In late April 1945, the world was on edge. And in a single 24-hour period, April 29–30, two momentous pieces of news broke. From a conference in San Francisco, the Associated Press posted a story that the Germans had surrendered unconditionally. And news sources worldwide reported that in Berlin Adolf Hitler had died by his own hand.

Hitler was dead. But the war in Europe was not over. Still, the AP report had hustled President Harry S. Truman out of Blair House and across Pennsylvania Avenue to the White House to confirm the claim. The man who should have known whether the Germans had surrendered, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, was in his bedroom in Reims, France, about to turn in for the night. And the man at Reims whose job it was to confirm the AP claim, Stars and Stripes reporter Charles F. Kiley, 31, was in his billet near Eisenhower’s quarters and the red brick technical school that had become Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) headquarters.

Kiley, a U.S. Army staff sergeant, was the pool reporter shadowing Eisenhower on behalf of the world’s press—with the European campaign speeding to a close, an assignment that could make a career. But with Kiley and the Supreme Commander in France, where it was 3 a.m., confirming the story was a strange task. Had the Germans surrendered in San Francisco? Dick Underwood, copilot of Eisenhower’s plane, grabbed the general’s jeep, collected Kiley, and motored to Ike’s quarters. The general did not know of the San Francisco report, although he had heard of an earlier dispatch stating that Heinrich Himmler had offered to surrender to the U.S. and Britain, but not to Russia. An aide of Eisenhower put through a call to 10 Downing Street in London, and Kiley and Underwood stood by in silence as the general lit a cigarette, offered the two men smokes, and waited to speak with Winston Churchill.

There was nothing to it. The AP story was false. Kiley described Eisenhower’s reaction in a letter to his wife Billee the next morning. “Frankly, darling, he was a little perplexed,” Kiley wrote, adding that Eisenhower remarked to the men that it “‘would be an ironic climax to this war if it was over and I didn’t know about it.’” Kiley felt the same. He had drawn the assignment to cover the big finish: what if a wire reporter 6,000 miles away scooped him?

from private to newsman

Charles Kiley was my father. As a child, I had pored through the 10 volumes of Stars and Stripes my uncle had had bound, gently turning the yellowing pages and asking Dad all I could about stories with his byline. I listened to the tales he and his Stripes friends told, and later read the voluminous correspondence between him and my mother—all told, more than 800 letters. And in his last year of life I spent most of a month at his bedside, interrupting his depression over the broken leg that had landed him in a nursing home by saying, “Tell me about that time when you were in France with Eisenhower,” or “Tell me what it was like to put out that paper on Utah Beach.”’

Charles Kiley was no stranger to history or to celebrity. As a sportswriter for the Jersey Journal in Jersey City, New Jersey, he had covered Babe Ruth up close and been in the Yankee locker room. He had reported on Joe Louis’s 1936 and 1938 fights against German Max Schmeling at Yankee Stadium. But when he was drafted into the army in November 1941 and set out for basic training at Camp Croft in Spartanburg, South Carolina, as a buck private with the 26th Infantry Training Battalion, he hardly could have pictured himself standing in General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s bedroom while the Supreme Commander phoned Winston Churchill.

