[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen the secession crisis evolved into civil war in the spring of 1861, most of the men in the U.S. Army’s officer ranks had one thought: Get home and serve the government of their allegiance. Southerners posted in the Far West—principally California and the Washington and New Mexico territories—faced the greatest obstacles. Complications included the six weeks or more of lag between events in the East and news of them in the Far West. Army officers were pulled in two directions. On one hand, their home states issued “proclamations” upon secession inviting native sons to come home. On the other, General-in-Chief Winfield Scott, a Virginian, ordered all officers to “take and subscribe anew the oath of allegiance to the United States of America.” For many, that decided it.

If they decided to resign, they had to determine the best way home, not knowing if they would be charged as traitors en route. Even resigning their commissions was complicated. Technically, they remained members of the U.S. Army until their resignations were accepted, which, given the slow pace of communications and bureaucratic inertia could take months. And there was no guarantee they would not be arrested for treason. Some simply turned in their resignation, took off their uniform, and left.

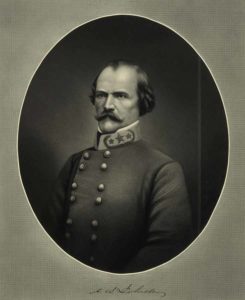

The most famous name in the pre–Civil War Army to side with the Confederacy was Albert Sidney Johnston, the army’s second-highest ranking officer (after Samuel Cooper, who also went south). In 1861 Johnston commanded the Department of the Pacific with headquarters in San Francisco. Though a Southerner who considered Texas his home state, he was committed to honor his oath to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies. He assured California Governor John G. Downey that before he resigned, “I shall give due notice and turn over intact my Department to my successor.” His sense of honor would permit him to do no less, unlike David Twiggs facing the same dilemma in Texas after replacing Robert E. Lee as commander of the department.

On April 9 Johnston received word that Texas had seceded. His path now seemed clear; he could not take up arms against the people of Texas any more than Lee could against the people of Virginia. That same day, he sent his letter of resignation to President Abraham Lincoln (via the War Department). His sister-in-law tried appealing to his patriotism, saying, “My love for my country is such that I care not who rules for four years; we must all unite now in guarding its honor and preserving our beloved Flag.” Her words failed to persuade.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“My love for my country is such that I care not who rules for four years; we must all unite now in guarding its honor and preserving our beloved Flag.”[/quote]

Unwilling to trust Johnston’s sense of honor, Scott sent Brig. Gen. Edwin V. Sumner to relieve him. Sumner reached San Francisco at April’s end and Johnston turned over his command as promised. Meanwhile, other officers in Washington, D.C., considered Johnston’s resignation a catastrophe and tried to get the government to hold off accepting it. Assistant Adjutant General Irvin McDowell wrote, “He is the only man to save us next to General Scott, and if we lose him, God only knows what a calamity it will be to our country.” But the die was cast, and on May 6 Scott accepted Johnston’s resignation, presumably with Lincoln’s blessing.

Initially, Johnston resolved not to fight for either side, but he found he could not remain on the sidelines. Recalling his role in Texas’ War of Independence, he remarked, “Texas has made me a Rebel twice.” When word of his new allegiance reached Washington, Secretary of War Simon Cameron on June 3 ordered his arrest.

Unaware he was now deemed a traitor, Johnston planned to report to the new Confederate government in Richmond. Although he set out to sail around the Cape Horn to New York before making his way south, friends advised him that he would be recognized and arrested—he instead traveled overland with a group of like-minded Southerners. On June 16 they left Los Angeles to undertake the 800-mile journey to Texas in the heat of summer.

