In May 1862, UNION TROOPS from New York—or any state represented in the Army of the Potomac, for that matter—would not have welcomed running into anything associated with Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. But when friends of mine from western New York, heading south on Interstate 95 for vacation, came upon a brown road sign in central Virginia referencing the Confederate general, they were delighted.

“We saw the sign for the Stonewall Jackson Shrine and thought of you,” they texted me, knowing my affinity for the legendary Army of Northern Virginia commander. This particular sign near I-95’s Thornburg, Va., exit—since renamed the Stonewall Jackson Death Site—had caught their eyes, just as it does for thousands of battlefield tourists every year.

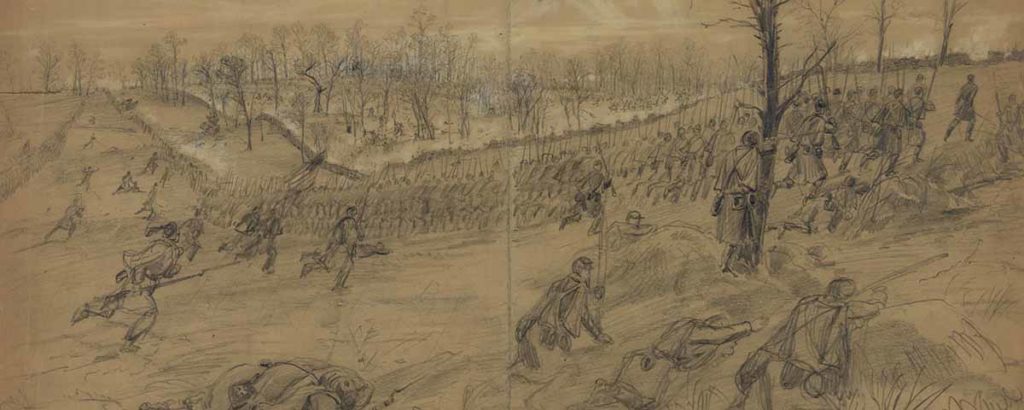

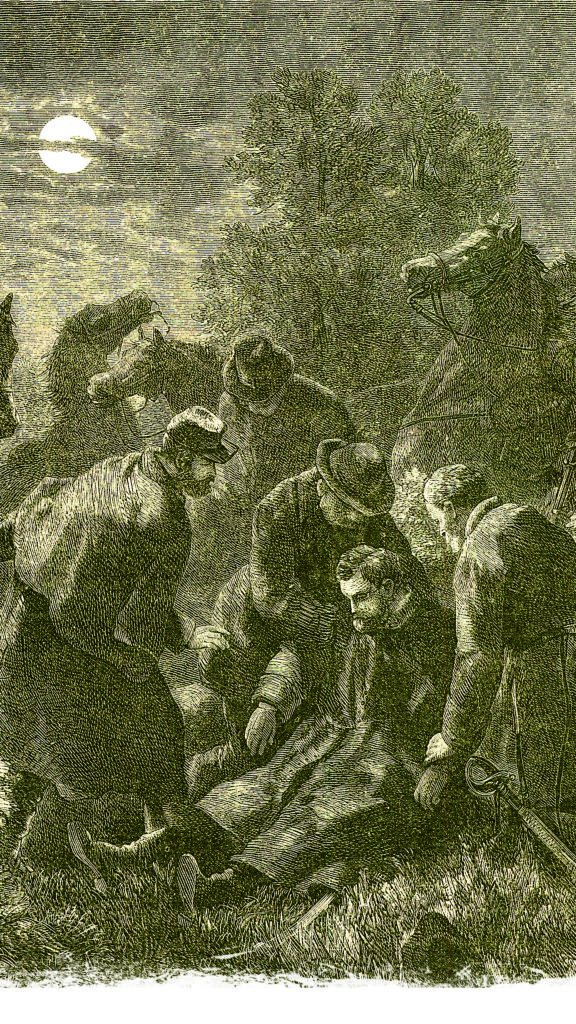

Stonewall Jackson, of course, was mortally wounded on May 2, 1863, at the height of his great triumph at the Battle of Chancellorsville. That afternoon, Jackson’s Corps had rolled up Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard’s 11th Corps on the Army of the Potomac’s right during a daring flank attack still studied by military theorists. The assault crippled Union Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker’s offensive. But Jackson wanted more. As evening began to fall, the general impatiently conducted a reconnaissance in the thick woods in front of his lines, eager to discover the Union positions and perhaps continue his attack. A rippling volley from troops in one of his own North Carolina brigades, however, knocked Jackson from his horse.

