The Messerschmitt Me-110 “destroyer” was shot down in droves during the Battle of Britain, but it went on to become World War II’s most successful night fighter.

During the 1930s, the concept of a “heavy fighter” came into vogue. Air combat was still in its formative years, and aircraft designers believed that four-engine bombers with enough guns to make them “flying fortresses” would be unstoppable. Gloster Gladiator biplanes had yet to give way to Supermarine Spitfires and Hawker Hurricanes, so the idea of a large, twin-engine fighter with overwhelming firepower that could both protect bombers and blast a path for them seemed to make sense.

Many pursued the idea: the Dutch with the Fokker G-1, the Soviets with the Petlyakov Pe-2 and -3 and the British with the Bristol Beaufighter. The Americans came up with both the uniquely successful Lockheed P-38 and the useless Bell YFM-1 Airacuda. The P-38 Lightning was a success because from the outset it was intended to be a fighter, though it later undertook other roles, such as reconnaissance. Most heavies were designed as multirole aircraft, which inevitably compromised fighter performance.

Two late-war heavy fighter designs, Germany’s Dornier Do-335 Pfeil centerline-thrust twin and the North American F-82 Twin Mustang, were particularly sophisticated responses to the concept, especially the Do-335. Had the Dornier ever been produced in quantity, it would have been a fearsome weapon.

Initially, Germany’s heavy fighter was to be a fighter/destroyer—Kampfzerstörer, a generic Luftwaffe term (soon shortened to Zerstörer) for an airplane that could be launched to beat back hordes of attacking bombers. The unproductive bomber-escort function of the heavy fighter came later, after the surprisingly shortsighted Germans realized they were going to have to go to war with Britain but didn’t have bomber escorts with the range to cross the Channel.

The hammer in the Germans’ heavy fighter toolbox was the Messerschmitt Me-110, a frequently maligned design that in fact was an effective weapon from the beginning of Adolf Hitler’s Polish blitzkrieg until the very last days of the war. “Oh, that’s the bomber escort that was so lousy it needed an escort itself,” somebody is sure to respond. Well, yes, just as Hurricanes needed Spitfire escorts while they concentrated on shooting down Heinkels, or bomb-laden Republic F-105s over Vietnam were happy to have McDonnell Douglas F-4s hanging around.

The missing ingredient in the heavy fighter formula was maneuverability. Nobody could roll or turn an airplane as fast as a single-engine fighter when it had two big V12 engines weighing down its wings. And to make matters worse, the Me-110 had particularly heavy controls. Even the strongest pilots tired rapidly during serious maneuvering. “Pulling out of a dive required the strength of an ox,” said one Luftwaffe test pilot. “It was inconceivable to me how such an escort fighter could ever have gone into production.”

