The present-day notion of medieval warfare is of longbowmen standing shoulder to shoulder loosing arrows and knights charging across open fields before engaging in brutal hand-to-hand battle. Hastings, Bannockburn, and Agincourt come to mind. Such battles, however, were the exception, for during the Middle Ages warfare was a much more complicated affair that more often than not involved siegecraft.

After his 1066 victory at Hastings, William the Conqueror initiated a massive castle-building program in England that was instrumental in completing the Normans’ subjugation of the Anglo-Saxons. Throughout medieval Europe and the Middle East, the castle functioned as a private fortress that, among its other roles, physically—and symbolically—proclaimed the status and strength of its lord to all comers, friend or foe. Even the simplest earth and timber motte and bailey castle, used to great effect by the Norman kings of England, validated the power of the conquering force.

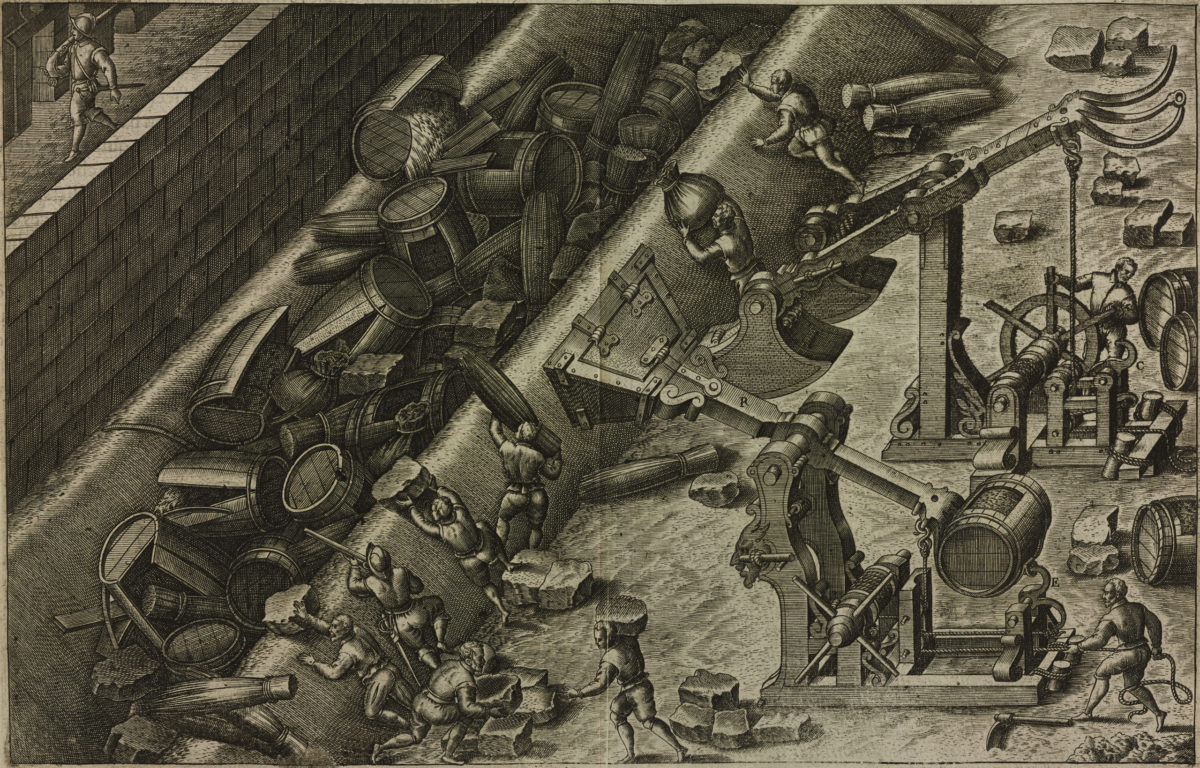

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, castles evolved into powerful fortresses capable of defying intensive assaults. At the same time, in order to combat strengthened castle defenses, siegecraft developed. By the late Middle Ages, few major campaigns took place without at least one castle siege. Indeed, while battles such as Crécy (1346) have gleaned all the glory, it was not until the siege of Calais in the following year that the English made significant progress in their fight against France. The successful castle siege skillfully combined sophisticated science with specific standards of conduct known to, but not always practiced by, the participants. Ultimately, the siege dominated medieval warfare for at least as long as the castle dominated the social and political order of the day.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Recommended for you

