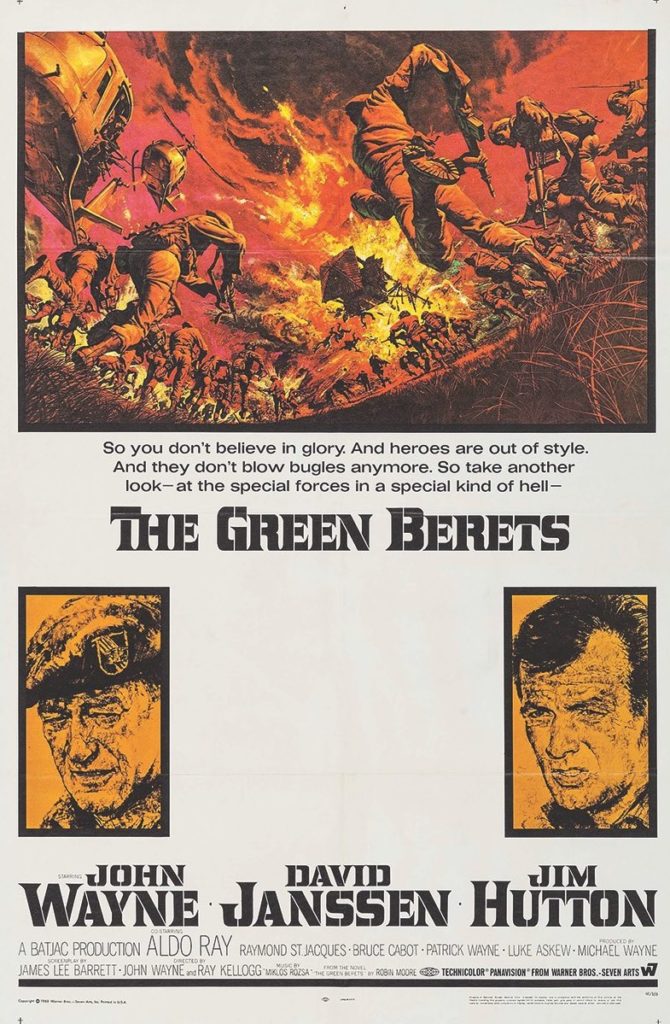

Admittedly, the 1968 film The Green Berets is not John Wayne’s best acting or even his best war movie. The “Duke” was too old and fat to be traipsing around on secret missions in the Vietnamese jungle—portrayed in the film by Georgia yellow pines. Still the film remains an important depiction of the Vietnam War because it was one of the first filmed during the fighting and, like the 1965 book with the same title, it is based on actual events.

When author Robin Moore arrived in Vietnam in January 1964, most Americans were barely aware of the war. It had been only a few months since the November assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and South Vietnamese President Ngo Dinh Diem. The first ground combat troops, the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, wouldn’t land at Da Nang until March 1965. At the end of 1963, about 16,000 U.S. troops were in-country, far below the peak of 435,000 in 1969. The U.S. force in 1964 consisted primarily of military advisers, mostly U.S. Army Special Forces, favorites of Kennedy, who authorized those soldiers to distinguish themselves from the rest of the Army by wearing green berets.

Moore, a bomber gunner in World War II, wanted to tell their story—as only one of them could tell it. He had pulled strings with a fellow Harvard alumnus, Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, to embed himself in the Green Berets as a reporter.

Hoping to weed him out, Army brass insisted that Moore first go through the Special Forces qualification course at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He trained for a year and at age 37 became the first civilian to make the cut. As Moore wrote in his book: “These Special Forces men for the first time accepted an outsider—and a civilian at that—as one of their own.”

None of this, however, prepared him for what was to come. “It was pathetic how much I still had to learn in the vicious, no-quarter jungle war in Indo-China,” he admitted in the first chapter of his book.

In 1964 the South Vietnamese government supported by the United States was coup-prone, infested with communist sympathizers and considered unreliable. To fight the Viet Cong insurgency, U.S. Green Beret advisers manufactured their own combat forces from dissident backcountry minorities—Montagnard hill tribes, Buddhist Hoa Hao, Nung (ethnic Chinese) and Cambodians. Most of the American military involvement was classified information.

“The Basic Truth”

To placate the Army, Moore agreed to cast his book as fiction but explained to readers, “I changed details and names, but I did not change the basic truth.” The novel is written in the first person with Moore as the narrator.

