Undoubtedly, most Vietnam War helicopter pilots would consider any mission they flew without drawing enemy fire to be a resounding success. But not David L. Porter and his fellow U.S. Army aerial scout pilots flying daring “hunter-killer” combat missions. They would deem missions with “no enemy fire” to be dismal failures. The scout pilots’ raison d’etre was to tempt enemy ground troops and anti-aircraft gunners to fire at the vulnerable scout “hunter” light observation helicopters, or LOH, thereby exposing enemy positions to attack by the scout’s “killer” partners—typically heavily armed AH-1 Cobra helicopter gunships.

In effect, aerial scout helicopters were the hunter-killer missions’ “juicy bait” dangled tantalizingly in front of enemy ground troops to get them to “bite” and unleash streams of automatic weapons fire. Seeming to defy common sense (not to mention self-preservation), “success” for scout pilots literally meant “taking fire.”

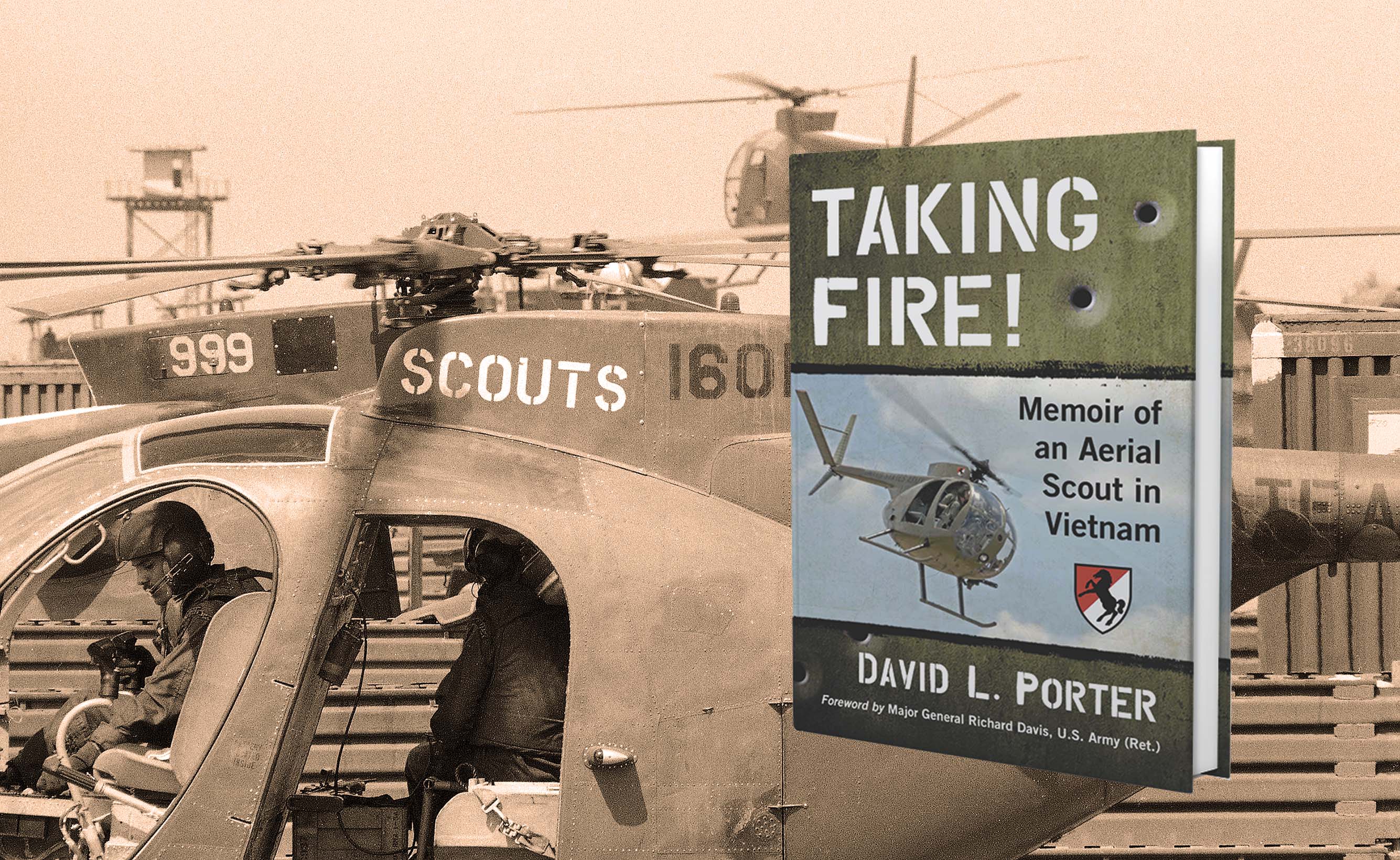

Porter’s excellent Taking Fire!: Memoir of an Aerial Scout in Vietnam is a concise, detailed and well-written 174-page account of his experiences as a young scout helicopter pilot during a 1969-70 combat tour in Vietnam with the air cavalry troop of the famed 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, the “Blackhorse Regiment,” based in Quan Loi, between Saigon and the Cambodian border.

During his 364-day tour in Vietnam, Porter flew “around 200” aerial scout missions while assigned to hunter-killer team duty. He describes those missions’ tactical concept: The Hunter-Killer tactic was developed over time because of the requirement to find and destroy an elusive enemy in terrain that masked the enemy from traditional reconnaissance techniques…

The operation stipulated two basic tactics: finding the enemy; and, once he was found, fixing and fighting him. The Hunter-Killer Team was designed around two aviation components: 1) The Hunter—one OH-6 Scout LOH flying at low-level, searching for VC, reporting his observations to the overhead Cobra; and 2) The Killer—one AH-1G Cobra flying at altitude, providing cover for the Scout below, reporting scout observations, and if necessary, reacting to enemy contact.

The capabilities of both aircraft meshed perfectly to support Hunter-Killer work. The LOH was small, quick, hard to shoot down, and elusive. The gunship was lightning-fast, heavily armed, and lethal. Hunter-Killer operations drew heavily on the skills of the pilots involved and demanded extraordinary team work and trust from both participants.