Complicated Affair

Besieging a castle was a much more complicated affair than simply ‘rushing into the breach,’ as Shakespeare’s Henry V exhorted his troops before the 1415 siege of Harfleur. Sieges, likewise, involved much more than bombarding a fortress until either the garrison surrendered or the defenses were overcome. In fact the medieval siege was a complex, highly choreographed process that ended with a castle assault only when other tactics had failed to force a surrender. Besieging a castle involved assembling and paying an army, gathering supplies, and hauling them to the siege site. Because the costs were so high, military leaders normally did not rush into a siege. Indeed, if a besieging army lost too many men in an initial onslaught, it was often forced to retreat or give up the siege entirely. If it was successful enough to gain control of the castle, the army’s now-weakened troops might not be capable of repulsing a renewed attack by forces sent to relieve the garrison. Consequently, the full-out siege was normally a last resort, unless, of course, the attacking king or lord had a particular investment in breaking his opponent.

Early medieval sieges were generally directed against towns or major cities, which were often fortified, rather than at individual castles. As castle sieges became more commonplace, besiegers devised methods to overcome increasingly complex defenses. Until about 1100, tactics mainly consisted of using firepower to break through the castle’s physical defenses or of starving out the defenders by blockade. During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, siege warfare became increasingly sophisticated, and by the mid-fourteenth century enormous timber war machines had become the mainstay of virtually every investment. At the same time, specific conventions for conducting a siege were well established. The most practiced soldiers followed traditional protocol, which encouraged honorable negotiation and surrender before an attacker pummeled the garrison into submission.

If You Fail to Plan, YOu PLan to Fail

Commanders first had to devise an overall strategy for taking the castle. They had to consider from where in the realm the best archers, skilled carpenters, blacksmiths, sappers, and engineers could be drawn. If a king was contemplating launching a siege, he would consider which lords owed him knights’ service and how many men-at-arms they would provide (knights normally were obligated to serve for forty days during the course of a year). Other considerations included how much timber, lead, tools, nails, food, drink, livestock, and other provisions were required for the duration of the siege and where they could be acquired.

The preparations undertaken prior to the 1224 siege of Bedford Castle by Hubert de Burgh for King Henry III provide a case in point. First, the archbishop of Canterbury, the king’s advocate, excommunicated the castle’s garrison, hoping to demoralize the defenders into surrendering. In the meantime, the besiegers began to assemble vital materials, laborers (including miners, carpenters, and masons), knights, and other fighters. Among the items required for the siege were iron, hides, charcoal, leather, and some nineteen thousand crossbow quarrels. The king ordered protective screens, bolts, hammers, mallets, wedges, tents, wax, and a variety of spices. He also made sure that several siege engines were readied and that gynours, or gunners, were on hand to operate the machines.

White Flag

The most satisfying way to successfully conclude a battle was without fighting. Indeed, many more sieges were settled by negotiation, bribery, or forms of intimidation than open warfare. Given the huge effort involved in coordinating a siege and assembling an army, potential besiegers made at least cursory efforts to convince the garrison, the constable, or the lord of the castle to surrender peaceably.

