Terms of Agreement

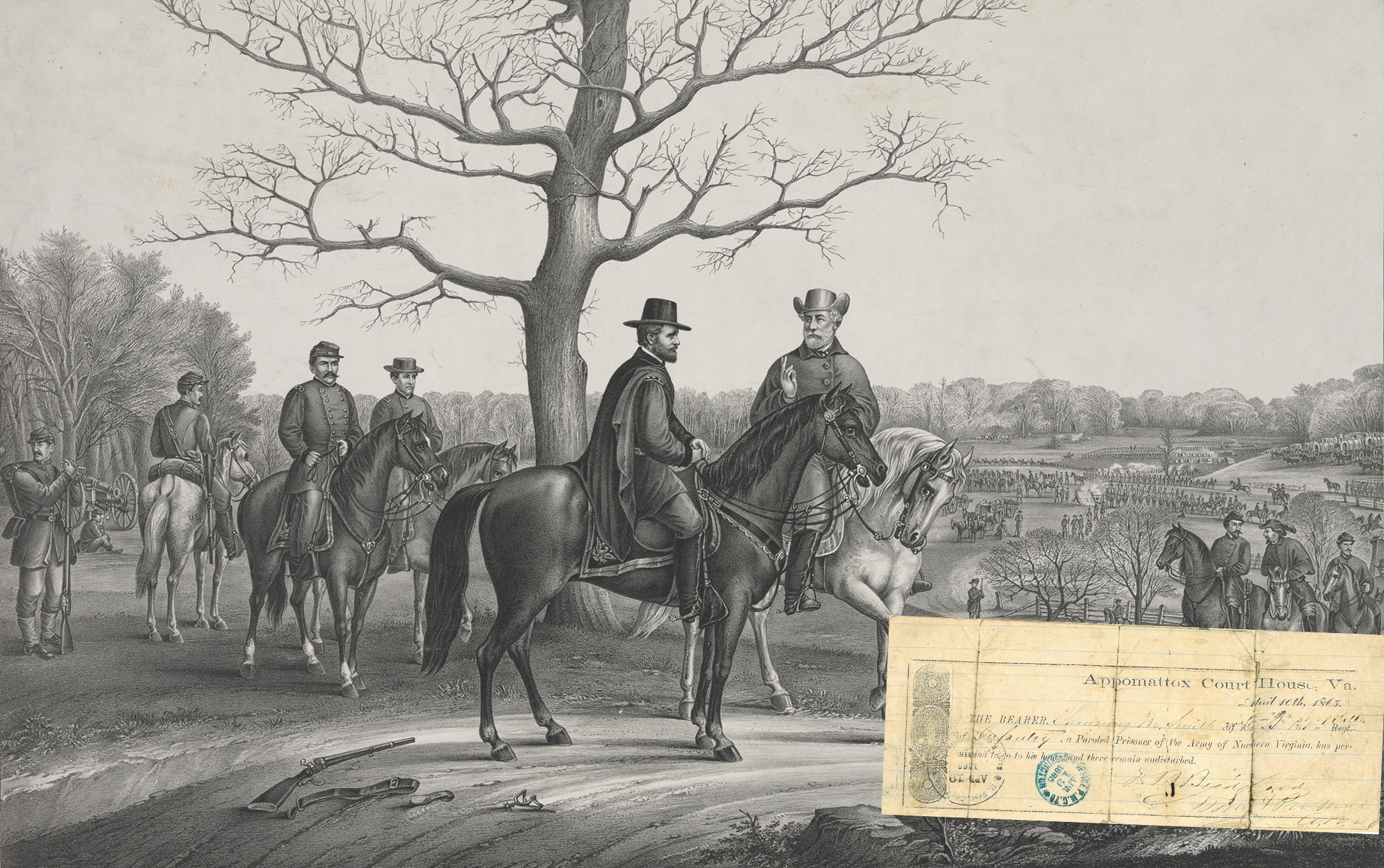

At the April 9, 1865, surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, General Ulysses S. Grant’s terms had promised that General Robert E. Lee’s men would be allowed to return to their homes immediately. But Lee and Grant had failed to discuss the specifics of this process. After his meeting with Grant on April 9, Lee began to worry about the logistics of getting his men home. Early on the morning of April 10, he drafted a letter to the Union general-in-chief asking for guidance. Before departing for Washington, D.C., that morning, Grant decided that he should meet with Lee once more. Halting on a slope just northeast of the courthouse, the two generals sat astride their horses for nearly half an hour discussing a few more details while their principal officers held back, out of earshot. Lee turned to the concerns that had plagued him the previous evening: Unlike the surrender at Vicksburg, where Confederates headed back into their own territory, his men now would be forced to move through Union lines to return home. How could he be sure that their paroles would be honored and that they would not be arrested or treated as deserters? Calling Maj. Gen. John Gibbon to them, Grant explained that Lee was “desirous that his officers and men should have on their persons some evidence that they are paroled prisoners.” Lee concurred, observing that he wanted to do all in his power to protect his men. Gibbon informed them his corps had a small printing press from which blank forms could be struck off. After the passes had been filled out and signed by their officers, they could be distributed to each officer and man within Lee’s army. Before heading toward Burkeville Junction around noon, Grant offered the surrendering Confederates one more provision. Special Field Orders No. 73 stated that “all officers and men of the Confederate service paroled at Appomattox Court House who to reach their homes, are compelled to pass through the lines of the Union armies, will be allowed to do so, and to pass free on all Government transports and military railroads.” The order was as practical as it was generous. By sending the paroled prisoners to their homes as quickly and efficiently as possible, Grant hoped the war’s end would come more swiftly. —C.E.J.