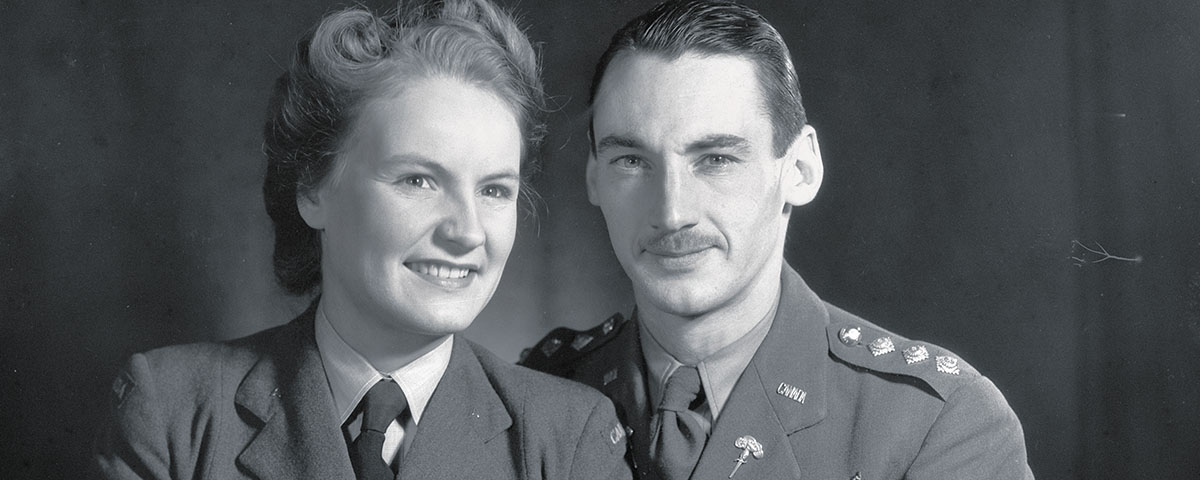

Sonia d’Artois (née Sonia Esmée Florence Butt) was only 20 years old when she parachuted into occupied France on May 28, 1944, just nine days before the D-Day landings in Normandy, to support the resistance as a spy and saboteur. A superior in Britain’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) would later describe her as “utterly fearless.” D’Artois died in Pointe-Claire, Quebec, in 2014 at age 90. This article is adapted from a piece she wrote in 1955 (with Anne Fromer) for Coronet magazine.

MANY THINGS HAPPENED TO ME FOR THE FIRST TIME ON A NIGHT IN APRIL 1944. I rode in a Black Maria; I jumped from a bomber with a tangled parachute; and I began my mission in wartime France as a British secret agent.

“I began my mission in wartime France as a British secret agent. My job was to recruit, arm, and train a secret French force to carry out sabotage and harassment…”

We drove in the Black Maria from Intelligence Headquarters “somewhere in London” to an American airbase equally cryptically located “somewhere in England.” At headquarters the Chief, Colonel Maurice Buckmaster, had told me what my assignment was:

“You will parachute into France with a wireless operator and a demolition specialist. The drop will be 40 miles from Le Mans, where [Field Marshal Erwin] Rommel’s army is concentrated. Your job is, first, to recruit, arm and train a secret French force to carry out sabotage and harassment under code wireless orders you will receive from London Headquarters. Second, you will obtain and transmit to us all possible information on enemy strength, movement, and disposal of personnel and material.”

The chief handed me four large sheets of paper covered with single-spaced typing—it was a complete summary of my mission. It also detailed my cover story.

