[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n the afternoon of June 24, 1944, a messenger from the Marines’ V Amphibious Corps headquarters entered the frontline command post of the Army’s 27th Infantry Division on Saipan and handed a message to Major General Ralph C. Smith. Smith read the message, pocketed it without comment, and returned to the task at hand—the battle raging just outside his tent. For several days, two of his regiments had conducted fruitless frontal assaults on Japanese positions along areas the soldiers had christened Purple Heart Ridge and Death Valley, with little to show for their efforts besides casualties. The delay was holding up the larger corps attack, a fact that had been pointed out to Smith—a tall, quiet man of 50 with the demeanor of the academic he later became—in a terse telegram from the corps commander earlier that day. To get his division moving again, Smith planned to halt the frontal attacks and start launching aggressive flanking actions the next morning.

He visited his forward positions and returned to his division headquarters to find Major General Sanderford Jarman waiting for him. Smith gave Jarman a detailed briefing of the current situation and went over his plans for the flanking attacks in minute detail. He then called his officers together and told them what he’d known since receiving the message earlier that afternoon: he had been relieved of command, and Jarman was taking over.

Smith and Jarman continued their conversation well into the night, breaking off only when a second message arrived ordering Smith to pack his personal belongings and be on a Hawaii-bound plane before daybreak. He left Saipan without being allowed to say goodbye to the officers and men he had led for over 18 months through three bloody battles.

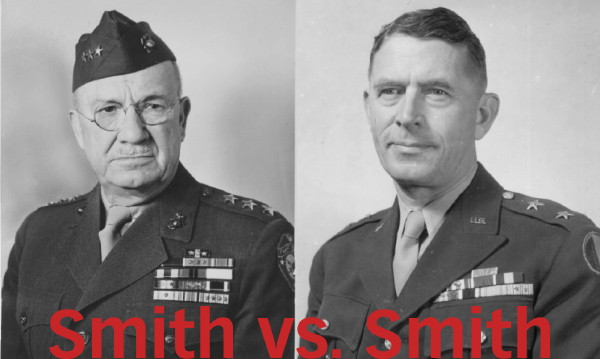

During that time, Ralph Smith had had a strained relationship with the Marine V Corps’ commander, Lieutenant General Holland Smith. Almost from the beginning of their acquaintance, Holland Smith, a jowly bulldog of a man in his early 60s, was openly contemptuous of the abilities of the Army in general—and of the 27th Division and Ralph Smith in particular.

The tensions that erupted at Saipan didn’t originate there, but resulted from the opening of wounds the two services had barely patched over since World War I. Many Army officers, for example, still resented the Marines for receiving what seemed like an outsized share of praise after the 1918 Battle of Belleau Wood. As for the Marines, there was a perpetual—and well-founded—fear that the Army was scheming to absorb the Corps into its own structure.

Nonetheless, all involved assumed that Ralph Smith’s relief from duty would be accepted as little more than a routine wartime shuffling of commanders. After all, three other Army division commanders had been relieved in the Pacific Theater—two of them by naval commanders—without threatening service relations. Instead, Smith’s relief became the opening salvo of a battle that raged through the remainder of the war and beyond.

The two men at the center of the controversy were a study in contrasts.

Lieutenant General Holland McTyeire Smith prided himself on his ability to relate to the common Marine. Despite a privileged upbringing in Alabama, he eschewed the trappings of rank, preferring to wear a combat uniform rather than dress whites.

As had been expected of him, Holland followed his father, a prominent lawyer, into law, joining his firm immediately after law school. But the venture was short-lived; by his own admission he was a terrible lawyer and lost the few cases he handled. After a year he decided to follow his true love: the military, joining the Alabama National Guard, then winning a commission in the Marine Corps in 1904.

His Marine career took him all over the world. Although he was often under fire, it was as a staff officer, not as a commander—something that ate at him as the years passed. Along the way, Holland picked up the nickname “Howlin’ Mad” for his short temper, which exploded regularly, especially when he perceived any slight against “his” Marines.

Certainly his greatest strength—and weakness—was his complete inability to compromise where his Marines were concerned. While rank-and-file Marines appreciated his efforts, many of his contemporaries viewed his combativeness as misguided and counterproductive. But while some were surprised at his rise through the ranks, his superiors apparently were not among them. Holland was chosen as one of only six Marines to attend the Army Staff College, then the Naval War College, and finally became the first Marine on the Joint Army-Navy Planning Committee. By 1939 he was the Deputy Commandant of the Marine Corps. But his most important contributions were yet to come.