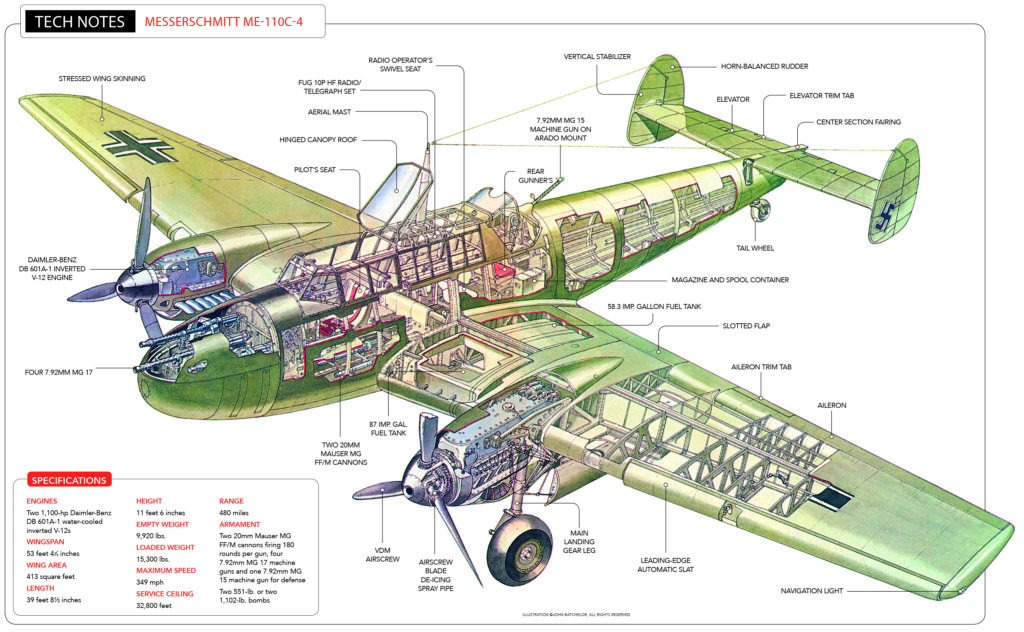

Though the 110 had substantial firepower in its nose—typically four 7.92mm machine guns and two 20mm cannons, with a variety of even heavier weapons hung on later marks—it was too often pursued from astern, an area covered by a single hand-operated machine gun. The ultimate Me-110, the G model, got a brace of more effective rapid-fire twin Mauser tail guns.

During development of the Bf-110 (as all subtypes designed for the Bayerische Flugzeugwerke prior to July 1938 were designated), test pilot Hermann Wurster flew the prototype in demonstration dogfights against Ernst Udet, in a Bf-109. Perhaps the 110 was carrying minimum fuel and no ordnance, because it reportedly could fly just as tight a turn as the single-seater and refused to stall even during the steepest turns. Bf-109/110 dogfights were also staged for important foreign visitors and potential export buyers, with German national aerobatic champion Willi Stör flying the unbeatable 110, which he proclaimed was the best twin-engine aerobat on the planet. Apparently, somebody had a thumb on the scale.

Willy Messerschmitt was never a popular designer among his peers, and Erhard Milch, who was in charge of aircraft production for the Luftwaffe, outright hated him. Messerschmitt was only allowed into the competition for the proposed

mid-1930s heavy fighter contract because of his influential friend Udet, the World War I ace and aerobatic champion, who at the time was in charge of Luftwaffe R&D. Some historians even believe the 110 was intended to fail from the outset, and that when Milch approved the unpromising project in 1934, he meant for the 110 to sink Messerschmitt once and for all.

Messerschmitt’s brief initial Bf-110 design concept was an F-82-style twin 109 with two enlarged fuselages. He soon switched to an all-new design—only the second military airplane he had created—with a slender, tapering fuselage, twin tails and a long, protruding canopy. The substantial greenhouse and cockpit would become an asset when the initial two-man crew—pilot and rear gunner/radio operator—grew to three as the 110 found its niche as a night fighter and needed space for a radar operator.

The actual functional designers of the 110 were project chief Robert Lusser and engineer Walter Rethel; Messerschmitt himself was still busy with the Bf-109. His company was also going through a management reorganization, which led to a lack of critical oversight during the design’s early stages.

First flight took place in May 1936, with Bayerische Flugzeugwerke chief pilot Wurster in the cockpit. Many sources claim that Rudolf Opitz was the pilot, but Opitz’s logbooks, today in the possession of his son Michael, show that he was not at Augsberg on that day, nor did he have a multiengine rating at the time. Opitz would go on to make the first powered flight of the horrifically dangerous Me-163 rocket plane.

As was his wont, Messerschmitt had ignored the Reich Ministry of Aviation’s request-for-proposal provisos and followed his own path in engineering the Bf-110. Two of his guiding principles were lightness in aid of the highest possible performance, and simplicity to support ease of construction. It remained a concern throughout the production life of the airplane, though, that two 109s could be built for the cost of a single 110.

Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, ever the romantic, loved the idea of swarms of gaudily painted Zerstörers carving their way through the skies. He considered the Me-110 more important than the 109 and bled off some of the best single-seater pilots to man his questionable fleet, which distressed the Luftwaffe. The paint lived on, though. The shark’s-teeth motif of II Gruppe, Zerstörergeschwader (destroyer wing) 76, first seen over France in 1940, was copied by the Royal Air Force’s No. 112 Squadron for its Curtiss Tomahawks and quickly adopted by the American Volunteer Group “Flying Tigers” as well. The design passed into history as Flying Tiger leader Claire Chennault’s invention.

In an odd precursor to the stolen-MiGs episodes of the Cold War, in May 1939 an ex-Luftwaffe pilot, Franz Öttil, stole an Me-110 from Augsberg and tried to fly it to France. Öttil had been cashiered from the air force for flying a biplane trainer into the roof of his family’s farm during a buzz job. He successfully flew the Messerschmitt to a nearby soccer field, where his brother Johann was waiting with gas cans. With the airplane refueled, the pair took off, bumbled into heavy fog and died when they hit a low hill in the Vosges range, in eastern France. Whether they were to be paid by the French, who evidently had initiated the theft, or simply wanted to migrate westward has never been determined.

A far more notorious Me-110 heist was Rudolf Hess’ jaunt to Scotland in May 1941, a mission he had carefully planned for almost a year. At the time, Hess was Hitler’s deputy führer and a moderately experienced pilot. Hess had first asked Messerschmitt for a 109, saying he wanted to be combat-capable if needed, but Willy thought that was a bit much. Hess was able to requisition a 110 for his occasional personal use, and over time he quietly had it equipped with long-range tanks, oxygen gear and special radios. Hess imagined that he could fly to the British Isles, negotiate personally with the government and effect a negotiated peace that would spare all concerned a great deal of trouble. He bailed out of his 110 near Glasgow and was promptly arrested, jailed and four years later sent to the Nuremberg trials, where he was sentenced to life imprisonment. So much for personal diplomacy.

Initially, all seemed to go well for the Me-110 when the war started. Over Poland and then Norway, 110s met little opposition and ranged freely in a ground-attack role. Both Junkers Ju-87 Stukas and Zerstörers were the Wehrmacht’s flying artillery. And both Stukas and Zerstörers found their nemesis in the RAF.

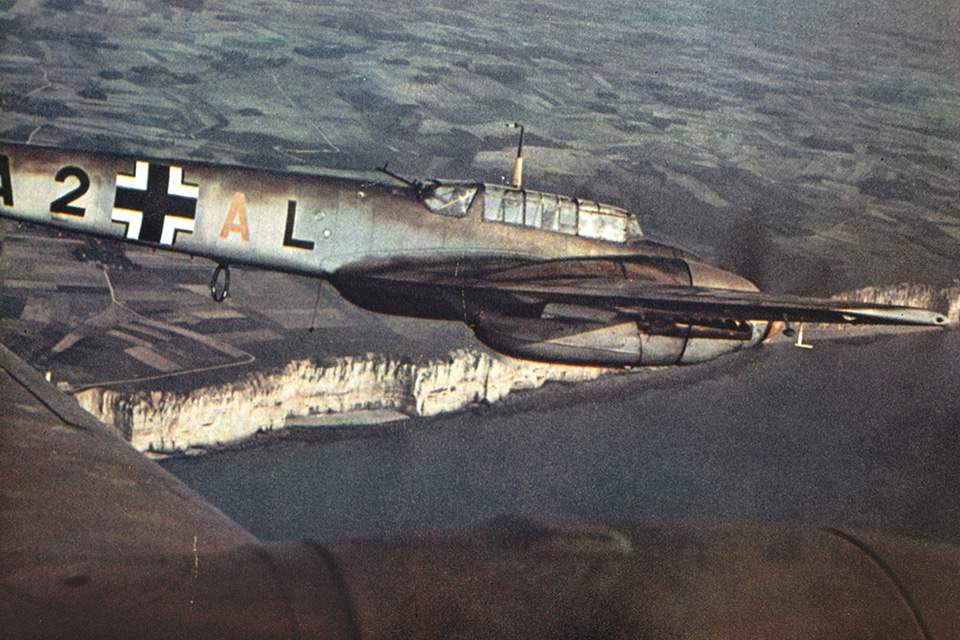

During the Battle of Britain, the Me-110’s main flaws as a fighter quickly became apparent. In British aviation historian Martin Windrow’s words, “It was easily identifiable from long distances; its acceleration and speed were insufficient to allow it the luxury of avoiding combat; it was sluggish in evasive maneuvers; its turning circle was wide; and with its large wing and tail surfaces, it presented a good target….The destroyer became the destroyed.”

