No holds barred for Gilded Age’s most notorious lawyers

Howe and Hummel were criminal lawyers, in both senses: They were lawyers who defended criminals, and they were criminals who practiced law. The pair happily represented murderers, thieves, and prostitutes, but their crimes of personal preference were bribery, blackmail, and subornation of perjury. Gilded Age New York’s most famous lawyers, they also were among its wealthiest. “Howe and Hummel were as crooked as the horns of a Dorset ram,” wrote Richard H. Rovere in his delightfully droll 1947 book on the disreputable duo.

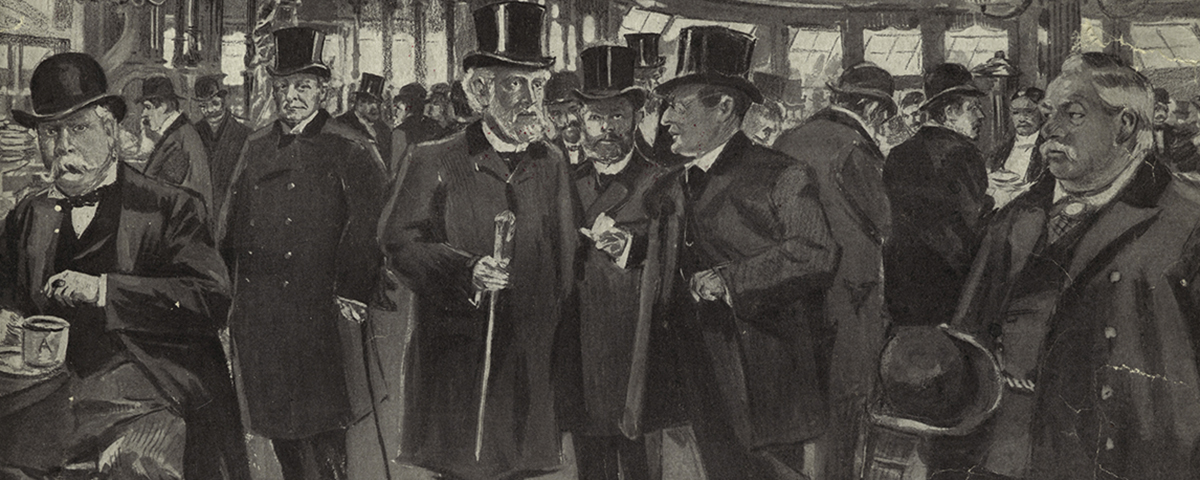

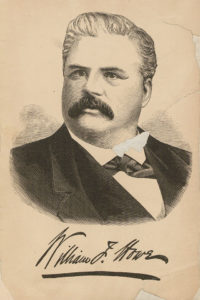

Visually, they made a stunning pair. William F. Howe, husky and portly, wore a white walrus mustache and a cheerful drinker’s ruddy cheeks. He favored loud suits, some of them purple, and

decorated his get-ups with diamond horseshoes, diamond sunbursts, and diamond clover leaves. “I like diamonds,” Howe explained. “I love their glitter and sparkle.” Abraham Hummel was barely five feet tall and skinny as a scarecrow. His suits were simple and black, impeccably tailored and pressed. “I’m a crook and a blackmailer,” Hummel told a reporter. “But there’s one thing about me—I’m a neat son-of-a-bitch.”

Howe claimed he was born in 1828 in Massachusetts, the son of an Episcopal minister. That was bunk. Biographers believe he was a Brit who fled to America in 1858 to dodge legal troubles. New York then required no specific training of attorneys, so Howe called himself a lawyer and started practicing. During the Civil War, he prospered defending draft dodgers and Union soldiers eager to depart the army. In 1863, Howe hired Hummel, 13, as an office boy. A product of Manhattan’s Lower East Side, Hummel proved so adept at hair-splitting, loophole-locating, and pettifoggery that Howe took him on as a partner. In 1869, they opened an office at 89 Centre Street, across from the city jail known as “the Tombs,” and erected a 40-foot illuminated sign reading “Howe & Hummel Law Offices.” The premises stayed open 24/7, convenient for accused perpetrators. The partners bribed policemen to recommend their services to miscreants the cops collared. Clear-eyed about their clientele, Howe and Hummel demanded payment in cash—up front. They convened daily to divvy the boodle.

