After the devastating Union defeat at Chickamauga, Ga., on September 19-20, 1863, roughly 41,000 Army of the Cumberland troops retreated frantically into nearby Chattanooga, Tenn. They soon found themselves trapped by General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee, boasting approximately 52,000 effectives. By late October 1863, the Federal army faced two unpalatable choices: starve or surrender. Although Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas declared his intention to starve first, his superior, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, found neither option acceptable. The store of ammunition, food, and fuel, as well as forage for the horses and mules, was being depleted rapidly—at one point down to perhaps a five-day supply on hand—so time was not a luxury.

Grant adopted an ambitious plan originally proposed by Thomas’ predecessor, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans. The objective was to reduce by half the 60 miles of treacherous, rain-gutted roads from the Union supply center at Bridgeport, Ala., to Chattanooga by establishing a new route. Joseph Wheeler’s cavalry had already shown the old route’s vulnerability with his Sequatchie Valley Raid in early October, and access through Walden Ridge had also been effectively shut down.

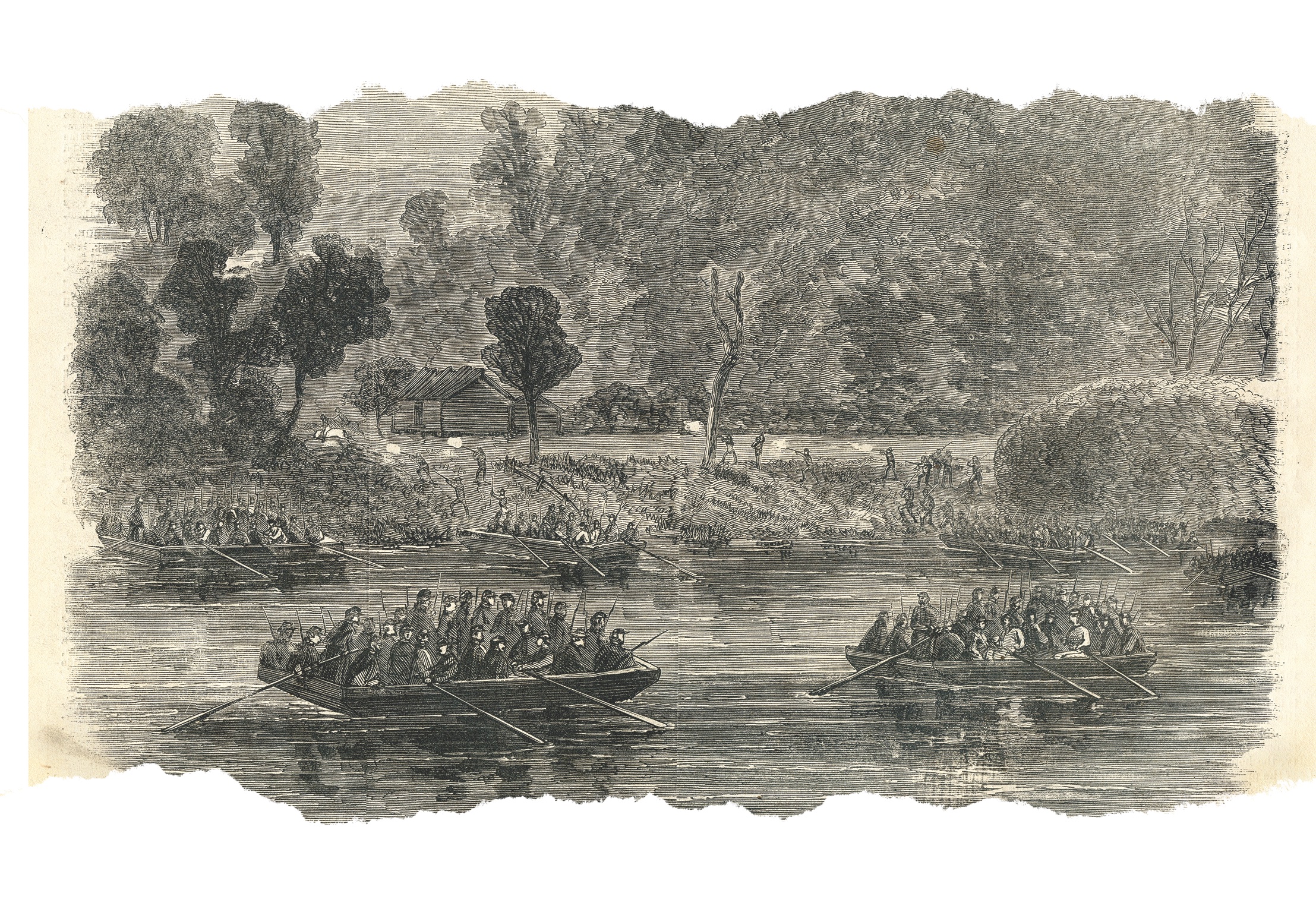

What would become known as the “Cracker Line” was to begin with the building of a bridge across the Tennessee River. Rosecrans proposed floating flatboats down the river out of sight of enemy guns on Lookout Mountain to establish a bridgehead on the south bank and allow a landing in force. Once the river was spanned, a 15,000-man force under Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker would arrive and proceed to Chattanooga with supplies.