Jackson endured amputation of his left arm and a jarring 27-mile ambulance ride the next day to Thomas C. Chandler’s “Fairview” Plantation near Guinea Station, site of the shrine that caught my friend’s attention. He remained at one of the plantation’s outbuildings until he died of pneumonia on May 10. ¶ In the scenario related above, Jackson, the once-feared commander of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Second Corps, has essentially been reduced these days to a roadside attraction. In the area around Chancellorsville, in particular—the site of Jackson’s accidental mortal wounding—the memory and memorialization of Jackson has been carefully shaped to bring in tourist dollars. While that might seem an ignoble fate for one of the best-known generals in American military history, it’s a tradition that dates back more than 140 years and was started by members of Jackson’s innermost circle.

ENTER JAMES POWER SMITH

James Power Smith had been a divinity student at Hampden-Sydney College prior to the Civil War. Assigned to Jackson’s staff in the fall of 1862 during the Maryland Campaign, Smith served as aide-de-camp. Their common Presbyterianism and devout natures helped to form a close bond between them.

After the war, Smith completed his studies and, following his ordination, returned to the Fredericksburg area to serve as the minister at the local Presbyterian church. He also married the daughter of one of the city’s most prominent residents, James Horace Lacy, owner of the stately mansion Chatham on the banks of the Rappahannock River and the Ellwood country estate in the middle of the Wilderness.

Recommended for you

The Lacy family cemetery was also at Ellwood, and it was in that cemetery that Stonewall Jackson’s arm was buried. In one of those odd little coincidences, James Horace’s brother, the Rev. Beverly Tucker Lacy, served as Jackson’s chaplain. After Jackson was accidentally shot, an ambulance took him to a field hospital in the rear near the Wilderness Tavern, where surgeons removed his wounded left arm. The Rev. Lacy, determined to give the limb a proper Christian burial, wrapped it in a sheet and carried it across the fields to his brother’s nearby plantation. Jackson’s “shattered arm was buried in the family burying-ground of the Ellwood place…near his last battlefield,” Smith later recounted.

Thus bound together by events and family connections, Smith and the Lacy brothers found themselves years later riding across the Chancellorsville battlefield along the Orange Plank Road. Recounting the battle, they decided the location of Jackson’s wounding should somehow be marked.

Recent improvements to the road had unearthed a large quartz boulder at the nearby Luckett Farm (some accounts place it on Lacy’s Ellwood property). Enlisting the help of several neighbors, they “brought men and a logging truck from Ellwood and placed the quartz boulder marking the place of Jackson’s wounding.”

It’s worth noting Smith referred to “the place” of Jackson’s wounding, not “the spot.” The crew planted the rock in a prominent location that would let passers-by clearly see it. Thus, the stone did not mark the exact location. At 3-feet-4-inches tall and weighing about three tons, the boulder was supposed to eventually have a plaque or inscription added, but explanatory text never materialized.

DATING THE ROCK

In 1983, while compiling a study of the battlefield’s monuments, Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park (FSNMP) staff historian Don Pfanz realized no one knew just exactly when the team had placed “Jackson Rock.” Pfanz dated the stone back “at least as far as 1883 and may have been in place prior to 1876.” In 2012, FSNMP Chief Historian/Chief of Interpretation John Hennessy uncovered a newspaper article that described “a large boulder of white quartz rock, from near the Wilderness.” The article fixed the date of the project as September 27, 1879. “Mystery solved,” Hennessy said on the park’s blog, Mysteries & Conundrums.

