Quick-thinking North Carolinian took command at a crucial point at Spotsylvania Court House

By 6 a.m., on May 12, 1864, news began to arrive in quick succession, some by telegraph and some by courier—the plan had worked. Major General Winfield S. Hancock’s 2nd Corps, Army of the Potomac, had smashed into the protrusion jutting out from the Confederate lines near Spotsylvania Court House, Va. Each report painted an even more devastating picture: The Rebel earthworks had been breached, Union troops were pouring into the salient, and thousands of prisoners had been captured, including two generals.

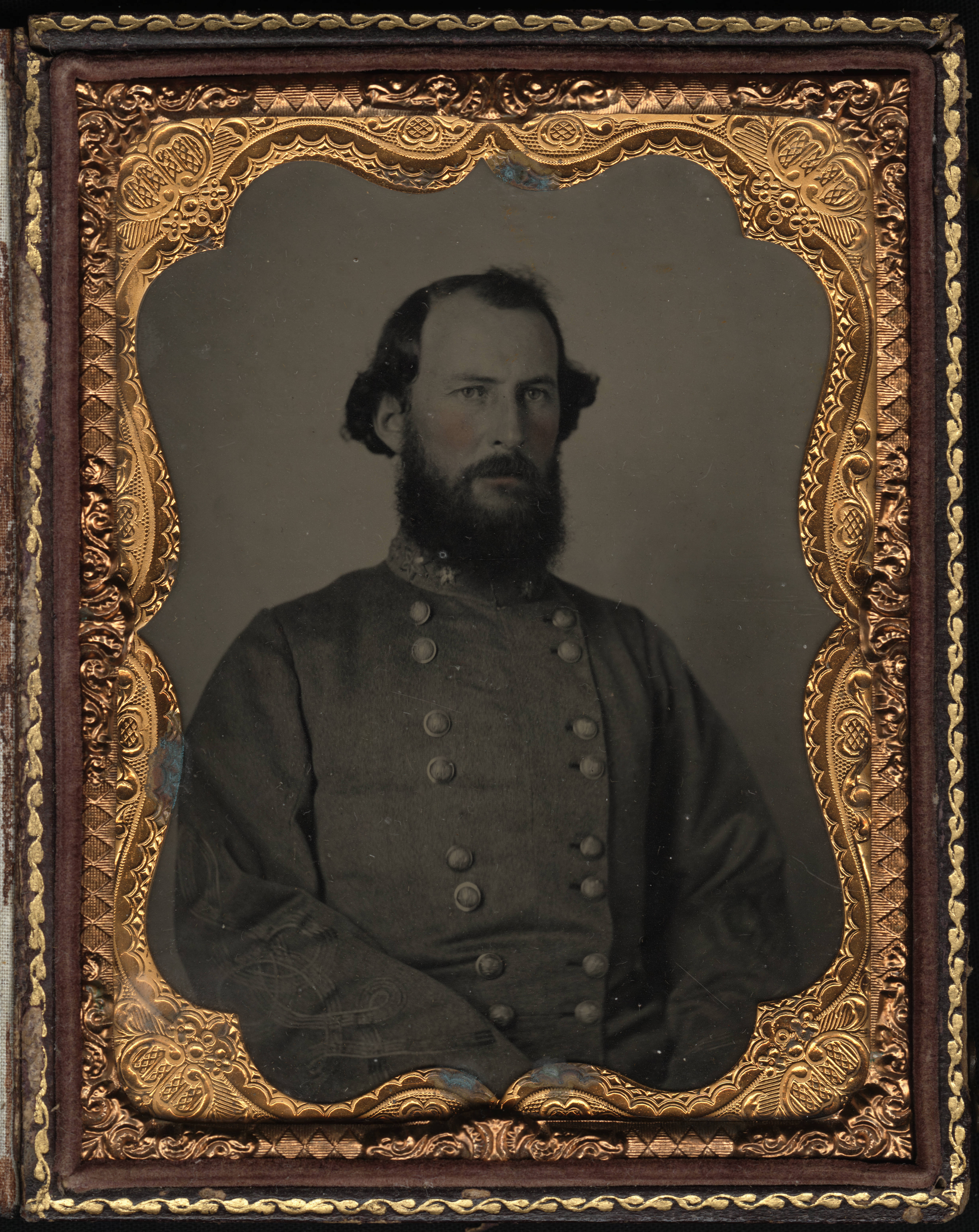

Union Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s staffers could not contain their jubilation. “Great rejoicing now burst forth. Some of Grant’s Staff were absurdly confident and were sure [Confederate General Robert E.] Lee was entirely beaten,” remarked Colonel Theodore Lyman of Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s staff. Lyman, however, was less sanguine than his associates: “My own experiences taught me a little more skepticism.” While the situation was critical for Lee’s army, Lyman’s reservations proved well-founded. By the time the fighting for the salient, called the Mule Shoe, ended nearly 24 hours later, a number of Confederate officers had distinguished themselves fighting to contain the breach in the Confederate lines. Colonel Bryan Grimes, commander of the 4th North Carolina Infantry, was one of those men. Not only did his quick action at a critical moment play a role in saving Lee’s army that disastrous day, it expedited the upward trajectory of his military career.

The second bloody battle of Grant’s 1864 Overland Campaign started on May 8. By the fourth day, Lee’s Confederate forces were established behind defensive earthworks north of the courthouse. Major General Richard Anderson’s First Corps held the right side of the line, with Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell’s Second Corps holding the center. The Third Corps, commanded by Maj. Gen. Jubal Early (in place of ill Lt. Gen. A.P.

Hill), curled back on the eastern extremity of the line. The most prominent feature was the salient that extended some 900 yards from Ewell’s position. The exposed position’s vulnerability eventually tempted Grant into a small-scale assault on May 10. Despite success by part of the Union force, a lack of coordination doomed the attack.

That failure convinced Grant that a larger and better coordinated attack could destroy the Confederate protrusion and open a gap in Lee’s entire line. Therefore, he ordered a second, and much larger, assault to begin in the predawn hours of May 12.

The plan appeared simple: Mass the 2nd Corps in the woods behind the Brown home, roughly three-quarters of a mile from the head of the Confederate salient, then unleash the men across the open field separating the two points. If all went as planned, other Union forces, including the 9th Corps attacking the eastern base of the salient, would prevent Rebel reinforcements from shoring up the exposed bulge in their lines. With luck, the Confederate lines would be cleaved open.

The salient was manned by the divisions of Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson, Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes, and Brig. Gen. James H. Lane’s Brigade of Maj. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s Division. Brigadier General John B. Gordon’s Division was positioned across the base in reserve.

The rain-soaked Confederates were at first unaware of the danger. Lee, in fact, was so convinced the Union forces were withdrawing that he pulled artillery from the salient. When Johnson received reports of troops on his front, he requested the guns be returned, but it was too late. Shortly after 4:30 a.m., Hancock’s men crashed out of the woods north of the Brown house and into the open field before the Confederate defenses.

Although some of Johnson’s troops heard the preparations and were waiting to see what developed, the darkness and low fog obscured their view. Even worse, they were unable to fire an effective volley because the rain had soaked much of their powder. Within 90 minutes, the Federals had breached the Rebel line and captured Johnson and 2,000 of his men, including one of his brigade commanders, Brig. Gen. George H. Steuart. It was this news that caused the excitement at Grant’s headquarters. The moment was critical: If the attack couldn’t be stopped and the breach sealed, Lee’s army would be split in two.

After the devastation of Johnson’s Division, Rodes moved his brigades to meet the Union troops pouring deeper into the narrow Confederate position. Gordon launched a counterattack, which stabilized parts of the original Confederate positions, leaving Rodes to drive the enemy from the western portion of the salient. Rodes pulled Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Ramseur’s Brigade from its place down his line and ordered an attack on the increasingly disorganized Federals.

Ramseur ordered his men “to keep the alignment, not to fire, to move slowly until the command ‘Charge,’ and then to move forward on the run…and not to pause” until they had retaken the Confederate lines. Before Ramseur could give the order, however, he was wounded and temporarily incapacitated. Realizing that speed was essential and there could be no delay in launching the attack, the 35-year-old Grimes took action and yelled “Charge!” in his commander’s place. When Ramseur returned to command after recovering, he was quick to praise Grimes’ initiative at “exactly…the right time.”

The counterattack succeeded in pushing Hancock’s men to the opposite side of the earthworks. For the next 20 hours, the two sides slugged it out. Finally, after 3 a.m., Lee ordered Rodes, Gordon, and the remnants of Johnson’s Division to fall back. By that time, the Mule Shoe was a ghastly scene of piled bodies. One of Grant’s officers was appalled: “Rank after rank was riddled by shot and shell and bayonet thrusts, and finally sank, a mass of torn and mutilated corpses.” As the exhausted Confederates staggered back to their new lines, “General Lee rode down in person to thank the brigade for its gallantry,” telling Grimes’ men “they deserved the thanks of the country” for saving his army. But Grimes’ quick decision provided only temporary salvation. Grant simply shifted to the east, forcing Lee to do the same, inching ever closer to Richmond.

Five weeks after the Mule Shoe, Grimes was promoted to brigadier general, dating to May 19. Although his Spotsylvania feats finally led to his general’s commission, there’d been calls for his promotion since the previous year. The last 11 months of the war, Grimes continued his solid leadership, notably in the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. In February 1865, he was promoted to major general (the last such appointment in Lee’s army) and was there at the end at Appomattox Court House, leading a skeletal division in the Second Corps.

James Robbins Jewell writes from Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.