Brown’s Ferry was determined the optimal place to cross, as it led directly to a gap between two defensible hills. The trick was to navigate the river without alerting the Confederates—a desperate plan, but, if executed properly, it had a reasonable chance of success.

Command of the operation, scheduled for pre-dawn October 27, went to Brig. Gen. William Hazen, who chose to divide his 1st Brigade in two. One contingent would include 50 flatboats (each with 25-man crews) to make the initial landing and build the bridgehead. Those flatboats were to follow a larger boat—consisting of about 50 men of the 23rd Kentucky under Lt. Col. James Foy. Hazen’s remaining troops would then cross once the bridgehead was secured.

Among those in the lead boat was Corporal Arnold Brandley, who wrote: “All went well until we passed under a tree that had fallen out from the bank and was still hanging by the roots just high enough to allow the boat to pass under; the order was whispered, ‘Everybody down.’” A sergeant named Reeves tried to jump over the tree, but, Brandley wrote, “was not quick enough and…was swept into the cold stream,” adding that Reeves never cried for help. “[W]e passed on in doubt of whether we would ever again see our comrade.” (They would.)

Spotting a picket fire on the bank downriver, Brandley recalled, “Gen. Hazen sent the word to steer for that light, which we did hurriedly.” Hazen’s order, however, was heard by a Rebel picket, who promptly sounded the alarm, “Fall in, the Yanks are coming!”

With the boat a mere 30 feet from the bank, Brandley noted, “I heard the officer of the guard give the command, ‘Ready, aim, fire!’ One of the oarsmen, an 18th Ohio boy, dropped his oar with a rebel bullet in his arm. We were thoroughly aroused and anxious to fire back, but we remembered our orders….With one of our oars being gone, the boat swung around as if on a pivot.”

Grabbing a collection of willow branches, an officer steadied the boat, allowing the men to hastily disembark and wade to shore. Recalled Brandley:

The rebs were in and about a log house at the edge of what is known as Browns Gap; there was no chinking between the logs, and we could see their movements very plainly. They were trying to organize, but before they were able to do so, we charged on them through the darkness, firing as we went.

The handful of Rebels scattered, but were soon reinforced and staged a counterattack, driving the landing party back to the shore. But reinforced by men of the 6th Indiana and the rest of the 23rd Kentucky, Foy’s men reorganized and charged yet again—“driving the enemy once more through the Gap where they were cooking a large kettle of beef,” Brandley wrote.

Now daylight, the men halted at the kettle, “grabbing for the beef—running hands and bayonets into the hot water, gobbling up the delicious pieces of half-done beef—and around this old kettle the battle of Brown’s Ferry and the charge of the first boat’s crew ended.”

With 17 killed or wounded, the squad did not emerge unscathed. Brandley would later write, amused: “Col. Foy was shot through his new hat. He lamented very much…he did not bring his old hat in place of this one.”

