Shocked by American racism, Caribbean immigrant pushed education and self-empowerment

CAMEO

LANGSTON HUGHES ENTHUSED about “Haitian Harlem, Cuban Harlem, little pockets of tropical dreams in alien tongues. Magnet Harlem…Melting pot Harlem—Harlem of honey and chocolate and caramel and rum and vinegar and lemon and lime and gall.” In 1920, a third of New York City’s black residents, most of whom lived in Harlem, had been born in the Caribbean. These immigrant ranks included a brazen purveyor of candor and gall: the brilliant editor, activist, educator and orator Hubert Harrison. Now all but forgotten, Harrison and his strivings are a compelling American story. Fondly known as “the Black Socrates,” he ran newspapers and political organizations, fostered activists and artists, decried racial injustice in articles and essays, called out black leaders for toadying to white patrons or espousing elitism—he scorned W.E.B. DuBois’s “Talented Tenth” as the “Subsidized Sixth”—and courageously pushed an agenda of black education and empowerment. The Voice, a weekly he founded in 1917, had a reach estimated at 55,000 at a time when New York City was home to 60,000 African Americans. Harrison collected and traded books. He lectured on street corners and from podiums on topics from Tennyson’s poetry to the “World Problems of Race” and memorialized his love life in Latin. Buried in an unmarked grave in the Bronx, he led a remarkable life Jeffrey Perry chronicled in 2009’s Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883—1918.

[divider_flat]Born in 1883 in St. Croix, the Virgin Islands, then a Danish colony, Hubert Harrison grew up in extremely modest circumstances. After his mother died in 1900, he emigrated to New York City, soon moving to Harlem. He got a night school secondary diploma but no more formal training—except from his formidable self, augmented by self-confidence forged in the West Indies amid a history of slave rebellion, labor protest, and marginal white hegemony. In St. Croix, literacy was high and residents of African or mixed descent often had middle-class jobs. Life in the States, with its epidemic lynchings, Jim Crow, and disenfranchisement of black voters, profoundly shocked these transplants, Harrison included. He stood apart with his bold push for equal rights.

Eventually he married and landed a good position with the U.S. Postal Service. Children and marital trouble ensued. In 1910, challenging Booker T. Washington’s assertions about opportunities for blacks in the South, he published a letter in the New York Sun rebutting Washington’s optimism with hard data on harsh racial disparities. Allies of Washington at the Post Office claimed Harrison was a slacker; he lost his job. Thereafter he always struggled. Among his papers are notes he made for a book review penned on the back of a final rent’s-due notice.

In 1911, Harrison joined the Socialist Party. He worked for two years as an organizer and was the only black speaker to address the Paterson Silk Strike in 1913, when workers seeking an eight-hour day and better conditions walked out of a New Jersey fabric mill. He deeply impressed novelist Henry Miller, then a young socialist. “With a few well-directed words he had the ability to demolish any opponent,” Miller later recalled. “He did it neatly and smoothly too, `with kid gloves,’ so to speak. I described the wonderful way he smiled, his easy assurance, the great sculptured head which he carried on his shoulders like a lion . . .”

But Harrison soured on the Socialists, who hesitated to organize blacks, and provided only desultory support. American entry into World War I drove him to embrace a strategy aroused by President Woodrow Wilson’s rhetoric about fighting for democracy. For Harrison that soaring talk contrasted painfully with the reality of denial of the vote and other basic civil rights to 12 million black Americans.

In 1917, Harrison started The Voice, a broadsheet advocating black empowerment and debate but also carrying book reviews and poetry. Printed on pink paper recognizable even to illiterates, the paper enjoyed enormous success—but Harrison refused to carry ads for skin lighteners and hair straighteners, and his revenues shrank. In 1918 he created the Liberty League to champion federal anti-lynching legislation and urge black solidarity and self-defense—if necessary, armed. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People avoided such militancy, preferring an anti-lynching public relations campaign, the type of tepid advocacy that caused Harrison to inveigh against fellow blacks with “a wish-bone where their backbone ought to have been.” No anti-noose bill passed; even today, a lynching ban put forth by Senators Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), Kamala Harris (D-California), and Tim Scott (R-South Carolina) may stall in Congress.