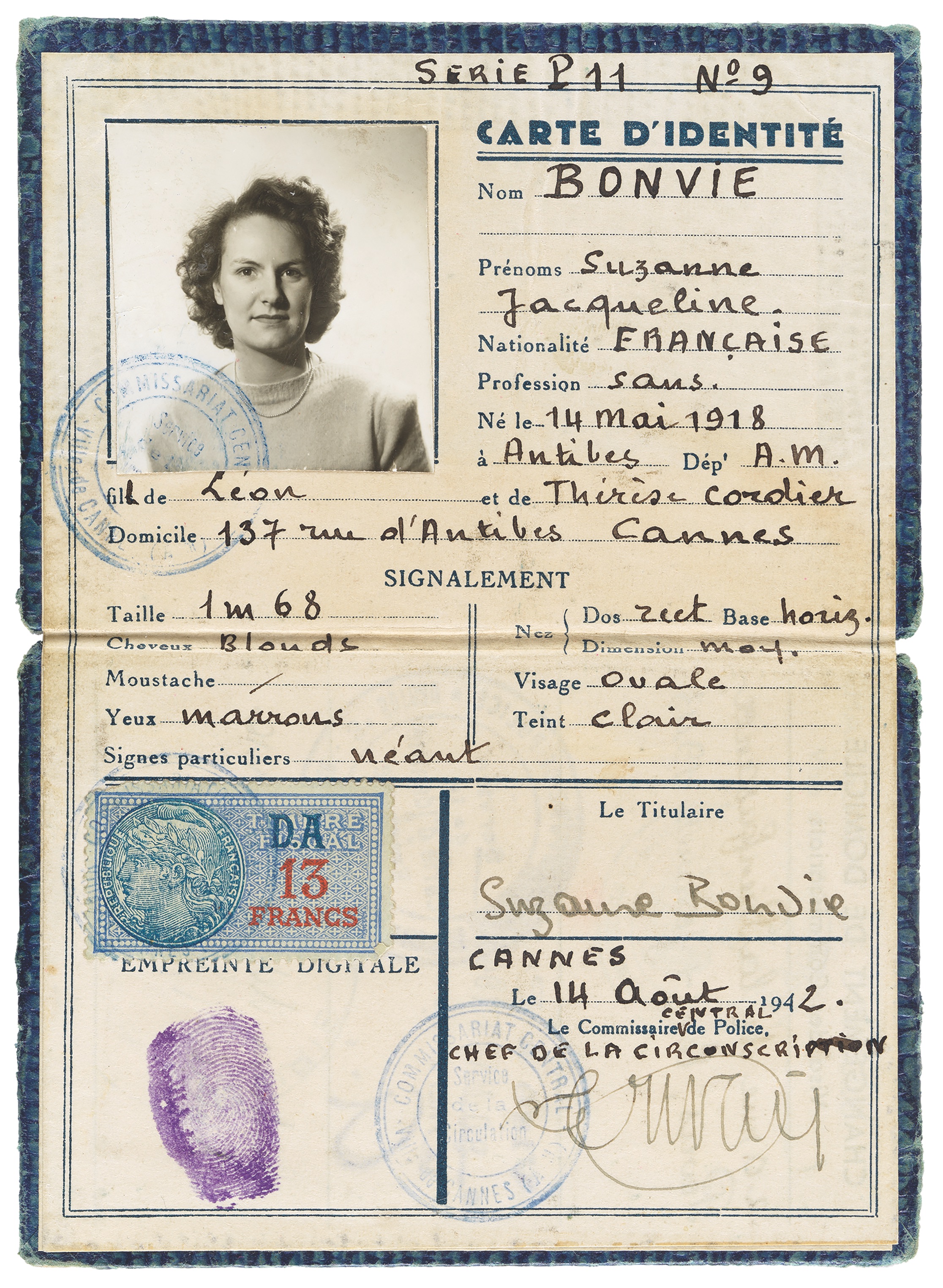

It was a curious experience, to read and memorize the detailed life history of the person I was now to become. It meant adopting not only a new name and identity but a new nationality and personality.

“My name is Suzanne Bonvie. I am the daughter of Alcide and Marie Bonvie, of number ten Rue de Rivière, Bonneville…”

The cover story was careful to pick as my place of residence a small town which had been so thoroughly destroyed by Allied raids that no municipal records remained. The address, which was genuine, was a bombed-out house.