Surrender under honorable terms was a common way out of a siege. In many cases, the besiegers allowed the defenders a period of time, ranging from a week to forty days, to decide whether or not to give in. Truces effectively delayed a full-blown assault, so that the constable could contact his lord for directions on how to handle the situation or to gain assistance at the castle. Lengthy truces could also lead to the deterioration of the attacking army, particularly when knights’ forty-day service obligations neared completion and no reinforcements showed up to replace them. If members of a beleaguered garrison knew they had enough food and drink to carry them at least forty days or had notice that relief was on its way, they knew they might survive the investment. Truces also gave the defenders time to construct their own siege engines, shore up their defenses, and build wooden hoards, or fighting platforms, on the battlements.

Let Us Commence

If the garrison refused surrender demands, the siege began with an overt act by the attackers, a symbolic sign of intent. At the siege of Rhodes in 1480, for example, Muslim forces hoisted a black flag to warn their opponents that they would attack. At times, attackers threw javelins or shot crossbow bolts at the castle gateway to signal their intentions. On occasion, siege engines hurled missiles. By the late Middle Ages, cannon fire signaled the beginning of sieges.

When a garrison refused to surrender, the balance of besieging forces would trek to the siege site, set up their encampment, and construct some basic defenses of their own not too far from the castle’s walls. Engineers would also begin erecting bulky, intimidating siege engines. Other soldiers fomented dissent in the surrounding countryside in an effort to recruit supporters and seize control of crops and other resources–assuming landowners and peasants had not already torched them. It was common for inhabitants of an area to use a’scorched earth’ policy to sabotage an impending siege. After gathering food, livestock, and other items for their own use, they intentionally burned their own lands to prevent the enemy from gaining any benefit from them. Often the resulting famine left the besiegers no alternative but to retreat.

Cracking the Egg

In order to ease access to the castle, attackers might first fill the strongpoint’s surrounding dry ditch or wet moat with tree branches, gorse, heather, loose earth, or whatever else was available. Alternatively, they might sail a barge to the base of the castle’s outer, or curtain, wall. Once the ditch could be crossed or the moat forded, the initial offensive could proceed rapidly. Often relatively light, the early assault primarily featured an escalade–an attempt to scale the curtain wall by ladders. The key to an escalade was for the attackers to climb the ladders as quickly as possible, leap onto the battlements, and begin fighting the defenders. During this effort, archers, crossbowmen, and slingers outside the castle provided protective fire for their comrades while shielding themselves behind screens known as pavises. The onrush would take place at several spots along the curtain wall in hopes of splitting up the garrison, diverting attention, and gaining access at whatever point might weaken.

At the same time, the besiegers assaulted the main gate’s heavy timber doors and attempted to set afire any timber rooftops shielding castle towers. They might also begin hammering the masonry defenses with picks, iron bars, and other tools while protected inside a hide-covered timber-and-iron framework, known variously as a cat, rat, tortoise, or turtle, which had been wheeled to the castle wall. Of course, the defenders made every effort to thwart the escalade by shoving ladders away from the walls, shooting at the besiegers, and dropping stones, quicklime, or hot liquids upon them.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

The Ups and Downs of Scaling a Castle Wall

It took nimble, sure-footed, quick-thinking men to maneuver their weighty armor and weapons and scale the walls successfully. At the siege of Caen in 1346, Sir Edmund Springhouse slipped off a ladder and fell into the ditch. French soldiers overhead swiftly tossed flaming straw on top of the Englishman and burned him alive. During the siege of Smyrna, Turkey, also in the fourteenth century, one of the besiegers climbed halfway up a ladder. When he rested and took off his helmet to see how much farther he had to climb to reach the top, a crossbow bolt shot from the battlements hit him between the eyes, killing him.

If an escalade proved successful, the besiegers would chivalrously offer the garrison a final chance to surrender with honor or to call a temporary truce. On the other hand, when an escalade failed to make a serious dent in the defenses, the attackers intensified the onslaught. They also began constructing siegeworks or a siege castle, sometimes called a countercastle, in preparation for a prolonged conflict. Then they would man the era’s most destructive weapons–siege engines.