The Luftwaffe began the Battle of Britain with 237 Me-110s. By the end of that fight, it had lost 223, though of course numerous replacement units had joined the several squadrons involved. (By the end of the war, 6,170 Me-110s had been manufactured.)

The 110’s only real defensive maneuver was to form a broad circle and tail-chase each other until, they hoped, some 109s showed up. Each Zerstörer could in theory cover the one in front of it, though in reality Spitfires sniped at the 110s from outside the circle, since the Messerschmitts couldn’t really maneuver and their rear gunners provided little protection.

For several good reasons, the Me-110 ultimately found its niche as a night fighter. Unlike most Luftwaffe aircraft, it was equipped for serious instrument flight, which could be a necessity even in clear weather, on moonless nights. Its enormous cockpit could accommodate a radarman and his electronics in a middle seat, with room left over for the Me-110’s fiercest weapon, the upward-firing twin 20mm MG FF/M cannon called Schräge Musik (slanted music). The added weight was substantial, though: A fully equipped Me-110G night fighter weighed more than 10 tons—almost twice the weight of the original 1938 Bf-110B.

The Germans had done considerable work in the mid-1930s in developing effective cavity-magnetron radar, though the British are rightly credited with having improved the cavity magnetron to the point of being practical for internally mounted, streamlined airborne radar. The Germans used cavity magnetrons for their excellent Wurzburg fire-control radar to direct flak guns, but the airborne Telefunken sets in Me-110s and other night fighters all used draggy external stag’s-antlers antennas.

The Schräge Musik guns were fixed, and the only aiming consisted of a 110 pilot ghosting under an RAF bomber from astern. Usually he maneuvered to point the cannons at the fuel tanks in the wings, as a clean centerline belly shot could set off an Avro Lancaster’s bombload, which would be as fatal for an attacking Messerschmitt directly under that cataclysm as it would be for the bomber.

A two-second burst of twin 20mm fire typically was enough to finish a Lanc, and the Brits literally never knew what hit them. The Schräge Musik cannons often fired special high-explosive rounds with three times the blast of a normal 20mm HE round. It took nine months for the RAF to figure out where the Schräge Musik attacks were coming from, since no tail gunners survived who might have seen a 110 quietly sliding underneath their aircraft. It has been called one of the major intelligence debacles of the European air war because a captured Luftwaffe mechanic had revealed its existence early on during interrogation but was ignored. Examination of a damaged Me-110G-4 that force-landed in Switzerland in April 1944 finally revealed the slanted guns.

Schräge Musik was so effective that in February 1945 Me-110 pilot Heinz Wolfgang Schnaufer, history’s highest-scoring night fighter ace, shot down seven Lancasters in a single night and then simply quit. “They seemed to be lining up to be shot down,” he said. “I just had to stop after the seventh one. I was tired of the killing.” It was effectively the 110’s swan song, with the war in Europe ending less than three months later.

After the war, Royal Navy test pilot Eric “Winkle” Brown was one of the few Allied pilots to fly an Me-110. The Battle of Britain, he later wrote, “was to lead to a widespread belief that it was an unsuccessful design. This was in fact far from the case.” Brown pointed out that the 110 was never intended to be used “other than in conditions of local Luftwaffe superiority if not supremacy.” The 110 could effectively use its enormous firepower against another aircraft “only if it could employ the element of surprise or if it encountered an unwary novice.”

A German Me-110 pilot commented: “The 110 was a safe, easy airplane to fly, but it was slow like molasses. And it could not stay in the air more than an hour and a half before we had to get back. What if we encountered Spitfires? In a 110? Get the hell out of there. Get away.”

