On August 20, 1863, in the middle of the night, Private John Futch and 12 other veteran soldiers from

the 3rd North Carolina Infantry slung on their ammunition-packed cartridge boxes and escaped into the woods, hoping they would eventually reach their North Carolina homes. In five days, Futch and his comrades, all from four counties in the eastern part of North Carolina, covered a little more than 30 miles. As the band neared the banks of the James River, a squad from the 46th North Carolina suddenly sprang out of the woods with their rifles leveled, and their commander, Richardson Mallet, screaming at the fugitives to surrender.

It appears that one of the deserters fired a bullet into Mallet’s chest, setting off a heated gun battle of some 30 shots. During the chaos at least one deserter was killed, another was wounded, and one man likely escaped. The remaining 10 soldiers surrendered while Mallet lay on the ground with a fatal wound.

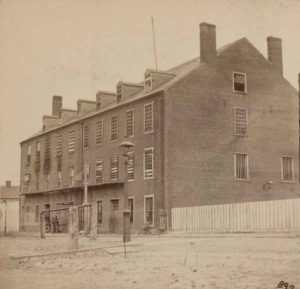

The deserters were soon incarcerated in Richmond’s notorious Castle Thunder, and the severity of the crime ensured that no possible deviation from military law would prevent the army from carrying out the death penalty. When the court was eventually called to order, guilt was presumed.

The Confederacy’s court-martial records were either destroyed or lost during the 1865 evacuation of Richmond, Va., but military service records prove that the deserters from the 3rd were not repeat offenders when it came to unauthorized leave. Four were previously wounded in battle and one was noted for bravery in several engagements. Two had been captured and exchanged, and three were conscripts. Only one soldier had a record of previously being absent without leave. They were all seasoned veterans who understood the penalties for desertion, and who needed to plan, deliberate, and organize their escape prior to August 20.

[dropcap]J[/dropcap]ohn Futch was functionally illiterate, but in letters dictated to other comrades, many of whom were barely literate themselves, Futch gave subtle indications to his wife, Martha, that he was returning to North Carolina with or without a furlough. On August 16, he told his wife, “I want to come home the worst I Ever Did in my Life.” Futch could not say much more to Martha, because “it is Said our Letters is Broke open and red.” Four days later, on August 20, Futch nearly stated his true intentions, hinting that his days in the army were numbered. As he dictated this final letter, he must have known that he would be vanishing from the army that night. “I expect to bea home before long,” he promised.

A New Hanover County resident, Futch had enlisted in the 3rd North Carolina in early 1862. His brother Charley and a cousin had been serving in that regiment since summer 1861. Within a few weeks of joing the army, Futch fell ill with an undisclosed ailment that kept him in military hospitals until early 1863, when a physician cleared him to return to the ranks. Futch boarded a train that took him past the Goldsboro hospital, where Martha had often been at his bedside, nursing him back to health. The scene was emotionally wrenching for the North Carolinian, “Oh I thought of old times when [I] passed Goldsboro…,” he dictated, “[and] when I looked at that old hospital I all most Cryed.”

When Futch rejoined his regiment, snow, howling winds, and meager rations enervated his already weakened body, and he spent most of his time secluded in his tent, dictating letters about his poor health and the army’s indifference to his worsening condition. He continued to lobby his captain for a discharge. “My health is so bad and it is so cold here that I am perfectly miserable,” he explained shortly after his arrival, “and I am doing my Country no good and myself a great harm.” Futch’s wife urged her husband to leverage his feeble health to secure a military discharge. “Dear husband,” Martha wrote on March 29, 1863, “i learn that you have not goin before the [Medical] bord and i want you to go….[I]f you wanted to come home as bad as i do want you to come you would go before it every day and i want you to do it and tri to git home.” Futch followed her pointed advice, pressuring his officers to give him an interview with the board of surgeons.

In spring 1863, when it became apparent that a medical discharge was out of reach, Futch faced the reality of service until the war’s conclusion. He did not want to be anywhere except by the side of his wife, whose letters to him were by turns distressing and affectionate. She did not spare John bad news, telling him of thieving bandits, of the difficulties in receiving financial assistance from the county, of husbands abusing their wives, and of Union raids.