Sieges are Like Snowflakes

No two sieges were ever conducted in exactly the same way. How the operation developed depended on the strength, size, and resources of the attacking army; the condition and complexity of the castle’s fortifications; the fortress’ armory and supplies; as well as the resolve of the besieged. An army might employ several different types of siege engines to bring down the battlements while also attempting to force surrender by other means.

Medieval siege engines originated in Greek, Roman, and ancient Chinese warfare. Archimedes was responsible for advancing siege technology, which the Greeks had introduced before the fourth century b.c. The renowned mathematician and engineer developed several engines as early as 213 b.c., when the Greeks fought the Romans at the siege of Syracuse. His prototypical petrariae, great stone-throwing engines, were copied and modified by the Romans and later used throughout the medieval world.

Onager and Mangonel

The Romans bequeathed two important siege engines to medieval warfare. The onager, meaning wild ass, consisted of a heavy timber trestle mounted midway on a horizontal timber frame, and it hurled a missile in an overhead arc, rather like a child flinging peas with a spoon. When fired, the engine’s rear kicked upward–hence the descriptive name. The onager’s medieval counterpart, a mangonel, employed a long timber arm or beam held in place by skeins of tightly twisted rope stretched between two sides of the frame. Gunners would ratchet back the arm and place a large stone or incendiary device in the scoop at its end. When the firing arm was released, the projectile would arc out to a range of up to five hundred yards.

Despite the inherent inaccuracy of this torsion-powered machine, which is sometimes called a catapult, the mangonel could effectively break through stone walls or knock down a castle’s battlements. Mangonels were occasionally used to hurl dead carcasses over battlements in an effort to spread disease among the castle defenders. In response, defenders sometimes used their own siege engines to toss back one of the besiegers–if they had managed to capture one during the escalade or during a raid outside the castle–or a messenger who carried unacceptable surrender terms.

Used in battle across Europe and the Holy Land, mangonels saw action when the Vikings besieged Paris in 885, at the 1191 siege of Acre, and at the 1203-4 siege of Chteau Gaillard. Mangonels were also on hand in 1216, when France’s Prince Louis besieged mighty Dover Castle, on England’s southeastern coast. Despite Louis’ greatest efforts, which included a battery of siege engines, he failed to breach Dover’s formidable defenses.

Ballista and Springald

The Romans modified the modest Greek siege engine known as the scorpion into a horrific dart-firing machine called the ballista, which was later used during the Middle Ages. Like the mangonel, the ballista was powered by twisted skeins of rope, hair, or sinew. But, instead of firing its missiles in an overhead arc, the ballista loosed heavy stones, bolts, and spears along a flat trajectory. Easy to fire accurately, smaller ballistas were effective anti-personnel weapons that could skewer warriors to trees, while large versions could send a sixty-pound stone at least four hundred yards.

A variant of the ballista was a tension-driven device called the springald, which closely resembled a crossbow in function. Used to fire javelins or large bolts, it had a vertical springboard fixed at its lower end to a timber framework. Soldiers manually retracted the board, which moved like a lever. When released, the springboard smacked the end of the projectile, propelling it toward its target. Springalds also made excellent defensive weapons. At Chepstow Castle in Wales, Roger Bigod mounted four springalds on the corners of the great keep to hold the enemy at bay. Although the springalds no longer survive, the platforms on which they stood during the late thirteenth century are still visible.

Battering Rams and Bores

While their comrades busily managed the siege machines, other besiegers used battering rams or bores (chisellike poles) to pound the main gateway and crash through the walls. Rather than simply grabbing a giant log and repeatedly thrusting it at castle gates or stone walls until they broke through, medieval soldiers did their ramming from inside a timber framework called a penthouse or pentise. Used in warfare as early as the sixth century, rams and bores were often pointed and iron-tipped for added effect, and were sometimes shaped, not surprisingly, as rams’ heads. The ram or bore was suspended by chains or ropes from the penthouse ceiling so that the operators, sometimes scores of men, could swing the beam rhythmically and pound the walls into submission.

