First off, thanks to everyone for following me on this journey into the past of the Imperial Japanese Army. It’s an amazing story—a military force dragged from the feudal era into the modern world virtually overnight—and it deserves to be more widely known. As we saw last time out, the IJA stressed will and morale (where it believed it could compete with the western powers) over the material factors (where it knew that it could not). It resurrected a supposedly ancient code of behavior, bushido, as a guide to modern operations. Honor above all. Never retreat. No surrender. Death before dishonor. Given the army’s origins, the shock of its birth, the sudden realization that it had missed out on 300 years of world history, none of this is surprising. You look around, you assess your situation, and you do what you can. So the IJA was never an army that spent a lot of time adding up the material odds. If it did, it would have paralyzed itself.

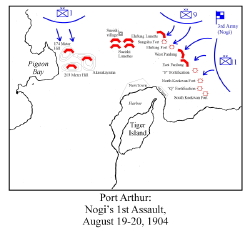

Let’s go a bit deeper, though. What does an “army of will” look like? How does it behave? How does it fight? How does a relatively small nation like Japan take on giant Russia in the war of 1904–05, for example, and triumph? We are lucky to have evidence from the army itself for this war, a memoir by a junior officer named Tadayoshi Sakurai entitled Human Bullets. To say Lieutenant Sakurai was “brave” misses the point completely. He wasn’t just brave. He actually wanted to die, he courted it, he demanded it, and he wanted every soldier in the army to do likewise. He describes soldiers weeping at not being allowed into battle. He describes a comrade actually committing ritual suicide (sepukku) to make up for the “shame” not being mobilized rapidly enough. Before every engagement, he shares the ceremonial drink of water with his comrades, the ritual of purification before death. He is eager, even frantic, in courting death, and he eventually pays the price: Russian shrapnel catches him in the first Japanese assault on Port Arthur and shatters his right arm. “Crippled and useless,” he describes himself, and yet there is a tone of satisfaction even in that grisly phrase. The book is a paean to “the Japanese ideal and determination to die in honor but never live in shame,” as he puts it.

Let’s go a bit deeper, though. What does an “army of will” look like? How does it behave? How does it fight? How does a relatively small nation like Japan take on giant Russia in the war of 1904–05, for example, and triumph? We are lucky to have evidence from the army itself for this war, a memoir by a junior officer named Tadayoshi Sakurai entitled Human Bullets. To say Lieutenant Sakurai was “brave” misses the point completely. He wasn’t just brave. He actually wanted to die, he courted it, he demanded it, and he wanted every soldier in the army to do likewise. He describes soldiers weeping at not being allowed into battle. He describes a comrade actually committing ritual suicide (sepukku) to make up for the “shame” not being mobilized rapidly enough. Before every engagement, he shares the ceremonial drink of water with his comrades, the ritual of purification before death. He is eager, even frantic, in courting death, and he eventually pays the price: Russian shrapnel catches him in the first Japanese assault on Port Arthur and shatters his right arm. “Crippled and useless,” he describes himself, and yet there is a tone of satisfaction even in that grisly phrase. The book is a paean to “the Japanese ideal and determination to die in honor but never live in shame,” as he puts it.

Even the title of the book is revealing. The Russians had superior firepower in this war. The Japanese equalizer was a willingness to charge forward no matter what the situation or odds, to be “human bullets” in the service of the emperor and to lay down their lives without a moment’s hesitation.

To which we should make two comments. First, even with human bullets scorning death and hurtling themselves against superior enemy firepower, Japan barely won this war. Indeed, the margin of victory was Tsarist Russia’s rickety political and social structure. Trying to prosecute a war and supply a mass army fighting in the empire’s Far Eastern periphery was beyond Nicholas II and his minions. Certainly they were incapable of unleashing anything like the true military potential of their sprawling empire. That would be left to a later, much more ruthless Communist regime. By 1905 revolution had engulfed Russia, and the Tsar had no option but to open peace talks.

We sometimes forget, however, that the Japanese, too, were exhausted by this point. They had fired off their entire arsenal of men and materiel, their field logistics were atrocious, and the treasury was bankrupt. The Russo-Japanese War was a victory, yes, but the margin was much narrower than the Japanese were willing to admit.

Second, let’s be honest about what actually happened at the front. Despite Sakurai’s extravagant claims, how many of those hapless Japanese conscripts throwing themselves against the Port Arthur fortifications really wanted to be human bullets? We know today that there were more than a few regiments that simply refused what they viewed as their officers’ senseless orders to attack enemy machine guns. And yes, despite the mythology, this war featured Japanese soldiers surrendering repeatedly. In modern combat, when your unit suddenly finds itself cut off without hope of relief, it happens. While the Japanese triumphed over Russia in this war, they didn’t suddenly reverse the laws of modern military physics. They weren’t supermen, and they died like any other soldiers when you shot them. Moreover, responsible commanders at the front recognized the problem, and protested to their superiors about the nonsensical infantry doctrine they were called upon to implement. There were also repeated protests among the civilian population once the needlessly high Japanese casualty statistics became public knowledge.

The army’s high command and government dwelt on none of these unpleas-antries, however. As far as the generals were concerned, a win was a win. They preferred to talk about the soldiers who carried out suicidal attacks, or who killed themselves rather than surrender, or who died with the words “Port Arthur” on their lips. These heroes were declared “war gods” (a new concept in Japan) and held up as examples for young Japanese boys to emulate. In the wake of the victory over Russia, it was fairly simple to silence contrary voices and doubters.

I admit, I’m ambivalent. There are times when I read Human Bullets and I respond to it. How wonderful, I think, to love your country so dearly! What an awesome and mysterious thing it must be to make that supreme sacrifice! Dulce et decorum est.

But there are many other times that I read Sakurai, urging the youth of Japan to follow his example, to have their limbs blown off and their bodies shattered and to die in senseless military adventures, and I want to resurrect him solely for the purpose of trying him as a war criminal.

More next time.

For the latest in military history from World War II‘s sister publications visit HistoryNet.com.