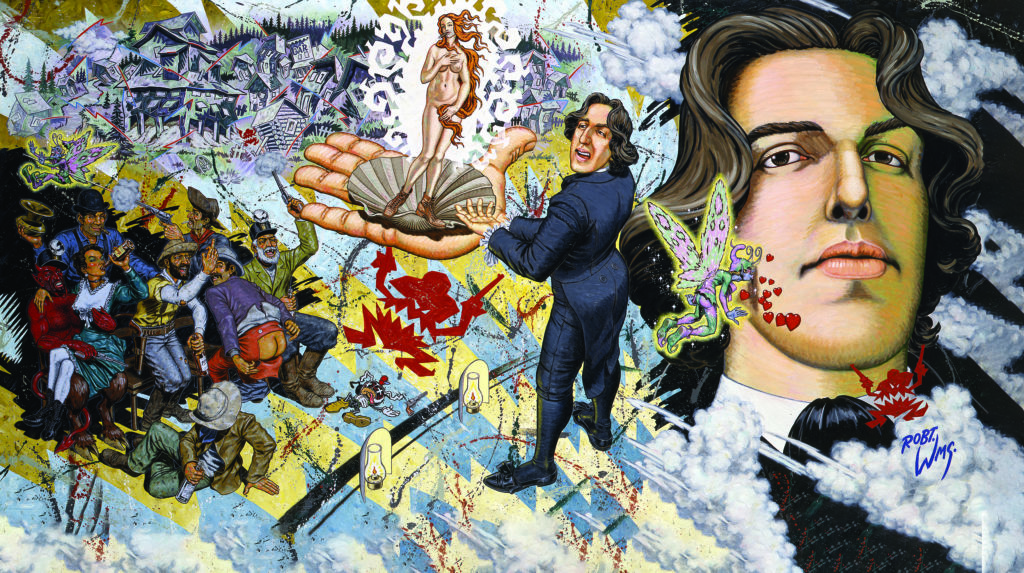

Oscar Wilde came to conquer America with an arched eyebrow and a saucy demeanor

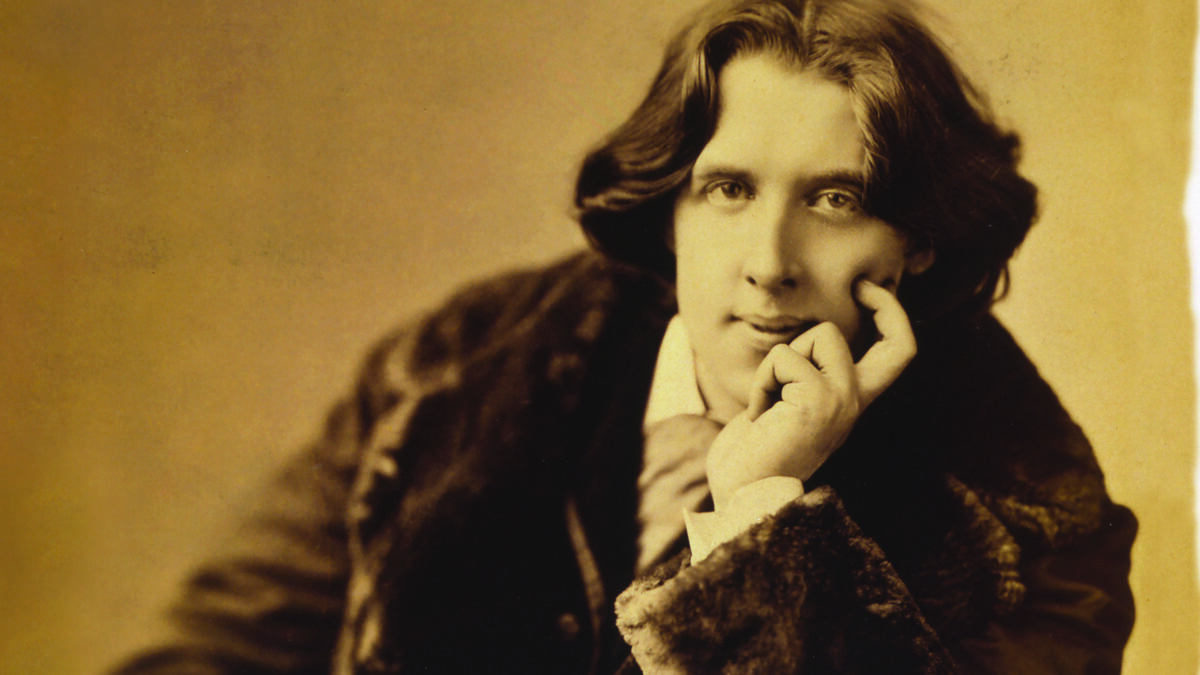

Oscar Wilde arrived in the United States on January 3, 1882, wearing the extravagantly flamboyant clothing that would soon make him famous—lavender trousers, frilly white shirt, blue scarf, green coat trimmed with seal fur, and a turban-like hat that perched atop his shoulder-length brown hair.

Newspaper reporters covering the Irish writer’s arrival thought he dressed funny and took careful notes on his attire. They also thought he talked funny. “His manner of talking is somewhat affected,” a reporter noted, “his great peculiarity being a rhythmic chant in which every fourth syllable is accentuated.” The New York Times reported that Wilde laughed funny, too: “His laugh was a succession of broad ‘haw, haw, haws.’”

Wilde was surprised by American newspaper writers’ descriptions of him but delighted to be the subject of their attention. He was a man who believed all publicity to be good publicity—or, as he famously put it later, “There is only one thing in the world worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about.”

In the next 51 weeks, Wilde became the subject of countless American conversations—never mind hundreds of articles, editorials, cartoons, and songs—as he zigzagged the country, traveling 15,000 miles, delivering nearly 150 lectures, and conducting more than 100 interviews with reporters, some of whom mocked him as a “sissy,” “an ass-thete,” and a “long-haired what’s it.” On his wild, zany circuit, Wilde ate gargantuan meals, drank copious quantities of whiskey and wine, visited a silver mine and an opium den, got fleeced, and hobnobbed with Walt Whitman and Jefferson Davis.

“How do you like our country?” a reporter asked the traveler two months into his journey.

“I am lost in wonder and amazement,” Wilde replied. “It’s not a country but a world.”

