Hoping to smash the entire Union Navy, the Confederacy tried to buy the most lethal fleet afloat

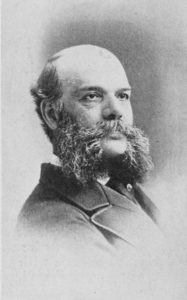

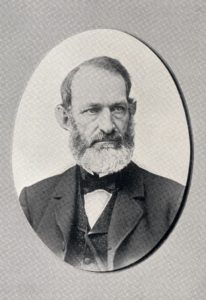

Georgia native James Dunwoody Bulloch was of average height and build, with a slightly receding hairline atop bushy sideburns. However, Bulloch walked big. At night, as he stalked the cobbled streets of Liverpool, England, during the American Civil War, Bulloch’s emphatic footfalls made him sound imposing. The U.S. State Department called Bulloch the most dangerous man in Europe. Rumor had it that the Union was offering a bounty on his head—one reason he took the long way to his flat. But Bulloch, a member by blood and marriage of aristocratic American families, also walked to get lost in thought and rev his creative energies.

As the Confederacy’s European spymaster, Bulloch had a breadth of duties, including buying civilian ships and reconfiguring them into commerce raiders, like CSS Alabama, to prey on Union shipping. Bulloch also oversaw the smuggling of Southern cotton into England and clandestine transport of war materials in the opposite direction by blockade runners. In many respects, Bulloch was the South’s sole source of hard currency.

Fifteen antebellum years serving in the U.S. Navy had conditioned Bulloch to love the sea and to keep abreast of the latest in maritime and military technology. Recent innovations in weaponry, ship design, and propulsion had set his mind racing. It was one thing to perforate and outrun Lincoln’s blockade and to outgun a federal warship in ship-on-ship combat. But what if one could design a vessel so unstoppable as to be able to bring down the entire U.S. Navy?

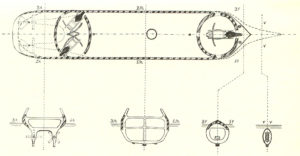

In 1862, after one of his Liverpudlian constitutionals, Bulloch, 39, sat at a table with paper, pencil, and ruler and began drawing a warship. For weeks, he drew and re-drew, always coming back to a topside array, akin to that of the Union’s Monitor, of two revolving gun turrets clad in 10 inches of armor. Along either side of its hull, Bulloch’s imaginary vessel mounted banks of British rifled cannons protected by 4.5” of steel. Around the deck, he pictured Gatling guns able to cram enemy boarding parties into interlocking fields of fire.

