Shortly after the Army of Northern Virginia laid down its arms on April 12, 1865, thousands of Confederate veterans began heading back to their homes. Throughout the Carolinas and into Georgia and beyond, they clambered onto railroad cars. Railroad travel proved sporadic and unpredictable at best. Men might catch a freight train in Greensboro or Salisbury only to find that they must disembark where the tracks had been destroyed and hoof it to the next station. Even among those who rode the rails for a portion of the trip, a substantial amount of time was spent walking.

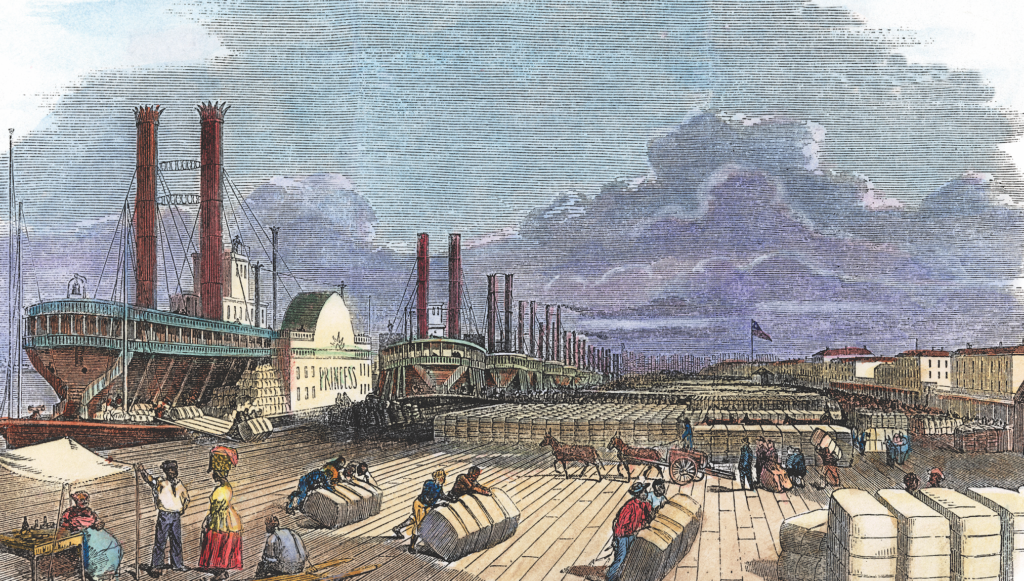

A significant number of soldiers from the Deep South had first gone to City Point and Fort Monroe, Va., hoping to sail south. After traveling by train from Burkeville to Fort Monroe, 450 parolees from several Alabama and Georgia regiments climbed aboard the Admiral Dupont. The 200-foot side-wheel steamer had begun the war as a Confederate blockade runner, but now it sailed south to Savannah filled with prisoners of war. On the evening of April 19, the men disembarked from the great iron ship before marching to the Camp of Distribution near the Central Railroad grounds to await the trains. Several days later, a guard of 22 men from the 3rd Pennsylvania Artillery accompanied more than 500 paroled rebels aboard the steamer Kingfisher into Savannah’s harbor. But this homecoming was marked by an additional sorrow. During the trip, 22-year-old Private Richard Cribb of the 10th Georgia Battalion succumbed to illness. So close to his Dooley County home, he died at sea, his comrades committing his body to a watery grave.

Keeping each other company

Although the brigades and regiments splintered more as they moved south, men continued to travel in small groups rather than alone. Sergeant Major Lewis H. Andrews of the 8th Georgia had been among the approximately 250 men of Anderson’s Brigade who had marched away from Appomattox. Yet within a few days, Andrews and five others had struck out on their own. Even with their smaller party, finding food remained almost as challenging as securing transportation. At Salisbury, Andrews and his comrades waited hours at a Union post for “eatables,” only to learn that none would be forthcoming.

They left in disgust, marching another nine miles before finding a pile of straw in which to sleep. The train that arrived the next morning proved equally packed, “on top and everywhere else,” so the men designated as foragers set out to find something— anything—to eat, but returned with only two canteens of milk. After another restless night in the straw, they began marching again before sunrise.

Scavenging for Sustenance

Recommended for you

Marching toward Charlotte, their luck improved when a civilian supplied them with a lunch of bread, butter, pie, and milk. A few days later, still ravenous, two of the men literally ate crow. When they pronounced the meal “fine,” Andrews quipped he was willing to take their word for it.