The movable penthouse consisted of a lanky timber gallery covered with a pointed roof, cloaked with wet hides to prevent burning, and braced with iron plates to deflect missiles dropped by the defenders overhead. The attackers used rollers, levers, ropes, pulleys, and winches to maneuver the penthouse into place at the base of the castle wall. They then removed the wheels to stabilize the structure.

Rams were most effective against timber defenses, particularly the heavy oak doors barricading most main gates. Against stone fortifications, they worked best when battering corners. Defenders would counter by using hook-ended ropes to grab the ram and overturn the penthouse or by swinging beams on pulleys to smash the timber cat as it approached the castle. Popular during the Crusades, battering rams were effectively employed in 1191 at Acre, a walled city with a formidable citadel. They became obsolete once the most powerful siege engine of all–the trebuchet–began to dominate European sieges.

And, Yes, the Trebuchet, the king of Sieges

The terrible trebuchet was the mother of all stone-throwing siege engines. A purely medieval invention, the giant counterweight-powered machine struck fear into the hearts of many garrisons. Considerable question exists about the trebuchet’s origins. Peter Vemming Hansen, director of the Medieval Centre in Denmark, argues that the first trebuchets arrived in the Nordic countries by way of northern Germany and may have been used by the Vikings as early as a.d. 873. He states that the first trebuchet arrived in Denmark as early as 1134 and emphasizes that the counterweight engine was definitely a Western invention that spread eastward.

Trebuchet may derive from the Old French word, trabucher, which means to overturn or fall, and probably described the action of the timber beam that falls over its pivot. The word made its first appearance in the account of the siege of Castelnuovo Bocca d’Adda written by Johannes Codagnellus in the late twelfth century. According to the Chanson de la Croisadde Albigeoise, Simon de Montfort used a ‘trabuquet’ against Castelnaudary in 1211, destroying a tower and the hall. Powered by a counterweight mechanism and able to accurately hit targets at a range of five hundred yards with missiles exceeding three hundred pounds in weight, the trebuchet’s ability to relentlessly pound a curtain wall until it broke open made the engine invaluable during a siege.

Engineers in seventh-century China may have perfected an early form of the trebuchet, the perrier–a traction trebuchet operated solely by men pulling down on ropes attached to a pivoting arm. Its medieval counterpart, however, effectively applied the principle of counterpoise and replaced manpower with a counterweight. Lead weights or a massive pivoting ballast box filled with stones, sand, or dirt–sometimes weighing as much as twenty tons–was fixed to one end of the engine’s arm, which could be up to sixty feet long. The other, longer end of the arm would be hauled down and a heavy stone placed in a leather pouch that was attached by two ropes to the beam’s end. When the arm was released, the force created by the falling weight propelled the long end upward and caused the missile to be flung slinglike toward a target. The same spot could be pummeled repeatedly, and range and aim could be adjusted. Eventually, the incessant pounding breached walls, killed personnel, or crushed siege engines defending the castle.

Counterweight trebuchets probably arrived in England when Prince Louis of France besieged Dover Castle during his near-successful invasion of England. In 1216 the French army first used a variety of techniques and weapons to try to breach the resistant castle walls. Then the two sides signed a truce in October, and Louis moved most of his troops to London. After the English garrison broke the truce, killed many of the French soldiers posted outside the castle, and interfered with the movement of troops and supplies, the prince returned to Dover, which he again besieged. The following May, he used a trebuchet, but it proved ineffective. After the defeat of the French fleet in August 1217, the prince gave up his ambitions for the English throne. Despite the losses and his retreat back to France, Louis left an important legacy in England: new technology that not only changed how sieges were conducted but also influenced the design of castle defenses.The trebuchet was also useful for flinging all sorts of projectiles over the curtain walls to create mayhem. In 1346 outside Kaffa, on the Crimean Peninsula, an unknown but virulent disease savaged a besieging Mongol-Tartar army. Hoping to likewise weaken their enemies, the Asian warriors used a trebuchet to toss the diseased bodies of their dead comrades at the Genoese army, which held the major port and cathedral city. The Italian soldiers then unwittingly carried the mysterious disease–later known as the Black Death–back to their homeland, and it subsequently devastated Europe.