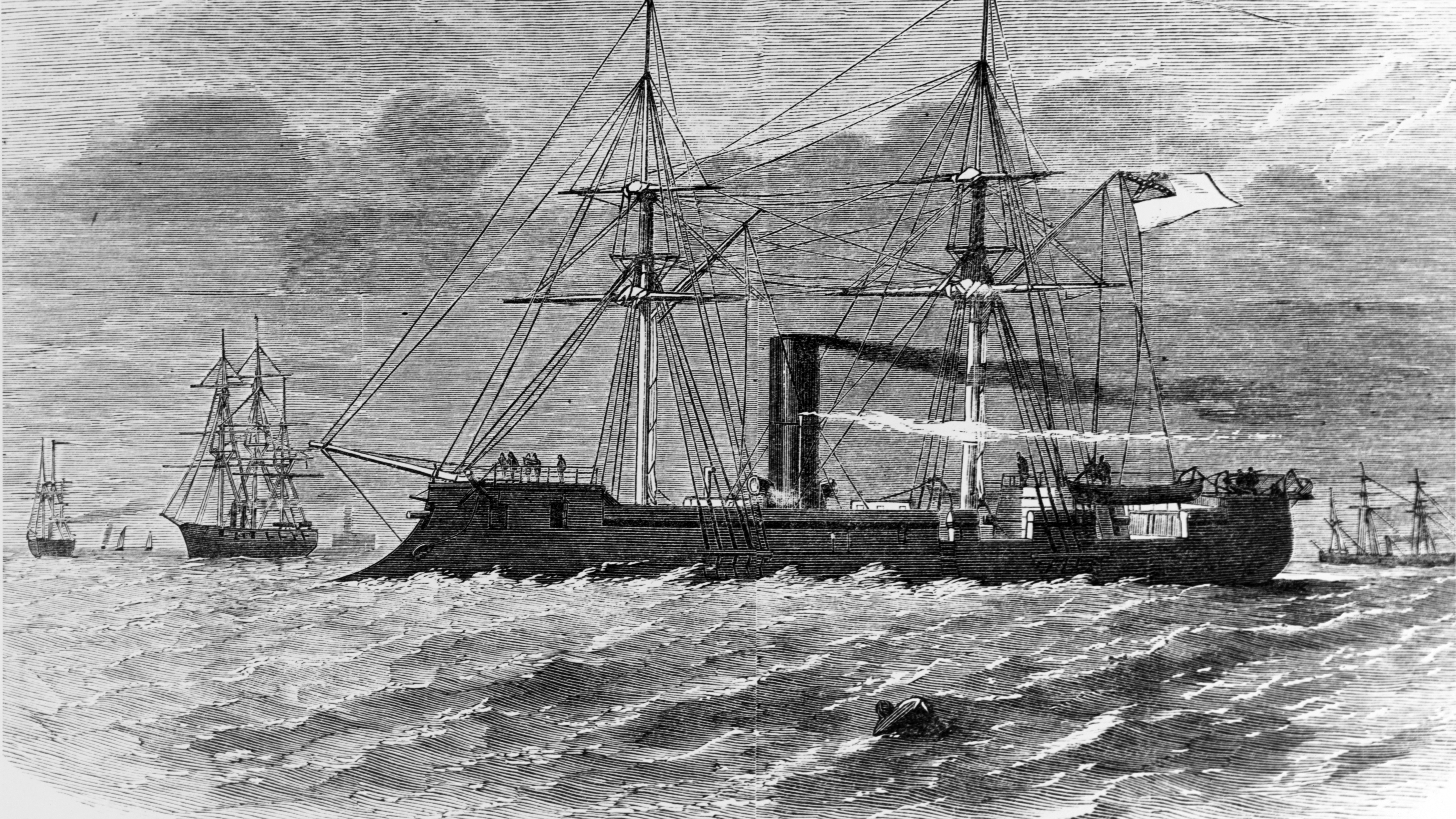

The preliminary design showed a vessel 250 feet long with a beam of 31.5 feet. Two 350-horsepower steam engines would power the 1,358-ton behemoth to speeds exceeding ten knots. Should coal run low—the ship could carry only 90 tons—Bulloch added sails and rigging that extended the ship’s range. At the bow, Bulloch sketched a reinforced wrought iron battering ram below the waterline. The ram was considered essential because naval gunnery seemed unable to pierce the armor protecting the superstructures and gun decks of ironclad ships, but the wooden hulls were left vulnerable to a front-on strike. “I designed these ships for something more than harbor or even coastal defense,” he wrote in 1863. “I confidently believe, if ready for sea now, they could sweep away the entire blockading fleet of enemy vessels.”

If one ram had such potential, Bulloch reasoned to Confederate Navy Secretary Stephen Mallory, imagine what a fleet of the big fellows, escorted by armored wooden cruisers like the Alabama, could accomplish. Mallory liked the way Bulloch’s mind worked, but, on this topic, he and his spymaster sparred. Mallory wanted the rams to have a shallow draft, enabling them to patrol coastal waters and rivers, as the South’s ironclads already were doing. Shallow-draft rams would take a toll on the Union Navy—provided the Union Navy attacked. In contrast, Bulloch saw his rams as globe-ranging hunter-killers, pursuing and destroying Union warships at will, a blue-water role demanding a deeper hull suitable for ocean-going travel. Once his rams smashed the Union Navy, Bulloch posited, the seagoing beasts could invade New York, Boston, Baltimore, and other Yankee ports and lay waste their waterfronts. After a series of letters, Mallory embraced Bulloch’s vision. Soon South Carolina-based blockade runner George Trenholm was smuggling a million dollars in Confederate gold into Liverpool aboard his ships. With the gold came instructions from Mallory to build four rams on the sly. That meant spreading out the project. Bulloch contracted to have the rams North Carolina and Mississippi built by the Laird Shipyard at Birkenhead, across the harbor from Liverpool. Code-named Cheops and Sphynx, another two rams were to be built at Bordeaux, France, by Lucien Arman, a French legislator with ties to Emperor Louis Napoleon III.

