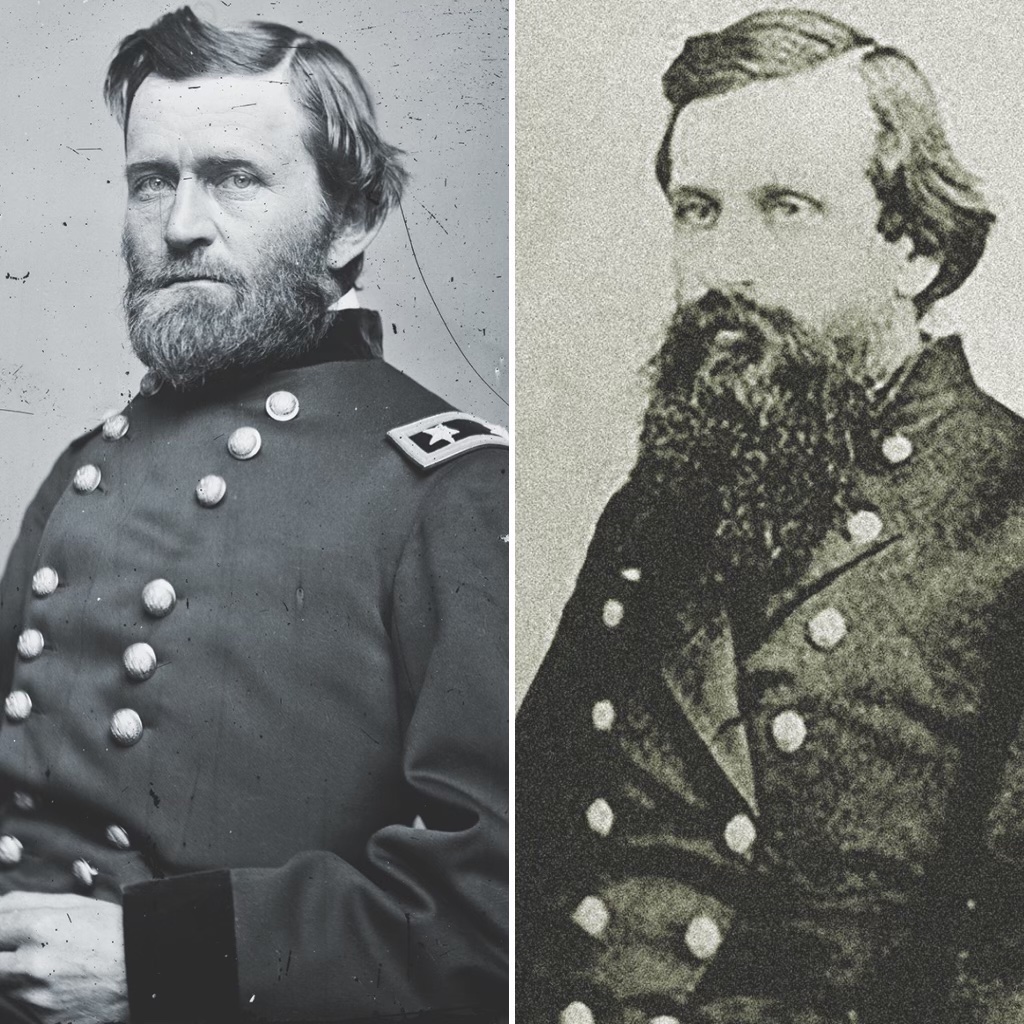

In October 1862, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took command of the Union Department of the Tennessee, establishing his headquarters in the village of La Grange, Tenn. Most of his 31,000 troops were stationed two miles away in the small railroad town of Grand Junction, about 45 miles south of Memphis and a few miles north of the Mississippi state line.