Trebuchets also hurled incendiary devices, including flaming missiles, casks of burning tar, and pots of Greek fire, a particularly nasty concoction whose ingredients included saltpeter and sulfur. The fiery substance stuck like glue to almost any surface and was nearly impossible to extinguish, except with sand, salt, or urine–water only fanned the flames. In twelfth-century medieval France, Count Geoffrey V of Anjou used a siege engine to hurl a heated iron jar filled with Greek fire at the castle of Montreuil-Bellay, which promptly fell after having endured a three-year siege.

Warwolf

England’s Edward I, a master of siegecraft as well as castle building, was particularly fond of the trebuchet and used it and other siege engines against castles in Scotland, Wales, and France in the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. In 1304 Edward I assaulted Scotland’s Stirling Castle using thirteen siege engines, including a springald, a battering ram, and an enormous trebuchet named Warwolf, which, when disassembled, filled thirty wagons. According to Michael Prestwich, who has written extensively on the reign of Edward I, historic documents indicate that the construction of the giant trebuchet took five master carpenters and forty-nine other laborers at least three months to complete. A contemporary account of the siege states, ‘During this business the king had carpenters construct a fearful engine called the Warwolf, and this when it threw, brought down the whole wall.’

Even before construction could be completed, the sight of the giant engine so intimidated the Scots that they tried to surrender. Edward, declaring, ‘You don’t deserve any grace, but must surrender to my will,’ decided to carry on with the siege and witness for himself the power of the masterful weapon. The Warwolf accurately hurled missiles weighing as much as three hundred pounds and leveled a large section of the curtain wall.

In 1300 Edward had besieged Caerlaverock Castle. Located in the Scottish Borders about three miles from Dumfries, the castle of the Lords Maxwell posed a formidable obstacle to the king’s plans to control Scotland. In a contemporary poem titled ‘The Song of Caerlaverock,’ Walter of Exeter, a Franciscan friar, chronicled the entire event, from the gathering of troops and materials for the siege train to the assault with siege engines. Originally composed in French, the work remains an invaluable record of the tactics and technology involved in conducting a castle siege.

According to Walter, ‘Caerlaverock was so strong a castle that it feared no siege before the King came there, for it would never have had to surrender, provided that it was well supplied, when the need arose, with men, engines and provisions.’ Edward required all of England’s noblemen who owed knights’ service or held property in his name to assemble at Carlisle, in the northwestern corner of the country. He commissioned Brother Robert of Ulm as his master mason, and a variety of specialist laborers to construct a cat, battering ram, belfry, springalds, and robinets (probably trebuchets). Edward also stockpiled large stones, timber, bolts, animal hides, and tools. Ships hauled in supplies by sea, while the siege train journeyed northward to the castle.

Once at their destination, the English army set up camp, erected tents and huts, stabled the horses, and foraged in the surrounding countryside for timber and other resources. Then they laid siege to the Scottish castle. English and Breton soldiers toting small arms charged the castle walls while siege engines began their assault. Despite suffering several deaths, the garrison remained defiant, and the siege continued for some twenty-four hours. Finally, the siege engines breached the curtain wall. Waving a white flag, the Scots first requested a truce to discuss terms, but their spokesman was killed by an arrow, and they soon surrendered. The English ended the siege by formally taking over the castle and flying the king’s standard. The garrison had amounted to only sixty men, whose fates varied from reprieve to hanging.