In late 1939 he took command of the 1st Marine Brigade, which eventually became the 1st Marine Division, at Quantico, Virginia. Soon he would be given command of the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet, followed by the Amphibious Corps, Pacific Fleet. Under his exacting eye, the Marines developed and perfected their amphibious doctrine—the Marines’ main raison d’être since the end of World War I. Not only was Holland instrumental in developing this doctrine and the supporting equipment, he personally oversaw the training of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Marine Divisions as well as the 1st, 7th, 9th, 77th, 81st, and 96th Army Divisions.

But he still lacked the thing he desired most: a combat command. He was devastated when command of the 1st Marine Division for the Guadalcanal Campaign, the first great offensive of the Pacific War, went to Major General Alexander Vandergrift. One after another he was passed over for command of each deploying combat division. He began to suspect that he had enemies in high places, but the simple matter was that Holland was almost 60 years old and division commands were going to younger men. Even when Admiral Ernest King placed him in command of the new V Amphibious Corps, the amphibious landing force in the Central Pacific, he continued to believe that the Army and Navy were conspiring to keep him and his Marines from their rightful share of glory.

Less is known about his antagonist, Ralph Smith, simply because he was not one to talk about himself. Unlike Holland Smith, Ralph was known for his calm demeanor. His operations officer once said of him, “I have never, ever seen him angry….As a matter of fact, I don’t recall the Old Man ever saying even a ‘god damn.’”

Ralph Smith’s quiet demeanor belied an adventurous life. He had been taught to fly by Orville Wright himself, and received the 13th pilot’s license ever issued. After a stint in the Colorado National Guard, Lieutenant Smith joined General John Pershing’s punitive expedition against Pancho Villa on the Mexican border and then served under Pershing again in World War I, where he received two silver stars for bravery and was wounded at the Battle of Meuse-Argonne.

Ralph Smith was also an intellectual. He spoke fluent French and was a graduate of the Sorbonne as well as the American War College and the French École de Guerre. In fact, a report he wrote on the École caught the attention of General George Marshall, who personally picked him to serve on the G-2 intelligence staff, where he assisted in the rapid expansion of intelligence services.

It would seem logical that an officer regarded as one of the foremost experts on France and the French military would get command of a division destined for the European Theater. Instead, the Army placed him in command of the 27th National Guard division, then in Hawaii—and directly on the path to controversy.

As the 27th began training for the invasion of the Gilbert Islands—the first leg of the island-hopping campaign through the Central Pacific, set for November 1943—Ralph became concerned about the competence of his subordinate commanders. On top of that, it quickly became apparent that months of manning defensive positions in Hawaii had dulled his division’s fighting edge. Fixing these problems proved a slow process. Many of the unit’s officers resented an outsider being given command of “their” division. Furthermore, it was Ralph’s practice to never dismiss subordinates without ample cause, feeling it was unfair to prejudge his officers without giving them a chance to prove themselves in combat. This trait was at the root of problems to come; Ralph’s “extreme consideration for all other mortals,” as a lifelong friend observed, “would keep him from being rated among the great captains.”

The two Smiths first encountered one another during the planning for the invasion of the Gilberts, soon after Ralph Smith took command. The 2nd Marine Division, under another General Smith—Major General Julian Smith—was to attack Tarawa, while the 27th Division’s 165th Regiment would attack the more lightly defended Makin Atoll, with both invasions scheduled to take place simultaneously on November 20, 1943. Holland Smith’s role was limited to training and administration; despite the title of corps commander, he never actually commanded anything during the Gilbert operations. Instead, orders passed directly from Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the commander of the naval transport and support element of the operation, to the respective landing force commanders—Julian Smith and Ralph Smith.

To add to the perceived insult, since Holland Smith was not in the tactical chain of command, he was relegated to a ship off the coast of Makin. Left impotent while his beloved Marines were being slaughtered on Tarawa, and unable to strike at any of his superiors, he turned his frustration and anger on the 27th Division and Major General Ralph Smith.