Hennessy also shared an account from an Ohio traveler visiting the battlefield in 1881. “Moving in the midst of timber for somewhere near a half mile [from the Chancellor house site] we come [to] a big stone planted steadfastly by the roadside” the Buckeye wrote. “I learned that this was the spot where the bleeding warrior fell from his horse…. The stone is a rough block of white flint, quarried here in the Wilderness….The silent woods are around. The stone is as still as though the bones of a man of fame were beneath.”

But even here in the Wilderness, he said, “romance may be spoiled.” Near the rock, the traveler noted something that modern motorists, too, find all too common: the 1881 equivalent of a billboard. “Nailed against the red oak,” he reported, “is a broad board with the sign:

Willis & Grasty,

Sewing Machine Agents

Dry Goods, Shoes and Hats,

Cheap for Cash

“Thus within hand’s reach of Stonewall’s stone,” the traveler wrote, “trade leaves its mark and enterprising dealers reap profit from the glances of the reverential passers-by.”

formal memory

In 1887—eight years after the placement of the Jackson Rock—local residents launched an effort to erect a more formal monument to Jackson. Again, Smith would be heavily involved, although Union Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick gets the credit for kicking things off.

Sedgwick had been killed by a sharpshooter’s bullet on May 9, 1864, during the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. In May 1888, Union veterans planned to gather on the battlefield to dedicate a monument to the fallen “Uncle John.” News about the preparations for that ceremony circulated throughout the Fredericksburg area in the months leading up to the event. Jackson partisans realized that if Sedgwick was going to have a monument, Jackson should have one, too.

“What hearts these northern men have that they come all the way down here to do this for their general!” cried a local Confederate veteran attending the dedication of the Sedgwick monument, John Lewis. “I honor them for this. What hearts they have!”

Described by one witness as being fortified with “a trifle more whisky in him than was really necessary,” Lewis loudly lauded the way the Northern veterans remembered their dead general. “How they stand by their hero!” he continued. “How they remember him! How they care for his glory! But we—yes, we have given up Jackson.” In his boisterous lament, he said, “[I]t makes my heart bleed that we have given up Jackson.”

By the end of the day, Union veterans—amused, annoyed, or guilted by Lewis’ lamentations—collected $50 toward the Stonewall Jackson monument.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Fundraising on the monument was well on its way by that point, with a goal of $4,000. Leading the effort was Fredericksburg Star publisher Rufus Merchant, a veteran of Cobb’s Georgia Legion, who organized what became known as the Chancellorsville Stonewall Monument Association. Merchant was elected president, and James Power Smith became its chairman. Together, they mobilized Confederate veterans and Jackson admirers across the country to contribute.

Smith chose the location for the monument, a 1.5-acre plot owned by William N. Wyeth adjacent to the location of the Jackson Rock. “When we were selecting a location,” Smith explained years later, “…the present site was selected, as being on the road—somewhat elevated—and as being a fair compromise between the two views as to the location. It is only a few rods from the exact spot wherever that was.”

Smith came to the battlefield shortly after Jackson’s wounding and admitted he didn’t know the exact spot except that it was “a few rods…farther to [the east] than where the stone and the monument now stand.”

Unable to pinpoint the spot of the wounding, Smith positioned the monument not for the sake of historical accuracy but for the benefit of travelers on the Orange Plank Road, so they could clearly see it as they passed. Nevertheless, an inscription on the side of the monument makes the inaccurate claim: “On this spot fell mortally wounded Thomas J. Jackson, Lt. Gen. C.S.A.”

Smith oversaw construction of the monument on June 5, 1888. The crew assembled a rectangular tower of 19 granite blocks, 14 feet tall (five feet taller than the Sedgwick monument that inspired it). Before they began, Smith placed his hand on the cornerstone. “I lay this corner stone to the memory of one of the best and purest men that I have known; one of my best and dearest friends,” the preacher said. “He was great, and had many qualities of the soldier and the general, but was greatest because he was good, and ‘feared God and kept His commandments.’”