Britain and France each had neutrality acts, and each officially recognized the Confederate States of America as a belligerent with certain rights, separate from the North though not quite an independent republic. Britain had reasons for backing the South besides feeding its cotton mills; a smaller United States of America would make Canada less nervous. France, too, had cotton mills—but France also was occupying Mexico, an affront to the Monroe Doctrine. President Abraham Lincoln had made plain that once he defeated the South he would be coming for those French occupiers and their Mexican puppets. France preferred a Confederate border with Mexico to one lined by Union forces.

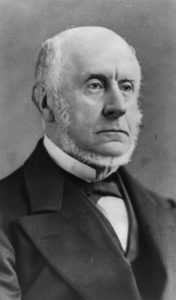

That million in gold ignited a game of dodge and feint between Bulloch and his agents and Charles Francis Adams Sr. and Thomas Haines Dudley, U.S. envoys to Britain, and John Bigelow, U.S. envoy to France. Dudley was the one who sniffed out the rams. As U.S. consul in Liverpool, Dudley apprehended that the Laird yard was much too busy—masses of steel were coming into Birkenhead—and Bulloch in and out of Liverpool too often for a sentient man not to conclude that Confederate money was fueling a shipbuilding boom. One night Dudley’s men scouted the shipyards, spotting the giant hulls. On August 30, 1862, Dudley alerted his federal masters to the rams. “The ribs of one is up,” Dudley reported. “and they have commenced to put on the plates.”

The revelation sent Ambassador Adams into a panic, and rattled the Union government. Based on Dudley’s account of what he had seen, no U.S. Navy ship could withstand the Laird rams, Adams said. He pressed Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston’s subordinates on the ill-advisedness of the matter. In Washington, Secretary of State William Seward told British Ambassador Lord Richard Lyons that Lincoln was prepared, if the rams sailed, to make undeclared war on British commerce.

The latest turns in the two-year-old war between North and South had Britain and France distancing themselves from the Confederacy. Union victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July 1863 seemed to dim rebel hopes for victory. Seward ordered Adams to go public in the British press with Dudley’s evidence about the rams. Coverage casting the ships as a neutrality act violation outraged Britons. Whitehall, hoping to calm Britons’ ire, ordered the seizure of the Alexandra, being built at Liverpool for Confederate service as a commerce raider.

The day after Lee lost at Gettysburg, Dudley reported that Laird had launched the rams into Liverpool harbor. Bulloch had concocted a byzantine deal to mask the ships’ ownership and purpose. A Paris-based, Russian-owned firm, Bravay & Company, was the nominal purchaser. Bravay representatives told the British they were middlemen for the Pasha of Egypt, who wanted the vessels as Nile River patrol craft. The Laird rams actually were to sail to France to be sold to Bulloch. The Russians would earn a healthy commission for their part in the charade.

In September 1863, Adams presented the British with a note stating that if the Laird rams sailed from Birkenhead, “this is war.” On October 10, 1863, armed British sailors from the HMS Majestic seized the British-built rams. Laird sued the Crown, which forcibly bought the rams, renaming them HMS Scorpion and HMS Wyvern. Besides neutralizing Union threats, the British may have had practical reasons for the seizure. The Royal Navy was 90 percent wooden-hulled; Britain and France had ironclads, but nothing in the rams’ league. Both nations had allowed weapons for which they had no defense to be constructed on their soil. Palmerston did not want to run the risk of France obtaining and using the Laird ships. Seizing the rams resolved part of that multipronged dilemma.