As Grant made plans to move farther south into the heart of plantation country, his principal focus was on the capture of Vicksburg, Miss., which would give the Union control of the Mississippi River—a major goal of the Lincoln administration since the beginning of the war. Grant, however, also faced the tormenting question of how to care for tens of thousands of former slaves who had begun steadily arriving within Union lines that fall. The U.S. government referred to these refugees as “contrabands of war,” or simply “contrabands,” essentially considering them captured enemy property.

“The arrival among us of these hordes was the oncoming of cities,” wrote the Rev. John Eaton, chaplain of the 27th Ohio Infantry. “There was no plan to this exodus, no Moses to lead it.…Their condition was appalling. There were men, women, and children in every stage of disease or decrepitude, often nearly naked, with flesh torn by the terrible experiences of their escapes.”

Readily accepting that these contrabands needed immediate help as well as a means to embark on their lives as new citizens, Grant on November 11 ordered Eaton to “take charge of the contrabands that come into camp in the vicinity of the post.” Eaton read Grant’s directive with dismay, however, and rode from Grand Junction to Grant’s headquarters in Hancock Hall—a large home, still standing, in La Grange—to plead for release from the order. “Mr. Eaton,” Grant countered, “I have ordered you to report to me in person, and I will take care of you.”

Grant would prove true to that.

