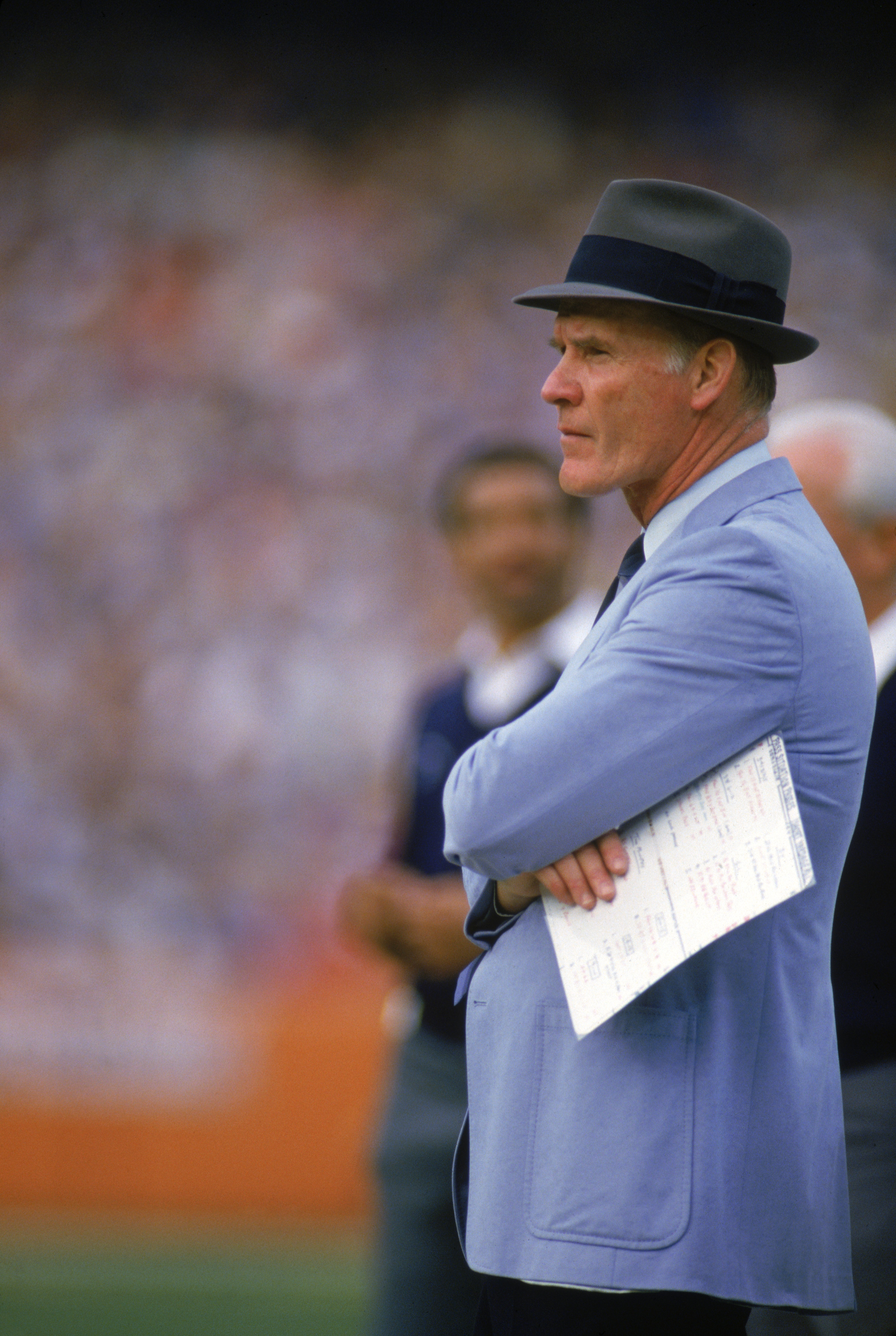

DO YOU REMEMBER how smartly the man dressed? That custom-tailored jacket, the perfectly knotted tie and, always, that trademark fedora perched at just the right angle? Do you remember Dallas Cowboys head coach Tom Landry, watching from the sidelines on any given NFL Sunday from 1960 to 1988? If you do, then you might also remember the man’s classic demeanor: calm, stoic, concentrating. His players might be celebrating the go-ahead touchdown, but Landry was all business. Getting ready for the next series, focusing four plays ahead, the football grandmaster who led America’s Team to two Super Bowl championships in the 1970s. But you would have had no reason to suspect then that the veteran NFL player and coach was also a veteran of 30 combat bomber missions in World War II, or to have envisioned the unflappable, iron-jawed head coach as a stunned young pilot in the cockpit of a B-17 bomber.

“I think the thing that sticks out the most is that I was not prepared for all of it,” Landry told me in a 1981 interview I conducted with him for a documentary on the B-17. “I’d been one semester at the University of Texas. I was called up in February of ’44, when I was 19 years old. And, boy, to go from there—from Mission, Texas—to Europe to fly a bomber… I just really didn’t know what was going on. I just flew my missions, did my job, and came home.” That was four decades ago, but I find I still think of his story often—all the more so after the recent death of my own father, who had served as a naval intelligence officer in World War II.