Bulloch was in France, trying to stay ahead of events, such as the apparent impending seizure of the second pair of rams. Gettysburg had forced Napoleon III to rethink his attitude toward the Confederacy; the emperor was tilting pro-Union, hoping to parley with the Lincoln administration. Napoleon seemed to know that at Arman’s yards in Nantes the politician-cum-shipwright was constructing two rams, along with corvettes ordered by the Confederacy but represented as being Swedish. A government agent showed Arman proof that the ships were not for the Swedish Navy and that he was close to violating his nation’s neutrality laws. Denmark and Prussia were at war; the pragmatic Arman arranged to sell Cheops to Prussia and Sphynx to Denmark. He was not selling the rams to the South, but he still was violating French law, so he confected fictional buyers in Sweden and the Netherlands for each ship. The French government knew Arman was breaking some law, especially when Danish naval officers began supervising changes to Sphynx—but as long as the rams were not going to the Confederacy, the French did not concern themselves. After all, Arman was a legislator.

Denmark renamed Sphynx the Staerkodder and had a French crew sail the ram to Copenhagen starting on October 15, 1864. Cheops, renamed Prinz Adalbert by Prussia, got a later delivery date. But by the time the Danish ram reached Copenhagen, the Prusso-Danish war had ended. The Danes refused delivery, positioning Lucien Arman for a huge loss. He contacted Bulloch, offering to sell the Confederacy the Sphynx for 373,000 francs plus 80,000 francs for his agents.

Bulloch agreed to Arman’s deal. In coded telegrams ostensibly about teakwood shipments, Bulloch ordered Confederate Navy Captain Thomas Page to take command of the Danes’ ram once it was out of Danish waters. Page’s temporary crew would be the men of the captured CSS Florida, now being held in Europe. Blockade runner City of Richmond would rendezvous with the ram at Belle Isle, an island in the Bay of Biscay, bringing supplies and a permanent Confederate crew. French coaler Expeditif would also be at Belle Isle to fuel the ram. Page’s combat orders would come later.

Bulloch thought he was working in utmost secrecy—until, at a Paris rail station, he ran into a gaggle of young Confederate naval officers with their female companions. The sailors begged to crew on the newly active ram. “It forced me to make a partial confession in order that I might warn them to secrecy and caution,” Bulloch said later.

On January 7, 1865, the soon-to-be-former Danish ram, now christened Olinde, sailed from Copenhagen, listing Page as a passenger. When a gale hit Western Europe’s coast, the heavyweight vessel did not ride the swells, but plunged through, “diving and coming up after the fashion of a porpoise,” wrote Page. The Belle Isle rendezvous occurred as planned. Once the fresh crew replaced the men who had sailed from Denmark, Page commissioned the ram as CSS Stonewall and sailed south. The gale, now full force, was driving waves over Stonewall’s decks bow to stern. Compartments were taking on water, and a leak threatened to flood the bilge. Low on coal, Page put in at A Coruna, on Spain’s northwest coast, on February 2. He sent Bulloch a report on Stonewall’s seaworthiness. Bulloch responded by dispatching an engineer to repair the ram; the man also bore orders identifying Page’s target: He was to cross the Atlantic to Nassau, evaluate the situation at Savannah, Sherman’s supply port in Georgia, and, if indications were good, destroy those facilities and stores. The orders’ wording suggested to Bulloch that if Sherman had burned his way to the Georgia coast, the South already had lost. The storm had so damaged the ram that Page had to limp to the shipyard at nearby El Ferrol for repairs.