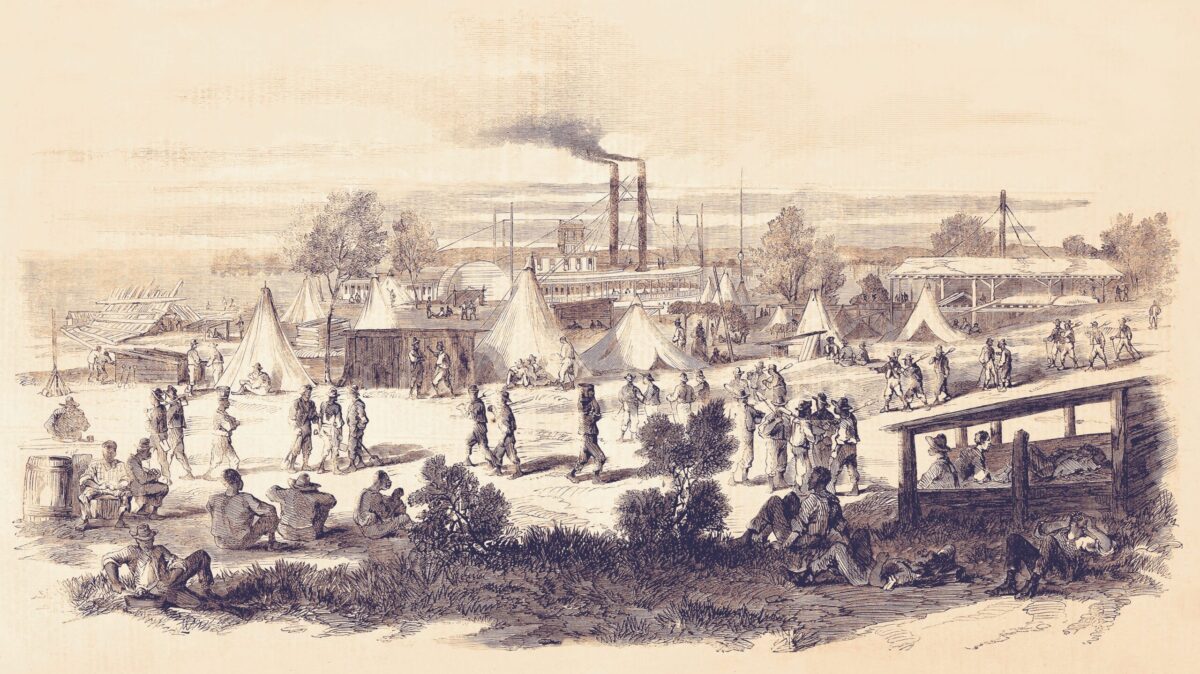

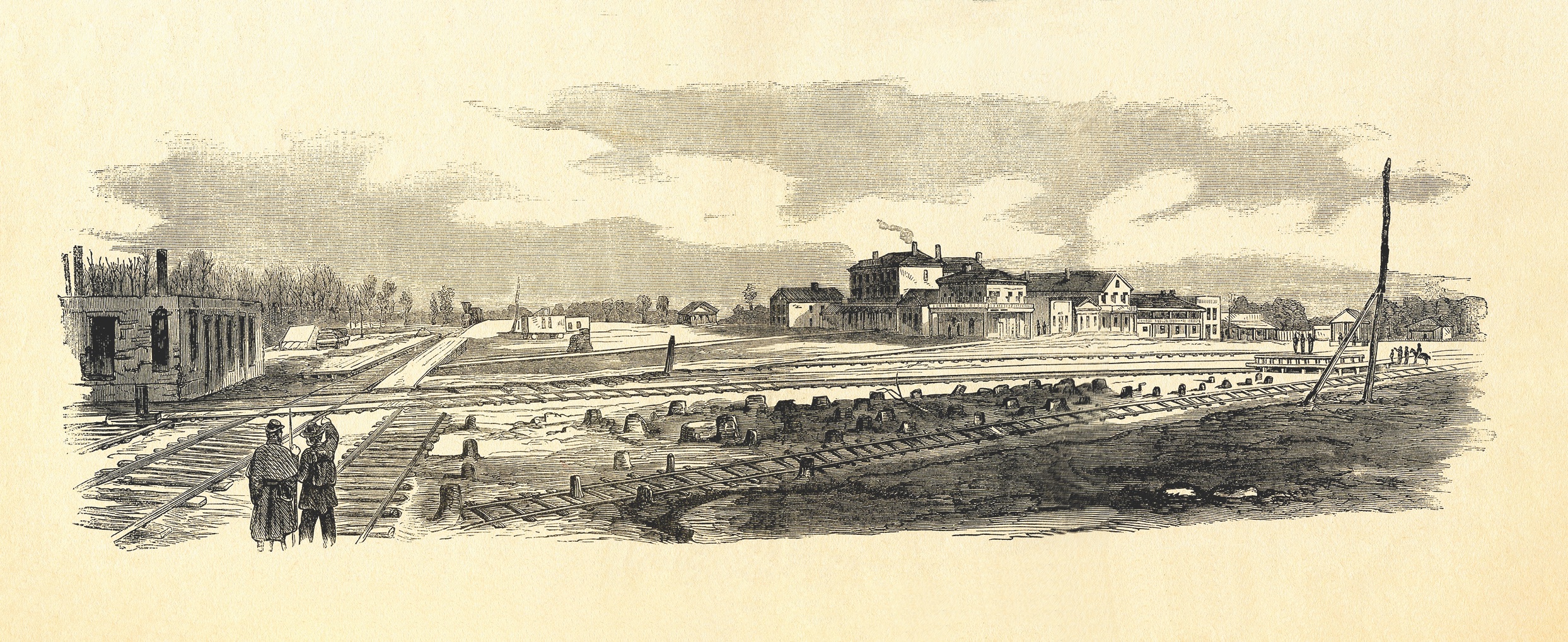

Eaton was named Superintendent of Contrabands and, as instructed, established a camp at Grand Junction. Tracks for the Mississippi Central Railroad and the Memphis–Charleston Railroad ran through the town, with a three-story railroad depot that was turned into a hospital. The camp was intended to shelter women, children, and men classified as “feeble,” but Army regulations prevented Grant from supplying food to these refugees, as rations were to be provided only for able-bodied male workers.