Futch’s wife planned to visit the army that spring with provisions and clothes for her needy husband. On April 14 she wrote, “i never in dured so much trubles in my life be fore it semes lik it will kill me if i dont see you one more time dear husban i want to no how you air feren and if you have worm close and slep worm.”

The reunion did not take place, however, due to the opening of the Chancellorsville Campaign. John worried that he would be killed, leaving his wife to face the world alone with their infant child. It was the first time that Futch had fought, and he later told his wife that as the bullets started flying, he felt certain that “I had seen you for the last time.”

Futch sought refuge in a hospital to calm his fatigued mind. A few days later, with his spirits restored, he dictated, “I never saw the like of the dead never in my life.” In his soul Futch knew that “God brought me though saft.”

By the end of May, Futch had dictated five letters of varying lengths to his wife. His language—as recorded by his comrades—lacks the popular figurative expressions such as “sublime bravery,” “fearlessness,” or “everyone faced to the front” used by so many Civil War soldiers to convey an exaggerated picture of unity. Rather, Futch admitted to his wife that many in his regiment ran away from the firing line, including one terribly frightened man who defecated in his pants while under enemy fire. Futch, in dictating his letters, spoke candidly with his comrade about the physical and emotional breakdowns of their fellow soldiers. The openness between the two veterans suggests that not all Civil War soldiers retreated into themselves after a battle, seemingly lost in traumatic thoughts and unable to admit feeling, terrorized by fear.

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]utch hoped that the summer campaign would bring the war to a conclusion, but any optimism he felt was washed away when he forded the Potomac River. “I Crosed over the river yesterday,” he reported on June 19. “I didant Want to Com by any means Nor I Dont like this state.” As he moved into the heart of Pennsylvania, Futch became more discouraged. Worn down with worry and unable to rid himself of the haunting memories of Chancellorsville, Futch sensed that the next battle would be his last. “You must take the best Cear of your self you Can mah [Martha],” he wrote, as he was losing hope that “I will get home some time before I Dy.