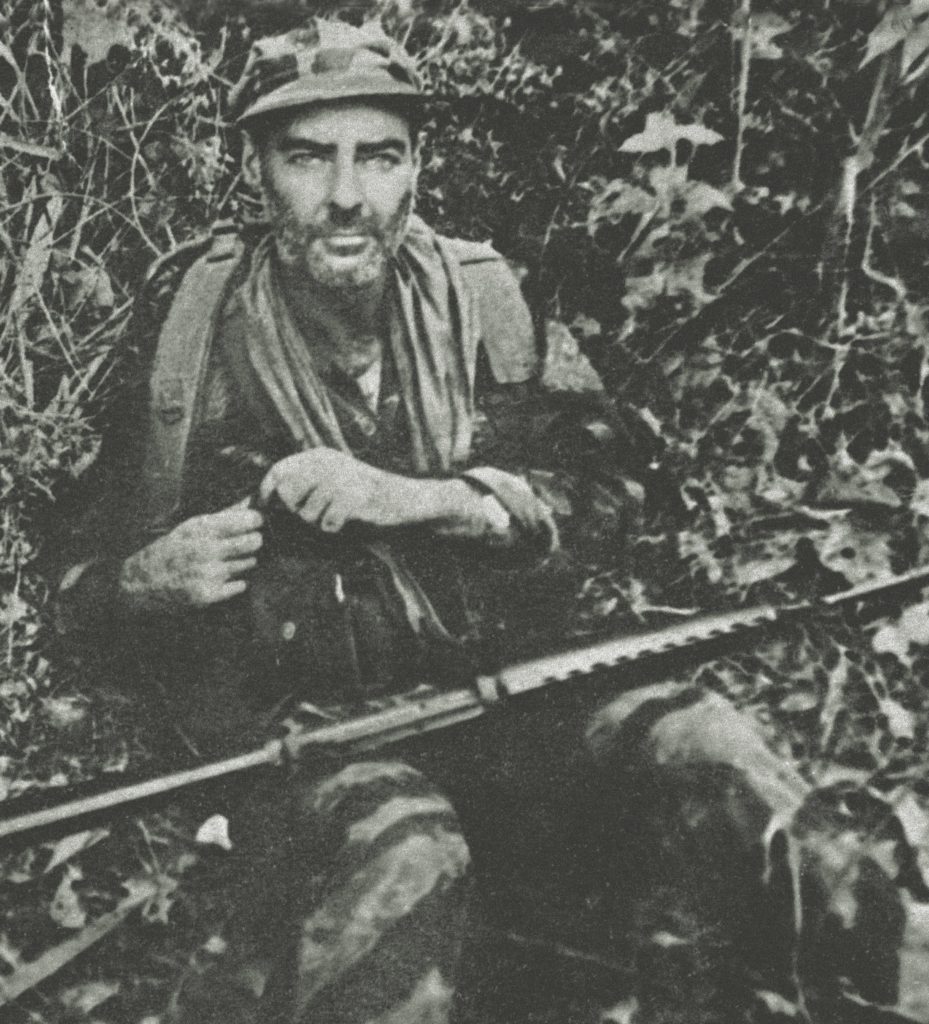

Capt. Steve Kornie, a character in the book, was actually Capt. Larry Thorne (pronounced THOR-nee), a native of Finland. Born Lauri Törni, he had fought Soviet troops who invaded Finland in a territorial dispute during the Winter War of 1939-40. In World War II, Törni joined the hardcore Nazi Waffen-SS paramilitary forces and battled the communists again in 1941 when Finland became a co-belligerent with Germany’s Third Reich in the fight against the Soviet Union. Thorne’s association with the Nazi regime and its ideology remain controversial to this day.

Postwar Törni made his way to the United States in 1950, was granted legal permanent-residence status by the U.S. government, anglicized his name and joined the U.S. Army in 1954. He became a private in the Special Forces, rose to the rank of captain by 1960 and was sent to Vietnam in January 1964. Describing his novel’s Capt. Kornie (Thorne), Moore wrote that “fighting, especially unorthodox warfare, was what he lived for.”

Thorne was assigned to Chau Doc province in the Mekong Delta—arriving around the same time as Moore—on a six-month tour as commander of the 7th Special Forces Group’s Detachment A-734, which consisted of two American officers and 10 noncommissioned officers. The detachment had established observation posts at Chau Lang in the Viet Cong-controlled Seven Mountains sector and ran ambushes along the Cambodian border. The Americans also recruited locals to form militias for village defense, built schools and provided medical services.