When the 59-year-old Johnston reached El Paso, he took a stage coach to San Antonio, and then to Houston, where he learned the Federal blockade made it unsafe to continue his journey by ship. He proceeded by road again, crossing the Sabine River and reaching New Orleans in early September. At this point, Albert Johnston was the “golden boy” of the Confederacy in Texas and Richmond.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ther Southern bluebloods to be stranded in the West were Major Lewis Armistead of North Carolina and Captain Richard B. Garnett of Virginia, both of the 6th U.S. Infantry in California. Both resigned as soon as they learned of their home states’ secession, Garnett on May 17 and Armistead on May 26. Some time passed before they left, however. In the end they joined Johnston. In the month before they departed they were in the awkward position of having resigned yet daily interacting with loyal brother officers.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]In the month before they departed they were in the awkward position of having resigned yet daily interacting with loyal brother officers.[/quote]

On June 15 they were part of one of the most remarkable farewell parties in American history, given by Captain Winfield Scott Hancock and his wife in Los Angeles. It was a melancholy affair, with the bizarre spectacle of men who were “going South” embracing loyal U.S. Army officers—tears flowed freely. Mrs. Hancock would describe it as a “never-to-be-forgotten evening.” The tears were not just over having to choose sides in the great national conflict, but the next time they met might well be in battle trying to kill each other. Armistead summed up their feelings in his emotional goodbye to his long-time friend Hancock: “You can never know what this has cost me.” He took off his United States uniform for the last time and slipped out of town that same night. (Famously, the next time Armistead and Hancock met they were on opposing sides at Gettysburg on July 3, 1863.) Richard Garnett found it even harder to turn his back on the country that he had sworn to defend. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy in 1841, he spent 20 years in the Army. He attended the farewell party in his uniform but remained in the background that evening. He and Armistead both made the journey home as civilians. The next uniforms they donned were Confederate.

Both Armistead and Garnett were warmly welcomed into Confederate ranks. Armistead was appointed an infantry major in the Confederate Regular Army, and four months later promoted to colonel in the Provisional Confederate Army. Richmond appointed Garnett an artillery major in the Confederate Regular Army, and six months later brigadier general in the Provisional Army. Both ended up in George Pickett’s Division at Gettysburg, commanding two of the three brigades during Pickett’s Charge on July 3, 1863—Garnett would be killed that day, and Armistead mortally wounded.

Their Gettysburg division commander had also been on the West Coast when the war began. A captain in the 9th U.S. Infantry, Virginia-born George Pickett was in the same allegiance dilemma during the 1861 secession crisis. At the time he was posted on Bellingham Bay in Washington Territory. He personally opposed disunion and held his oath of allegiance as an officer sacred, but those feelings took a back seat to his loyalty to Virginia. It is not clear when he got the word that his home state had seceded on April 17, but he resigned June 25. In February 1861, he had expressed his feelings to a friend, Major Benjamin Alvord at Fort Vancouver: “I do not like to be bullied nor dragged out of the union by the precipatory and indecent haste of South Carolina [which seceded in December], but,” he went on, “we [Virginians] ask but our rights and no more [and] they are ignominiously rejected.” His resignation was accepted by his department commander, Colonel George Wright, within the next six weeks, so he felt free to head home.

Pickett’s delayed arrival to the East had missed more than just the launch of the Confederate States of America; he had also missed the first big battle of the war at Manassas, Va. According to wife Sallie Pickett, his “unavoidable delay” in reporting would be criticized “most cruelly and severely” by friends and family who felt he had dithered too long. Still, the nascent Confederacy needed every experienced soldier it could get, so he was appointed a captain of infantry in the Provisional Army. This was a relatively humble appointment for a West Point–trained officer and veteran of the Mexican War, and may have been a direct result of his late reporting. Whatever the reason, Captain Pickett of the U.S. Army started his service to his new country as Captain Pickett of the CSA Army, while other former U.S. Army captains, such as Pickett’s friend James Longstreet, were promptly commissioned colonels or higher.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]ther Southerners stranded out West managed to get home with less hardship and drama than Johnston or Pickett. Dabney H. Maury, a fellow Virginian and West Point classmate of George Pickett’s, was assistant adjutant general for New Mexico Territory, stationed at Santa Fe, when he got word of his home state’s secession. He and other officers had anxiously awaited the arrival of every military dispatch trying to keep up with the news. He submitted his resignation in May and received his separation notice from the War Department on June 25. He made his way overland to Richmond, arriving in mid-July, and was promptly commissioned by both Virginia and the Confederacy (Colonel by Virginia, Lieutenant Colonel by the Provisional Army). His first posting was on General Joseph E. Johnston’s staff at First Manassas.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]“I do not like to be bullied nor dragged out of the union by the precipatory and indecent haste of South Carolina, but, we ask but our rights and no more”[/quote]