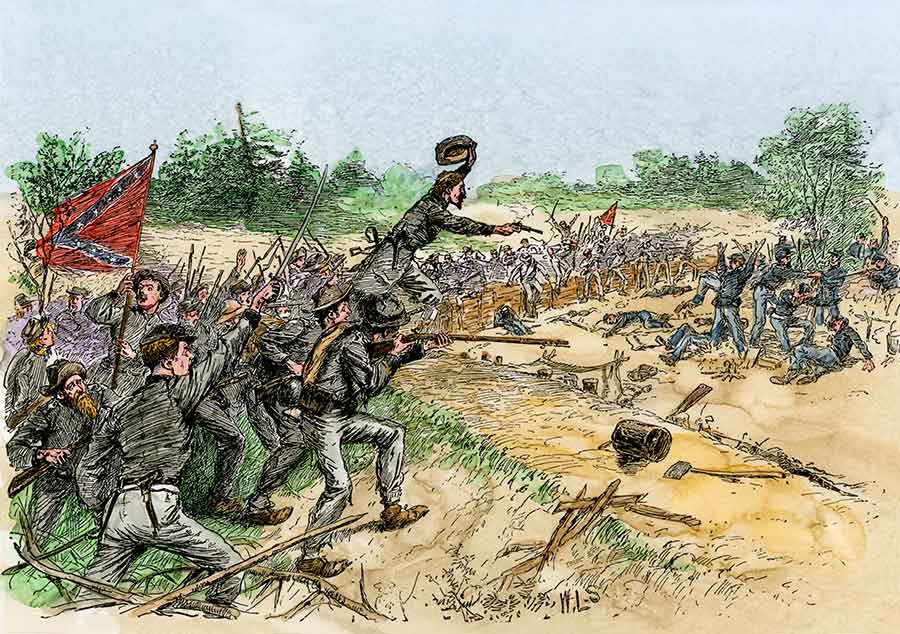

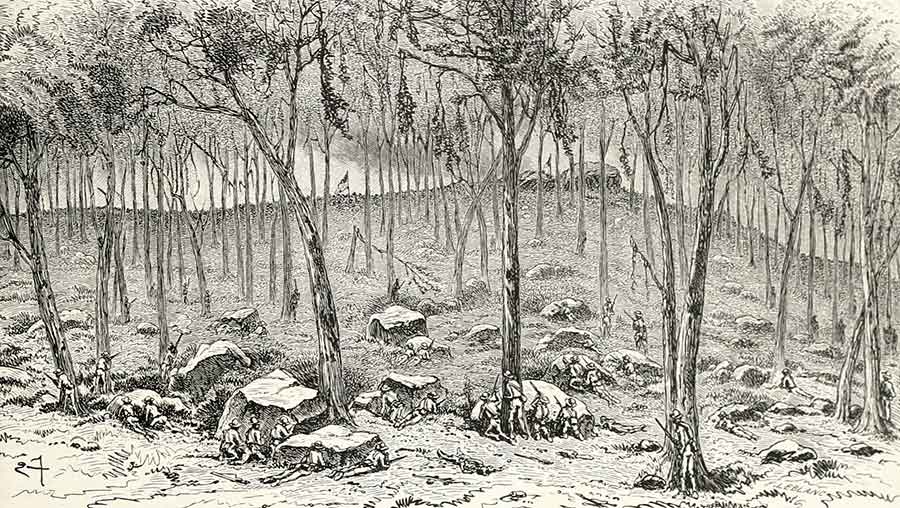

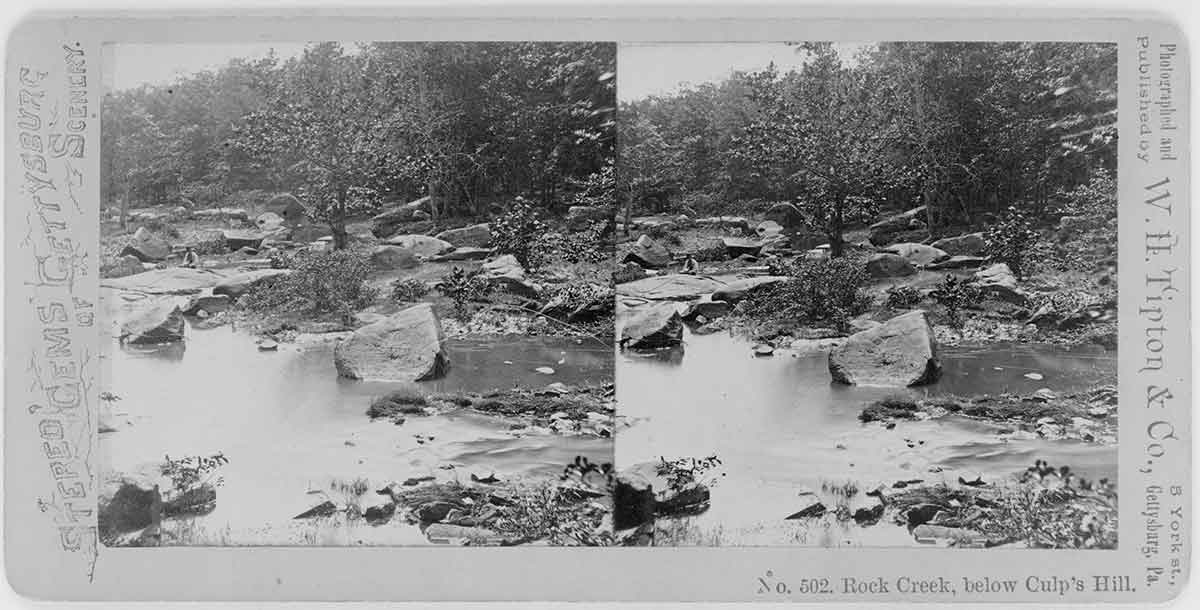

John and Charley had been able to turn to each other for counsel and comfort, but on July 2, the brothers advanced up Culp’s Hill and a Yankee bullet sliced into the top of Charley’s head. Futch carried his fatally wounded brother to the banks of Rock Creek, and stayed by Charley’s side. At 2 a.m. July 3, Charley died, but for John, the ordeal continued.