But the homeward-bound trip could prove perilous beyond the quest for food and transportation. Having made their way well into North Carolina, Gus Dean and 14 of his comrades of the 2nd South Carolina Rifles rejoiced when they stumbled upon an unoccupied shed after a long day’s march. But the good fortune proved short-lived. During a particularly heavy downpour, the shed collapsed on the sleeping men. Large logs came crashing down on William McClinton, crushing his head and chest, killing him instantly. A piece of scantling landed on Dean’s head and hip, pinning him under the debris for more than an hour before his companions managed to pull him out.

Others encountered unexpected detentions by Union forces. Lewis Andrews and his traveling companions arrived in Greensboro on April 19. But that evening, as Joe Johnston and William T. Sherman awaited approval of their proposed surrender terms, Union troops forced Andrews and his comrades into a parole camp. In a town rife with rumors—that President Lincoln had been killed, that Secretary of State William Seward had been wounded, that Jefferson Davis had been captured, and that an armistice of 10 days was in effect—the parole camp offered the safest respite for the night.

In Montgomery, Ala., the Federal provost marshal assigned members of John Bell Hood’s Texas Brigade to quarters near the city’s artesian well. For a week, the men bivouacked in the two-story building as more of the brigade drifted into the town and their commanders, Captain W.T. Hill and Major W.H. “Howdy” Martin, attempted to secure passage to Mobile. As a reminder that they were prisoners of war passing through Union lines, the provost marshal ordered the men to have their paroles countersigned before boarding a steamer bound for Mobile. Reaching New Orleans several days later, the Texans again found themselves assigned to quarters in a large cotton shed—this time under guard—while they waited more than nine days to make the next leg of their journey.

Looking for Friendly Faces

Those still on the road sought out Confederate-sympathizing civilians willing to provide food and lodging. Most were individuals or families, such as the Stileses near Asheboro, N.C., who prepared a “big mess of chicken for the crowd” of soldiers passing their home on April 21. Indicative of what had changed as much as what had not, in countless instances paroled men found themselves waited on by men and women who remained in bondage despite Lee’s surrender. Each day, soldiers filled the backyard and kitchen of Eliza Andrews’ Georgia home. To accommodate the hundreds, perhaps thousands, of men, her mother had kept two enslaved women “hard at work, cooking for them.”

In other instances, entire communities worked to assist the soldiers, such as the ladies of Augusta, Ga., who organized a food and clothing drive for soldiers passing through the city, or the town of Edgefield, S.C., which held a “grand barbecue” of mutton, shoat, hams, turkeys, chickens, cakes, and custards to show their gratitude for the “toilsome and dangerous service these brave men have rendered.” Looking more like the homecoming of a triumphant army rather than a defeated one, the “gray coats and brass buttons and tinsel braidery…and brave, manly, young hearts were in full force.”

Whether opening up their homes to small groups of men or hosting the remnants of entire brigades on their lawns, many of the civilians who aided the men on their journey home expressed a deep and continuing devotion to the Confederacy—and its soldiers.

Such sentiments allowed them to forgive some returning soldiers for their transgressions. Eliza Andrews watched as soldiers seized horses in broad daylight in a Georgia town. When one veteran caught her staring at him as he led a mule away from its owner, the soldier called out, “A man that’s going to Texas must have a mule to ride, don’t you think so, lady?” Although she offered no reply, Andrews conceded in her diary that the Texan had so far to go that the temptation for him to take another man’s mule was great.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Looting and pillaging

On May 1, in a scene reminiscent of those that had taken place at Danville, Va., and Greensboro, a mob of Confederate soldiers ransacked Augusta, looting government stores and pillaging a tobacco shop. Yet the city paper tried to rationalize their actions. Using the same logic as that applied by Confederate officers who believed the men were due government goods as compensation for their service, the paper observed that “the sacking of government stores would have been proper enough had there been anything like fairness in the plunder of the property.” Instead, it proved “an unequal distribution…and the parties engaged have done great injury to their fellow soldiers who have not yet arrived.”

The paper declared the pillage of the tobacco shop “the most heinous part of the affair” because it affected private individuals. But, the editors insisted, “we do not believe that many of those implicated were of Lee’s or Johnston’s armies, if so, they were instigated by shameless parties.”

Should The Looters Have Been Forgiven?