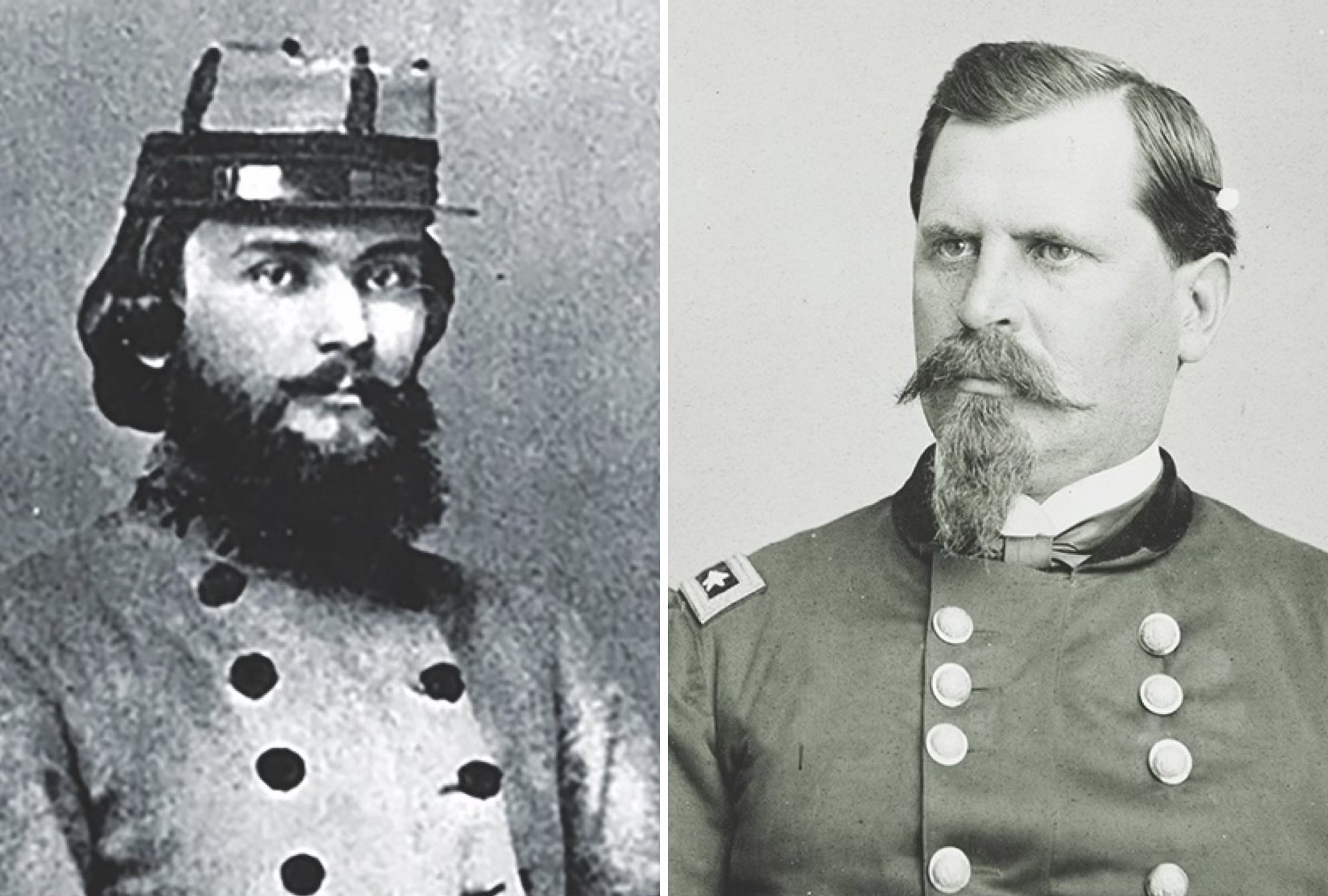

One regiment doing its best to stem the Yankee tide was the 15th Alabama, which had earned notice back in July for its determined Little Round Top fighting at Gettysburg. Wrote Sergeant William A. McClendon:

Our pickets [had] increased their vigilance, so as not to be taken by surprise….[W]e felt sure that we could defeat any attempt to land that the Yankees would make….It was at early dawn when we felt secure in our warm beds, that the cracking of guns began in rapid succession….Our company…hurried to the support of Company ‘B’ in double quick time. We left all our camp equipage, including our tents, oil cloths, blankets, cooking utensils and clothing, except what we had on….

The Confederates, McClendon noted, were soon “contending against great odds, and our companys [sic] deployed and went at them firing volley after volley into their crowded ranks, but there was a whole brigade of them, eighteen hundred strong….[T]hey had landed and gained a foothold so strong that we could not drive them back. We fought at close quarters for awhile.”

Finally, relented McClendon, they were ordered to fall back: “[T]he Yankees were in force below us and our capture for a time seemed a certainty, but we made our way without any confusion, and recrossed Lookout Creek, and took position at the foot of Lookout Mountain.”

As other Union forces arrived, the Yankees soon had control of both hills and could build the bridge. On the 28th, Hooker arrived to officially open the Cracker Line.

The next evening, as Hooker’s corps, now combined with troops from the Army of the Cumberland, marched toward Chattanooga, a Rebel force under Lt. Gen. James Longstreet attacked Brig. Gen. John W. Geary’s rearguard at Wauhatchie Station. After three hours of bitter fighting, Longstreet’s men retreated. There would be more fighting along the way, but within days, the beleaguered Federals in Chattanooga were being reinforced by 40,000 troops—and thankfully resupplied.

Grant, however, still needed control of the city. It would take nearly a month, culminating in a three-day series of battles, before that could be achieved.

Ron Soodalter writes from Cold Spring, N.Y.