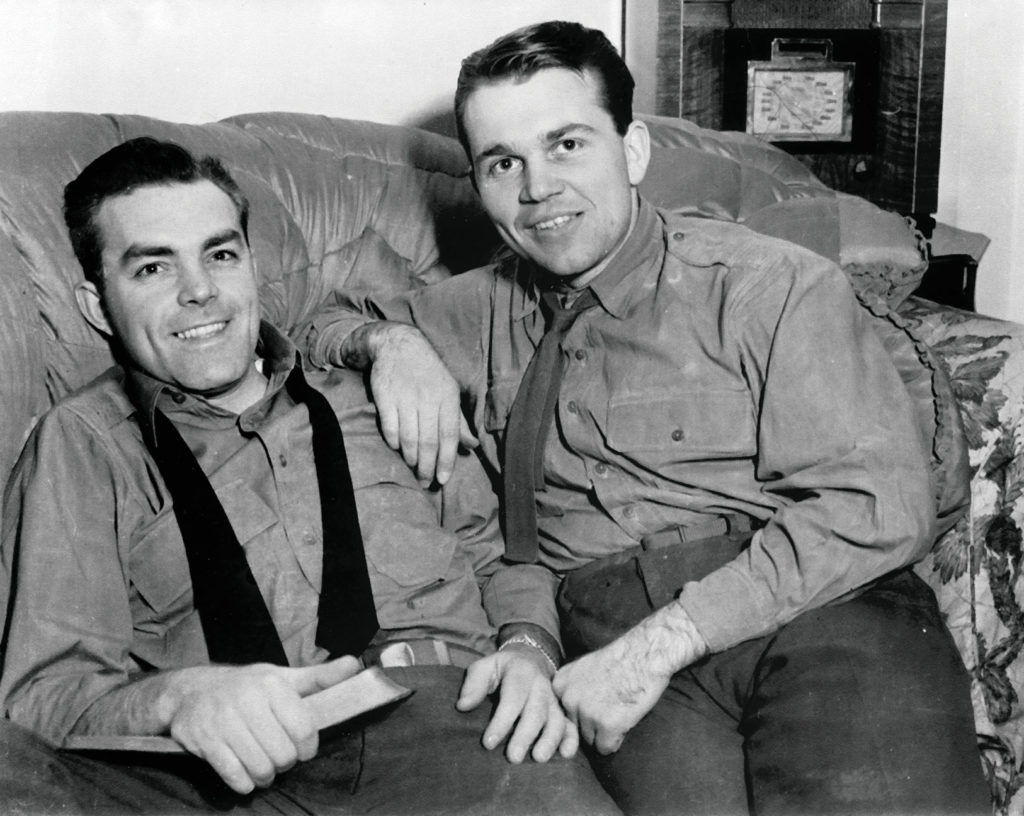

In the fall of 1942, Kiley was plucked out of his infantry company in Northern Ireland, where he was training as a radio operator and three weeks away from deployment to North Africa. Stars and Stripes, the army’s newspaper, was going from weekly to daily, and needed experienced reporters. At 28, Kiley had a few years on many other staffers and draftee reporters, and he became a mentor and friend to younger newsmen, including Andy Rooney (later of 60 Minutes fame), Jimmy Cannon (who would become a celebrated sports writer), and Earl Mazo (a leading political reporter in the 1950s, and Richard Nixon’s official biographer). He flew on bombing raids, trained with Army Rangers, and cranked out a two-sided single-sheet edition of Stars and Stripes from Utah Beach for a few weeks until he and a small team were able to set up the paper’s continental edition in Cherbourg. Kiley was managing editor with the paper’s Liège edition when, in April 1945, he was assigned to be Eisenhower’s pool reporter.

written in history

After Eisenhower phoned Churchill, Kiley quickly learned that the premature surrender story—which, under the headline “Nazis Quit,” quoted a “high official” in San Francisco—had stemmed from a remark by Senator Thomas T. Connally (D-TX). As word spread that Connally was the source, the senator explained to another reporter that the Germans had surrendered “in fact, if not on paper.” A politician’s wish to show off, combined with a reporter’s ambition, had produced the false report.

Still, V-E Day was not an “if,” but a “when.” German divisions were surrendering daily. Allied units were liberating concentration camps. The United Nations Commission for the Investigation of War Crimes was already identifying war criminals. Although pockets of hardcore Nazis continued to fight, even German-run radio stations were reporting that the Wehrmacht was smashed and surrendering en masse.

The first step to final unconditional surrender came on May 4, when Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, Hitler’s successor as Führer, authorized Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg—Dönitz’s successor as commander of the German navy—to sign cease-fire terms with British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery outside Wendisch Evern, a village in northwest Germany. Dönitz told Friedeburg to surrender all forces in northern Germany, Holland, and Denmark, and all laid down their arms on May 5—the day Friedeburg set out for Reims to begin negotiations for a general surrender. On May 6, General Hermann Niehoff, commander of some 40,000 German forces near Berlin, surrendered to Red Army forces in Breslau, east of the German capital. Half an hour later, General Alfred Jodl, German high command chief of staff, flew to Reims to join Friedeburg to negotiate specifics for unconditional surrender.

As pool reporter, Kiley would be the only journalist in close proximity to the talks, and his notes would be shared with the world press at the surrender signing. “Close proximity” meant an office outside the main negotiating room. Kiley would receive steady updates from Eisenhower’s longtime aide, Lieutenant Colonel Ernest “Tex” Lee, and, when possible, SHAEF chief of staff General Walter Bedell Smith, who led the proceedings. Eisenhower was on the scene but not taking part in face-to-face interactions with the Germans.

Seventeen reporters and photographers were being flown in from Paris to witness the signing. En route, they were required to agree to an embargo prohibiting release of the story. They were told SHAEF would lift the embargo within hours.

The atmosphere around SHAEF was tense. No one involved had had much sleep. Kiley noted that when idle, especially on their first day at Reims, the Germans fell asleep almost instantly. Jodl and Friedeburg puffed away on a supply of cigars they had brought. To ease the pressure and pass the time between bursts of negotiating, SHAEF staff and Kiley smoked constantly. The haze inside the school rarely dissipated.

