EXECUTIVE MANSION,

Washington, D.C., September 17, 1864—10 a.m.

Major-General SHERMAN:

I feel great interest in the subjects of your dispatch mentioning corn and sorghum

and contemplated a visit to you.

A. LINCOLN.

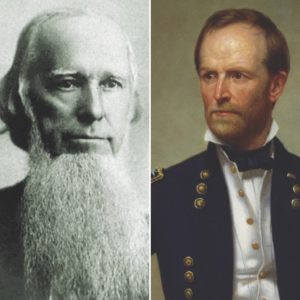

This short, cryptic message says more than it seems. Two days before, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman had telegraphed Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, the army’s chief of staff in Washington, D.C. Sherman had taken Atlanta and was residing in the city, making plans for his next campaign. “All well,” as he commonly put it; “troops in fine, healthy camps, and supplies coming forward finely.”

Then he added: “Governor Brown has disbanded his militia, to gather the corn and sorghum of the State. I have reason to believe that he and Stephens want to visit me, and I have sent them a hearty invitation.”

A couple of things are going on here. That Georgia Governor Joseph E. Brown, an ardent champion of local defense, would—with a Yankee army of roughly 60,000 men encamped and unchallenged in northern Georgia—send his state militia home to gather crops was eye-catching.

Even more important, why would the governor of Georgia and the vice president of the Confederacy (both widely known critics of the administration in Richmond) want to meet with Sherman?

Lincoln, the master politician, could figure it out without knowing the background, and the prospect led him to contemplate (as he would write) making a trip to visit Sherman in Atlanta. He might have actually looked forward to seeing Stephens. The two, after all, had served together in the U.S. House of Representatives in the 1840s.

In fact, young Abe may have looked up to the representative from Georgia. During the Mexican War, Alexander Stephens, who disliked James K. Polk, opposed the president’s plan to acquire territory from Mexico. On February 2, 1848, Stephens, a three-term congressman, delivered a speech in the House that denounced Polk’s war as “a wanton outrage upon the Constitution” and decried Polk’s policies as “disgraceful, ruinous and infamous.” Sitting on the floor that day was Lincoln, a first-term congressman from Illinois. Lincoln was so moved, that he wrote that very night to William Herndon, his close friend and law partner, “I just take up my pen to say, that Mr. Stephens of Georgia, a little, slim, pale-faced, consumptive man…has just concluded the very best speech, of an hour’s length, I ever heard. My old, withered, dry eyes, are full of tears yet.”

Lincoln’s respect for that “little, slim, pale-faced, consumptive man” would continue. During the Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858, when the “Rail-Splitter” was fighting for a Senate seat, he referred to Stephens as “that giant in intellect” and “that great intellect of the South.”

Even as the nation lurched toward civil war, Lincoln kept his eye on Stephens. And vice versa: Just days after Lincoln’s election to the presidency, Stephens addressed the Georgia legislature, cautioning that the Northern election results were not reason enough for Southern secession. Likening the Union to a worthy sea vessel, he counseled, “Don’t abandon her yet; let us see what can be done to prevent a wreck.”

“The ship has holes in her,” someone yelled in the chamber.

Stephens agreed. “But let us stop them, if we can; many a stout old ship has been saved with richest cargo after many leaks; and it may be so now.”

Stephens’ speech was printed widely. Lincoln read it in a Springfield, Ill., paper, and wrote him, asking for a copy.

Then, a month later, the president-elect was even considering asking Stephens to join his Cabinet, as Secretary of the Navy—though evidence of the Georgian’s ever having been to sea is hard to find. (Talk about relationship!)

Yet for Lincoln, there was an irreconcilable debate with Stephens that ultimately wrecked their friendship. “You think slavery is right and ought to be extended,” Lincoln wrote Stephens a few days before Christmas 1860, “while we think it is wrong and ought to be restricted. That I suppose is the rub. It certainly is the only substantial difference between us.”