Echoing Lee’s farewell address at Appomattox in which he had praised the loyalty, valor, and “unsurpassed courage and fortitude” of “the brave survivors of so many hard-fought battles,” newspapers and civilians alike reasoned that Confederate soldiers had fought valiantly and bravely only to be overwhelmed by superior Northern resources. Of course, they should not engage in looting and plundering. But many Confederate sympathizers believed it could be forgiven as part of the social contract that implied soldiers, especially those who had given their all, were entitled to be fed.

Although the vast majority of the White Southern population had supported the Confederate war effort, as the Army of Northern Virginia dispersed across the countryside, soldiers encountered both devoted Unionists and folks who had grown weary of Confederate impressment agents and refused to give any more for a cause that was certainly lost. Near Thomasville, N.C., a soaked and exhausted John Dooley and his comrades could find no place to dry their clothes or no morsel to eat. “The people in this vicinity seem rather unfavorable towards Confederate soldiers and are very distant and inhospitable,” he complained. “Most of them are of that persuasion call[ed] ‘Dunkers’ or ‘Friends’ who find their religion very convenient when war arises.”

Harry Townsend and his small band of Richmond Howitzers were warned to be careful upon crossing the border from Virginia into Stokes County, N.C. “The people are Tories or Union men in sentiment and are much greater lovers of the Yankees than of the Confederates,” Townsend observed. “They often attack Confederate soldiers who may be passing through this country and strip them of their valuables.” But the Unionist threat failed to materialize.

Starving and Naked

In the pro-Union mountains of eastern Tennessee, Captain William Harder and his large group of paroled men were not so fortunate. Arriving in Sullivan County on April 23, the men were in desperate straits, “all nearly starved…naked and befuddled.” The locals refused to feed the Confederates, but they did offer a warning. “We were told that every Confederate that went through or attempted to go through eastern Tennessee were killed and that we would meet the same fate,” Harder explained. Still, the men pressed on to Greeneville, the home of President Andrew Johnson. With the U.S. troops either unwilling or unable to provide rations, the paroled men traded Confederate scrip to Federals for crackers and meat.

Yet even in regions sympathetic to the Confederacy, the refusal or inability of civilians to provide food led some soldiers to resort to violence and plundering—just as Union and Confederate authorities had feared. Lieutenant David Champion, a Georgian, and his traveling companions became outraged when an older man in the Carolinas refused to accept Confederate money for corn and bacon. “Seeing it was useless to try to trade with him,” Champion explained, “I ordered the boys to go to his corn crib and smoke-house and get the corn and bacon we needed. We carried the corn to a mill nearby on the creek and ground it and borrowed his washpot to cook the meat in.” Not only did they take enough to satiate themselves in the moment, but they filled their haversacks before departing.

When Lee’s men reached Charlotte—as in Danville and Greensboro—a mob of Confederate soldiers raided Confederate warehouses. Frank Mixson and Jim Diamond, who had already enjoyed their share of loot in Danville, encountered a large crowd of Lee’s paroled men taking whatever they could shove into their pockets and makeshift haversacks. “But as we had plenty to eat we didn’t take much hand in it,” Mixson maintained. The two did, however, abscond with “a bolt of real good jeans.”