Writing about the event in “Dedication of the Stonewall Jackson Monument at Chancellorsville,” FSNMP historian Eric Mink said 5,000 people turned out for the dedication ceremony on June 13, 1888, including Governor Fitzhugh Lee; former Maj. Gen. Raleigh Colston, who led one of Jackson’s divisions at Chancellorsville; Jedediah Hotchkiss, Jackson’s mapmaker; and Smith. Travelers flooded in at such numbers, the Fredericksburg Star reported, that it reminded veterans of the “vast wagon and ambulance trains that 25 years before blocked the same roads.”

park place

After the National Park Service took possession of the property in 1928, it enhanced the area with a 2-acre “Jackson Memorial Wild Flower Preserve,” complete with 175 varieties of native flowers and blooming shrubs. A trail threaded through “the deep woodlands of the area…leading along the old trenches,” a park brochure boasted. Aside from an “excellent instruction in botany,” the site also offered picnic tables and stone fireplaces.

“While the fundamental purpose of the park is historical education,” the brochure said, “its program is by no means confined to this limitation. It offers important recreational and educational features aside from critical military history.” Superintendent Branch Spaulding considered the flowers “silent witnesses” to the “unintentional blow which felled a mighty warrior.”

While the memorial preserve didn’t last, the NPS installed a more permanent feature in the area in 1963: the Chancellorsville Battlefield Visi-tor Center. “[F]rom the point of view of…strong visitor interest, the visitor center should stand near the Jackson wounding site,” argued park historian Ralph Happel, calling it “the plum in the pie thereabout, the dramatic point which people want to see and walk around.”

The visitor center’s placement fell in line with the overall approach of the NPS’s “Mission 66,” a Centennial-era initiative that constructed new visitor centers on battlefields as close as possible to the key points of action. Thenceforth, all visitors to the battlefield would converge on the site of Jackson’s mortal wounding and the memorials raised there in his honor.

smith’s further labors

The dedication of the monument did not end Smith’s role in Jackson’s roadside memorialization. In August 1903, the chaplain oversaw the placement of 10 granite markers at various locations on the area’s four major battlefields, at a cost of $250. “The purpose was not to mark battlefields, or lines of battle,” Smith later explained, “but certain points or localities that would be of lasting historic interest….” Not coincidentally, all 10 markers are related to the Army of Northern Virginia and, more specifically, Robert E. Lee or Stonewall Jackson.

One Jackson marker, “Jackson on the Field,” marks his location on Prospect Hill during the Battle of Fredericksburg on December 13, 1862. “Bivouac, Lee and Jackson” sits at the intersection of Furnace Road and Old Plank Road at Chancellorsville, marking the site of the generals’ last meeting. “Arm of Stonewall Jackson” sits in the Lacy family cemetery at Ellwood. “Stonewall Jackson Died, May 9-10, 1863” sits outside the Thomas Chandler plantation outbuilding where Jackson died. With the exception of the monument for Jackson’s arm, Smith placed all of the markers for the convenient viewing of passers-by.

The Bivouac Site held particular prominence because of Everett Julio’s 1869 painting The Last Meeting, a highly allegorical rendering of Lee’s and Jackson’s final conversation, which took place at the crossroads. The Smith marker faces the intersection so cars traveling on both roads can see it. In 1937, NPS personnel planted a pair of cedar trees at the site that, according to an in-ground bronze plaque, to “commemorate the last conference of Lee and Jackson.”

In the mid-1950s, when the park developed its first driving tour, it designed iconic seals that appeared on roadside signs for each of its four battlefields. The Chancellorsville seal depicted Lee and Jackson at the Bivouac Site. Literally, nothing said “Chancellorsville” for motorists quite like Lee and Jackson sitting together on a pair of cracker boxes in front of a campfire, reading a map. The seals eventually appeared on park merchandise, too.

The Smith marker for Jackson’s arm sits in the Lacy family cemetery far from the road, but still shows up every few years in “Roadside America”-style feature stories, blogs, and travel pieces (including an April 2013 article in Civil War Times).