The story took my personal history back to grandfathers and grandmothers, aunts and uncles. There were, purposely, little inconsistencies in it since a perfectly consistent story would be more likely to arouse suspicion.

“I am now going,” my cover story stated, “to stay with my cousin Jean-Paul Bonvie, who has a château near Le Mans…”

There was a man named Bonvie who had a small château near Le Mans, and that was my destination. Bonvie was of the Maquis.

The chief opened a drawer of his desk and took out a small Glassine envelope containing some white tablets and a single blue capsule. He handed it to me and said in an even voice:

“The white—remember, the white are stimulants. Take one if you ever need a last extra ounce of endurance to pull you through an emergency. The blue…well, if you are captured and at your last extremity—it will work in three minutes.”

His words were a grim reminder of what could be the climax of the six strange months I had just spent.

It had all started when I was summoned to an interview in a dingy London hotel, given a casual but thorough examination in French and my knowledge of the French people, assigned to the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and hustled off to an isolated country house in Surrey for training.

The FANY, of course, was only a cover for the real purpose of my enlistment—to become a spy, an intelligence agent, an underground organizer behind the German lines—a member of a secret third front which was to pin down and harass the German defenders against the invasion of Europe.

My fellow agents at the Surrey country house where we trained were English who, like myself, had been educated in France; citizens of Mauritius, a French-speaking English colony; South Africans who had lived in Madagascar; and some French-Canadians.

We spoke nothing but French. But more, we had to live French. We were watched every moment. Did we instinctively place our knives and forks in the French position after eating? Parties were held—for the sole purpose of getting us a little drunk. Did we lapse into English? Did we talk too much?

One night after such a party I awoke to find an officer sitting at my bedside. I sat up indignantly.

“Quite all right,” I was told stiffly, “we were only ascertaining if you talk in your sleep—and if so, in what language.”

Candidate agents had to learn how to recognize one person in a crowd solely from a description, be able to appraise a person’s character and sincerity almost at sight, after a short talk with him.

“You’re going to have to choose people to work with,” we were told, “people who might be planted by the enemy, people whom the enemy could later bribe. One mistake might literally mean death.”

We had to learn how to steal…from another student’s quarters, from a locked and guarded room. We had to be able to remove one sheet of paper from a drawer full of documents and leave the other contents undisturbed.

In what we called the “Cooking School” we learned how to combine ingredients obtainable at any corner store into deadly explosives.

All that was a preliminary to the toughening school in Scotland. The object of this second school, they told us, was to condition our bodies to withstand fatigue. It nearly killed me.

The few feminine agents were treated exactly the same as men, on the reasonable grounds that we would be living, working and fighting under the same conditions—and against the same enemy. The constant watch, the penetrating appraisal of us, was carried until the very end when I was told to report to London for further orders.

At briefing headquarters the chief greeted me with one word: “Good!” Three days later he summoned me again. That night he rode with me in the Black Maria out to the airport.

The plane banked to the left—the signal that we were over the “drop.” As I looked out on the moonlit mass of France, I was horribly afraid. Yet it was a relief.

I moved to the hatch in the belly of the plane. Behind me crouched my wireless operator, a young Englishman who had recently acquired the incongruous name of Alexandre Dumont, and a wiry, middle-aged, genuinely French Maquis I knew only as Paul.

The light on a panel facing the hatch glowed red—“ready.” When it turned green, that was “go.” From my half-crouched jump position I watched that light. It stayed red for an eternity of 10 seconds. Then it was green.

A huge paper bag popped in my ears and a giant slapped me between the shoulders. Then everything was still and silent; even the sound of the plane’s engines, already incredibly distant, was only something rhythmic blending with the silence.

But I had bungled my jump. After four perfect practice drops I had failed when the real thing came, and I was impotently furious at myself. Endlessly our parachute instructor had repeated: “Hold your head up when you go through the hatch, otherwise you’ll turn ears over bottom and twist your shroud lines.” I had done just that. I had found it impossible not to look down.