The Viet Cong attacked the Special Forces camp a dozen times, raining so many mortar rounds from the surrounding hills that the Green Berets started calling Chau Lang “Little Dien Bien Phu” a reference to a much larger, but also poorly sited base that Vietnam’s French occupiers lost to a communist-led independence movement 10 years prior. As early as February 1964 Thorne reported plans to move his camp “to a better tactical location.”

On April 14, Detachment A-734 set out for a Special Forces camp at Tinh Bien (“Phan Chau” in Moore’s book), next to South Vietnam’s Vinh Te canal paralleling the border with Cambodia. Its mission was to support four companies of Vietnamese and Cambodian militiamen organized into Mobile Strike Forces, U.S.-trained units that conducted reconnaissance patrols, raids and other activities inside enemy territory.

The four companies at Tinh Bien totaled more than 600 “strikers,” although some were of questionable loyalty. Thorne briefed his headquarters: “The VC has penetrated the strike force due to inadequate security checks of personnel.”

Tinh Bien was situated on a rise surrounded by rice paddies, its perimeter packed with sandbags and laced with barbed wire. Machine guns were placed at the corners. When Moore arrived in mid-May, the camp was less than three-quarters complete. In the cement-block command post, Thorne said to Moore, as relayed by Kornie in the book, “We are not ready for attack, so it probably comes soon.”

Master Sgt. Murray Eccleton, the team’s sergeant, told Moore that the Viet Cong made ladders to cross over a base’s barbed wire perimeter in an attack and use as stretchers after the battle. Eccleton added that the Viet Cong also made plenty of coffins because it improved morale. He then delivered a quip that became famous after it appeared in the book and the movie: “The VC fight better when they know they’re going to get a funeral and a nice wood box if they’re killed.”

Thorne expected the Viet Cong would cross the border from their Cambodian lair and attack. The Special Forces captain told Moore, who transferred his words to Kornie: “If we try to hit their buildup on our side of the border they only got to run a hundred meters and they’re back in Cambodia where we can’t kill them. Even if we go over after them, they pull back to their big camp where we get zapped and cause big international incident.”

Surprise Attack

Also in the area was an armed force of ethnic Cambodians, the Khmer Kampuchea Krom. Americans called them the KKK. Many joined with U.S. Special Forces in battling the Viet Cong, but some roamed around as essentially bandits who took whichever side was paying best at the moment and would kill anyone, even Buddhist monks, for money.

“Three days ago I was leading a patrol in KKK area,” Thorne/Kornie said. “We find the monks. They are lying on the trail, each has his head under his left arm. The KKK got them and their gold.”

Thorne came up with an idea that would rid him of both foes: the Viet Cong across the canal in Cambodia and the KKK bandits.

He sent out a patrol led by his second-in-command, 1st Lt. Burton G. Smith (“Lt. Schmelzer” in the book), to meet with the bandits. Smith radioed back that the local bandit chief had accepted Thorne’s offer of $10 per man plus some weaponry, half now and half on completion, if the KKK men would circle around to the north and cross a canal bridge over to the Cambodian side of the border to monitor Viet Cong traffic. Thorne sent 100 Cambodian strikers over the border as well, literally behind the KKK’s back, which put the bandits between the strikers at their rear and the Viet Cong to the front. In the book Moore plays with names and distances, calling the canal a river and hamlets villages, but he makes the general strategy plain.

Thorne then led Vietnamese strikers to a rendezvous with Smith’s detachment outside the Viet Cong village. Together they sprang a surprise attack. There was only desultory return fire, but within moments a battle erupted where the retreating VC ran into the KKK, who were trapped against Thorne’s 100 Cambodian strikers. In the ensuing three-way crossfire only the Cambodian strikers were free to move, which they did—back over the border by daylight, having left the KKK bandits and VC guerrillas to kill each other.

“If a battle across the border is reported I think Saigon would accept the proposition that I paid a bunch of Cambodian bandits to break up the VC in Cambodia long enough to make my camp secure,” Thorne/Kornie said.

Moore’s book has several VC battalions counterattack and all but overrun “Camp A-107,” his stand-in for Detachment A-734. The field reports for the real Green Beret detachment, however, make no mention of such a major action before the unit rotated out in mid-June. Moore seems to have based his battle scene on another Special Forces firefight at the other end of South Vietnam a few weeks later. He was not in that area but certainly would have heard of the battle as it quickly passed into Green Beret lore.