Many who fought in the war have memories they speak of modestly—if they can be coaxed to tell their stories at all. For some these recollections are just too vivid, coming back to them at night in terrible dreams or, when spoken aloud, told through tears with halting voices. They won a global war, came home, went to college on the G.I. Bill, and built a country. And whether they speak of their experiences or maintain a dignified silence, their lives were shaped by the things they saw and did at war—the things they lived through, which so many of their comrades did not.

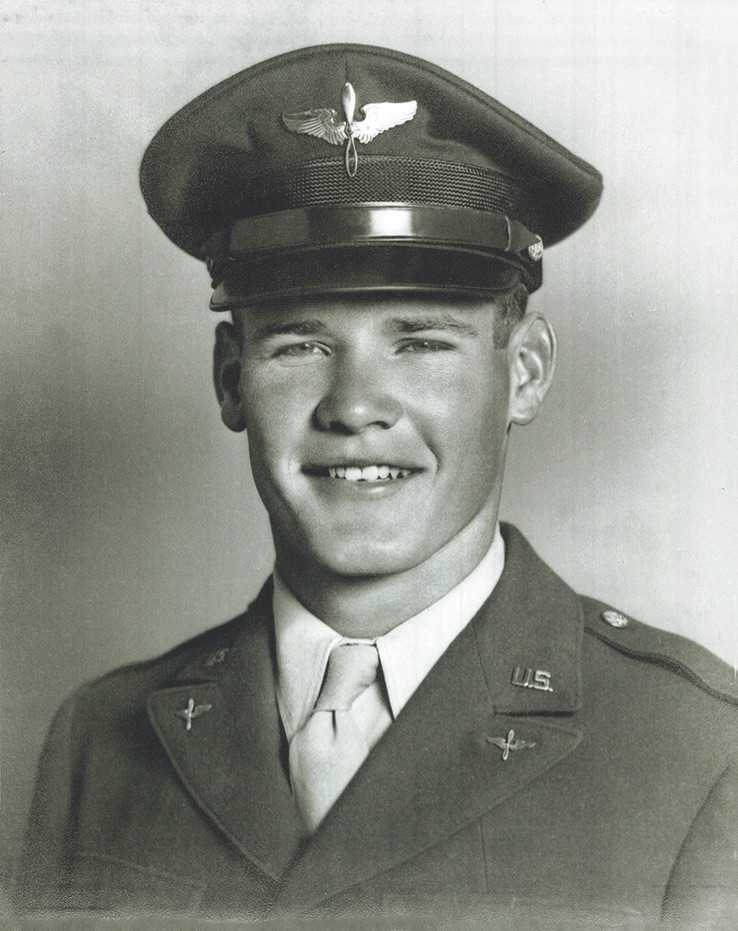

THE WAR WAS PERSONAL for Landry in a very painful way. His older brother Robert, whom he idolized, was killed when a B-17 he was ferrying to England exploded over the North Atlantic in September 1942. Robert Landry and his crew were listed as MIA for several weeks; the wait must have been unbearable for his family. Not long after they received the fateful telegram around Thanksgiving 1943, Landry was called up and sent through basic and pilot training, which had him hopscotching from base to base around the country: Wichita Falls, San Antonio and Lubbock, Texas; Wilburton, Oklahoma; and finally Sioux City, Iowa, where Landry trained to fly the B-17 Flying Fortress. The training transformed him from University of Texas-Austin football player Tommie Landry into Second Lieutenant Thomas Wade Landry, 860th Bombardment Squadron, 493rd Bombardment Group, Eighth Air Force. From his days learning to fly the four-engine B-17 over America’s heartland to his experiences in the unfriendly skies of Europe, Landry grew to appreciate the Fortress’s legendary toughness.

“The B-17 was a great airplane,” Landry said. “It had a tremendous wingspan, and you could get a couple of engines shot out and still make it back on just two engines. The B-17 really saved a lot of American boys’ lives. It could get shot up pretty good before it would go down.”

After shipping out to England on the refitted luxury liner Queen Mary, Landry barely had time to learn his way around his airbase near Ipswich, northeast of London on the River Orwell. He took the right seat on November 21, 1944, flying copilot out of Ipswich to bomb the Leuna Werke synthetic oil refinery at Merseburg, in central Germany. Leuna Werke was a vital producer of fuel for the Nazi war machine, and as such, was heavily defended by more than 600 antiaircraft batteries. Bomber crews had nicknamed the region “Murdersburg.”

“I never saw anything like that,” Landry recalled. “When we got there, it was just a cloud of black smoke from flak as you headed into the target. And the flak would pound you around pretty good. It was like flying inside a thundercloud. You’d just make the run, drop your bombs, and get out of the target area as quickly as you could.”