Sappers and Miners

If a castle was strong enough to withstand the pounding of siege engines and if the garrison refused to surrender, the commander of the besieging army still had several options. He could employ sappers to dig tunnels underneath castle walls and towers. Once the miners reached their destination, they filled the tunnel, sometimes called a sap, with tar-soaked beams, branches, and other flammable material that was set on fire. If things went according to plan and the flames consumed the timber props inside, the tunnel would collapse, as well as the tower or section of wall overhead. Besiegers would then storm through the breach.

Undermining was not without risks, and miners were sometimes killed when a tunnel collapsed too early. Yet the technique was an effective tactic and resulted in the capture of formidable fortresses. In late 1215, England’s King John besieged Rochester Castle, which was held by a group of rebellious barons led by William d’Albini. For almost seven weeks John used five siege engines to pound away at the powerful stronghold, but he failed to take the castle from the well-supplied and well-armed defenders. The king then turned to his miners.

this article first appeared in military history quarterly

Facebook: @MHQmag | Twitter: @MHQMagazine

First the sappers managed to breach the outer wall, and John’s troops rushed into the bailey. In response, the rebels retreated to the protection of the great keep, which was one of the strongest in the kingdom. John’s sappers were soon undermining the southeastern corner of the huge rectangular structure and filling the tunnel with the usual flammable items.

Meanwhile, to ensure the keep’s demise, King John ordered his justiciary, Hubert de Burgh, to send ‘with all speed by day and night forty of the fattest pigs of the sort least good for eating.’ After the king had the swine killed, his sappers packed the tunnel with their carcasses. The subsequent fire burned so hot that the keep’s foundations cracked, and the corner and a portion of wall fell outward. The rebels still refused to yield and retreated to the opposite side of the keep, which was divided by a sturdy cross wall into two separate, self-sufficient areas. John then waited out the barons, who finally surrendered due to fatigue and hunger. When repaired, the new angle of the keep sported a more modern round turret.

Siege Tower or Belfry

During the late stages of a prolonged siege, attackers would often make use of one last great engine–the siege tower, or belfry. It was a multipurpose machine that would be rolled to the battlements of a castle so that the men secreted inside could climb onto the walls or operate weapons, such as battering rams and mangonels, from close-range positions of relative safety. Bringing a siege tower into the fray was an expensive prospect and required advance planning, plenty of building materials, skilled craftsmen, and enough soldiers to move the engine as close to the castle as possible. Sometimes disassembled belfries were transported to the siege and only assembled when absolutely necessary, for it could take several weeks to put the engine together. Only the wealthiest noblemen could afford to construct siege towers.

The wheeled wooden tower normally stood at least three stories high. Near the top, a strategically placed drawbridge lowered to allow the attackers to scramble onto the battlements. Some belfries rose well over ninety feet and were crowned with a mangonel or ballista. To protect the belfry from fire and the men inside from being shot, animal hides soaked in mud and vinegar covered the framework. On rare occasions, iron plates also offered protection. The mechanism itself might carry scores of soldiers, who climbed ladders to move between levels. A belfry at the 1266 siege of Kenilworth Castle held two hundred archers and eleven siege engines.

Moving the belfry into position was no mean feat. Attackers first had to ensure that the moat or ditch was filled in and the ground relatively smooth. Then strong, persistent men–and sometimes oxen–hauled the unstable, heavy tower into place at the foot of a curtain wall. Windy weather posed problems, and the large, slow-moving belfry was vulnerable to fire from castle siege engines, as well as archers and crossbowmen.

Each man assigned to a siege engine had a particular role to play. Some were responsible for moving the clumsy structure into place; others stood poised with containers of water to keep fires at bay. The ground level of a belfry often featured a ram, which swung on ropes or chains from the ceiling. Sappers might dig at the castle foundations from inside the tower. Archers, crossbowmen, gunners, and armored knights manned upper levels, firing at the castle defenders while waiting to pounce upon them when the drawbridge dropped onto the curtain wall.

