The RAF played a pivotal role in the 1920 campaign against a dervish bandit leader in British Somaliland.

For two decades prior to World War I, Mohammed bin Abdullah Hassan, the self-proclaimed Mullah of Somaliland, was a persistent thorn in the side of British colonial authorities in the arid, sweltering East African protectorate. To the British he was the “Mad Mullah,” a quasi-religious bandit leader intent on plunder and disruption who imposed his will through savage executions and mutilations. To his adherents he was a messianic Sunni holy man, jihadist and freedom fighter. Regardless, the Mullah and his ferocious Islamic fundamentalist dervishes survived four major military expeditions sent against them by the British, in fighting so intense that no less than nine Victoria Crosses were awarded. Although the Mullah was defeated in battle several times, he was never captured.

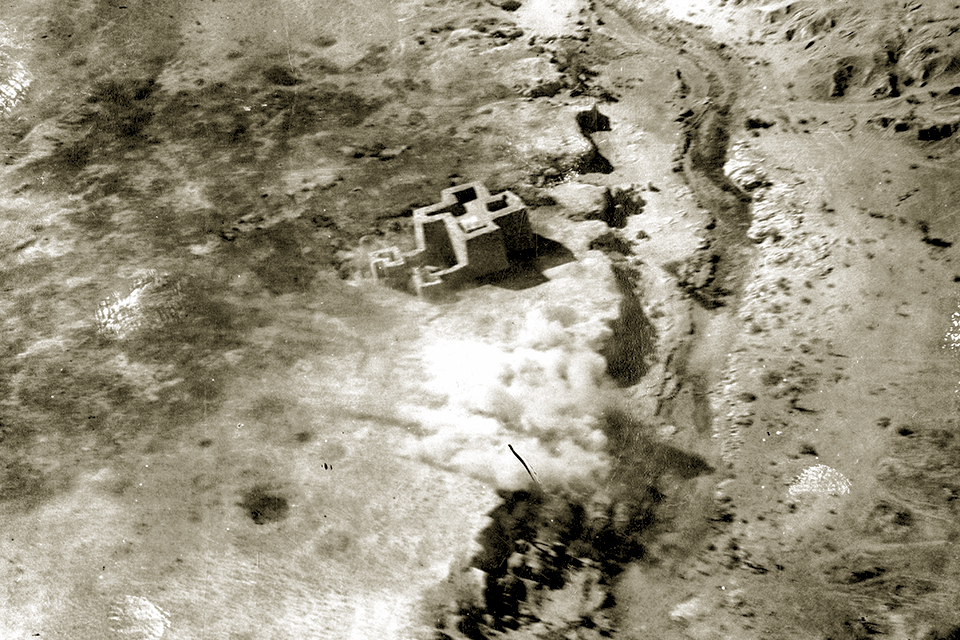

The withdrawal of most British forces from Somaliland to other theaters beginning in 1914 allowed the Mullah to consolidate his position by building stone forts and projecting his power across vast areas. Consequently, by 1919 the Mullah’s hold on Somaliland had become so strong that the British were faced either with abandoning their protectorate or with using a military force estimated at two infantry divisions to deal with the bandit leader. In the bleak postwar economic climate, this was an unaffordable option for the British War Office.

While visiting England for urgent discussions at the Colonial Office, Geoffrey Archer, the governor-designate of Somaliland, was pointedly directed by Colonial Undersecretary Leopold Amery to discuss the situation with RAF Chief of the Air Staff Sir Hugh Trenchard. In the face of War Office opposition, the RAF seemed to offer the only chance of a successful outcome in Somaliland. Fortuitously, the embattled Trenchard was then fighting to preserve the RAF as an independent service, despite tough opposition from the army and Royal Navy, which favored carving up the air service.

After his meeting with Trenchard, Archer recalled: “It was a situation that exactly met Air Force requirements. Here was the opportunity the RAF required to demonstrate that the safest, cheapest and most effective way to conduct ‘Savage Warfare’ in such inhospitable regions as Northern Somalia, the Aden hinterland and Iraq, was from the air, with the support of a limited number of ground troops.” Ultimately, with the support of Winston Churchill, then secretary of state for war, at a conference on June 2 the Colonial Office and the prime minister accepted Trenchard’s proposal for the dispatch of a self-contained air component, designated Z Unit, to Somaliland. The force would comprise 10 two-seat de Havilland D.H.9 reconnaissance-bombers, with 36 officers and 183 airmen.

In late October 1919, Z Unit’s advance party, including its commanding officer, Group Captain Robert Gordon, with Wing Cmdr. Frederick W. Bowhill and airfield construction personnel, left England for Aden via Egypt. In Aden they transferred to an Arab dhow that took them, after an uncomfortable crossing, to the port of Berbera in northern Somaliland. Before landing on November 21, the airmen changed into civilian clothes and assumed the cover of “oil experts,” part of an elaborate fiction designed to deceive the Mullah’s spies into thinking that their arrival as airfield builders was connected to a long-planned oil drilling operation. Berbera duly became their main base, with Eil dur Elan, to the east, as the principal advanced airfield.

Having left England on November 13, Z Unit’s main party collected additional personnel in Egypt before embarking from Alexandria on December 21 aboard the seaplane tender HMS Ark Royal, with all the aircraft, motor transports and 800 tons of supplies. Arriving in Berbera on December 30, they immediately started unloading, then reassembled and flight-tested the D.H.9s— work that was completed on January 19, 1920.