No account of the Me-110 is complete without a mention of its intended successor, the Me-210. Unfortunately for the Luftwaffe, the 210 was one of the worst designs to ever be committed to combat by any air force.

The Luftwaffe had asked Willy Messerschmitt to come up with an upgraded 110, but as with the original Bf-110, Messerschmitt ignored the Ministry of Aviation’s specific request for proposal and designed an entirely new airplane. He and his engineers got the wing profile totally wrong, made several critical production errors that created a weak after-fuselage and empennage, and came up with a short-coupled planform that put the props well ahead of the nose of the airplane, which apparently contributed to its extreme longitudinal instability.

The Me-210 and the concurrent Heinkel He-177 were such disasters and the wartime pressures so great that in November 1941 Luftwaffe Director-General of Equipment Udet put a pistol to his head. He was succeeded by Messerschmitt’s archenemy Erhard Milch, who certainly did the 210 no favors. Udet had written a famous memo to Willy Messerschmitt that he might as well have titled, “Hey, pal, it’s not rocket science.” In his constant pursuit of lightness, Messerschmitt had so weakened the 210’s landing gear that Udet wrote: “One thing, dear Messerschmitt, must be made clear between us, there must be no more losses of machines in normal ground landings as a result of faulty undercarriage. [Landing gear] can hardly be described as a technical novelty in aircraft construction.”

It took nearly two years for Messerschmitt to accede to test pilot Hermann Wurster’s insistence that the 210 needed a longer fuselage for better stability and takeoff/landing handling. By then it was too late. The 210 loved to snap and spin in a traffic pattern while turning with gear and flaps down. When Me-110 pilot Johannes Kaufmann was sent to a training airfield in Germany to transition to the 210, he arrived overhead to find the base littered with “crashed airplanes scattered around the airfield,” obviously new and recognizable as Me-210s.

In March 1942 Willy Messerschmitt was ordered to kill the Me-210 and return to building Me-110s. His company had lost the equivalent of $1.85 billion in today’s dollars on the 210 program and had almost gone out of business. (Milch must have been delighted.) But Willy immediately began development of the Me-110G, the final mark of the airplane (an Me-110H was planned but never built). The Me-110G-4 was the definitive version and the ultimate 110 night fighter. It had 1,475-hp DB 605B engines, but the stag’s-antlers radar antenna made it barely 30 mph faster than a Lancaster—just enough speed to slowly overhaul a bomber but with little grunt to spare.

Most Me-110 night fighters were lost to midair collisions and German flak. Few were downed by RAF gunners. Eighty percent of Lancaster tail gunners didn’t even return fire when attacked, since they never saw their adversaries. (The night fighters didn’t use tracer rounds.) At one point, the victory-to-loss ratio was 30 RAF bombers downed for every Me-110 lost.

The Me-110G-2 that Winkle Brown flew is today one of the only two intact and original 110s in existence. It is on display at the RAF Museum at Hendon, in North London. The other example, an Me-110F-2, is in Berlin’s German Museum of Technology. A third, displayed as an Me-110G-4, is owned by a Danish group in Gilleleje, about 40 miles north of Copenhagen. It is actually a restored assemblage of parts from a variety of 110s.

The Me-110, a workmanlike killing machine, was not particularly attractive, glamorous or technologically advanced. By the end of the war, it was an archaic mid-1930s design—along with the Heinkel He-111, Junkers Ju-88 and Boeing B-17, one of the oldest multiengine airplanes still in combat. And as is so often the case, one of the more consequential World War II combat aircraft has barely survived.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson suggests for further reading: Willy Messerschmitt: Pioneer of Aviation Design, by Hans J. Ebert, Johann B. Kaiser and Klaus Peters; Messerschmitt Bf 110 at War, by Armand Van Ishoven; Bf 110 vs Lancaster: 1942–1945, by Robert Forczyk; and Duel Under the Stars, by Wilhelm Johnen.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!