According to everything I had rehearsed, I should now be floating gently to earth, manipulating the shroud lines to guide the chute toward a friendly ring of dimmed signal lights on the ground. Instead I was dropping out of control and much too fast. I could see no lights. I didn’t even know which way the earth was. Worst of all, in tumbling helplessly through the air I had lost my grip on the precious bundle of French clothes which British Intelligence had gone to so much trouble to collect for my French mission.

I struggled with the lines for another 10 futile seconds before the earth came up and hit me. I blacked out.

When I came to, there was a rumbling noise in my ears. I got my breath back, collected my senses, but the noise remained. It was low, insistent, and not too distant.

My instinct was to move in the opposite direction. In enemy territory so continuous a sound was not likely to be made by friends.

A grove of trees to the left offered cover. I got up and discovered that I was still firmly attached to my parachute. “Bury your parachute immediately” was the “A” of our alphabet. I tugged furiously at the release. Nothing came loose. I must somehow have fouled it in my bungled drop.

I pulled my Colt automatic out of my pocket and started toward the trees, dragging the chute. It seemed to take hours of hard work, like walking in a plowed field up a steep grade, before I reached the leafy shadows.

I could still hear that ominous rumble off to the right. Once it stopped for a moment, to the accompaniment of much screeching, then started again. I guessed that it was a line of trucks on a road, running blacked-out and brought to a sudden halt.

I stopped under the first tree and called as loudly as I dared: “André.” That was the code name of the man who was to meet me if all went well.

There was no answer, but something stirred in the shadows and presently I could make out the shape of a man, watching me. Then another figure took shape, and another…until there were eight.

I gripped my pistol tighter. I had to decide quickly whether to speak again—or shoot. Then, with blessed relief, I heard a voice say in French: “It is a woman!”

The men came closer, and I could see that they were quite elderly and roughly dressed.

“André is dead…the Boche got him three days ago.” This revelation of the violent death of the man who was to have been my chief helper and adviser made me realize, as nothing else could, that I was now among people by whom sudden death was accepted as a way of life.

I explained to the Maquis who seemed to be the leader of the group—the only man who had spoken until then—that two men had parachuted with me, that the pack containing my clothes had dropped after me, and that we must search for the men and the bundle.

He shook his head and jerked his thumb toward the rumbling noise which continued ceaselessly.

“There is a big Boche convoy moving tonight,” he said. He pointed to one of the shadowy figures about him. “Pierre here has just told us that he watched the convoy from behind a hedge and saw it stop to pick up a pack. We knew it belonged to one of you who had jumped. As for those who came with you, there are others to meet them.”

That was the most blood-chilling news of a night of misadventure. The enemy would now know not only that an agent had been dropped in the area, but that it was a woman—and a woman whose general description could be pieced together from the size of the clothing in the pack.

“We must hurry,” said the Maquis leader.

We moved through the wood, away from the rumbling trucks. Out in the open moonlight I saw that my companions were even older than they had seemed in the shadows.

As if in answer to my thought, their spokesman, whose name was Alain, said: “We old ones meet and guide those who come in planes. The younger men are needed for more serious work.”

All night we walked through fields, but when dawn came we took to the road. “We” were only three now. The rest of the men had melted away, one by one, in the night. A party of nine traveling together would be sure to arouse suspicion.

It seemed a curious reversal, to hide by night and to walk openly by day, but Alain explained that there was a curfew in the area and that anyone found out at night would be arrested. On the other hand, to attempt concealment by traveling through fields in daylight would be equally suspicious.

But it took a real effort for me to try to walk along that French road as though I belonged there, a road that soon would be crawling with enemy trucks, perhaps marching soldiers who would pass close enough to touch.

The sun rose and it became unbearably hot. The clothes I was wearing when I jumped—all the clothes I now owned—consisted of sweater, divided skirt, and ski boots.