In 1885, Grant penned in his Personal Memoirs: “Humanity forbade allowing them to starve. With such an army of them, of all ages and both sexes, as had congregated about Grand Junction, amounting to many thousands; it was impossible to advance.” Among others who witnessed the swarm of Mississippi Valley refugees was a La Grange townsman and plantation owner, who commented in his diary on November 10, 1862: “[M]assing of contrabands. God only know when the Negros will stop.” And William Faulkner, who had heard stories from people who had lived through that period, described the scene in his 1938 novel The Unvanquished: “We couldn’t count them; men and women carrying children who couldn’t walk and carrying old men and women who should have been at home waiting to die. They were walking along the road singing, not even looking to right or left. The dust didn’t even settle for two days, because all that night they still passed.”

Grant would later acknowledge that he was greatly concerned about protecting his troops against the diseases and demoralization that might result from contact with the refugees. Nevertheless, he was not about to disregard the hardship in store for this helpless lot as winter approached. Initially, Eaton was overwhelmed by the contrabands’ want and destitution, limited as he was at first to a staff of one soldier per thousand refugees. The chaplain was uncertain how to protect, feed, clothe, and house the legions already at the camp, not to mention those still arriving each day.

Grant and Eaton resolved to put all available assets toward the refugees’ care. They commandeered deserted houses in the area to provide them shelter. And at abandoned plantations, where fields of ripe corn and cotton remained standing, Eaton employed men, women, and children older than 10 to harvest crops that, when sold, would generate funds for their own care.