Although it took the same amount of time to secure Makin as it did Tarawa—three days—in Holland’s mind, this was far too long for an island he considered barely defended. In fact, he later claimed, based on the Marine operations on Eniwetok, that the Army should have been able to secure the island in seven hours. It was a charge he would repeat throughout the war and beyond. While it was true that Makin was a much easier nut to crack than Tarawa, there were several important facts Holland failed to consider.

First, many of the Marines on Tarawa were Guadalcanal veterans, while the soldiers of the 165th were facing combat for the first time and thus naturally more cautious. Second, the number of enemy on Makin was far higher than the 250 Holland had assumed; in fact, there were some 750. Additionally, Makin was covered in thick jungle, unlike the sparser terrain of Tarawa, making movement much slower.

Most significantly, Holland failed to take into account that the Army approach to warfare was very different from that of the Marines. Army ground forces were accustomed to much slower, deliberate operations utilizing all aspects of combined arms and avoiding frontal assaults. That made sense since the Army’s mission included lengthy ground campaigns. The Marines, on the other hand, were created as an assault force. Their mission was to land, smash the enemy’s defenses, and get out. The Marine theory was that a unit might take more casualties in the early stages of the fight, but by avoiding a protracted campaign, where the enemy might regroup and counterattack, losses could be contained to an acceptable level.

Neither approach was superior; they just reflected different service cultures and the different circumstances under which the two forces were meant to be deployed. This tension had been reflected in Holland’s initial criticism of the Army’s plan, which he had derided as needlessly complicated. While the Marines planned to go straight across Tarawa’s beach into the enemy stronghold, the Army planned a two-pronged landing on Makin to pinch the enemy flanks.

Holland Smith vented to his staff and to reporters that the Army’s slowness had kept him from going to Tarawa—conveniently overlooking the fact that Admiral Turner had not given him permission to land there. Holland’s rage at the Army for its perceived missteps reached a boiling point the morning after the last day of the battle—November 24, 1943—when a Japanese submarine just off Makin sank the escort carrier Liscome Bay, killing more than 700 sailors. In his mind, the 27th had the sailors’ blood on their hands: if the division had moved more quickly, the Liscome Bay would have been long gone and safe. A more extreme example of the bitterness with which he had come to regard Ralph Smith’s unit came in an accusation he made shortly afterward to his staff: that the 165th allowed the body of its commander, Colonel Gardiner Conroy, to lie within view of the enemy for three days because the men were too scared to recover it. (He continued to perpetuate this story after the war, although the unit diary and an affidavit by the division chaplain clearly indicate that the body was recovered within an hour and buried within 24 hours.)

If ever there was a time for Ralph Smith to rise in a loud and vociferous defense of his men, this was it. But being disrespectful was not in his nature. Besides, as he later said, Holland’s rantings did not affect the mission, so he saw no need to respond in kind.

The undercurrent of interservice differences—and the fury they provoked in Holland—was mitigated somewhat during the operations in the Gilbert Islands, and the operations in the Marshalls that followed. In those campaigns, the Army and Marine Corps were deployed in parallel operations on separate islands, the battles were over in a matter of days, and Holland Smith did not have operational command after the landings. All that changed on Saipan.

On Saipan, the size of both the island and the Japanese garrison meant that operations would last for weeks rather than days and involve several divisions. For that reason, Holland would land on the island and, for the first time, function as a true tactical commander. Saipan would also mark the first time since Guadalcanal that Army and Marine forces would conduct operations on the same terrain. This time, the 27th Division would be in reserve, with two Marine divisions (2nd and 4th) conducting the initial landings on June 15.

The 27th landed the next day, and immediately went into action, capturing the Aslito Airfield and joining an eastward sweep, with the 4th Marine Division in the north, the 27th in the center, and the 2nd Marine Division in the south. But as the advance moved steadily across to Nafutan Point, the 27th fell behind—the result of more difficult terrain, higher-than-anticipated enemy resistance, and an unwillingness to bypass enemy strongholds as the Marines did. This caused the line to bow into a U, forcing the Marines to wait until the Army caught up. Holland fumed about the Army’s slow pace, exclaiming to his staff, “The 27th won’t fight and Ralph Smith will not make them fight!”