Florida resident William W. Loring and Louisiana-born Henry Hopkins Sibley were both posted in New Mexico in the spring of 1861. Loring, a colonel, had inherited department command in March when the aged Colonel Thomas Fauntleroy tendered his resignation and went home to Virginia to offer his services to the Confederacy. Loring had written a letter to the governor of Florida on February 14 saying, “I shall always hold myself ready to serve my State and the South should the time come when my services will be useful to them.” Now he assembled his officers at Santa Fe and informed them he intended to “join the Southern Army, and each of you can do as you think best.” Since he wasn’t a West Point graduate, he did not have that guilt nagging his conscience. He resigned on May 13 but stayed around 31 days to turn over his command to Colonel Edward Richard Sprigg Canby before leaving. Reaching San Antonio, he wired Confederate Secretary of War Leroy Pope Walker in Richmond, “I am now hastening to the scene of the war, fearing that my application both through officers who have resigned and also by letter, may not have reached you. I again offer my services and shall leave here tomorrow via New Orleans for Richmond.” The Confederacy welcomed Loring with a colonel’s commission in the Regular Confederate infantry to date from March 16, which was about the same date he had taken over command of the Department of New Mexico.

Loring’s comrade-in-arms and fellow secessionist in New Mexico, Major Henry Hopkins Sibley, resigned on April 28, asking for “the authority to leave this Dept. immediately.” He had already approved the resignations of several subordinates, adding the endorsement, “[N]o objection can be raised against its acceptance.” For himself, he was off to fight under “the glorious banner of the Confederate States of America.”

He sent his letter of resignation not to the War Department but to his department commander, who just happened to be Loring. While he waited to be relieved of command, he continued to go about his duties. He was made more impatient to leave by the rumors circulating in the territory of the availability of high-ranking commissions in the Confederate Army. Having heard nothing by May 31, he took seven days’ leave of absence, bid his command goodbye, and left Fort Union on the next stage. He had secretly cooked up a scheme with Loring, urging the department commander to turn over all federal military stores to Confederates next door in Texas. Instead Loring handed off his command honorably and left Santa Fe with the well wishes of his former comrades-in-arms, who commended his “unflinching honor and integrity.”

Loring met up with Sibley in El Paso, and together they traveled through Texas as civilians. Sibley’s dreams of high command were borne out when he reached Richmond and Jefferson Davis appointed him a lieutenant colonel of cavalry in the Regular Confederate Army, to date from March 16.

The stampede for the exits in New Mexico Territory in the first half of 1861 was truly remarkable. Besides Fauntleroy, Maury, Loring, and Sibley, Southerners resigning and leaving included Lieutenants Joseph Wheeler, James Longstreet, and George B. Crittenden. One could have officered a respectable army with all the Southerners who resigned. To some Unionists, their sheer numbers and in a few cases open plotting were proof of a vast conspiracy to deliver New Mexico to the Confederates. David Twiggs’ example next door in Texas was the template for how to do it, and Henry Sibley for one was ready to pull a “Twiggs” if only he could have gotten a few more conspirators to join him. He later admitted that it was only “sickly sentimentality” that kept him from acting more decisively. It was no coincidence that Texan John R. Baylor had an invasion army massed on the border even before the First Battle of Bull Run and proceeded to proclaim himself military governor of the region.