On June 6, 1964, a dozen Green Berets of Detachment A-726, 7th Special Forces Group, led by Capt. Roger H.C. Donlon, choppered to Camp Nam Dong, in a highland valley of Thua Thien province northwest of Da Nang. The camp, close to the borders of Laos and North Vietnam, protected 5,000 inhabitants of nine villages in the valley. Donlon’s detachment was sent there to advise the South Vietnamese camp commander, provide additional protection and give aid to the villagers.

“The VC Are Coming”

The camp dominated the intersection of two VC infiltration routes. By July 4 weekend, Donlon could feel trouble brewing. “We had known that the Viet Cong might attack at almost any time,” he wrote in a first-person account for The Saturday Evening Post published on Oct. 23, 1965. “But that weekend, the threat of attack seemed to have become much greater.”

On patrol Saturday night, July 4, Spc.4 Michael Disser radioed the camp: “The villagers are scared, but they won’t tell me or my interpreters why.” The same day Spc. 4 Terry Terrin’s men found two village chiefs murdered. On Sunday a quarrel between the camp’s 300-odd South Vietnamese strikers and the Americans’ Nung security detail escalated into a brief shootout, which Donlon believed was prodded by Viet Cong who had infiltrated the ranks.

Years afterward it was learned that a third of Nam Dong’s Vietnamese troops, including their commander and intelligence officer, were communist sympathizers, some with orders to murder their compatriots in their sleep before the attack.

That night Staff Sgt. Merwin “Woody” Woods, the team heavy weapons man, wrote home, “All hell is going to break loose here before the night is over.”

Donlon told his team sergeant, Master Sgt. Gabriel L. “Pop” Alamo, “Get everyone buttoned-up tight tonight, the VC are coming. I can feel it.” Donlon looked at his watch—2:26 a.m., Monday, July 6—and just then an enemy mortar dropped a white phosphorus incendiary round on the roof of the mess hall. The fireball had “14,000 different-colored flames shooting out of it,” Woods said in Donlon’s account for the Post.

With deadly precision the enemy hit the camp command post, dispensary and supply room. In the radio bunker Sgt. Keith Daniels managed to get off a partial message to Da Nang: “Request flare ship and an air strike…We are under heavy mortar fire.” He saw the mortar round explosions coming his way as the enemy crews adjusted their range to get closer to the camp. Daniels barely got out of the bunker before it was hit.

In the light of the burning buildings, infiltrators could be seen moving inside the camp. Medic Spc. 5 Thomas L. Gregg shot six of them just 20 yards outside the burning dispensary, and Sgt. 1st Class Thurman R. Brown, dodging explosions to get to his mortar pit, found two enemy soldiers atop its ammo bunker. He shot the VC and jumped into the pit, yelling, “Illumination rounds!”

The light from Brown’s parachute flares revealed a landscape that filled the Americans with terror. “Hundreds of men were moving in on the camp,” Donlon recalled. “They were the main assault force of the two reinforced VC battalions—800 to 900 guerrillas—that had ringed Camp Nam Dong in the night.” Disser, manning another mortar pit near the camp’s main gate, called that scene “the most frightening sight of my life.”

The attackers had overwhelmed the Vietnamese defenders in the outer perimeter trench and were closing in on the Special Forces compound. “They were at the inner perimeter barbed wire,” Donlon wrote. “Our mortar and automatic-weapons fire made them keep their heads down and move with caution.”

Once the VC were inside the wire, the Green Berets’ five mortar pits, spaced around the inner perimeter, were the only remaining American-controlled territory in Nam Dong. Donlon had to hold his men together until air support arrived. “We had been fighting for almost an hour,” Donlon noted. “It was only 32 miles to Da Nang. Where was the flare ship? Where was the air strike?”

A “Bedlam of Bursting Grenades”

John Houston, a specialist 4, took cover in an excavation where a new command post was to be built and held off the enemy with grenades and his M16 rifle. Trying to reach him, Donlon was hit by shrapnel from a mortar blast and wounded in three places. Calling for fresh ammunition, Houston held out until his position was overrun and he was killed.

The enemy “bombarded us with grenades in volleys—five, six, seven at a time,” Donlon said. A grenade went off nearly at the feet of his executive officer, 1st Lt. Julian “Jay” Olejniczak, and broke bones. “He carefully tightened his boot laces and tied them securely around his bare ankle, hoping to stop the bleeding and keep the bones together,” the captain recalled.