Underneath, next to my skin, I wore a money belt containing a million francs. It had had a comforting feeling when first I strapped it on—a million francs in genuine smuggled French banknotes, but now it was an intolerable burden in the heat.

For 30 hours we walked without sleep, with scarcely a pause to rest and eat. Thus it was at dawn that we arrived at the Château Bonvie. My English wireless operator and Paul, the explosives expert, were already there and greeted me like a long-lost friend. So did my “cousin” Bonvie, who turned out to be very young, not more than a year or two older than I.

“We have been expecting help so long and need it so badly,” he said. “Organization, training, weapons…we have had none—since the last group was wiped out, and that was almost a year ago.”

“Yes,” I said, “we will start work tomorrow.”

Next morning began the strange double life I was to lead for the next five months, lives so different from the rational existence I had led for 18 years, so kaleidoscopic in incident, adventure, and danger, that sometimes now it is difficult to believe that they really existed at all. Bonvie took me into Le Mans to introduce me to contacts; to the safe houses where I could obtain information, make contacts, or seek refuge in an emergency.

The streets swarmed with German soldiers. They crowded the stores, the restaurants, the hotels. The townsfolk were in evidence, too, going silently about their business affairs. Walking casually among the teeming German uniforms with Bonvie, I was aware that not one among them would have hesitated to shoot me down on the spot if they had known who I was.

We entered a number of little shops on side streets to be greeted, after Bonvie’s introduction, with a sort of guarded warmth.

In each shop I made a purchase. This served two purposes; first, to accustom me to the actual use of the Occupation ration books, which in training school I had studied as carefully as a textbook; second, to avoid suspicion if we were being followed, as conversation not accompanied by a business transaction might well have aroused something more than curiosity. The ration books I carried were expert forgeries of the real thing, printed in England, along with my identification papers from authentic originals stolen and smuggled out of France.

By day I belonged in the “lower town,” making contacts among the men of the district who had been demobilized after the fall of France and were restless for action; among the refugees who had fled from farther north with the invasion and could not go back…or had no home, no village, no town to return to because Allied air raids had wiped them out. It was as dangerous as handling dynamite, this business of recruiting an army under the very noses of the conquerors. One error of judgment, letting a traitor into our ranks, could—and probably would—mean torture and death to everyone in my group, and to their families.

By night I disappeared from the haunts of honest Frenchmen into the shadowy quarter of black-market cafes and bistros patronized almost entirely by Rommel’s officers and collaborators—male and female. Soon I was accepted by the German officers—and, equally important, by the even more suspicious and calculating French collaborators and “officers’ girls.”

One German colonel in particular took to stopping at my table to exchange a few words, then to sitting with me over aperitifs.

From him and from other contacts I drew my information for transmission over my wireless frequency to headquarters in London. Here it was fitted into the intricate mosaic of intelligence contributed by other agents, which was then transmitted to Supreme Allied Headquarters.

Then, one evening, a strange mishap occurred. For a moment I was certain that it meant the end of my mission and myself.

The colonel sat down at my table, and I shifted my chair to make room for him. My handbag—in which I carried my revolver—slipped off the back of the chair and fell to the floor with an ominously audible clank.

For an instant I felt terror. It must have communicated itself to him, because the cold penetrating gaze he turned on me left no doubt he knew what my bag contained.

I reached for the bag and, as casually as I could, opened it. But what I took out was not the revolver. It was my forged permit to carry a gun and it was signed by Gestapo headquarters.

I pushed it across the table, left it in front of him for a moment, then returned it to my purse. I managed a faint smile that I was far from feeling.

From that moment the colonel and I understood each other. I was a Gestapo spy, probably the mistress of a high Gestapo officer, which accounted to him for a lot of things—why I frequented the expensive black-market cafes, why I never let him accompany me to my quarters. I was a dangerous person, but that lent spice to our tête-à-têtes. He was playing with fire, he let me know in so many words—but he liked it.