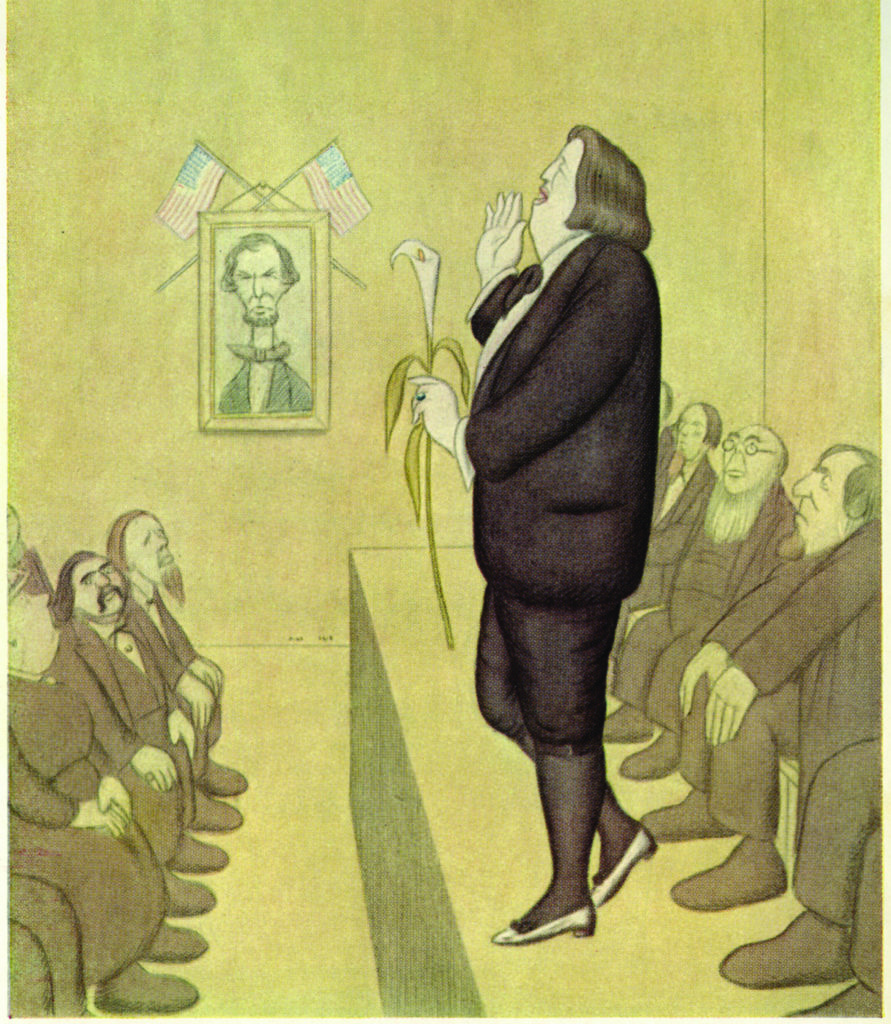

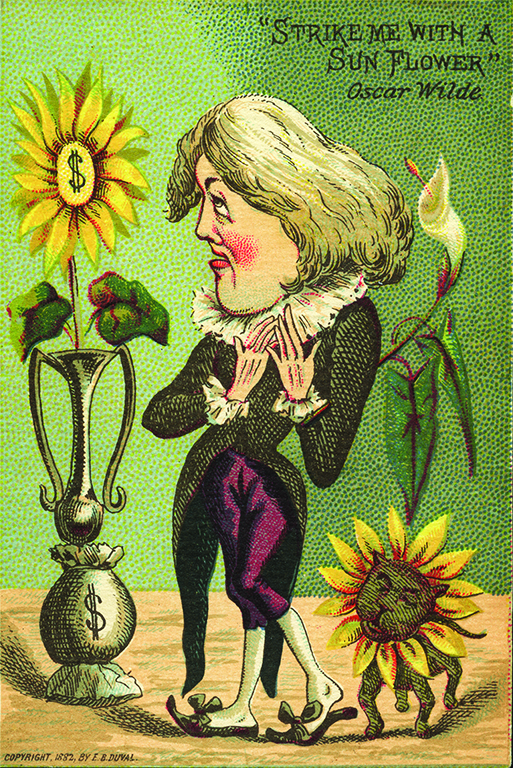

More than a century after his death, Oscar Wilde is famous for his bon mots, his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, and his play The Importance of Being Earnest. He’s also a legendary gay martyr, imprisoned in England for two years at hard labor for the crime of “gross indecency.” But in 1882, that was all in the future. Wilde was 27, a Dublin-born Londoner who had written only an unproduced play and a self-published book of poems. Even so, 6’3” and broad-shouldered, he cut quite a figure in the British capital’s artsy salons with his dress and his deportment, sometimes carrying a lily or a sunflower and once appearing at an art exhibit wearing a live snake as a scarf. He proclaimed himself an aesthete who lived for beauty and he dazzled dinner party companions with observations like “I can resist everything except temptation” and “Don’t be led astray down the path of virtue.”

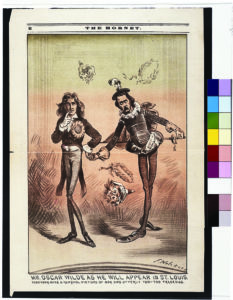

Wilde craved attention—and got it aplenty. British humor magazine Punch caricatured him. In 1881, W.S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan, composer and writer of the hit comic operettas H.M.S. Pinafore and The Pirates of Penzance, created a kindred satirical vehicle, Patience, or Bunthorne’s Bride, which satirized aestheticism, a social movement of which Wilde was a pillar. The cast of characters included the eponymous protagonist, a flower-toting Wildean fop of a fellow who sings, “I’m an aesthetic sham.”

When the operetta proved a smash hit in London, producer Richard D’Oyly Carte booked Patience into New York City’s Standard Theater. D’Oyly Carte proposed to send Wilde himself to America to deliver lectures, dazzle the Yanks—and promote Patience.

Wilde eagerly agreed, but he had no intention of promoting a production that mocked him. What he was planning to promote was himself.

“Somehow or other, I’ll be famous,” he said, “And if not famous, I’ll be notorious.”

While Wilde was sailing the Atlantic, swigging Champagne and amusing fellow passengers in the SS Arizona’s saloon, Colonel W.F. Morse, a New York promo man, was booking lectures for him and filling reporters’ ears with tales of Wilde’s eccentricities.

He was the dandy Patience satirized, Morse promised, a flower-sniffing freak given to preaching England’s “latest form of fashionable madness”—aestheticism, in Morse’s words the “gospel of morbid languor and sickly sensuousness.”

Always eager to mock pretentious Brits, American newsmen flocked to meet Arizona at the dock, mobbing Wilde as he watched a porter toss his suitcases into a coach. A scribe asked the writer why he’d come to America.

“I am here to diffuse beauty, and I have no objection to saying that,” Wilde answered. “I say, porter, handle that box more carefully, will you?”

“What is your definition of aestheticism?” the journalist asked.

“Aestheticism is a search after the signs of the beautiful.”

A reporter inquired about Patience.

“I fail to see its point, sir, but think it a very pretty opera with some charming music,” Wilde said. “As a satire on the philosophy of the beautiful, sir, I think it is the veriest twaddle.”

Obviously, Oscar Wilde wasn’t cut out for promoting the play, but for promoting himself.

Morse rescued Wilde from the press, hustling him to Delmonico’s, the fanciest restaurant in Manhattan. Two days later, the advance man escorted his client, clad in fey aesthetic garb, to a reception. At the event Wilde was feted by New York’s mayor, two prominent ministers, and many rich women eager to discuss art with an authentic aesthete. One sought advice on arranging decorative screens in her home.

“Why arrange them at all?” Wilde asked her. “Why not just let them occur?”

After the party, Wilde, accompanied by several matrons and a New York Tribune reporter, traveled to Broadway to take in Patience. Audience members turned to gawk as he arrived.

He’d seen the operetta twice in London and knew exactly how he’d take revenge. After the actor playing Bunthorne finished the song featuring the lyric “I am an aesthetic sham,” Wilde struck.

“As the whole audience turned and looked at Mr. Wilde,” the Tribune reported, “he leaned toward one of the ladies and said with a smile while looking at Bunthorne, ‘This is the compliment that mediocrity pays to those who are not mediocre.’”

Touché! Take that, Gilbert and Sullivan!

Oscar Wilde had arrived. Utterly unknown a few days earlier, he became a media sensation. The New York papers covered his every action. Those accounts were reprinted nationwide, making reporters across America eager to cover him on his swings through their towns. And Morse had booked Wilde to lecture in dozens of towns.

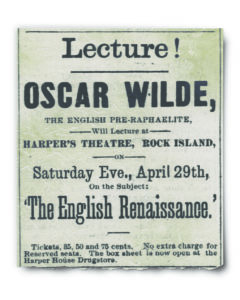

The man of the moment was to deliver his first discourse on January 9 at Manhattan’s 1,250-seat Chickering Hall. Morse’s hype had paid off: The auditorium was sold out and scalpers were hawking tickets for $2, twice face value. Wilde, who had never given a lecture in his life, hadn’t bothered to write one, either. Between social engagements, he dashed off a soliloquy on “The English Renaissance.”

On the appointed evening, the towering Wilde strolled onstage at Chickering Hall wearing black silk knee-breeches, black stockings, a starched white shirt garnished with a diamond, a black velvet jacket with lavender satin piping, patent leather shoes, and white kid gloves. “Among the many debts we owe to the supreme aesthetic faculty of Goethe…” he began in a monotone. Droning on, he elucidated his aesthetic philosophy, invoking Plato, Homer, Chaucer, Michelangelo, Byron, and Baudelaire. When he finished his esoteric oration, the audience applauded, probably not having grasped much of what he’d said. “The craze over Oscar Wilde received a fatal blow last night,” the New York Evening Graphic reported, because his audience realized that “they had been duped into aiding a young Irishman to make a pot of money.”

Actually, Wilde’s popularity soared, especially among the wives of Manhattan’s Gilded Age tycoons, a demographic craving the European culture Wilde embodied. Soon, invitations to soirées at fashionable mansions were swamping him. “I am torn to bits by Society,” Wilde wrote to a friend. “Immense receptions, wonderful dinners, crowds wait for my carriage. I wave a gloved hand and an ivory cane and they cheer.”

After two weeks of adulation in Manhattan, Wilde crossed the Hudson and set out to conquer the rest of America, which proved tougher than he expected.

In Philadelphia, he reprised his “English Renaissance” lecture, this time before an audience “so cold,” he lamented, that he considered “stopping and saying, ‘You don’t like this and there is no use of my going on.’” A reviewer described Wilde as “a weak, vain, pretentious crank.”

Further south, a front-page cartoon in The Washington Post depicted Wilde sniffing a sunflower beside an ape-like beast. “We present in close juxtaposition the pictures of Mr. Wilde of England and Mr. Wild of Borneo, who, judging from the resemblance, is undoubtedly kin,” the image’s caption read.

At Boston’s Music Hall, Wilde watched from the stage as Harvard students wearing long wigs, knee breeches, and colorful ties paraded down the venue’s center aisle, sniffing sunflowers. “I am impelled for the first time in my life,” Wilde told the capacity crowd, “to breathe a fervent prayer: ‘Save me from my disciples.’”

In New Haven, Connecticut, the next night, Yale students replayed the Harvard boys’ stunt. At the University of Rochester, students convinced a janitor to march into the hall in blackface, wearing a swallowtail coat with a sunflower pinned to the lapel and waving a white-gloved hand. The prank caused such commotion that cops were summoned.

If Wilde’s lectures weren’t universally beloved, at least the wealthy and the arty seemed eager for his company. In Washington, DC, a judge invited him to a reception at which he was introduced to several senators and the novelist Henry James, who later described Wilde as a “fatuous fool.” In Boston, Julia Ward Howe, author of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” invited her fellow celebrity writer to a fête where he met art collector Isabella Stewart Gardner and poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

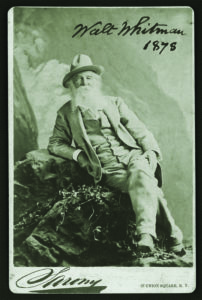

Wilde’s most moving encounter was in Camden, New Jersey, on a visit to his literary hero, Walt Whitman. “I come as a poet to call upon a poet,” he said when Whitman answered his door.

The two spent hours talking and drinking Whitman’s elderberry wine. To Wilde’s rarefied palate, the homemade beverage was dreadful, but he didn’t mind. “If it had been vinegar, I should have drunk it all the same,” he told a friend, “for I have an admiration for that man which I can hardly express.”

Cleveland, Chicago, Salt Lake City—as Wilde roamed west, he switched lecture topics, replacing “The English Renaissance” with “The House Beautiful,” an audience-friendly discourse on interior decorating. Like a 19th-century Martha Stewart, he dispensed domestic wisdom. Candlelight is more beautiful than gaslight, he proclaimed, and tile floors more charming than carpets. But hat racks are “hideous,” wallpaper “gives one the impression of living in a paper box,” and mass-produced furniture is “bloodcurdling evidence of barbarism.”

In city upon city, reporters knocked on his hotel room door, requesting interviews and asking questions ranging from “What is art?” to “How much do you make a night?” At first the phenomenon baffled him—“We have no interviewing in England,” he said—but he warmed to the task of spewing opinions. On art: “We can live without art but we cannot live with bad art.” Childrearing: “The child must be taught by constant association with beautiful things.” Women’s clothing: “Too somber. Many bright colors should be worn.” Men’s clothing: “Velvet should be chosen,” not broadcloth, which is “devoid of beauty.” Bad manners: “The most painful defect in American civilization.” And American women: “I see a quantity of beautiful young girls…but there are few handsome matrons.”

Wilde took mischievous joy in insulting American landmarks. He described Niagara Falls as “a vast unnecessary amount of water going the wrong way” and proclaimed that Salt Lake City’s Mormon Tabernacle reminded him of “a soup kettle.” He found Cincinnati hideous: “I wonder why no criminal has ever pleaded the ugliness of your city as an excuse for his crimes.”

To several interviewers, he grumbled about a small Illinois town’s name. The very sound of “Griggsville” offended his refined sensibilities. “Griggstown” and “Griggs” were acceptable, he told a reporter, but not “Griggsville.”

“Is that not the ultimate in vulgarity?” he asked. The reporter mentioned Western towns with names like Murderer’s Gulch and Hangtown. “They at least convey something of interest,” Wilde replied. “But in such a name as Griggsville, there is nothing but utterly unmitigated and offensive vulgarity. Ugh.” With that, the reporter noted, “the aesthete’s velvet coat shook with the violence of his emotions.”

Wilde’s mood brightened when he reached San Francisco. It was late March and his beloved flowers were blooming. He checked into the luxurious Palace Hotel and attended an opera. At the curtain call, he tossed the prima donna a bouquet. One night, after he had lectured, two police officers and a reporter escorted him around Chinatown, visiting flophouses, gambling joints, and opium dens.

“This,” he said, “is just like a chapter from The Arabian Nights!”

On April Fool’s Day, members of the Bohemian Club, curious to see if the dandy could hold his hooch, invited him for a night of serious drinking. Wilde could, and he did, and by the time he sauntered jauntily into the dawn, many a Bohemian had passed out drunk. Impressed, the club commissioned an oil portrait of the visiting “three-bottle man.”

“California is an Italy without its art,” Wilde intoned as he made his way east. In Denver, he spoke in the Grand Opera House while a group of prostitutes gathered nearby, wearing knee breeches and flowered hats in his honor. “We know what makes a cat wild,” a hooker told a newsman. “But what makes Oscar Wilde?”

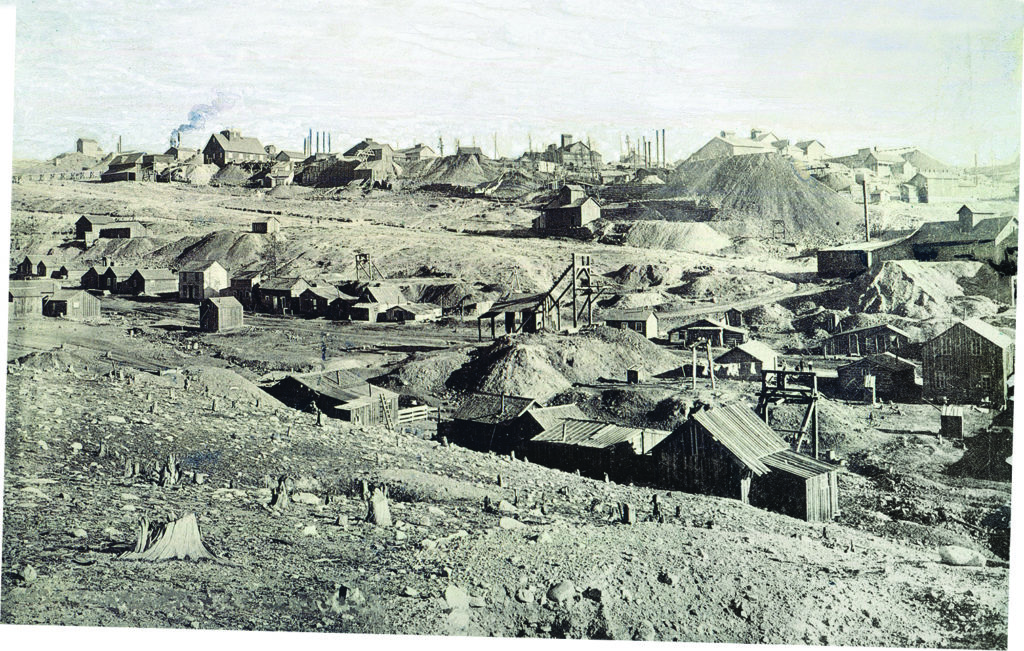

From Denver, he traveled to Leadville, Colorado, a mining town famous for vice and violence. After discoursing on “The Decorative Arts,” Wilde accepted an invitation to tour a silver mine and rode hundreds of feet into the earth in a metal ore bucket. When he arrived at the bottom, visibly spooked, miners soothed him with whiskey, then handed him a jackhammer so he could drill into an ore vein. He stayed until dawn, drinking and chatting with the miners. “They are cordial and generous and not at all rough,” he reported. “It was one of my most delightful experiences.”

Kansas, Missouri, Ohio—Wilde lectured all spring, returning to New York, then orbiting through Canada before undertaking a long tour of the American South. He entertained romantic notions about the region, likening the secessionist cause to his native Ireland’s independence movement. “It was a struggle for autonomy, self-government for a people,” he said, apparently forgetting about slavery.

Wilde toured New Orleans with former Confederate general P.G.T. Beauregard. In Mississippi, he arranged to visit former Confederate president Jefferson Davis, which shocked some Davis admirers. Why, asked Alabama’s Selma Times, would “the grand Southerner” deign to meet this “pseudo-fanatical, long-haired aesthetic humbug?”

Wilde and Davis did seem an odd match. They met at Davis’s plantation and dined with his wife and daughter. Whatever they discussed—The Battle of Vicksburg? The beauty of sunflowers?—is lost to history. “He impressed me very much as a man of the keenest intellect,” Wilde said later. Davis, 75 and frail, was less enthralled. He excused himself early and went to bed, claiming illness.

“I did not like the man,” the old secessionist told his wife.

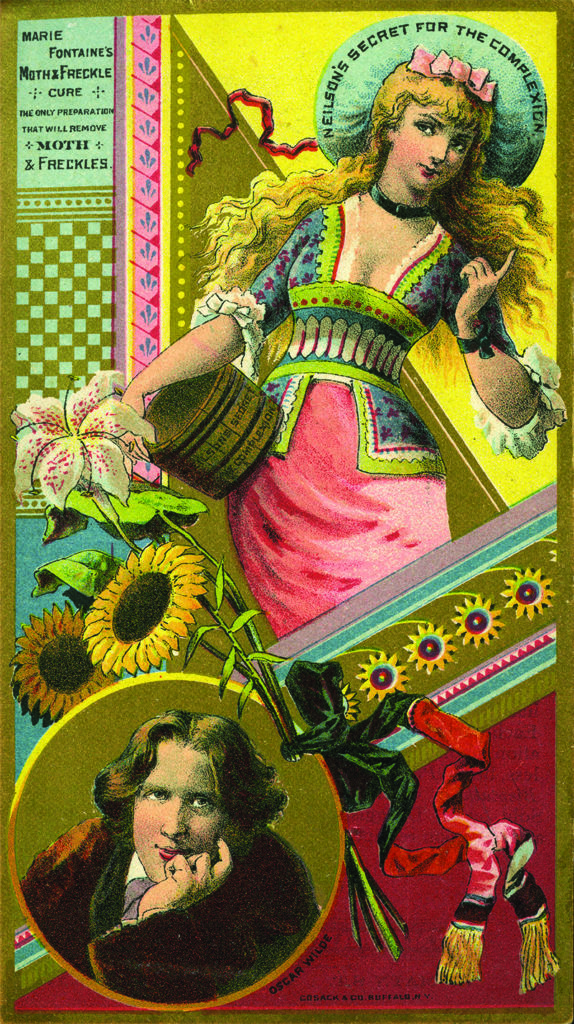

After a second round of appearances in New England, Wilde returned in mid-October to New York City, inspiring a Tribune headline: “Oscar Wilde Thoroughly Exhausted.” True, but he was also rich and even more famous. Lecturing had earned him more than $10,000—today, $250,000-plus—and made him a household name, inspiring popular songs about him and unauthorized use of his picture in advertisements for products ranging from cigars to stoves to “Mme. Fontaine’s Freckle Cure.”

Wilde hung around New York for two months, attending plays and partying with actresses and literary folk. On December 14, a confidence man lured him into a crooked dice game. Wilde started out winning but ended up skinned to the tune of $1,160—which he paid by check, enabling him to stop payment. Walking to a nearby police station, he announced, “I’ve just made a damn fool of myself.” From a book of mug shots, he identified the bunco artist, one “Hungry Joe.” On December 27—51 weeks after arriving stateside—Wilde sailed to England, where he resumed lecturing.

He’d learned something on his American tour—forget big ideas, keep it amusing—and so his set-piece “Impressions of America” skipped grandiose pronouncements in favor of amusing observations. “America is the noisiest country that ever existed,” Wilde said, a place where “everybody seems in a hurry to catch a train.” Americans have a “sound, practical sense” that is “not favorable to poetry or romance.”

Alamy Stock Photo)

He compared the prairie to “a piece of blotting paper” and pronounced himself “disappointed” in Niagara Falls: “Every American bride is taken there, and the sight of the stupendous waterfall must be one of the earliest, if not the keenest, disappointments in American married life.”

Through “Impressions” Wilde kept his patter light—“I know but little about the country,” he admitted—and made no mention of America’s grand experiment in democracy until his final sentence: “It is well worth one’s while to go to a country which can teach us the beauty of the word Freedom and the value of the thing Liberty.”

This story appeared in August 2020 issue of American History.