“Charley never spoke after he get wonded and he wanted to go home Mity bad before he died,” John recounted to a comrade. “He was kild at gettiesburg PV pore felar he got kild a long wase from home I was very sary that I codent get a cofen to bearey him but I breared him the best I cod it was something that I never expected to haft to do but we dont know what we will do til he gets in the ware it.”

For John, there was no consolation in giving a brother to the Confederate cause, no sense that a higher purpose had been served. Charley’s departure from this world of trials and tribulations was the only solace for Futch. “I beleav he is hapy,” he told his family, “and no doubt far better off than any of us.”

After Robert E. Lee’s army retreated to Virginia, constant marching continued to the beginning of August. Many of Lee’s veterans described themselves as broken down from heat exhaustion, hunger, and mental fatigue in what historian Joseph Glatthaar describes as a logistical and discipline crisis that endangered the very existence of the Army of Northern Virginia. Futch’s shoes were in tatters, forcing him to march in bare feet that eventually callused over with painful sores. “Yet i hast to go bearfooted the botom of My foot is as thick…[with] sores that i ever had.”

The procession of mournful letters Futch dictated during the Gettysburg retreat reveal a man convulsed in utter despair. Futch made no attempt to hide his desolation from the comrades who wrote down his words. “Since the Death of Charley I am so lonesome I do not know what to do,” he dictated. Throughout his correspondence, Futch’s dictations do not fit into the code of Southern honor that pushed men to project a mastery of emotional control. White Southern men were not supposed to acknowledge their frailty and look helpless. No self-respecting man could earn community acceptance without projecting mental and emotional toughness.

Futch, however, told those in the ranks and at home that he was drowning in the depths of depression. “I don’t want nothing to eat hardly for I am all most sick all the time and half crazy,” he confessed to a comrade on July 19. “I never wanted to come home so bad in my life.” Futch’s exceptional letters suggest that military life did not necessarily wrap the soldiers in an emotional cocoon. In fact, they could and did open up about the dangers of battle, a longing for home, their love of their wives and children, and their desire for the killing to stop.

In five letters to his family dictated from July 19 to August 6, Futch repeatedly talked about his brother’s agonizing death. He needed to escape for his own sanity and for his family’s survival, in contrast to scores of other Confederates who, as historian Aaron Sheehan-Dean has argued, “increasingly explained their participation in the war in terms of protection of their loved ones. The result was a new masculinity, one that required both affection and hostility, the former directed toward one’s family and the latter directed toward its enemies.” By the end of the Gettysburg Campaign, Futch reached the conclusion that the army did not offer the best protection for his home. This was not an issue of weak morale or a question of nationalism for Futch, but of interests that were at odds with Confederate authority.

He finally reached the momentous decision to desert, which can only be interpreted as a powerful assertion of political motivation and a decision born of desperation. The previous February he had seen a comrade get his head shaved and then drummed out of camp for cowardice. “I dont want this to Be my case,” he insisted at the time. But by the end of July, Futch could stand it no longer, and he told a comrade to let his family know that he was bound for North Carolina even if the army said no: “I am going to come before long if I have to Runaway to do it….Let me know how the times is in old Hanover for I want to be there so Bad I can taste it.”