The colonel, whom I could easily visualize as one of those interrogating officers, became my most valuable informant.

One day he gave me the ominous information that for weeks now the Abwehr had been looking for a British woman agent who had been parachuted into the area. Her clothes had been found, some other clues had been unearthed, and the Abwehr expected to have her in their hands soon. “Very soon, in fact,” he added grimly.

“That is one thing I could never bring myself to do,” I said “—drop in a parachute….” And the shudder which accompanied this comment was very real.

IT NOW BECAME MORE URGENT THAN EVER TO RAISE OUR MAQUIS FORCE to required strength. I turned for aid to an influential parish priest in Le Mans, Father LeBlanc. Thereafter, Father LeBlanc’s influence with his parishioners became our potent ally. Before long we had our “force” of 500 staunch Frenchmen, incredibly brave, utterly reckless when they got an opportunity to deal a hurtful blow against the invaders. They were divided into three groups, with widely scattered rendezvous.

Our arms and ammunition came from the skies. In answer to our requests, we would receive code messages giving the time and place of a parachute drop. Our favored method would be to round up the supplies, bury them, and wait for market day, when there was least risk in moving them. The enemy never knew that many of the innocent carts slowly trundling their way to market were loaded, under the turnips or hay, with Bren and Sten guns and long black boxes of cartridges.

Now we were able to launch a minor reign of terror in the very heart of Rommel’s area. We cut his communication lines as often as they were repaired. We blew up his petrol tanks. We kept the German maintenance crews busy with emery powder in diesel electric generators; we ambushed convoys, lying silently behind hedges and leaping out behind a blast of gunfire.

For these jobs we traveled miles into the lonely countryside, not only to minimize the danger of German reinforcements being rushed to the ambush but to avoid the brutal reprisals.

Then it came…the message we had waited for—the message which was, in the final analysis, the reason for our being there. None of us knew, of course, when the invasion was to come.

Our special instructions were only that we were to listen to the BBC without fail on the first and 15th of every month.

As soon as a prearranged alert came, each agent was to act on nightly preparatory commands aimed at deploying our forces for the crucial, coordinated strike on D-Day eve.

It came on the night of June 5, 1944. That midnight in full force we followed our blueprint….blow up the turntables in the Le Mans railway yards…cut every telephone wire leading out of the city. Blow up all possible road and rail bridges.

Never had my Maquis been so bold, so ruthless, so reckless. What they had scarcely dared hope for during four years of soul-deadening defeat had come true. They were like men possessed—possessed by an unholy joy. So reckless had they been, in fact, that we thought it wise to suspend all operations for a day or two.

On the night we were to reassemble I walked through the forest toward our meeting place. Suddenly a hand was laid on my arm and a voice whispered, “It is Jean. Do not speak.”

I walked beside Jean, knowing something terrible had happened. Not until we had gone more than a mile—away from the rendezvous—did he speak, and then there was agony in his voice.

“They came,” he said. “The Abwehr. As we were eating. They surrounded the place, at least 200 of them. We got a warning from the lookouts, but as soon as they shouted, the Boche opened fire. We fired back as we ran. How many broke out, and how many were killed and captured, I do not know.”

We made our way in grim silence to the emergency rendezvous. A handful of men were there. I was glad to see that Paul, our dependable, resourceful group leader, was among them. He tried to be optimistic.

“It will be hours before we know how many are lost,” he said. “Many will make wide detours, and many will be waiting hidden in the woods to warn you….”

By dawn 80 men had stumbled into the hidden clearing, some wounded, some exhausted. One man I kept watching for did not come. He was the wireless operator—by far the most important single person in the group. I questioned each man as he arrived. One of the last to come in told me: “Dumont is dead. He was sitting beside me.”

Without Dumont we were no longer an organized action group. There could be no more contact with headquarters in London. His death made us guerrillas.

In the afternoon one of the men who had escaped the raid came in with the bitter details that he had gathered in the town.