During the 1224 siege of Bedford Castle, Henry III employed two enormous belfries to tower over the battlements and shelter archers firing at the garrison. The castle must have been a formidable foe to precipitate such an extensive and expensive undertaking. After it was captured, the king ordered the complete demolition of the fortress.

Good Old Hunger

Given the destructive power of siege engines, the devastation that mining could cause, and the determination of the attacking army, one would expect a breach in the castle’s walls or the surrender of the garrison during the later stages of a siege. But as often as not, the besiegers had to resort to a final tactic to force capitulation. With the attackers already in place around the castle, and much of the land scorched, the likelihood was poor at best that reinforcements and additional supplies would safely reach the besieged. Attackers could then attempt to starve out the garrison.

Of course, this wait-them-out approach could come early in a siege, if the attackers believed the garrison had few resources with which to defend themselves. Then a blockade might save lives on both sides of the fight, while also conserving the resources available to the besiegers if they decided to push ahead with a full-scale assault. Sometimes garrisons held out for months during blockades and forced the besiegers to retreat when their supplies ran out or disease became a problem.

Occasionally, a castle’s constable might concoct shrewd displays to induce an attacking commander to abandon his plans and move on. In 1096 at Pembroke Castle in Wales, Gerald de Windsor ordered that the garrison’s four remaining hogs be cut up and thrown over the curtain wall, creatively convincing his Welsh enemies that his stronghold was fully stocked. His actions suggested to the attackers that the castle was so filled with food that the men inside could resist a siege indefinitely. In fact, the garrison was on the verge of starvation, but Gerald’s plan intimidated the Welsh into a speedy retreat.

How to Surrender Your castle

When a garrison finally gave in, the men often symbolically signaled the besiegers of their intent to surrender. Many sieges ended with the waving of a white flag or the handing over of castle keys to the leader of the attacking force. Negotiations would then begin to ensure the safety of the garrison or of any important individuals remaining in the castle. For example, in 1326 John Felton, constable of Caerphilly Castle in Wales, withstood a four-month siege led by William, lord Zouche, in the name of Queen Isabella. While the castle ably withstood the battering, Felton began negotiating a pardon for himself and Hugh le Despenser II, boy heir to the lordship of Glamorgan. In March 1327, Felton obtained amnesty and surrendered the castle and its provisions.

As soon as a garrison surrendered, arrangements were made for the movement of captives and the payment of ransom, and the victors were expected to keep up their side of the bargain. A variety of solutions might be debated, including banishment, relinquishment of all personal property, or the symbolic humiliation of the captives, which included parading them barefoot. Not surprisingly, defeated leaders were often imprisoned or swiftly and brutally executed.

CannoNs Barge In

In the thirteenth century, cannons, or bombards, began to appear in medieval warfare. It was not until the late fourteenth century that cannons were developed to the point that they began to replace timber engines as the preferred siege machine. By 1415, when Henry V besieged Harfleur, the king’s favored weapon was the cannon, the fire from which devastated the castle’s barbican to the point that the English could then torch the castle and force the French garrison’s surrender.

In response to changing technology, castle-builders devised sturdier defenses to thwart the bombards, as at Craignethan Castle in Scotland, where low, thick bastion walls with cannon loops were added in 1530. As the construction of new castles waned, Henrician gun forts–Henry VIII’s so-called Italian ‘Device’ forts, armed with clustered circular batteries of heavy artillery that eased cannon positioning–began to take their place. Despite these developments, besieging armies continued to adhere to the conventions of warfare established centuries earlier.

Like the timber siege engines, in time the castle became obsolete, not just as a weapon in the medieval arsenal but also as a formidable residence. Yet castles continued to serve a military function until well into the seventeenth century, when they thwarted the efforts of Parliament to defeat King Charles I. As late as World War II, Dover Castle was still considered to have strategic value to the British army and was used by Churchill and his compatriots in the battle against Germany. While castles and trebuchets no longer play a critical role in the military theater, the conventions of siege warfare still guide the efforts of military strategists around the world.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.