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]lmost a month would pass before Futch fulfilled his promise to desert. A focused examination of the Army of Northern Virginia during that time is instructive, for it offers insight into the ways the press, the government, and the Confederate Army collaborated to discipline the rank and file. To scare, cajole, inspire, and force Lee’s men to do their duty, a rhetorical campaign appealed to Confederate veterans as Christian soldiers who stood as the last line of defense between their families and maniacal Yankee hordes and vengeful African Americans. Jefferson Davis’ proclamation to all Confederate troops on August 1 lays out the interlocking ideas about race, manliness, and soldierly duties employed to direct the political behavior of Southern enlisted men. “Fellow-citizens,” the president announced, “no alternative is left you but victory or subjugation, slavery, and the utter ruin of yourselves, your families, and your country.” Davis insisted that Union armies were intent on elevating blacks over white men.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Lee praised the executive declaration as an “earnest and beautiful appeal.” Lee’s response rested on cultural and class assumptions that prevented him from fully appreciating how inequities in power and resources were contributing to his army’s near-implosion. Morality, character, and courage, the general stressed, were the critical issues when reforming deserters. “Our people have only to be true and united, to bear manfully the misfortunes incident to war, and all will come right in the end,” Lee concluded in a letter to Davis. Less than two weeks before the president’s proclamation, Lee issued the following plea to the troops: “To remain at home in the hour of our country’s need, is unworthy of the manhood of a Southern soldier.”

The Confederate press essentially allied itself with Davis and Lee in turning desertion into a problem of individual character and manliness and, in effect, burying any questions of how political and military decisions were responsible for discouraged Confederates. Southern papers frequently ran stories that were purportedly from soldiers. After Gettysburg numerous Southern papers published the popular article, “A Deserter’s Confession.” A Georgia deserter named “James” supposedly narrates the piece. On arriving home, James confesses that he had run away. “Oh! James!…” his wife exclaims, “What will the neighbors say? What will General Lee think?” James did not have an answer until he read Jefferson Davis’ August proclamation. He was so touched by the president’s exhortations of a potential race war that he “sat down and cried like a child.” After this cathartic experience, James left for Virginia, promising never to desert again.

The political purpose of “A Deserter’s Confession” is ridiculously transparent, but we know little about how less-privileged Confederate soldiers critically read and responded to the dominant message from the press, the pulpit, and the government. We cannot assume that soldiers accepted elitist messages uncritically, nor should we assert that the men rejected the words of elites as outright propaganda. We do have evidence of a skepticism on the front lines that would sometimes descend into cynicism. Soldiers knew that their officers and politicians, in collaboration with the press, were intent on controlling their behavior and shaping their beliefs.

In the chaotic two months that followed Gettysburg, the press called for punitive measures against deserters; Lee backed military executions; and Davis warned of an abolitionist enemy. All of those actions helped form the backdrop behind the trial of Futch and the nine other captured deserters who were convicted of murder and desertion. In a horrible miscarriage of justice, there would be no chance for an appeal, no chance to ask for clemency, and no opportunity to alert loved ones of their fates.

Major General Edward Johnson’s divisional headquarters informed Futch’s brigade commander, Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart, on September 4, 1863, that the deserters would be shot at 4 p.m. the following day. “The proceedings of the Court & Gen Order No. 62 from these Hd. Qrs. will not be read to the prisoners until day light to-morrow morning,” the orders stated. “You will take all possible means to secure them, handcuffing or tying them & keep the matter secret until the proceedings are read to the prisoners.”

No letters from Futch from this time survive, nor do the court-martial transcripts. Although we lose touch with Futch, we do have access to the Confederate elites who possessed the power to use violence against their own citizens and could shape the public understanding of the killing.

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he 10 condemned Confederates were manacled and escorted by an armed guard through Richmond to board the 6:30 a.m. train for Gordonsville, probably not knowing they were returning to the Army of Northern Virginia so that their comrades could carry out the court-martial’s death sentence. As dusk settled, the party reached the provost guard tent of Johnson’s Division. The heavy guard remained, and anyone trying to communicate with the prisoners was pushed away. Early the next morning, 3rd North Carolina Chaplain George Patterson, an Episcopal priest, conferred with Futch and his comrades.

Patterson spoke to them about the need to prepare for the afterlife, and the newspaper accounts agree that Futch and his comrades found Jesus for this first time. Whether this spiritual awakening actually took place is hard to say, though it is clear from his correspondence that Futch had long ago accepted Christ as his savior. In fact, he even drew a pair of hands, forefingers pointing up to the heavens, at the end of one of his letters. It also seems unlikely that the military would have given correspondents access to the prisoners. But the truthfulness of the story is secondary to the intent of the authors, who portrayed the North Carolinians as men who were capable of committing a crime because they did not believe they answered to God. In a sense, the press was actually suggesting that the Confederate army, in taking the lives of these men, was actually saving their souls.