For 34 hours, from the arrival of the first Germans to the signing of the papers, Kiley kept concise notes of arrivals, departures, facial expressions, food consumption, demeanors, and points of negotiation and disagreement leading to the final deal and the signing, at 2:41 a.m. on Monday, May 7. Jodl then stood to address Smith. Kiley’s story for the May 8 Stars and Stripes describes what came next:

“General,” Jodl began. “With this signature the German people and the German armed forces are for better or worse delivered into the victors’ hands.

“In this war, which has lasted more than five years, both have achieved and suffered more than perhaps any other people in the world. In this hour I can only express the hope that the victor will treat them with generosity.”

Jodl broke halfway through his address, and appeared on the verge of tears. He regained his composure however, and finished with a strong voice. His hands were trembling when he finished.

inside scoop

The war was over. But there was a new problem. Although the Soviets had a representative at Reims, General Ivan Susloparov, he had signed without Joseph Stalin’s endorsement. The Soviet premier demanded a surrender of his own, in Berlin. Stalin’s insistence meant that Eisenhower, Churchill, and Truman could not officially acknowledge the surrender until May 8, in order for everyone to assemble in Berlin and to account for time differences. A second surrender ceremony created a logistical nightmare for Americans and Brits—especially for reporters. The newly extended embargo demanded they sit on the story of the century for another 36 hours.

Kiley had warned Eisenhower’s staff that the news would be “damn difficult to hold.” And word was leaking out all over. German radio acknowledged the capitulation at 1:03 p.m. London time—8:03 a.m. EST. With no official statement from Churchill, the BBC announced that the war was over, citing the German broadcasts. Awaiting official word, throngs jammed Times Square in New York City, Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, Piccadilly in London, and the Champs- Élysées in Paris.

Through the early morning hours, furious reporters who had signed the SHAEF embargo clamored for permission to break it. “The absurdity of attempting to bottle up news of such magnitude was too apparent,” AP reporter Edward Kennedy wrote later. Kennedy, who returned to Paris later that morning, rationalized that Allied censors must have cleared the German radio stations to confirm the surrender, which, for him, invalidated the embargo. He found an unmonitored phone line, called the AP bureau in London and, without telling his editors that he was breaking an embargo, dictated a “flash” report at 9:24 p.m., Paris time. The story moved on the AP wire at 9:35 a.m. EST. The scoop was Kennedy’s.

“Well, you know all about it now,” Kiley wrote to Billee. “I felt the unconditional surrender would leak out ahead of time; and it has.” Kiley was disappointed. There wasn’t time to dwell on it, though: he was headed to Berlin in a C-47 for the second show, again serving as pool reporter, and likely the only reporter to witness both signings.

“The negotiations in Berlin went on all afternoon and night before the ceremony started after midnight, Berlin time,” he wrote to his wife, describing an exhausting jumble, with an official victory banquet and “24 toasts, no sleep for gosh knows how long, vodka, champagne, cognac, wine, caviar, squab, Russian cigarettes, but also the picture of hopeless people, weary refugees streaming through Berlin, smoldering fires everywhere.”

After filing his story, Kiley had time to explore Berlin, including the remains of Hitler’s Chancellery, where he snagged a few Reich relics, before boarding a flight to join Eisenhower in Paris.

“I think sometimes it is all a wild dream,” he wrote Billee later that day. “This morning I was driving and walking through what is left of a completely destroyed Berlin. This afternoon I sat at a table outside a sidewalk cafe on the Champs-Élysées, watching one of the most unbelievable and colorful sights, thousands of Parisians and soldiers of all nations just walking in a solid mass along the wide boulevard.”

Kiley’s surrender stories played on page one in all Stars and Stripes editions, and were picked up stateside in numerous papers, including the New York Herald Tribune, which hired Kiley after the war as a reporter, then an editor.

The war was over for Ed Kennedy, too, but he wasn’t done with combat. Two days after the New York Times ran his surrender flash, the paper published an editorial saying Kennedy had committed a “grave disservice” to the newspaper profession. Fifty-four reporters—Kiley included—signed a condemnation of Kennedy. SHAEF stripped him of his press credentials and the AP sent him stateside, firing him the following November. “I would do it again,” Kennedy said afterward. “The war was over; there was no military security involved, and the people had a right to know.” He died in 1963, never working again for a big media outlet and, according to his daughter, a somewhat broken soul.

final story

My dad died in 2001 at age 87, having worked as a daily newspaper editor for the New York Herald Tribune until it folded in 1966, and then editor–in-chief of the New York Law Journal until he was 76. I had been working as a reporter for a while myself, at CNN, when I learned about the broken embargo and Kennedy’s censure. I asked my father how he felt; he said the whole situation “was awful” for the reporters. But he was unwavering in his belief that Kennedy was wrong to break the embargo, and certainly wrong to do so without involving his editors in the decision. Never given to needless embellishment, Dad found it easier to talk about his role, which he described to Billee from Paris while sitting at that café.

“I am satisfied that I did a good job,” he told her.