Long before the war, Stephens had acquired the reputation as “the Mephistopheles of Southern politics,” who wanted things his way. In the Montgomery, Ala., convention that organized the Confederate government, he let it be known that he would accept the presidency only if he could handpick a Cabinet whose members’ constitutional views accorded with his own. Stephens was passed over for the job but did land the No. 2 post.

Although, as one observer noted, Stephens’ vice presidency was “a sop to get rid of a trouble maker,” it didn’t quite work. Publicly, Stephens withheld support of Davis’ proposals and began spending a lot of time away from Richmond, holing up at his mansion in Crawfordville, Ga. He allied himself with other anti-Davis politicians, such as Georgia’s Governor Brown. When Brown voiced opposition to Confederate conscription in 1862, Stephens was on the sidelines cheering. Later he argued that Davis had no power to declare martial law. When the president considered suspending the writ of habeas corpus, Stephens wrote his brother, Linton: “Better that Richmond should fall and that the enemy’s armies should sweep our whole country from the Potomac to the Gulf than that our people should submissively yield to one of these edicts.”

Then, in mid-March 1864, Stephens delivered a passionate three-hour tirade against presidential abuse of power on the floor of the Georgia legislature. “Tell me not to put confidence in the President,” he warned. Many Southern newspapers reprimanded the vice president; Northern editors picked these up and gleefully reprinted their columns as signs of a weakening rebellion.

Joe Brown was not idle either. In an address to the state legislature read on March 16, 1864, he roundly condemned the administration in Richmond: “Probably the history of the past furnishes few more striking instances of unsound policy combined with bad faith.” But he added a kicker: The war should be ended through negotiations with the North. Henceforth, he argued, after every big Confederate victory, the South should offer peace terms to Lincoln. (Little could Brown envision that there would be no more big Confederate victories.)

Because of their pronouncements, many Georgians viewed the governor and vice president as two peas in a pod—and unsavory ones at that. The Savannah Republican went so far as to assert that if Georgians were “ready to support Brown and Stephens…they have made up their minds to an act of suicide.”

Sherman was probably unaware of all this Rebel in-fighting, but he certainly took advantage of it. Shortly after the fall of Atlanta, Joshua Hill, a well-known Georgia Unionist, visited Sherman at his headquarters, John Neal’s stately house in the city’s downtown. Hill wanted to retrieve his son’s remains from a northern Georgia battlefield and asked permission to get there (it was under Federal control). Sherman not only agreed, but also asked Hill to stay for dinner.

In his Memoirs, the general recalled their table-talk. “We naturally ran into a general conversation about politics and the devastation and ruin caused by war,” he remembered. Hill foresaw even more of this ruin for Georgians, to the point of hoping Governor Brown would “withdraw his people from the rebellion.”

Sherman jumped on this, declaring that if Brown seceded from Secessiondom, “I would spare the state” during his next campaign (he was already thinking of a march to the sea). Sherman went so far as to ask Hill to meet with Governor Brown and invite him to Atlanta for a peace meeting with Sherman. Through an emissary, Sherman also sent a meeting invitation to Alexander Stephens, then secluded at his home in middle Georgia.

To be sure, Cump was acting on his own, without authorization from his government to involve himself in political matters. (It would not be the last time he overreached, though; recall the trouble he got himself into in April 1865 when he discussed with General Joseph E. Johnston the surrender of all Confederate forces.) It didn’t matter. Sherman saw his diplomatic maneuvering as “a magnificent stroke of policy.”

As it turned out, Brown never met with Sherman, feeling he had no power to enforce any agreement even if they reached one. “As our interview could therefore result in nothing practical I must decline the interview,” Brown wrote. In a public letter he argued that Georgia had the right to make a separate peace, but would not leave her sister states in the lurch. Many Confederate newspapers as far away as Richmond printed the governor’s letter, in which Brown had written:

If President Lincoln and President Davis will agree to stop the war and transfer the settlement of the issues from the battle-field to the ballot-box, leaving each Sovereign State to determine for herself what shall be her future connection, and who her future allies, the present devastation, bloodshed and carnage will cease, and peace and prosperity will be restored to the whole country. On the other hand, if this is not done, the war will last for years to come….