The veterans of Johnson’s Division were ordered to the drill ground on September 5 with the explicit instruction to leave their muskets in camp. Once the men were in place, General Johnson and his staff rode into the center of the square carrying a small national flag. The Confederate flag visually reinforced the primacy of the national government and the dire consequences of dishonoring that banner. Twenty minutes passed until the afternoon stillness was broken by the methodically slow beat of the death march. Suddenly the ranks parted and the doomed soldiers appeared, marching in step to the grim cadence. They were halted at the spot where they would lose their lives. The executioners appeared next, 120 men with fixed bayonets.

When the column halted in front of the stakes, the prisoners were forced to stand and face their executioners while the officer of the day read the sentence. The Rev. Patterson stepped forward next to deliver what one observer described as a prayer of “great feeling.” Patterson’s prominent place in the procession sanctified the killings as a divinely ordained moment of justice, not just a raw exercise of man’s power. After Patterson finished his prayer, two guards escorted each prisoner to a stake and made them kneel as their arms were tied behind them to a plank attached to the top of the stake. The guards bandaged the eyes of the condemned and made sure that their hats rested over the bandages. A hushed silence momentarily prevailed until the cries of the condemned pierced the air: “‘Lord have mercy!’ ‘Oh, my poor mother!’ and ‘Oh save me, save me!’” yelled the soldiers in disarrayed tones. Whether Futch was one of those men pleading for his life, we will never know.

While the condemned begged for mercy, the executioners quickly formed squads of 10 men. Five carried loaded muskets; the other five had blanks in their rifles. They stood just 14 feet away from Futch and his comrades. As soon as the officer of the day yelled “ready, aim, fire,” a ragged volley ripped into men who just two months earlier had faced enemy shells on the slopes of Culp’s Hill. When the smoke cleared, it was discovered that a few of the North Carolinians were gasping for air, their bodies still shaking with life. Twenty members of the reserve squad were quickly ordered forward, and they fired repeatedly into the wounded survivors. To impress upon the witnesses the finality of the punishment and the future risks of deserting, Johnson’s entire division, regiment by regiment, marched in silence past the lifeless bodies. The march was deliberately completed in slow time, some 70 steps a minute, so that the soldiers were subjected to the military’s absolute control over the bodies of the living as well as the dead.

Most soldiers were not overcome by a renewed sense of patriotism when they saw comrades shoot their own. The ghastly sight sickened patriotic soldiers, but they were also quick to justify military executions as an unfortunate necessity in preserving order in camp and discipline in battle. Less ardent soldiers had a more difficult time reconciling themselves to the death penalty. “It was a terrible sight, and God grant that I may not be called to see anything of this kind again,” wrote North Carolinian Thomas Armstrong a day after the execution. “Most of them were good soldiers and brave men,” Armstrong added. “This being their first act of disobedience.”

Another North Carolinian thought the execution was a senseless act that would ultimately turn more men against the Confederacy. “We formed a square so that all could see and after they were shot we then were marched by them,” he recounted. “This was done to have a good affect on the men but I doubt its doing much good for our soldiers are hardened to such scenes. And they all say that they ought to have been imprisoned and there work for the government—I think this would have been better myself.” Yet even soldiers critical of the execution could not ignore the warning of this death ritual: The military establishment would not be a benevolent master toward runaways. And when John Futch disappeared from camp on August 20, it was near-collapse of Lee’s army that enabled him to act upon his own conception of what an honorable Christian soldier should do, when suffering and loss—both at home and in the ranks—became so unbearable that the act of desertion appeared to be the only road to survival.

Peter S. Carmichael is the Fluhrer Professor of History and the director of the Civil War Institute at Gettysburg College. This article is adapted from his new 2018 book, The War for the Common Soldier: How Men Thought, Fought and Survived in Civil War Armies, which will be published by the University of North Carolina Press. Used by the permission of the publisher, www.uncpress.org.