Struggling in 1918 with health problems, Harrison eventually had to shutter The Voice. In summer 1919, race-based violence gripped the United States as black war veterans refused to resume the status of second-class citizen. In response white mobs rampaged in Washington, DC, Houston, Chicago, St. Louis, Omaha, and Tulsa. The bloody season’s death toll reached some 1,000 blacks and whites. In an October 1919 edition of New Negro, a short-lived monthly magazine, Harrison wrote, “The great World War, by virtue of its great advertising

campaign for democracy, and the promises which were held out to all subject peoples, fertilized the Race Consciousness of the Negro people into the stage of conflict with the dominant white idea of the Color Line. They took democracy at its face value, which is—Equality. So did the Hindus, Egyptians and West Indians. This is what the hypocritical advertisers of democracy had not bargained for. The American Negroes, like the other darker peoples, are presenting their checques and trying to ‘cash in,’ and delays in that process, however unavoidable to the paying tellers, are bound to beget a plentiful lack of belief in either their intention or their ability to pay. Hence the run on Democracy’s bank—’the Negro unrest’ of the newspaper paragraphers.”

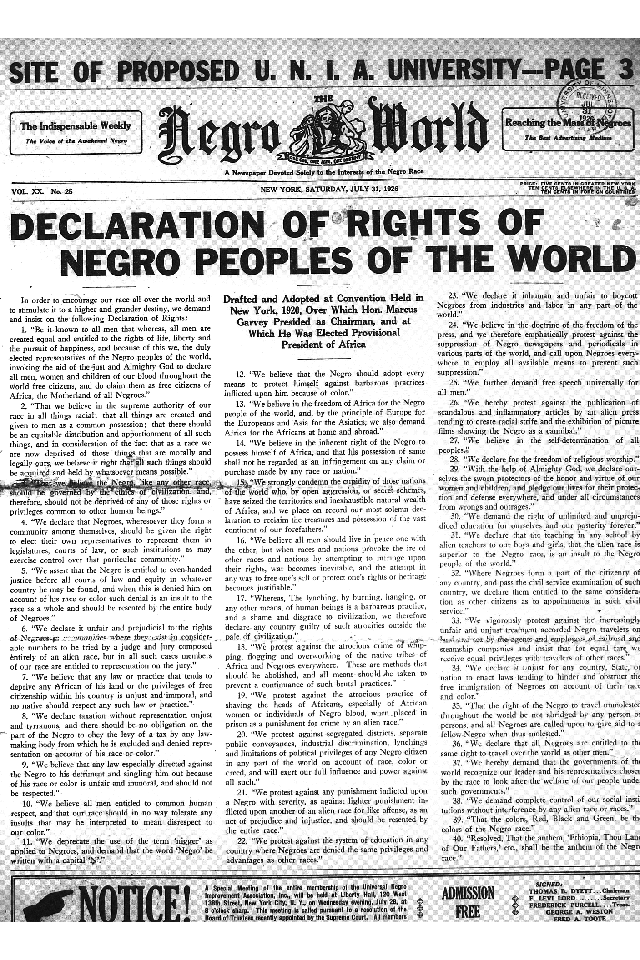

In 1920, Harrison briefly edited Negro World, a weekly published by Jamaican immigrant and Harrison emulator Marcus Garvey, before tiring of working for Garvey. He became an American citizen in 1922, supporting himself giving lectures stressing the value of education. “Remember always that the best college is that on your bookshelf,” he told listeners. “The best education is that on the inside of your head.” Harrison spelled out his commitment to free thought in a 1923 rhyme, “Caliban Considers”:

“They are slaves who dare not choose

Hatred, scoffing and abuse,

Rather than in silence shrink

From the truth they needs must think

They are slaves who dare not be

In the right with two or three.”

In 1924 Harrison established the Liberty Party, which focused on international black political organization. Its founder avoided the limelight.

Struck by appendicitis in 1927, Harrison, 43, died in surgery. On many fronts in his own life stymied, he pioneered the creed of black self-determination taken up by the flamboyant, flawed Garvey and, decades later, Malcolm X. In practical terms, Harrison’s ideas about black mobilization were tested by an early socialist colleague. A. Philip Randolph went on to head the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the most effective black union in American history. In 1941, with war looming, Randolph’s power as a union boss and political leader forced President Franklin Roosevelt to desegregate the defense industry. In 1963 Randolph marshaled blacks to march on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in a mass call for jobs and civil rights that indirectly echoed the long-dead Harrison, whose intensity had included a vivid sense of humor. Conjuring his late friend’s laughter, Jamaican poet Claude McKay recalled how Harrison “exploded in a large, sugary black African way, which sounded like the rustling of dry bamboo leaves agitated by the wind.”