Things came to a head starting on June 21, when Holland ordered Ralph Smith to leave a battalion to mop up the remaining Japanese at Nafutan Point, while using the rest of the division in a northward sweep. Holland did not specify where the battalion should come from, but because he and Ralph had previously discussed using the 105th Regimental Combat Team for mopping up operations, Ralph ordered its 2nd Battalion to undertake the mission, even though it was in the corps’ reserve and therefore under Holland Smith’s command. Then, as if to underscore the slow pace of the 27th, the unit was an hour late in launching an attack on June 23, which in turn kept the Marine units on either side from attacking on time.

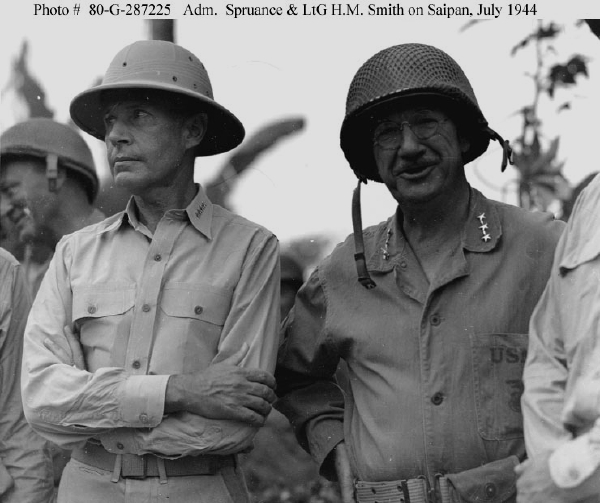

Holland had had enough. He visited Admirals Turner and Raymond Spruance seeking permission to relieve Ralph Smith from command. Thinking a change of leadership would get the 27th Division moving again, Spruance approved the request.

At the time, no one was angrier about Ralph Smith getting sacked than Lieutenant General Robert Richardson, the commander of Army forces in the Pacific. Like Holland Smith, he was hyper-partisan, obsessed with ensuring the Army received its proper share of recognition in the Central Pacific. In fact, it was Richardson who campaigned vigorously against the Marines getting any command above division level early in the war. And it was Richardson who threw fuel on the fire of the Smith vs. Smith controversy.

On July 4, while Americans were still fighting on Saipan, Richardson convened a board of inquiry into Ralph Smith’s relief. The board was headed by Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner, who limited testimony to only Army officers and official records. Unsurprisingly, the board found that although Holland had the authority to relieve Ralph Smith, the relief was not justified and should not adversely affect Ralph Smith’s career.

Then, a week after hostilities on Saipan ended, Richardson landed on Saipan and—without authority or permission—presented commendations to the 27th Division. This was a breathtaking breach of military etiquette. His actions were clearly designed to send a message to Holland about how the Army viewed the 27th’s performance. It was a blatant enough insult that Admirals Turner and Spruance both complained to Admiral Nimitz about Richardson’s actions.

None of this diminished the Army’s anger over Ralph Smith’s relief from duty. Service relations became so strained that several Army commanders (Ralph Smith’s replacements, Major Generals Sanderford Jarman and—after him—George Griner included) wrote letters to the Buckner Board stating that Army units should never serve under Holland Smith again. It was especially significant that Jarman, who initially agreed with Holland about the lack of aggressiveness in the 27th, soon believed that Holland was too prejudiced to make an impartial assessment of any Army unit.

Back in Washington, General George Marshall and Admiral Ernest King expressed concern that relations between the two services had deteriorated beyond normal rivalry. They decided not to take official action, hoping the controversy would die on its own.

It was left to the media to pick up the fight, which it did almost as soon as the battle on Saipan finished. On July 8, 1944, the San Francisco Examiner, a Hearst publication, castigated Holland Smith as a butcher who measured fighting spirit by casualty numbers. In response, Time and Life magazines—led by correspondent Robert Sherrod, who had landed with the Marines at Tarawa and Saipan (and later Iwo Jima)—took the Marines’ side. Sherrod claimed that the 27th had “frozen in their foxholes” and had to be rescued by the Marines. Moreover, he asserted that the final Japanese banzai attack on July 7, during which 3,000–4,000 Japanese had attacked two Army battalions, had only been stopped by a Marine artillery battalion.

But the reality was the battle had raged for a full day and, in the end, the 27th suffered more than 400 killed and 500 wounded against a confirmed 4,311 enemy dead. Only about 300 Japanese casualties were in the Marine sector.