John Bigelow learned from American operatives that the ram had left Copenhagen. On January 28, word reached Bigelow in Paris that the ram had been spotted bearing the name Olinde. Determined to find and sink the big vessel, Bigalow alerted U.S. warships across Europe. Spies watched the coast. American agents quizzed Expeditif crewmen. On February 4, Horatio Perry, charge d’affairs in at the U.S. Embassy in Madrid, reported a sighting of a Confederate ram undergoing repairs at A Coruna. The American navy dispatched the frigate USS Niagara from Antwerp and the sloop of war USS Sacramento from Cherbourg. When Stonewall steamed out of El Ferrol, the Americans were to sink it. Sacramento was the same size as Stonewall; Niagara, 100 feet longer. Both had wooden hulls. The Stonewall’s fore turret had a rifled Armstrong cannon that fired a 300-lb. round and in its after turret two 70-pounder rifled Armstrongs. On March 24, Page took Stonewall into the Ferrol estuary, steaming directly at Niagara with both turrets’ guns trained on the Union warship. From 10 a.m. to 8:30 p.m., Stonewall lay near the foe, waiting for Captain Thomas Craven of Niagara to fight. Craven refused to engage. To do so, Craven said later at two courts-martial, would have been suicide. Having survived the day without a shot being fired, CSS Stonewall sailed for Lisbon, Portugal, to refuel. On March 28, Stonewall departed Lisbon, bound west. Union surveillance reported her coming into Nassau, the Bahamas, on May 6. At Nassau, Page learned that Lee had surrendered and that Union forces had captured Jefferson Davis. Broke and low on supplies, Page sailed to Havana, shadowed by the USS Monadnock, a double-turret monitor roughly Stonewall’s length but not its size. Page now captained a ship without a country. Lacking authority to sell a Confederate Navy ship, he spurned Spanish authorities’ offer of $60,000 for the vessel. However, he did need $16,000 to pay his crew. Proffering that sum, the Spanish took control of Stonewall, giving Page and his men every courtesy. In July, the Spanish turned the warship over to American authorities, getting their money back.

Stonewall sailed to the Washington, DC, Navy Yard, where it languished for two years. In 1868, the government decided that selling the ram to Japan’s Tokugawa Shogunate would improve relations with that nation. The Shogun agreed to pay $30,000, plus $10,000 upon delivery. On April 2, 1868, Lieutenant George Brown sailed the former Confederate vessel into Yokohama Bay, arriving amid civil war between the forces of the Emperor and those of the shogun, leader of the Samurai military class. France and Britain were intervening in the conflict with men and supplies. The shogun’s sea and land forces had retreated to Hokkaido, declaring that northernmost Japanese island the independent Ezo Republic, and the city of Hakodate there its capital.

Robert Van Valkenburgh, the U.S. minister to Japan, ordered the ram kept under American control. The emperor’s representatives begged the Americans to release Stonewall. In February 1869, Van Valkenburgh relented. Renamed Kotetsu and now the Imperial Navy’s flagship, the ram had American officers and crew on board to offset shogunate warships’ ranks of French advisers.

On March 25, 1869, at Myako Bay, Ariel Ikunosuke sailed warship Kaiten, flying American colors, up to Kotetsu, at the last moment lowering the Stars and Stripes, raising the Ezo flag, and ramming the Stonewall. The Kaiten carried 300 elite swordsmen assigned to board and capture the ram. As the swordsmen dropped from the attacker’s much higher deck onto Stonewall, Kotetsu’s crew cranked Gatling guns, slaughtering the boarding party. Ikunosuke and Kaiten escaped.

Now dominating Hakodate Bay, Kotetsu proved as unstoppable as Bulloch had envisioned, sinking Kaiten and a second shogunate warship, effectively destroying the Ezo fleet as the crews of a French warship and a British warship looked on. The French vessel took on the French personnel who had assisted the shogun in the Japanese power struggle and sailed away. In 1871, Kotetsu was renamed Azuma, serving until 1888 when relegated to harbor duty. An American in 1908 commented that the old leviathan was still afloat, “peacefully rusting away.” The Prussians never used sister ship Prince Adalbert, which was broken up in 1878. Captain Page moved to Argentina, where his son and grandson saw service in the Argentine Navy, the grandson making admiral.

Excluded as a spy from the post-war amnesty accorded most former Confederates, James Bulloch lived out his life in Liverpool, now and then infiltrating the United States in disguise to visit relatives, including young nephew Theodore Roosevelt.

This story from American History was posted on Historynet.com on January 5, 2021.