The first and by far the most significant operation took place two days later, when six D.H.9s left Eil dur Elan to bomb the Mullah’s forts at Medishi (later spelled Medistie) and Jid Ali (Jideli). Governor Archer saw them off: “I watched the machines tuning up at dawn and their departure in close formation at 7 a.m. to deliver the first aerial attack on the haroun [fort] at Medishi. It had been impossible to reconnoiter beyond Eil dur Elan from the air beforehand owing to the paramount need for secrecy, to ensure the ultimate attack came as a complete surprise. As luck would have it the 21st was very cloudy, and consequently the massed flight missed its objective and returned with a nil report.” One D.H.9, however, had force-landed at Las Khoreh after developing engine trouble. Several hours later, with their engine repaired, its crew was flying back to base when they spotted Medishi—and immediately began a bombing run.

Earlier the Mullah, who had never seen an airplane, had watched in bewilderment as the massed formation passed unknowingly over his stronghold. One aide reportedly told him that they were the “Chariots of Allah”come to carry him up to heaven, while a Turkish adviser claimed they were a Turkish invention sent with a message for the Mullah from the sultan in Istanbul. Convinced that the machines were indeed bringing important envoys, the Mullah donned his finest robes and sallied forth with his retinue to wait under the white canopy usually reserved for state occasions. He was still there waiting patiently when the solitary D.H.9 dropped a bomb from 300 feet that killed a close adviser and singed the Mullah’s robes. Any closer and the campaign might have been over then and there, since without their charismatic leader the factious dervishes would likely have dispersed back to their home areas.

Immediately after the D.H.9’s elated crew returned to Eil dur Elan to report their bombing of Medishi, the entire flight was ordered back into the air. During subsequent attacks on the Medishi and Jid Ali forts, at least 20 of the Mullah’s followers were killed and many others injured. Further bombing and machine-gunning sorties were flown over the next two days, setting fire to buildings, scattering precious livestock and causing heavy casualties. Although they were in disarray, the screaming dervishes kept up a defiant return fire—without any encouragement from the badly shaken Mullah. After the first attack, he had been promptly escorted to a cave 15 miles away.

Once extensive aerial reconnaissance on January 24 had established that the country around Medishi and Jid Ali was deserted, Group Captain Gordon declared an end to the independent air operations. For the campaign’s second phase, the D.H.9s would support ground troops of the British-officered Somaliland Field Force (SFF) in their pursuit of the Mullah, who was believed to be heading farther east, toward his other stronghold at Tale (or Taleh). The main RAF elements accordingly began moving to a forward airstrip at El Afweina, closer to Tale. Meanwhile the SFF captured the Mullah’s fort at Barran in the east, blocking his possible line of retreat into Italian territory.

The RAF bombed the Mullah’s fort at Galbaribur on January 29, and the next day cooperated with the Field Force in the pursuit of the bandit leader’s main column and personal retinue. D.H.9s attacked his baggage train en route to Tale, but again the Mullah escaped, hiding in a valley. In early February, after aerial reconnaissance indicated that his forces had reached Tale, three D.H.9s bombed the fort, one scoring a direct hit on the Mullah’s compound. Escaping unharmed, he fled with his mounted escort, hotly pursued by the Camel Corps. The Mullah eventually reached sanctuary in Abyssinia (Ethiopia), by which time only six of his most devoted followers remained. He died in exile in November 1920, probably from influenza.

Meanwhile, making it a tri-service campaign, Royal Navy forces from the gunboats HMS Clio and Odin had stormed ashore. They would capture and demolish the Mullah’s fort at Galbaribur.

The three-week campaign that successfully ended the Mullah’s influence in Somaliland had cost 27 lives among the British ground forces, a staggering reduction in casualties compared to earlier campaigns. The RAF’s Z Unit suffered no combat fatalities, although illness resulted in a number of evacuations. Overall, the military operations cost £150,000, with the RAF element costing £77,000— probably the cheapest war in British history.

Although the RAF had been used in India to support the army in controlling local unrest, it was the campaign against the Mad Mullah that proved independent air power could play a pivotal role in suppressing colonial rebellions. Thus it not only guaranteed the survival of the RAF as an independent service, it also set the pattern of air policing for the next two decades, notably in Iraq.

Describing the successful conclusion of the Somaliland campaign in the London Gazette of November 1, 1920, Governor Archer recorded: “For this the credit is primarily due to the Royal Air Force, who were the major instrument of attack and the decisive factor. They exercised an immediate and tremendous moral effect over the dervishes, who in the ordinary course are good fighting men, demoralizing them in the first few days.”

While the RAF clearly deserved Archer’s tribute, long-term success could never have been achieved without the unrelenting pressure on the dervishes maintained by the footsloggers and the Camel Corps of the Somaliland Field Force. Without it, the Mullah, or possibly a successor, might have regrouped the dervishes to fight again another day. To finish the job, boots on the ground were as necessary then as they are today.

Frequent contributor Derek O’Connor writes from the U.K. For additional reading he recommends: RAF Operations 1918-39, by Chaz Bowyer; and Personal and Historical Memoirs of an East African Administrator, by Sir Geoffrey Archer.

Originally published in the July 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.