The Atlanta Daily Intelligencer, a strong supporter of the governor, commented approvingly on his “admirable reply,” declaring, “the public…have been anxious to know what reply was made by his Excellency. Their curiosity can now be gratified,” the editor commented in a virtual sigh of relief.

As for Sherman’s invitation, the vice president declined on the same grounds as the governor, stating that he would meet Sherman only “with the consent of our authorities.” Privately, Stephens was being warned of Yankee chicanery. Robert Toombs, like “Aleck” no fan of Jeff Davis, cautioned: “If Sherman means to do anything, he means to detach Georgia from the Confederacy.”

When word of Sherman’s peace plot got out, the Georgia press went wild. The Columbus Daily Times on October 6 declared, “the mere whisper of…peace is criminal—he who would entertain it with no abatement by the foe, is a traitor”—strong words indeed when you’re talking about a governor and the vice president.

Brown had replied to Sherman by September 30; Stephens’ letter was dated October 1. President Lincoln learned of these disappointments only later. Indeed, on September 27, Lincoln remained hopeful. Upon hearing that Jeff Davis was traveling to Georgia, Lincoln wired Sherman, “I judge that Brown and Stephens are the object of his visit.”

John B. Jones, a senior clerk in the Confederate War Department, wrote on September 20: “There is a rumor that Sherman has invited Vice-President Stephens, Senator H.V. Johnson, and Gov. Brown to a meeting with him, to confer on terms of peace—i.e., the return of Georgia to the Union.”

Two days later, Jones wrote in his diary: “It is said the President has gone to prevent Governor Brown, Stephens, H.V. Johnson, Toombs, etc., from making peace for Georgia with Sherman.” [Robert Toombs and Herschel Johnson were the uninvited Georgia senators.] So the rumor of a Sherman-Stephens-Brown meeting had reached the level of Richmond gossip. Mary Boykin Chesnut, the famed diarist, wrote in her journal that she had heard “Joe Brown, the governor of Georgia…wanted a peace conference. They mean to ignore Jeff Davis and Lincoln and settle our little differences themselves.” (Only Mary Boykin Chesnut could wryly refer to America’s bloody civil war as “our little differences.”)

During his visit to Georgia on September 22-27, Davis did not meet with Stephens or Brown. But the notion of the Confederate president having to quash two wayward underlings was a lip-smacking one to Old Abe. Nevertheless, those pesky Georgia politicians wouldn’t go away. Linton Stephens, the VP’s brother, was a member of the General Assembly. On November 9, he introduced a resolution urging the Davis administration to call a convention of the states to discuss a path toward peace. The Confederate president’s response can be imagined; Davis called the idea “another form of submission to Northern dominion.”

Two and a half months later, Lincoln (and Seward) ended up meeting with Stephens (as well as Confederate Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell and Confederate Senator Robert M.T. Hunter of Virginia) at Hampton Roads, Va. to talk peace—though no agreement was reached. It was cold that day in early February. As “Little Aleck,” known for his scrawny torso, peeled himself out from a layer of coats, Lincoln quipped that he had never seen such a small nubbin come out of a big shuck.

Shucks, indeed. The meeting never happened and Lincoln never traveled to Atlanta. But the idea that a Georgia-based armistice might somehow have brought an earlier end to the war is a counterfactual thought worth pondering.

Stephen Davis, who writes from Cumming, Ga., is a frequent contributor and member of the America’s Civil War Editorial Advisory Board. Tom Elmore, who writes from Columbia, S.C., has a B.A. in history and political science from the University of South Carolina. He is the author of four books and numerous magazines articles dealing with South Carolina during the Civil War. His article “The Myers Letter,” examining the story of a document often propagated as a hoax, appeared in America’s Civil War’s January 2005 issue.