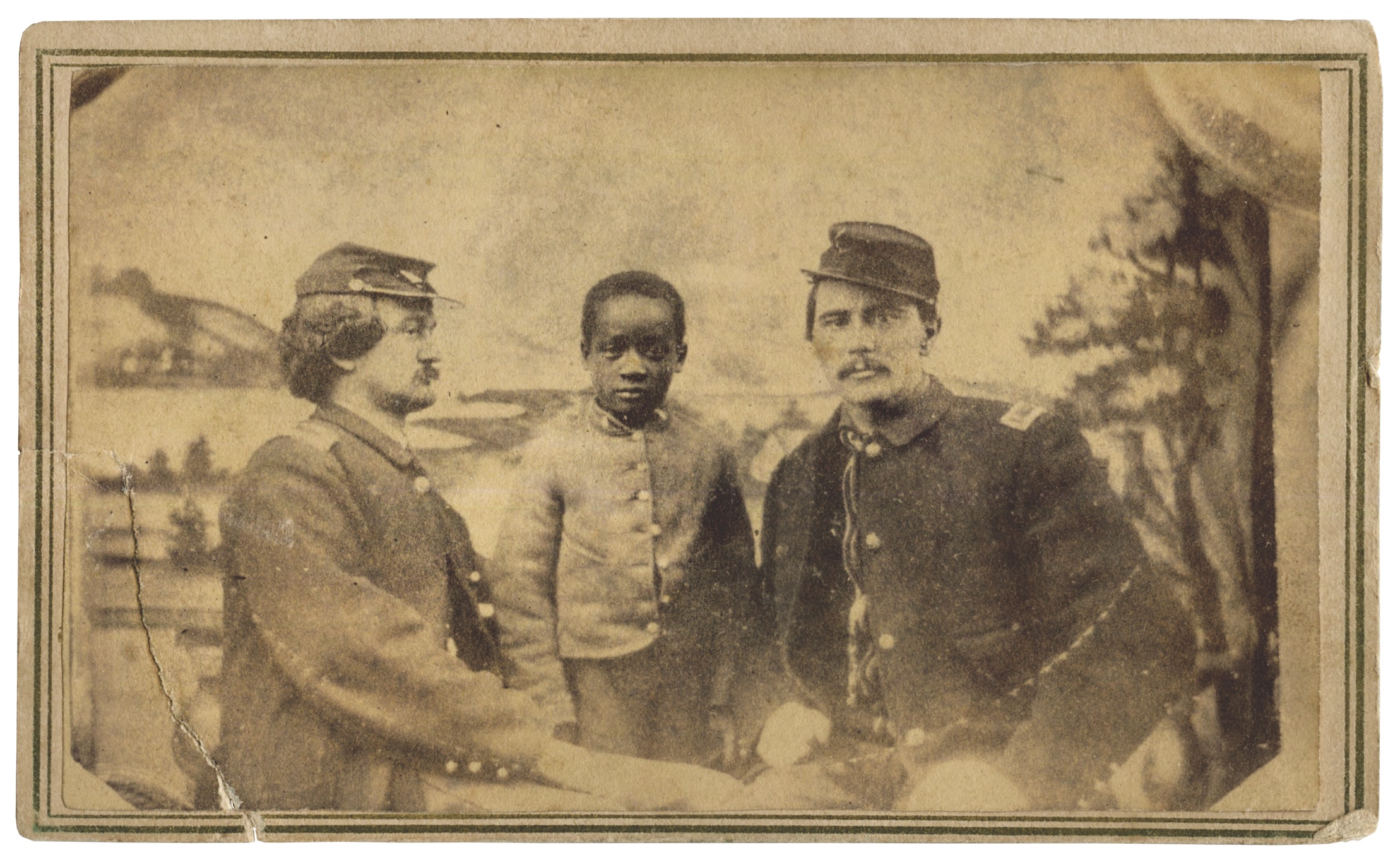

It was Grant’s hope that the contrabands, who would become known formally as “freedmen” after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued on January 1, 1863, might eventually win full citizenship. In his long-term vision, male contrabands could become soldiers and, if they fought well, it might lead to voting privileges. It was a significant first step when Adj. Gen. Lorenzo Thomas was assigned to recruit freedmen from the contraband camps for Union service and 70,000 joined from the Mississippi Valley alone.

Grant’s experience as a regimental quartermaster during the Mexican War would serve him well at this stage of the Civil War, helping him mentor Eaton in creating a military-linked organization for the refugees. Eaton rode almost daily to meet with Grant at his Hancock Hall headquarters. The two worked on establishing a system that would create soldiers and wage laborers from former slaves. They set wages for those who worked in the fields, either for the government or for planters, and a price for the cotton they harvested.

According to Grant’s order:

Commanding officers of troops will send all fugitives that come with the lines, together with teams, cooking utensils, and other baggage as they may bring with them, to Chaplain J. Eaton Jr. at Grand Junction, Tenn. One Regiment of Infantry from Brigadier-General [John] McArthur’s Division will be temporarily detailed as guard, in charge of such contrabands, and the Surgeons of Said Regiment will be charged with the care of the sick…

Grant instructed the department’s chief quartermaster to issue Eaton tools, materials for baling cotton, and clothing for men, women, and children. Grant and Eaton later joked about what might have happened if Army officials had held them accountable for the expense. “I had often enough had cause to wonder if he had ever realized this,” Eaton would write, “but my responsibilities were slight compared with those assumed by him.”

