In the humiliating aftermath of the Civil War many dispirited Southerners rallied around Cullen Baker, a cold-blooded Arkansas killer they propped up as a defiant ex-Rebel who continued to champion the Lost Cause against detested Union occupation troops and Freedmen’s Bureau agents. Some of his fellow former Confederates sheltered, fed and supplied the fugitive, helping him elude pursuing soldiers and posses.

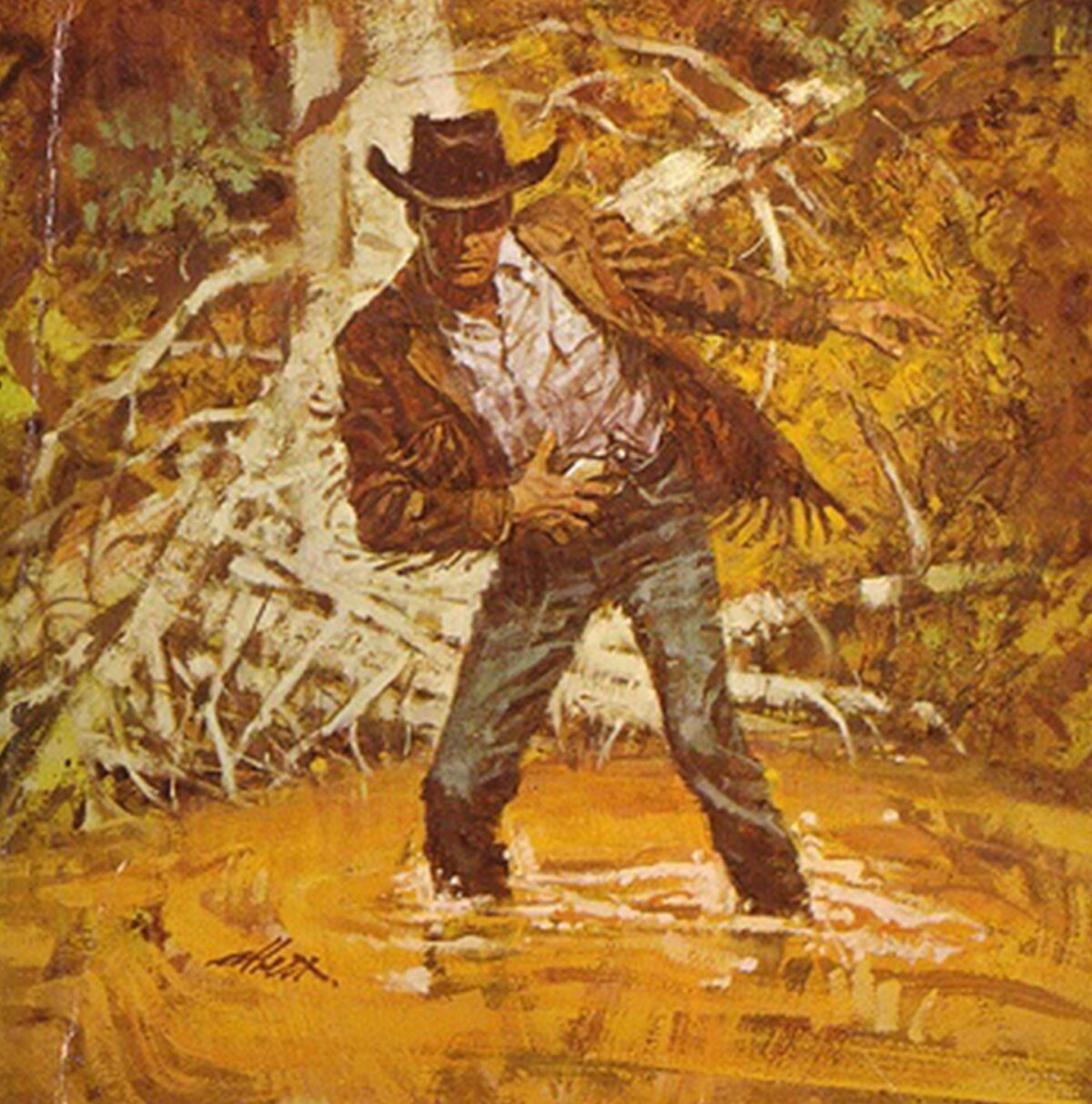

But Baker’s long string of killings—into the double digits—actually began well before the war. The killer’s bloody tally prompted Western writer Louis L’Amour to loosely—albeit very loosely—base his 1959 novel The First Fast Draw on Baker.