From President to refugee

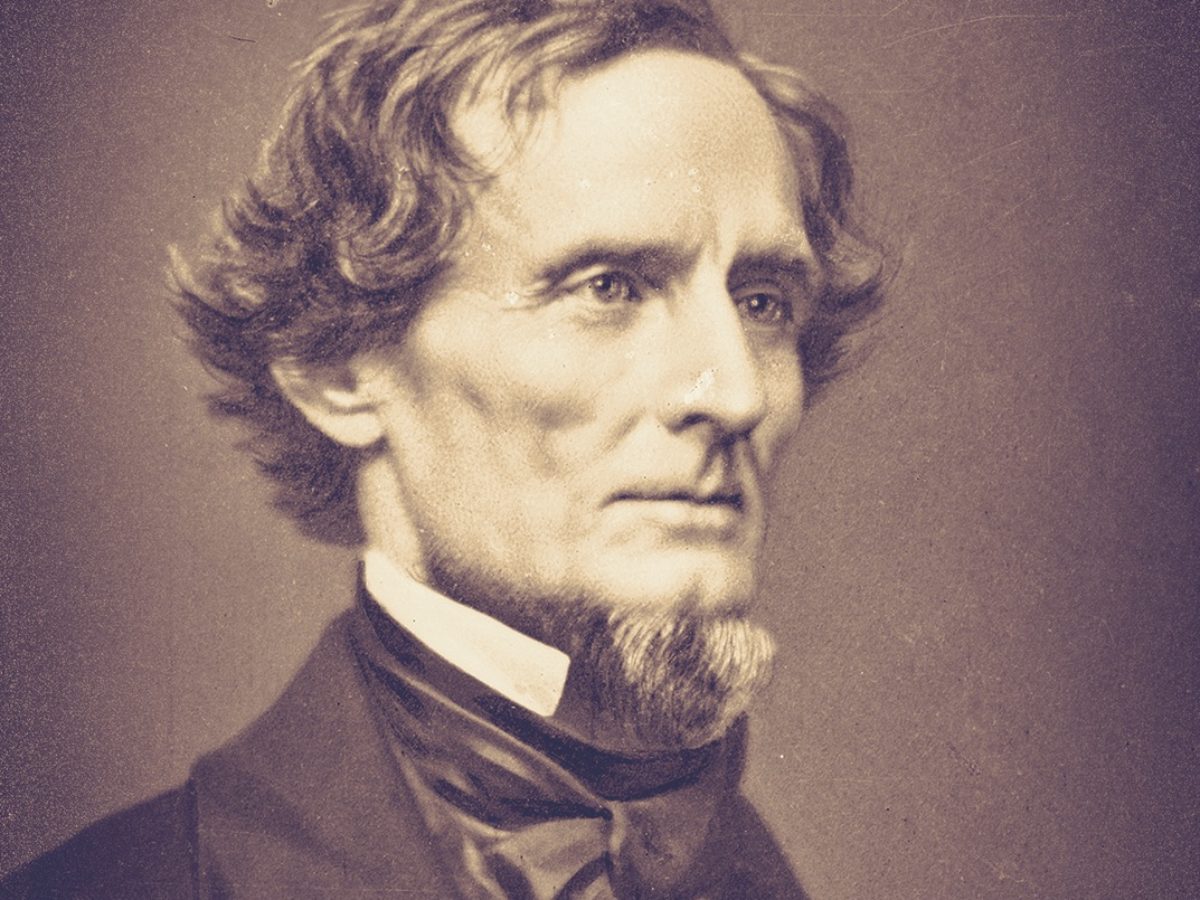

As Charlotte erupted in chaos, John Dooley, a paroled prisoner from Johnson’s Island who had headed south along with many of Lee’s men vowing to continue the fight, now contemplated his options. Charlotte was rapidly filling with stragglers, officers, and government officials, including Jefferson Davis and his Cabinet, all of whom remained determined to push into the Trans-Mississippi. Each hour, hundreds more arrived along the railroad from Salisbury. But with no resources and no place to stay, should Dooley return to Virginia?

While he waited, others continued on their southward journeys into South Carolina. Crossing the border to the west of Charlotte, a surgeon of the 16th Georgia and his small mounted party found themselves in Union-controlled territory where their parole passes proved useful. At the Catawba River, they met troopers from the 12th Ohio Cavalry who escorted them through the lines before stopping in Yorkville (present-day York), where they again showed their passes to obtain U.S. rations. If the Yankees proved willing to assist the paroled Confederates, locals did not. Close to the Georgia border, the surgeon complained that the South Carolinians had proved especially inhospitable, refusing them at all but two houses along the way. “Would to compare S.C. with either N.C. or Virginia t’would be odious,” he scribbled in his diary. “There is no comparison both states being so far ahead of ‘little’ S.C. in generosity and hospitality.”

Finally Coming Home

As they continued their trek, in scenes repeated from Virginia to Texas and every place in between, Lee’s men began to reach their homes. The first priority for many of these soldiers hoping to resume their civilian lives was a bath or even a haircut. For men who had endured filth a good portion of their soldiering careers, cleaning themselves up offered one more step in the process of becoming a civilian.

After walking more than 200 miles, on April 20 Robert Crumpler and his comrades from the 30th North Carolina halted to wash and shave in the hopes of making themselves “as presentable as possible” before venturing on to their Sampson County homes. Others had been unable to wash their clothing, shave, or bathe before arriving home and therefore divested themselves of their filthy, tattered uniforms and cleaned themselves as quickly upon arrival as they could. Surgeon Spencer Welch of the 13th South Carolina had spooned with four of his companions each night and ridden astride his small mule for more than three weeks.