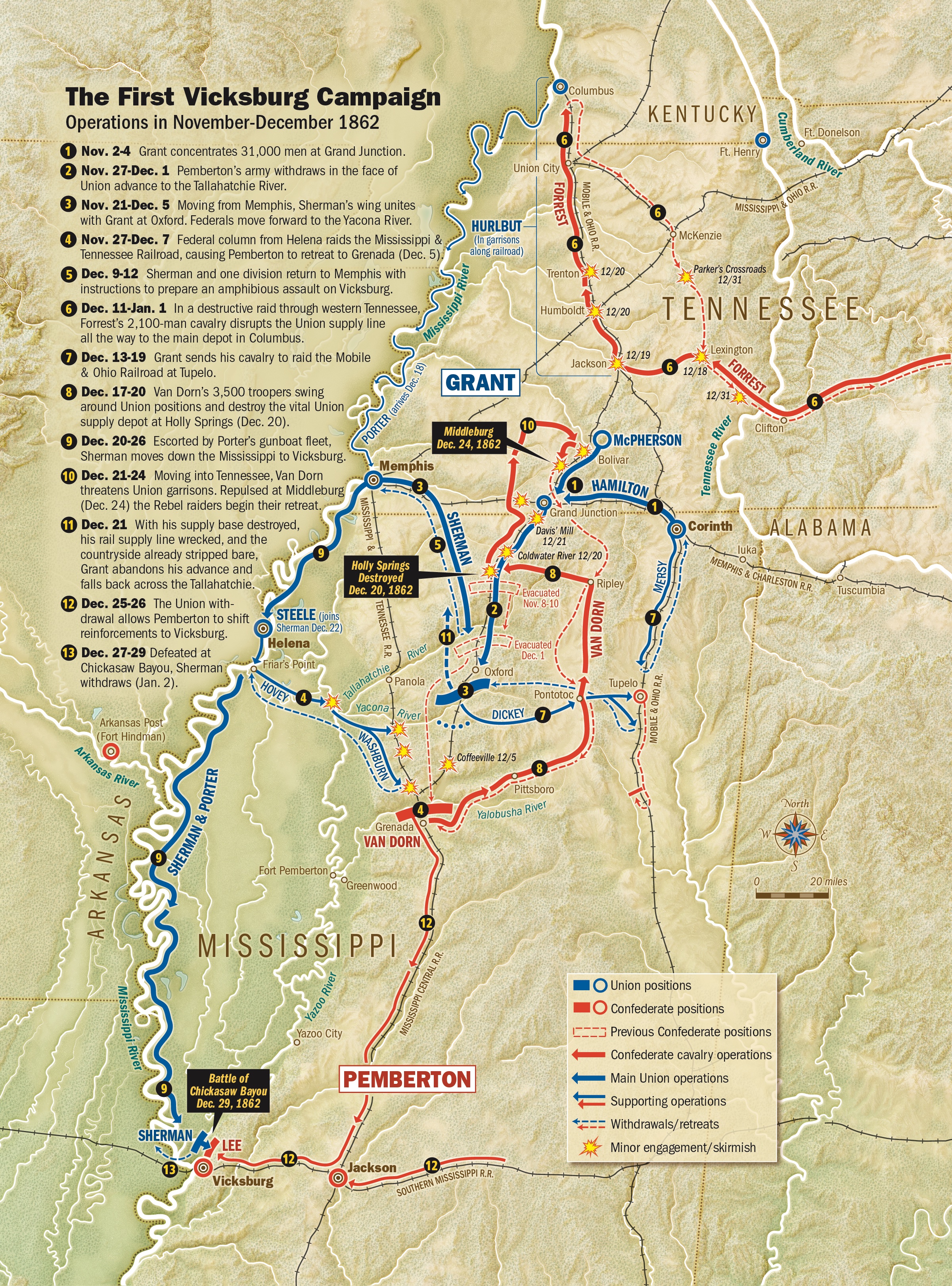

As Grant prepared to move against Vicksburg in late 1862, he moved his headquarters first to Holly Springs, Miss., site of a large Union supply depot, and then to Oxford, Miss. Eaton remained in command of the camp at Grand Junction, allowing squads of refugees under the protection of soldiers to leave each morning to gather crops of corn and cotton. Funds collected were sent to the U.S. treasurer, though Eaton found it difficult to get plantation owners to pay wages to their former slaves.

Eaton depended on Grant’s more intimate knowledge of local conditions and continued to confer with his commander in person as often as possible. They were actually together on December 20 when an early morning telegram revealed that Confederate cavalry, led by Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn, had overwhelmed the garrison at Holly Springs and destroyed $3 million in supplies.

On top of the Holly Springs raid, Grant had to deal in December and January with Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry raids into West Tennessee, which cut off Grant’s supplies and destroyed railroad tracks. Van Dorn’s and Forrest’s depredations delayed Grant’s Vicksburg Campaign for months and forced his army to pull back out of northern Mississippi to Tennessee, first to La Grange and Grand Junction and then to Memphis. He was compelled to use the Mississippi River essentially as his lone supply chain.