In fact a shotgun was Cullen Baker’s preferred weapon, and many of his killings were outright murders of unarmed or unsuspecting victims. Baker killed his first man when he was 19. In the midst of the Civil War he deserted the Confederate army to become a wanton guerrilla raider. He was clearly mentally disturbed, and his continual drinking deepened his psychosis. Yet despite his reputation as a vicious, homicidal, alcoholic deserter, Baker somehow managed to glean sympathy and even a measure of respect during an era of frontier gunplay.

Born in 1835 in west Tennessee’s Weakley County, Cullen Montgomery Baker moved with his family to Texas when he was four, and they eventually settled on a farm in Cass County. The hot-tempered youth enjoyed hunting and became a crack shot but was prone to misbehavior, fistfights and heavy drinking.

In January 1854, when he was 18, Baker married Mary Jane Petty, but marriage didn’t improve his disposition or stem his drinking habit. That fall, in a drunken rage, he bullwhipped an orphan boy. When middle-aged neighbor Wesley Baily came forward as a witness, Baker promptly shot him in front of his family and then fled to Arkansas.

After his wife fell ill and died in 1860, Baker left their little girl with in-laws and largely forgot her. With the onset of the war the following spring, he returned to Texas and joined a Confederate cavalry company out of Jefferson. He soon deserted that unit and in February 1862 enlisted in another cavalry company at Linden, north of Jefferson.

In the midst of his checkered Confederate service, Private Baker married 15-year-old Martha Foster of Cass County and went AWOL to be with her, before wangling a “disability discharge” in 1863. Baker soon headed up a band of fellow criminal misfits that hid out in the southwest Arkansas bottomlands and swamps of the Sulphur River. Rumors had it the “Swamp Fox of the Sulphur” killed three or four Union troopers and a number of slaves.

A year after the war Baker’s young wife died. Increasingly unbalanced and dissipated, he erected an effigy clad in her clothing. Within two months he proposed to his late wife’s 16-year-old sister, Belle. The girl and her parents stiffly declined. Belle instead married schoolteacher Thomas Orr. Predictably, Baker began to bully Orr, who had a deformed hand. After Baker tried to hang the teacher, Orr rallied fellow citizens against the outlaw.

Baker resumed his deadly depredations in northeast Texas, southwest Arkansas and northwest Louisiana, leading his gang in raids that inevitably ended in robbery and murder. In Queen City, Texas, storekeeper John Rowden confronted the outlaw, and Baker triggered a load of buckshot into his chest.

After his cold-blooded killing of a Texas freedman on his own farm, Baker faced determined pursuit by William Kirkman, an agent for the Freedmen’s Bureau, which Congress had established in 1865 to help freed blacks during Reconstruction. On June 25, 1867, Kirkman and several soldiers caught up with Baker in Boston, Texas. In the ensuing wild street shootout Baker killed Private Albert Titus with a shotgun blast, but Kirkman winged the outlaw leader in the arm. Elusive as ever, the wounded Baker managed to escape.

Their game of cat and mouse continued more than a year, but in the early morning hours of Oct. 7, 1868, Baker cornered Kirkman in his Boston office and, with three accomplices, opened fire. Riddled with 16 shotgun and pistol balls, Kirkman triggered one shot before falling dead. Baker next went to southwest Arkansas to get bureau superintendent Hiram Willis, who had issued scathing public condemnations of the outlaw leader. On October 24, Baker and a half-dozen gang members confronted Willis in a buggy on a business call, accompanied by a driver, an area planter and the local sheriff. When Willis went for his gun, the outlaws killed him, the driver and the planter. The sheriff bolted.

Six days later, Baker and other outlaws murdered two more freedmen. When freedman Jerry Sheffield publicly boasted he would lead pursuers to their hideout for a small reward, Baker and accomplices shot him down outside Queen City on December 6.

Baker and men eluded the soldiers and citizens’ posses by crossing state borders and slipping into the Sulphur River swamps. But posted rewards assured relentless pursuit, and schoolteacher Orr led the posse that ultimately caught up to the gang. On Jan. 6, 1869, just east of Queen City across the Texas line in Arkansas, the pursuers surprised Baker and a cohort as they ate lunch. One account claims an accomplice had laced their food and liquor with strychnine, though to be certain, posse members fired bullets into Baker and his henchman.

Possemen found a shotgun, four revolvers, three derringers and six knives on Baker’s corpse. Orr took the two bodies to military authorities in Jefferson. Baker’s grave in that city’s Oakland Cemetery bears a Confederate military marker, but the killer had brought no honor to the defeated South.

This story was published in the October 2016 issue of Wild West. For more stories, subscribe here.