Gilded Age Manhattan seethed with crime and vice, and Howe and Hummel had “a near monopoly over the legal business of organized crime,” Rovere wrote. The two represented the city’s most notorious street gang, the Whyos, and lesser outfits trading in forgery, pocket-picking, and loot-fencing, plus whorehouses all around the town. During a brief anti-vice crusade in 1884, police arrested 74 madams. Every single one listed Howe & Hummel as her attorney.

Crooked clients delivered profits but William Howe preferred a good case of murder. Between 1870 and 1900, he defended more than 600 accused killers, winning acquittals often enough to keep his bloody subspecialty booming. Many such clients earned headline sobriquets—“Hackensack Mad Monster,” say, or “Man Killing Race Track Girl.” When a client seemed guilty, Howe hired witnesses willing to perjure themselves for pay. Or he’d fog jurors’ minds with sentimental theatrics, posing a defendant’s elderly mother, weeping wife, and cuddly children front and center in court—and if a killer lacked relatives, Howe hired some. Once, he cast his wife and daughter in those roles. “Will you,” he asked jurors, “make that woman a widow, that child an orphan?” The jury wouldn’t, and voted to acquit.

A melodramatic ham, Howe had a gift for lachrymose summations, usually breaking into waterworks ahead of his audience. “The most accomplished weeper of his day,” reporter

Samuel Hopkins Adams declared. “His voice would quaver, his jowls would quiver, his great shoulders would shake, and presently authentic tears would well up in his bulbous eyes and dribble over.” Howe’s keening was contagious and frequently infected juries, delighting the attorney, who counted a wet-cheeked venireman an augury of absolution.

Unlike his showboating partner, Hummel worked in the shadows. Divorce-minded spouses flocked to him, but his passion was theatrical law. His showbiz roster included John Barrymore, P.T. Barnum, Lillie Langtry, Edwin Booth, and Little Egypt, a belly dancer arrested for exposing more than belly. A fan of Broadway musicals, Hummel loved hobnobbing with show folk; he fathered a child with longtime mistress Leila Farrell, a singer. His theatrical contacts inspired his other lucrative line—blackmail.

The scam worked like this: An actress or chorus girl would hook up with a rich married man. Upon ending the affair, she would hire Hummel to draft a breach-of-promise suit, charging that the lady’s paramour had seduced her by falsely promising marriage, in those days a crime. Hummel would summon the Lothario to his office, flash the affidavit, and offer, for $5,000 or $10,000, depending on the depth of the fellow’s pockets, to destroy the ominous document. When the philanderer ponied up, Hummel would make a show of setting the affidavit afire and pour his new friend a drink. Later, he and the showgirl would split the take. “It was an exceedingly low business,” George Gordon Battle, an attorney for some of Hummel’s victims, recalled. “But I’ll have to say this about Abe: I never heard of his framing anyone, and I never heard of a case where the girl didn’t get her half.”

Murder and blackmail made Howe and Hummel rich and famous in the late 1800s. The 20th century proved more trying. In 1902, Howe, 74, died in his sleep at his Bronx home. A New York Times obituary hailed him as “the Dean of the Criminal Bar.” Hummel carried on but soon ran afoul of Manhattan District Attorney William Travers Jerome. A reformer eager to combat vice and corruption, Jerome went at Hummel, a prominent symbol of same. After years of legal maneuvering, in 1907 Jerome convicted Hummel of suborning perjury. Hummel did a year in stir, then sailed to England, ill-

gotten fortune in hand. Except for a globe-

circling cruise in 1910, he toggled away the rest of his life between London and Paris, a dapper old gent often seen at the theater.

“If Abe Hummel’s head should ever split open,” reporter Wilberforce Jenkins wrote of the exiled grifter, “the secrets that would come out of it would require the publication of 16 extras a minute for nine years.” Alas, that never happened.

Abraham Hummel died in London in 1926, taking his juicy secrets to the grave.