Few of our men had salvaged their guns. We had practically no ammunition. By now the Abwehr would know the names of everyone in the group, so that none could enter Le Mans. Worse, because we were out of touch with headquarters, there could be no more droppings of guns and ammunition.

There remained only one course of action open to us…to do as much damage as we could before the inevitable closed in.

OUR LAST PROPOSED OPERATION ASSUMED DOUBLE IMPORTANCE—the blowing up of a munitions train bringing guns and ammunition to Rommel. There would have to be a change in plans, for we would now have to disable the engine and capture precious supplies intact before setting the train afire.

Never had we planned an operation more carefully, or measured out demolition charges so precisely.

We could see the smoke of the engine far off as we lay flattened along the top of the embankment.

The train approached with maddening deliberation, seemed to hang poised over the detonator…then, in slow motion, the engine toppled on its side and dragged with it three or four freight cars.

Instantly all was confusion.

Hissing white steam enveloped the engine. Guards screamed as they jumped from the overturned cars. From the embankment came the crash of rifle volleys. Here and there I could see the train’s guards drop and lie still by the tracks. Others returned our fire wildly. Groups of Maquis moved in on the crippled train, guns blazing. Soon came the signal—all resistance ended.

Speed had been the essential ingredient of the operation, and now it was even more necessary. In a few minutes—when the train failed to confirm its arrival at the next signal point—retribution would be on its way. We worked against time to locate and unload the small, light, and efficient German utility guns of the tommy-gun variety; these we would use in running battles with the Wehrmacht.

Those who had lost their guns in the raid rearmed themselves immediately and stuffed their pockets full of cartridges. We formed lines to carry guns and ammunition to waiting trucks.

Finally we laid short-fused demolition charges under the railway wagons. Then we scattered, to travel fast but by wide detours to the new rendezvous.

We were still in sight of the train when the first charge went off with a force that nearly lifted us off our feet. When we were miles away, we could still hear muffled explosions as the train methodically blew itself to pieces.

In the frenzied days that followed, many of our gallant men died in forays, in ambushes, in attacks on the flanks of enemy columns moving against the invasion. Then one day a patrol brought back tremendous news. They had contacted a patrol from General [George] Patton’s army. Conducted to an advance post they had asked what action would best fit in with the Americans’ plan of campaign around Le Mans.

“Airports,” they were told. “Tackle any airports in your district. Those Heinkel dive-bombers have been giving us hell!”

Three planes had crashed to earth before the airport’s defenders, a regiment of Luftwaffe troops, were alerted. Although they greatly outnumbered the Maquis, we had one tremendous advantage—cover. Every time they tried to cross the airport and get within striking distance of us, we pinned them down with rapid fire.

Until midafternoon we contained the Luftwaffe regiment. Then it came—the sound of heavy gunfire from the direction of Le Mans. By nightfall General Patton’s forces had the airfield surrounded.

WITH MY IDENTITY ESTABLISHED, THE AMERICANS ASSIGNED ME TO INTELLIGENCE COORDINATION…questioning prisoners. Then came the strangest experience in that final phase of my military career.

One day I was assigned a prisoner who had proved exceptionally stubborn under preliminary questioning by American Intelligence officers. They were turning him over to me in hopes that I might be able to break down his adamant silence.

I glanced at the name on the briefing sheet. It was my colonel of the bistros.

He marched in with his head in the air, stood before my desk, saluted automatically, and looked at me for the first time. His eyes stared from their sockets. His face turned crimson. “You!” he gasped. “You!”

As I motioned him to the chair before my desk, I could almost see the thoughts whirling through his brain…amazement, disbelief, self-reproach, then finally a grudging respect. He shrugged and sat down. A grim half smile flickered on his lips.

“What is it you would like to know—that I have not already told you?” he asked. There was bitterness in his tone, but also a slight note of mockery in his voice, almost of banter.

“Oh, there are a few gaps,” I answered.

This article appears in the Autumn 2018 issue (Vol. 31, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: I, Spy