Upon reaching his father’s home in Newberry, Welch shed his dirty, vermin-infested rags for “clean, whole clothes” and crawled into a real bed. These simple acts did more than anything to restore him. “I feel greatly refreshed,” he wrote his wife. And though the teenage Frank Mixson was overjoyed to see his loved ones, his arrival home prompted an immediate trip to the outhouse, where his family instructed him to wash and change into fresh clothing. His tattered and reeking Confederate uniform, however, was to be buried.

A New World

Whether settled back at their homes or still on the road, Confederates moving across the South after Appomattox witnessed a world far removed from the slaveholding society they had pledged to defend in 1861. So did African Americans. On farms and plantations, cities and towns, enslaved men and women bore witness to the change the war had wrought. “I seen our ’Federates go off laughin’ an’ gay,” remembered an ex-slave from Alabama. They had departed for war singing “Dixie,” certain they were going to win, but now they returned skin and bones, their eyes hollow and their clothes ragged.

At least some enslaved men who had been attached to Lee’s army returned alongside their former masters, anxious to be reunited with their own free families. Edwin Bogan of North Carolina was one such man who traveled home along with his former owner to his wife and young son. But newly freed men and women also joined the Rebel soldiers on the roads crisscrossing the region, underscoring all that had been done and undone during four years of war.

Nowhere was the new order more apparent than in Confederate soldiers’ encounters with U.S. Colored Troops. On April 26, the Wilmington steamed into the Savannah port with 690 paroled Rebels, including David L. Geer and other members of Finegan’s Florida Brigade, who claimed to have killed two USCT soldiers back in Virginia.

In Georgia, their deadly retaliation continued. While awaiting a ship to Jacksonville, a Black sentinel had reportedly stomped out the Floridians’ campfire. Enraged, they plotted his execution: Using a surgeon’s knife, they slashed the Black soldier’s throat, then tossed him and all evidence of the crime in the river. When White officers grew suspicious about the missing sentinel and threatened to send the Confederates to prison on the Dry Tortugas, Geer and 63 other Florida soldiers still awaiting steamers fled in the middle of the night, traveling overland rather than risk further inquiries. For a third time since leaving Appomattox, they had killed Black soldiers—and gotten away with it.

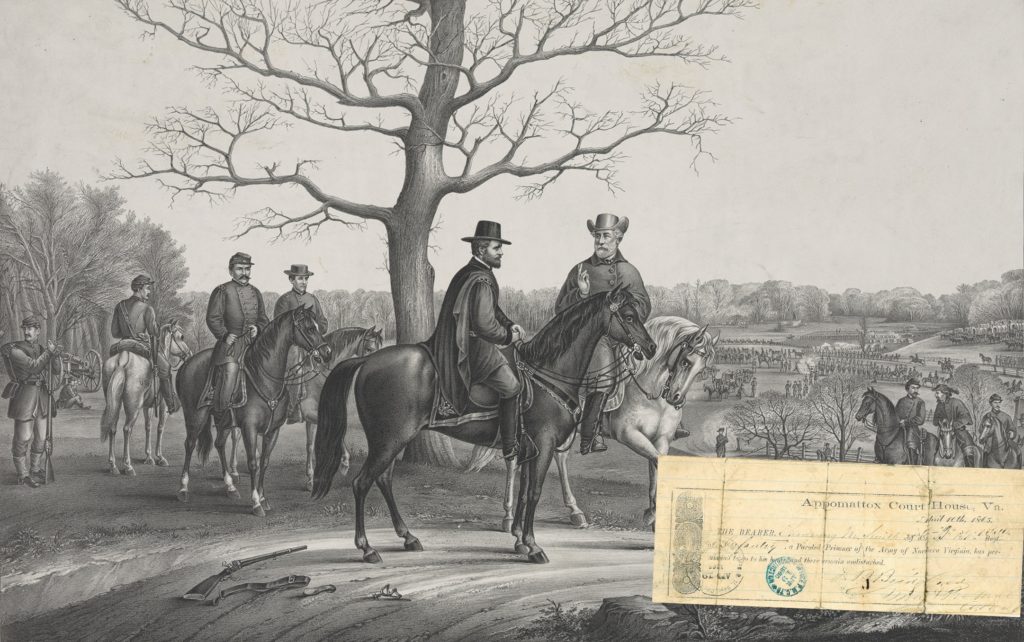

At the April 9, 1865, surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, General Ulysses S. Grant’s terms had promised that General Robert E. Lee’s men would be allowed to return to their homes immediately. But Lee and Grant had failed to discuss the specifics of this process. After his meeting with Grant on April 9, Lee began to worry about the logistics of getting his men home. Early on the morning of April 10, he drafted a letter to the Union general-in-chief asking for guidance. Before departing for Washington, D.C., that morning, Grant decided that he should meet with Lee once more. Halting on a slope just northeast of the courthouse, the two generals sat astride their horses for nearly half an hour discussing a few more details while their principal officers held back, out of earshot. Lee turned to the concerns that had plagued him the previous evening: Unlike the surrender at Vicksburg, where Confederates headed back into their own territory, his men now would be forced to move through Union lines to return home. How could he be sure that their paroles would be honored and that they would not be arrested or treated as deserters? Calling Maj. Gen. John Gibbon to them, Grant explained that Lee was “desirous that his officers and men should have on their persons some evidence that they are paroled prisoners.” Lee concurred, observing that he wanted to do all in his power to protect his men. Gibbon informed them his corps had a small printing press from which blank forms could be struck off. After the passes had been filled out and signed by their officers, they could be distributed to each officer and man within Lee’s army. Before heading toward Burkeville Junction around noon, Grant offered the surrendering Confederates one more provision. Special Field Orders No. 73 stated that “all officers and men of the Confederate service paroled at Appomattox Court House who to reach their homes, are compelled to pass through the lines of the Union armies, will be allowed to do so, and to pass free on all Government transports and military railroads.” The order was as practical as it was generous. By sending the paroled prisoners to their homes as quickly and efficiently as possible, Grant hoped the war’s end would come more swiftly. —C.E.J.

Upending the old Social Order

Other interactions with Black soldiers proved less deadly but no less revealing of how much the social order had changed. At Selma, Ala., U.S. officers ordered members of Hood’s Texas Brigade to disembark from a train so that a USCT regiment might travel to Mobile. “We protested, of course, and bitterly, against what some of our men denounced as a regular ‘Yankee trick,’” wrote Captain W.T. Hill of the 5th Texas, “but our protest was unheeded, and we had to wait at Selma until the next day.”

Several days later at New Orleans, the Texans found themselves guarded by a USCT company—a slight that Hill believed to be intentionally demeaning. The presence of Black men in uniforms, perhaps more than the surrender itself, represented the death of the Confederacy and a new racial order.

Yet some Confederates remained unwilling to acquiesce to such a reality. From Greensboro on April 25, Gordon McCabe wrote his future wife, Jane. He had arrived in the city on the 17th, and since then had received no word from Virginia. “Everybody here asked eagerly, ‘What is Virginia going to do?’” Fight, he told them. A handful of young Virginians had made their way to the railroad town hoping to join Joe Johnston’s forces. Both Ham Chamberlayne and David McIntosh had continued southward toward South Carolina, he told her. But others remained in North Carolina weighing their options. “There are a great many Va. officers here, who are forming themselves into a Battalion—a sort of Corps d’Elite,” he explained. “Where we are going, of course, I do not know; to Trans-Miss., I suppose, if we can elude Sherman.” But a thread of realism ran through him. “If God spares my life, and this Army should be surrendered,” he continued, “I propose to return to Virginia before going abroad, unless France and the United States get to fighting, when we may probably get something to do in the service of H.S.H. Napoleon III.” He would go to Mexico and fight for the French. But he would not—could not—live under Yankee rule.

Little News

During the last week of April, Harry Townsend and his fellow artillerists finally reached their destination of Lincolnton, N.C. Perched on a high bluff above the South Fork of the Catawba River, the town had been the rallying point for those who had escaped Appomattox and hoped to continue the struggle. Here they found residents handing out provisions at the courthouse for both paroled and unparoled soldiers as well as offering beds in several local hotels and residences. But they found very little news. “We had expected to gain some definite information at this point which could guide our future course, but found no orders awaiting us, nor any officer in command,” Townsend recorded in his diary. Instead, they spoke with a paroled lieutenant who informed them that Secretary of War John Breckinridge had refused the service of officers and men from Lee’s army and had bid them to return to their homes, as no Confederate government now existed east of the Mississippi River. Sympathetic to their aims, however, the lieutenant advised them to go to Charlotte, where they might learn something more definitive. Townsend and his comrades headed for the Queen City.

For McCabe, Pendleton, Townsend, and others who remained committed to the cause, the Army of Northern Virginia had not yet been thoroughly vanquished. For Confederates determined to return home to loyal Union states, the story would prove much different.

Caroline E. Janney is the John L. Nau III professor in the History of the American Civil War and Director of the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History at the University of Virginia.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.