Porter’s hunter-killer team missions were inherently dangerous. Each was potentially fatal. Porter’s four Distinguished Flying Crosses and Air Medal with a “V” for valor device attest to his courage.

As a bonus for Vietnam War history buffs, Porter’s book goes beyond his combat adventures to also recount his experiences in the Army from induction in 1968 through the end of his Vietnam tour, including his time at the U.S. Army helicopter flight school in Fort Wolters, Texas, and Fort Rucker, Alabama. It is a fascinating, firsthand account of military service in that era.

There is an exceptionally detailed rendering of “daily life” in Vietnam for a first lieutenant in the 11th Armored Cavalry’s air cav troop—in-country processing; living and working conditions; infrequent but potentially deadly surprise mortar/rocket attacks; good and bad interactions with subordinates, peers and superiors; leadership lessons gained by direct experience; and—perhaps predictably given the American GI’s propensity to attract pets, primarily canines—a description of the “unit dog,” a mongrel pooch inevitably named “Scout.” (My field artillery battery’s pet dog, “Frag,” unfortunately met an ironic end when a nervous infantryman standing perimeter duty one dark night tossed a fragmentation grenade at some suspicious noise outside the wire. It was “Frag” wandering around sniffing discarded C-ration cans.)

Porter’s memoir is a solid account of a combat assignment in Vietnam that has too often been overlooked.

This reviewer’s only complaint is the number of minor errors of the type that occur frequently in today’s publishing business and which should have been fixed by publisher McFarland’s editor. These small but nonetheless irritating mistakes unnecessarily detract from his otherwise excellent narrative. For example, the French Southeast Asian empire was in “Indochina” not “Indonesia;” the standard Viet Cong/North Vietnamese Army mortar was the Soviet/Chinese “82 mm” not “81 mm”; the 1972 Battle of An Loc was during the failed NVA “Easter Offensive” not “the final collapse of South Vietnam” in 1975. However, these editing mistakes should not detract from Porter’s superb and informative memoir. V

Jerry Morelock is senior editor of Vietnam magazine.

For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: