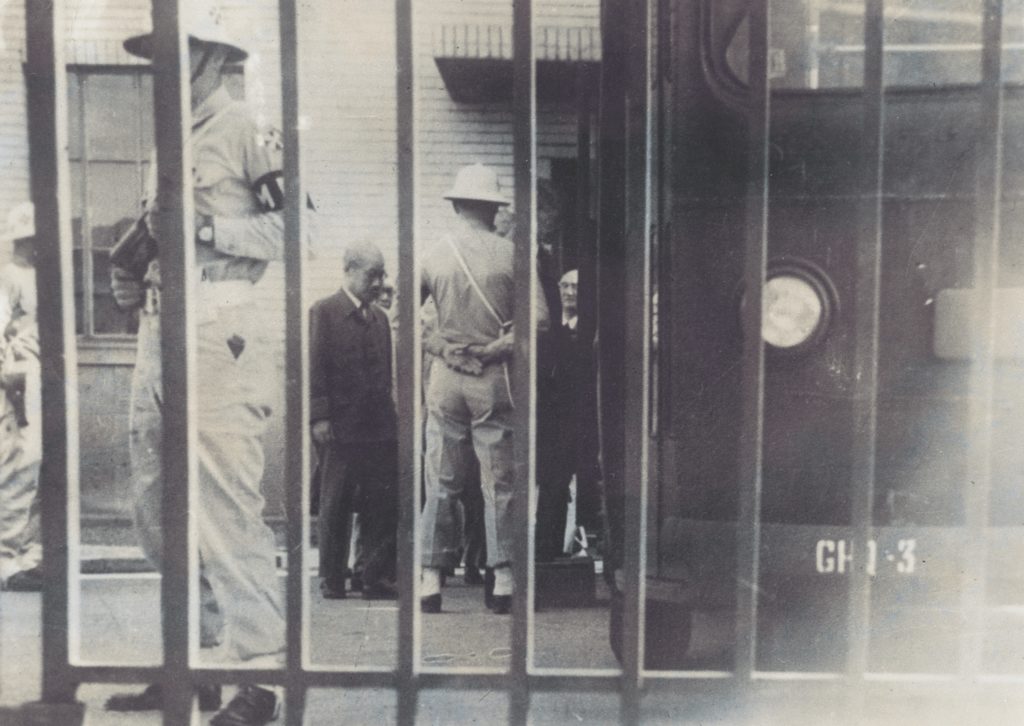

The Class A war criminals in our cellblock got special attention from the guards. My recollection was that the cell doors were kept open. Maybe at night they closed them. A guard had to cross in front of each cell every five minutes to make sure nothing adverse was happening. How they would have committed suicide at that stage, I don’t know. Every day during the week, they’d get on a bus and be taken to [the Ichigaya court building in] downtown Tokyo and put on trial. I’d wonder how the trials were going and what was going to happen to them.

What made you want to collect their autographs?

I don’t know why I took the time to go up there and get signatures from everybody—but I did. I stopped at every cell along the way, asked if they would do it, and they all agreed to sign their names—in Japanese and English both.

How did you get along with them personally?

Some were very open about talking and carrying on a conversation. Those on our wing all spoke quite good English. It was interesting for me to go through that—but an 18-year-old kid doesn’t try to find out what was inside their minds, why they did it, or ask if they’d ever do it again if they had a chance. Tojo was the only one I can remember who didn’t have much interest in carrying on a conversation. He seemed more quiet and unassuming than the rest.

Was there anyone you got to know especially well?

I probably talked to [Foreign Minister Mamoru] Shigemitsu more than any of the others. He really didn’t have anything to do with the war effort, so that’s why they released him quite early [in 1950]. I wanted to know why he was picked to represent the Japanese government at the surrender [on September 2, 1945]. The story was that a six-foot-six Imperial marine wouldn’t have been a good representative of a defeated nation, but Shigemitsu was small; he had a limp and walked with a cane, so that’s why he got the job.

How did you get along with the Japanese people?

When we first arrived, we worried about whether they would be upset about the Americans taking over their country, but never once did I ever run into anything resembling any resentment. They were amazingly friendly. We thought everybody would be really angry, but that was not the case. It was just the opposite. I got invited to homes to have dinner.

What’s the story about Tojo’s dentures?

The prison guards brought Tojo to see us about once a month. When I first saw him, he had recently gotten false teeth. They brought him down for Dr. Foster to work on the dentures. That’s when Foster had the idea to write “Remember Pearl Harbor” on them in Morse code with a dental drill.

What was the reaction?

Nobody knew. I may have seen the dentures, but I never realized that there was anything different about them. Foster told his wife back in the states, and she told a friend, and the word got back to Tokyo. I heard there was talk of a court-martial. He obviously wasn’t supposed to be writing something like that on a denture, so that was the reason behind the court-martial talk. But if they had a court-martial it would have meant exposing a lot more information than the armed forces wanted out, so I’m sure that’s why there was a decision not to court-martial him. I think they were just glad when the whole thing was over.

A 1995 Associated Press story said that it was a U.S. Navy dentist, E. J. Mallory, who carved the phrase.

I remember that it was Foster. Mallory was his buddy. They worked together at the 361st.

How did you find out about it once word got out?

Foster told us what had happened. I heard they brought Tojo down at midnight to look at his dentures so that the words could be scratched out before the colonel and the general found out that they had done it. I was in bed, sleeping. They weren’t about to bring me down at midnight to help with that duty. I wasn’t there, but I knew it happened. The story went around really quick. Once the word starts to spread, it goes fast.

What was your reaction to this?

As an 18-year-old kid, I thought it was kinda neat. Everybody in the dental office laughed when they heard about it. I can remember exactly where I was on December 7, 1941. My dad and I were on the roof of the house, cleaning out the gutters. We had 10 feet to go, and we never finished. Then I ended up in Japan, thinking about “Remember Pearl Harbor.” Crazy how life affects you. ✯

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.