At the site of Jackson’s death, the Smith marker there has hopscotched across the property over the years. Jackson died in a small white office building on the Chandler plantation at Guinea Station, next to what was, in May 1863, the Confederate railhead. Smith originally placed the marker next to the rail line so passengers traveling the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac (RF&P) Railroad could see the marker as they chugged past the site. Today, the marker sits next to the parking area at the top of the driveway to better preserve the pristine nature of the property.

in peace a glorious asset

In 1909, William White, president of the RF&P, purchased the office building and surrounding five acres. A former Virginia Military Institute cadet who fought at New Market, Va., in May 1864, White wanted to preserve the location where Jackson died because of the general’s service on the VMI faculty. He also wanted to use the site as a point of curiosity for train passengers. White promoted the site in the RF&P’s literature, and on the hillside facing the train tracks, he ordered the construction of a white rock garden with boxwood plants that spelled out the legend, “In this house, Stonewall Jackson died May 10, 1863.”

By 1926, a ladies memorial organization began an extensive rehabilitation project at the site. “[A] group of interested women transformed the bare, little room in which he ‘crossed over the river’ into some semblance of its original setting,” reported the Richmond Times-Dispatch. The article mentioned “that first pilgrimage to the Jackson Shrine”—and the name “Jackson Shrine” stuck.

In 1937, the National Park Service took over the site. In the late 1970s, it changed the name of the site from “Jackson Shrine” to “Stonewall Jackson Shrine” to prevent confusion with Andrew Jackson, Reggie Jackson, and the Jackson Five. “The notion that athletic figures or pop culture icons would be confused for the ‘real’ Jackson had been unthinkable,” wrote historian A. Wilson Greene in the foreword of Whatever You Resolve to Be: Essays on Stonewall Jackson. Greene, who had worked at the site admitted that “more families than would be palatable to quantify expressed disappointment that they had driven so far out of their way to see a house that had nothing to do with either Reggie Jackson or Michael Jackson.” Greene pushed for the name change, and “Instantly, devotees of popular music stopped coming to Guinea Station….”

In late summer 2019, the NPS roadside signs along Interestate 95 were changed to “Stonewall Jackson Death Site.” “The name ‘Jackson Shrine’ was not helpful to visitors,” explained Hennessy. “The term ‘shrine,’ common for a historic site in the 1920s, is hardly ever used in that context today.”

Aside from the name, though, nothing else about the site has changed, Hennessy stresses: “It’s the only site that we have that’s focused on an individual. And secondly, it’s the site where our visitors have the most personal experience with our staff. It’s often one on one, or one and a family.”

Beyond the bronze plaques, granite markers, and brown roadside signs, Stonewall Jackson occupies a place somewhere between larger-than-life legend and roadside curiosity. The personal experience visitors can still have with Jackson’s personal story probably stands as the most fitting memorial of all.

Chris Mackowski is an author and editor-in-chief of Emerging Civil War (emergingcivilwar.com). He teaches writing at St. Bonaventure University.

_____

background history

In the late 1890s, the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac Railroad (RF&P) and the Confederate Memorial Literary Society created another roadside attraction for “Stonewall” Jackson, one that could be enjoyed by those traveling on the aforementioned railroad. Edmund T.D. Myers, a former Confederate officer and president of the railroad, worked with the society to build a 23-foot-high, 30-foot-square pyramid to indicate the location of Jackson’s position on Prospect Hill during the December 1862 Battle of Fredericksburg, just to the west of the rail line. Railcars brought 17 tons of granite to build the pyramid, a smaller version of the 90-foot-tall Confederate Memorial Pyramid that stands in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery.

Over time, however, the triangular pile of rock has become more associated with Union Maj. Gen. George Meade, as it sits on the ground where Meade’s 3rd Division of Maj. Gen. John Reynold’s 1st Corps temporarily broke through Jackson’s line during the afternoon fighting on December 13. Hence, the structure is now commonly known as the “Meade Pyramid,” and its association with Jackson is usually overlooked.

It is doubtful that many weary commuters or freight train conductors pay much heed to the monument—transferred to the National Park Service in 1953 as part of the Fredericksburg & Spotsylvania National Military Park—as they speed by on the modern tracks that now run on the path once used by the RF&P. And to get close to the monument, you have to bushwack your way from the battlefield’s Lee Drive, cross several sets of live railroad tracks, and then bushwack some more to reach the overgrown pyramid. Whether you appreciate the monument for Jackson or Meade, it’s best to do so from a distance. –Dana B. Shoaf

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.