A key consideration for Grant during the process was the security of the contrabands at the camps in La Grange and Grand Junction. He realized that leaving the refugees behind at those camps made them easy targets of Forrest’s cavalry. The threat that Forrest’s raiders would either kill or re-enslave them was terrifying. Grant and Eaton knew those too had to be transported to Memphis.

Once the railroad tracks were repaired, troop trains were organized and the army began moving north. Each train also carried crowds of contrabands.

“[I]t was impossible to control or organize,” wrote Eaton, whom Grant had promoted to general superintendent of contrabands. “Their terror of being left behind made them swarm over the passenger and freight cars, clinging to every available space and even crouching on the roofs. The trains were moved very slowly and with the utmost caution, but even so the exposure of these people—men, women, and children was indescribable.”

In his orders promoting Eaton, Grant stressed, “In no case will Negroes be forced into the service of the Government, or be enticed away from their homes except when it becomes a military necessity.”

Within months, however, the arduous nature of the campaign began to change the general’s attitude. So did the determination of the freedmen, who volunteered in the thousands to join the Union Army.

In February 1863, a contraband camp returned to Grand Junction, where a captain in Battery F, 1st Illinois Light Artillery described the town as “mud, mud, mud. Our tent is christened Floating Palace.”

Eaton received a dismal report about the living conditions of the freedmen in April 1863. According to the report, the former slaves still lived in deserted houses and tents and were vulnerable when left unguarded “to robbery and all manner of violence dictated by the passions of the abandoned among the soldiery.” Guerrilla raids increased, one of which resulting in the death of one of Eaton’s assistants. In response, Eaton continued to leverage funds from private aid societies and expanded “life skills” training. Couples denied marriage under slavery laws were eager to be wed and many hundreds had their unions legalized.

Levi Coffin, a friend of Eaton’s, paid a visit to La Grange, where Chaplain Joel Grant of the 12th Illinois Infantry oversaw two camps and an open-air school. Coffin witnessed more arrivals, mostly women and children. There was no shelter, yet Levin said no one complained: “Their hearts were full of praise for their deliverance from slavery.”

Coffin remarked on the freed people’s extraordinary faith, quoting an older woman who arrived protected by a company of cavalry scouts: “This is the work of the Lord. I has been praying many years that He would send deliverance to us poor slaves, and my faith never failed me that he would hear my prayer, and that I would live to be free.”