When Admiral Nimitz, in response to his articles, recommended that Sherrod’s credentials as a war correspondent be revoked, Holland’s long friendship with the admiral began to crumble. Holland saw it as a personal betrayal and a rebuke of his actions—a belief reinforced when Nimitz marked Holland as only “fair” in the loyalty section of his fitness report. Perhaps most galling, when planning began for the landings at Okinawa, Tenth Army was given to the man who had exonerated Ralph Smith—Simon Bolivar Buckner—while Holland was moved out of the combat zone. Afterward, Holland blamed Marine casualties on poor Navy support and accused Nimitz of riding to fame on the shoulders of the Marines. The crowning insult—and a sure sign that Holland Smith was on the outs with those who counted most—came when Douglas MacArthur, with Nimitz’s consent, refused to invite Holland to witness the surrender of the Japanese—a surrender that was Holland’s victory as much as MacArthur’s.

Still, the conflict surrounding Ralph Smith’s relief from duty might have been relegated to the past more quickly if not for one man: Holland Smith.

Holland began his memoirs, Coral and Brass, in 1946—after he retired and received his fourth star—intending to settle scores. Published in 1949, the book took aim at everyone who had ever crossed him or his beloved Marines. His version of events was so twisted that after reviewing a draft of it, Marine Commandant Clifton Cates, Secretary of Defense James Forrestal, and Secretary of the Navy John Sullivan had urged him not to publish it. These men had just completed the acrimonious unification battle following the war, during which the Army had proposed curtailing or outright eliminating the Marine Corps. They had no desire to fire up a cooling controversy. Even Holland’s most vociferous defender, Robert Sherrod, had refused to coauthor the book, and attempted to get Holland to tone down some of his accusations and correct historical inaccuracies before publication.

The Army’s leadership was unsurprised by Holland’s version of events, but senior Navy officers felt betrayed, especially by Holland’s claims that he had fought against the Tarawa landings from the beginning, when, in fact, he not only helped plan the operation, but defended it as necessary at the time. They issued public statements denying his claims, without making any direct attacks on the man. In private letters, however, several admirals questioned Holland’s stability and his motives for publishing a book filled with such easily disproved fallacies. Admiral Harry Hill, who had worked closely with Holland on many landings, threatened to sue him if certain statements attributed to him were not removed from the book before it went to press. He also sent a note to Admiral Turner lamenting, “Poor old Holland…I hate to see him throw away what he gained in his whole career just for the sake of getting all of this off of his chest…he was a very bitter individual.” Ed Love, the 27th Division historian, took such offense to the book that he wrote a point-by-point rebuttal, published in the Saturday Evening Post and Infantry Journal.

The only person who refrained from commenting was Ralph Smith. Happily retired and settled into a second career in academe as a fellow at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace, he never once publicly commented on Holland Smith or on being relieved of command. Even when Holland died in 1967, Ralph remained silent. It was not until 1986 that he agreed to speak to historian Harry Gailey—not to exonerate himself, but to defend the courage and competence of his soldiers.

Until his death in 1998 at the age of 104, Ralph remained the stoic he had always been, believing that his actions would speak for themselves. While some have admired his ability to remain above the fray, his silence allowed Holland’s version of events to stand unchallenged long enough to become accepted as the truth by many.

It is hard to imagine that an event that barely registers today as more than a footnote to the Pacific War actually dominated the news and threatened the success of operations at the time. But its influence went well beyond World War II. The incident continued to taint Army-Marine relations through Korea and even Vietnam, as the young men of World War II rose to command in their respective services. In both of these conflicts, the Army went to great lengths to avoid having Army soldiers serve under Marine commanders, and to prohibit Marines from commanding above division level. It was not until the 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act mandated the creation of joint commands and doctrine, with leadership of the major commands now moving between the services, that interservice rivalries began to abate—assisted by the rise of a new set of senior commanders who had no vested interest in a dispute 40 years in the past. Further proof of the end of this controversy is the almost 10 years of war in Afghanistan and Iraq, during which combatants have served seamlessly under both Army and Marine commanders with few issues. More than 60 years later, this ghost of Saipan has finally been laid to rest.

Sharon Tosi Lacey is a graduate of the United States Military Academy, and currently serves as a lieutenant colonel on the U.S. Army Staff. She is writing her dissertation for Leeds University on joint Army-Marine operations in the Central Pacific.