Georgia-born Captain Lafayette McLaws, Jefferson Davis’ cousin-in-law, faced no crisis of conscience in the winter of 1860. He wrote his wife on December 17 from New Mexico while campaigning against the Navajo Indians that if Georgia seceded, “My present idea is to go with my State as a matter of course. To offer my services as a military man.” He learned of Georgia’s secession on January 16, 1861. His superior, Colonel Canby, granted him a six-month leave of absence to go home, and he turned over all of his government property four days later, demanding a receipt for the same. Only then did he set out for home.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]”I shall always hold myself ready to serve my State and the South should the time come when my services will be useful to them.”[/quote]

Still in uniform, he traveled from Albuquerque to El Paso to Fort Davis, Texas. There he caught a stage to Jefferson City, Mo., and then on to Lexington, Ky. Meanwhile, his brother William R. McLaws was working to secure him an appointment in the Georgia state militia at a rank “relative to his position in the U.S. Army.” In March, McLaws reached Augusta, Ga., where he wrote his letter of resignation, to the Army, dated March 14.

On March 23 the War Department accepted his resignation, one of the few U.S. Army officers to make a pain-free exit from the service. His first rank in state forces, from April 18, was major, assigned to staff duties. Before the end of June he was summoned to Richmond to assume command of the 10th Georgia Infantry in the Provisional Army.

Another Southerner, Captain Thomas Jordan, did not have to agonize over his decision or face the consequences for that decision because when the war came in April 1861 he was at home in Virginia on extended leave of absence from Fort Dalles, Oregon. Rather than report back to his post, he resigned his commission in May to accept a lieutenant-colonel’s appointment in Virginia state forces. He was P.G.T. Beauregard’s adjutant at First Manassas two months later, and escorted President Davis around the battlefield after the fighting stopped.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he Southerner whose actions brought the most opprobrium was Georgia-born David E. Twiggs. A superannuated brigadier general in 1860, the 70-year-old Twiggs had only been in command since December, an assignment he did not want in the first place. While the lame duck Buchanan administration dithered, Twiggs was left twisting in the wind in San Antonio without instructions. In mid-January he sent in his resignation letter and waited for his replacement to arrive. The War Department relieved him later that same month, but he did not receive the order for another two weeks. Meanwhile, his status was up in the air: Was he simply relieved of command or was he now a civilian? In the meantime, Texas had seceded on February 1 and moved quickly to seize all U.S. military property and forces in the state. Pro-secession state militia surrounded Twiggs’ headquarters and rather than make an Alamo of it, he meekly capitulated. Northerners and Southerners alike were shocked at his perfidy in handing over 2,600 men and 19 military posts without a fight. Twiggs went straight from U.S. service to Confederate service without the formality of his resignation being accepted, thus removing even that legal cover for his actions. President Buchanan cashiered him “for treachery to the flag of his country,” and he surely would have been tried for treason had he survived the war. Instead, Twiggs died on July 15, 1862.

All of the Southern-born officers who left their posts out West in 1861 at least tried to do the right thing by resigning before taking off. However, many also followed the example of Robert E. Lee back in Virginia by considering themselves officially separated from the U.S. Army—and released from their oaths—when they submitted their letters of resignation, rather than waiting for their resignations to be accepted. Some took the next step by asking their immediate superior for what amounted to a free pass—a leave of absence of 30 days, 60 days, or even six months to go home to await their release. But if leave of absence was not granted or their superiors did not release them promptly, they left anyway. Fortunately, the post–Civil War U.S. Army under Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was inclined to be forgiving. None of those ex-Confederates who survived the war paid a price for their actions from four or more years earlier. For those who didn’t survive the war, like Lewis Armistead and Richard Garnett, death trumped any concern over being prosecuted. For the rest, their journey from active U.S. Army officers to making war on the United States, which could have prompted their prosecution for “treason,” was forgiven—with one glaring exception, the execrable David Twiggs, despised by both sides.

Richard Selcer is the author of 11 books, including Lee vs. Pickett: Two Divided by War and Written in Blood, Volumes 1 and 2. He is currently working on a biography of George Pickett.