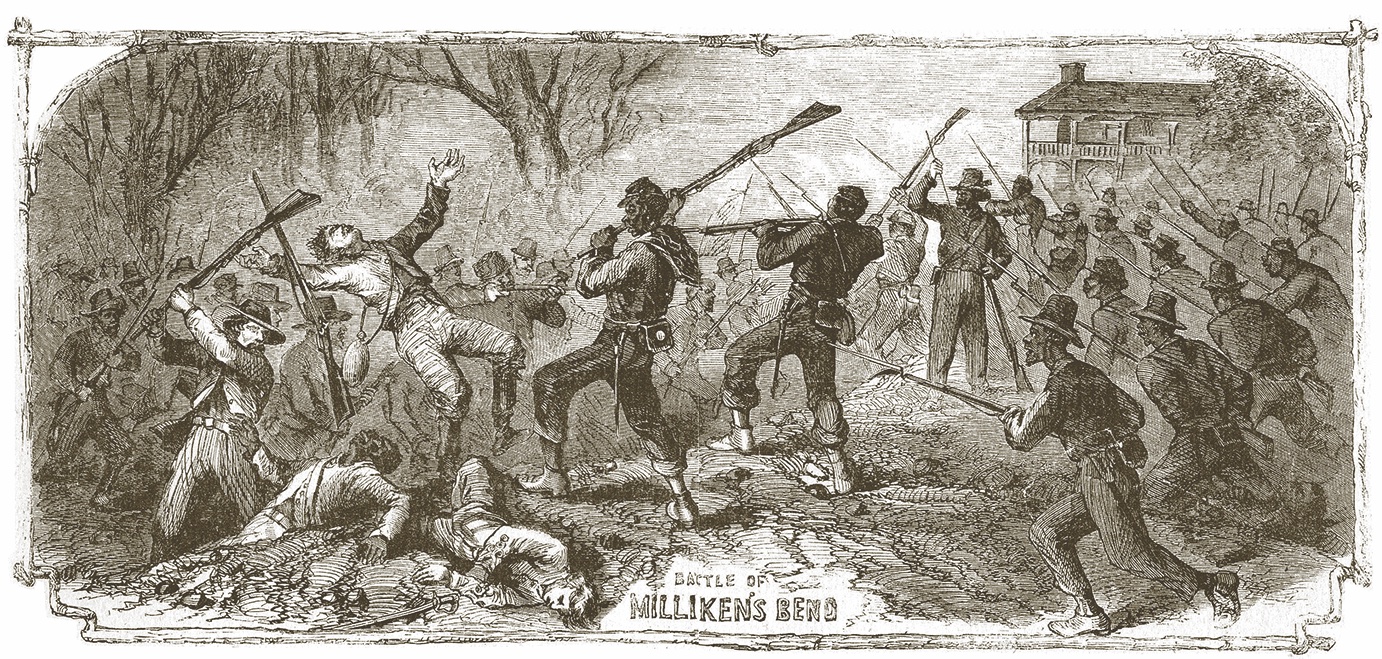

In May 1863, Grant laid siege to Vicksburg. On June 7, the Confederates attacked the Union supply base at Milliken’s Bend about 15 miles outside Vicksburg, which was guarded by the 23rd Iowa Infantry and the 9th Louisiana (African Descent), 11th Louisiana (African Descent), and 1st Mississippi (African Descent) regiments. Most of the Black soldiers had enlisted so recently they hadn’t been trained to load their firearms and had to fight with bayonets and use their rifles as clubs.

On June 8, Admiral David Dixon Porter had USS Choctaw join the fray. Artillery fire from Choctaw helped end the Confederate threat.

In his memoir, Grant, Lincoln and the Freedmen, Eaton wrote that the two-day battle was thrilling and noteworthy, opining, “there is little danger of [it] being forgotten by later generations.” He praised the Black soldiers who had “the humbler duty of safeguarding the plantations from assaults which were often vindictive and particularly cruel, and were…no less brave in their loyalty to the cause that freed them.”

Charles A. Dana, a War Department observer, wrote: “The bravery of the blacks at Milliken’s Bend completely revolutionized the sentiments of the army with regard to the employment of Negro troops.”

On a late June visit to Grant, Eaton found the general “had found time and inclination to make plans for the Negro population in and around Vicksburg.” He noted that Grant’s “willingness to lend himself and his energies to a work in one sense far removed from the great issues he was facing was nothing less than marvelous.”

There is little on Grand Junction’s landscape to mark its place in the demise of slavery. Railroad tracks still cross downtown and the southeast part of town near the Pleasant Grove Missionary Baptist Church. Unfortunately, a recent archaeological study determined that the contraband camp’s exact site remains unknown.

Grant’s and Eaton’s memories were still fresh when they met a final time in New York in 1885, as the former president lay dying of throat cancer. No longer able to talk, Grant beckoned Eaton near and wrote on a tablet, “I am very glad to see you, and wish I could have some conversation with you.” He had hoped Eaton could “say something of our use of and utilizing the Negroes down about Grand Junction….In writing on that subject for my book I had to rely on memory.” Eaton noted in his memoir that Grant recalled “the essentials of our enterprise, and reported them with surprising accuracy and completeness.”