An adviser with the Australian Army Training Team, Warrant Officer Class 2 Kevin Conway, took a hit between the eyes. He was Australia’s first official battle death of the war.

“The bedlam of bursting grenades was too much,” Donlon wrote. “In desperation we were picking up grenades and throwing them out of the pit before they could go off.”

The American perimeter was stretched too thin. On his way to ordering one of the mortar crews to pull back closer to the rest, Donlon was hit again: “There was a shrapnel wound about the size of a quarter in my stomach.”

Alamo, the Special Forces team sergeant, was hit in the face. As Donlon helped him out of the pit, a mortar round killed the sergeant outright, and Donlon was wounded yet again. That didn’t stop the captain from hefting the mortar and carrying it to a new position in a pile of cinder blocks, effectively the new camp command post. Donlon then moved throughout the stressed perimeter throwing grenades, inspiring his men to fight on.

The Nung mortar crewmen were all wounded. “Come on, you fellows are going to be all right,” Donlon told them. “You can still fight. Here’s your weapons. Cover me.”

“We used to argue in training about whether it was wiser to lie to your men when they were taking heavy casualties,” he pointed out in the Post article. “There are two schools of thought. I decided that with these men, the bitter truth would make them fight harder.”

The beleaguered Green Berets and their Nung companions held out for an hour and a half. A few minutes after 4 a.m., a U.S. Air Force plane arrived and lit up the battlefield with flares. “It must have discouraged the VC,” Donlon surmised, “for little by little their firing tapered off. A flare ship is usually followed by an air strike, and they knew it.”

Before the bombs could fall, a voice from a megaphone threatened in Vietnamese and then English: “We are going to annihilate your camp. You will all be killed!” Brown answered with 10 mortar rounds on the spot, ending the discussion.

At dawn the Viet Cong pulled out, leaving behind more than 50 bodies. It was assumed that many more had died. A striker who was taken prisoner and escaped reported that every second or third VC fighter had been wounded, and the battalion commander was killed. Team A-726 had two dead (plus the attached Australian adviser), and all but three wounded. Additionally, 58 of the strikers were dead and 57 were wounded by the VC—or by American fire since many had fled to join the enemy.

A post-action survey team counted about a thousand mortar craters on the site. “The fact that the camp held out against such a determined attack,” an American report stated, “makes this action a definite victory over the Viet Cong.”

True events vs. The Movie

For their heroics during the Nam Dong attack, Alamo and Houston were posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the U.S. Army’s second-highest valor award. Four Silver Stars and five Bronze Stars were presented to survivors of the battle.

On Dec. 5, 1964, in a White House ceremony attended by all nine of the other survivors, Donlon was awarded the Medal of Honor by President Lyndon B. Johnson—the first of 262 Medals of Honor awarded for the Vietnam War. Donlon retired in 1988 as a colonel.

Everyone in Thorne’s Detachment A-734 survived that tour, but all were wounded. Thorne was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Bronze Star. On his second tour, he served with Military Assistance Command Vietnam, Studies and Observations Group, a covert organization of elite troops who carried out reconnaissance missions and raids in Laos and Cambodia.

Thorne was commanding a secret mission in Laos on Oct. 18, 1965, to locate VC positions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail when his helicopter crashed during bad weather in a mountainous section of Quang Nam province, not far from Nam Dong. All aboard were killed. Thorne received the Legion of Merit and Distinguished Flying Cross as well as a posthumous promotion to major. His remains were found in 1999 and buried at Arlington National Cemetery in a joint grave with other members of the chopper crew.

Moore dramatized the events at Tinh Bien and Nam Dong for effect in what one of his characters called “plausible deviations from the truth.”

The Special Forces “Battle of Phan Chau” made up only the first couple of chapters in Moore’s book, but it served as the first half of the Wayne film. However, the character Moore based on Thorne, “Steve Kornie,” didn’t make an appearance in the 1968 movie.

Moore, who died in 2008, saw his book become an immediate New York Times bestseller with more than 3 million copies sold. By the time the movie premiered in June 1968 American attitudes about the war had changed drastically. The film was met with scorn from critics but turned a profit within three months.

Don Hollway wrote “The Lost Battle of Lima Site 85” in the January 2021 issue. He lives in central Pennsylvania.

This article appeared in the June 2022 issue of Vietnam magazine.