He made it sound so simple: just drop the bombs and leave the target area. But so much more went into the job. Like Landry’s jaunts to the oil fields in Czechoslovakia—six hours out, six hours back, just to make a two-minute bomb run in a bumpy, bitterly cold aircraft that could turn into a coffin at a moment’s notice. From a vantage point some 40 years later, Landry spoke of those days like just another one at the office. As we sat in his actual office, where I had interviewed him numerous times over the decade I covered the Cowboys as a sportscaster, I saw a different side of Landry. With a sterling silver Super Bowl trophy gleaming in one corner, he vividly recalled one story after another. We wound up spending nearly an hour and a half discussing his personal war memories.

“We tore up one ’17 pretty good when we ran out of gas,” Landry noted, describing an eventful bombing mission over Kolin, Czechoslovakia, on April 18, 1945. “Our alternative airfield was in France, because at the time we didn’t have enough gas left in the tank to make it across the Channel to England. So we went to our alternate, and when we got there it was zero visibility—just totally fogged in. I don’t know how many hundreds of planes might have gone down that day trying to find their alternate field. We were skimming the treetops and the roofs of the houses, trying to find an airfield. We’d know about where it was from our navigator; he’d tell where it was, and then we’d have to drop down through the fog to find the field. Well, finally we just ran out of gas. We moved everybody to the back of the plane, cut the motors, and looked for a field to land in. But fields over there are lined with trees, not fences. We overshot the field we picked and went right into the trees. The trees knocked the wings off, and when the plane stopped, there was a tree trunk sitting about a foot in front of us where we sat as pilots. Everybody just got up and walked off the plane. Nobody got hurt because there was no gas to explode.”

MAYBE NOW YOU REMEMBER Tom Landry of the Dallas Cowboys just a little better. Maybe you remember rooting for, or against, his team. Either way, maybe you could never understand how the man could remain so calm as 70,000 fans screamed at the top of their lungs and his players tried to execute his complex Flex defense, the big men up front moving to fill the gaps in the line instead of chasing the ball—the exact opposite of what their instincts told them to do. In a time long ago, under much more pressure, Landry had to fight his own instincts during the return from another bombing run over the Netherlands.

As he did for nearly all his 30 missions, Landry flew as copilot. (When his aircraft was designated to lead the mission, the group commander took the right seat, relegating Landry to the top turret gun.) But this time, the engines shut down, and Landry and his command pilot issued orders to their crewmates to bail out. The crew prepared to jump, and the hatch was opened. But just before he left the cockpit, the quick-thinking Landry tried one last-ditch maneuver: he reached down and flipped a fuel mixture switch, which instantly brought the engines back to life. The flight back to Ipswich resumed with everybody still on board.

So really… how tense do you get on third-and-two?

On mission days the pilots crowded into the briefing room at Ipswich, a Quonset hut where large maps at the front displayed the day’s chosen target area. Landry and his crew leader, Captain Kenneth Sainz, were briefed on the plan of attack along with the 860th Bomb Squadron’s other crews. Before the briefing began, the pilots bantered back and forth. It may have seemed lighthearted, but many of those in the briefing room on any given morning might not be there the next day, nor any day thereafter. That thought was never far from the pilots’ minds, the 19, 20, 21-year-old boys rapidly turning into men. More than once, the wait to get up into the skies was worse than the flying itself.

In December 1944 the Battle of the Bulge raged in and around Bastogne, Belgium, where German forces had surrounded the city. The dreadful winter weather—the worst in decades—prevented Allied aircraft from striking. Lieutenant General George S. Patton, there with his Third Army, ordered his chaplain to write a prayer asking for good weather. Landry may not have known about the prayer, but the bad weather was all too familiar to him.

“During the Battle of the Bulge I’ll bet we briefed as many as 20 days in a row, but we couldn’t get off the ground. You’d go out, you’d warm up your ship, taxi out, and then they’d scrub the mission. You couldn’t see your hand in front of your face. Too much fog. We just kept going through the same thing over and over, until we finally got up to bomb. And even then, we were bombing through clouds at targets. But that memory, of all those mornings we got up early and hoped we could get up to help the Allies who were surrounded, and we couldn’t even get off the ground.” Landry’s quiet voice went silent, and he looked off into the distance.

In football terms it could be said that Tom Landry got into the fight pretty late in the game. And in one sense, that late entry made the job of a bomber pilot in Europe a lot easier: at this point the dreaded Luftwaffe was now all but vanquished.

“By the time I got there, we’d see a few German fighters, but we pretty much had the Luftwaffe under control by then,” Landry added. “We were battling flak more than the Luftwaffe. We were never really attacked by fighter planes during our missions.”

But even in its final months, World War II was still a young man’s war. Young men have that sense of invulnerability: “It can’t happen to me.” Four decades past the war’s end, well into his football career, I asked Landry if he ever thought at the time how dangerous every takeoff, every mission, every landing they made could be. Did this scare him? Did he ever have second thoughts?

“Not at all. I could see myself doing it all again, sure. If our country was threatened the way it was at that time—goodness gracious, everybody just went to war. Whether you came back or not was not the important thing. So I could see myself doing it all again.”

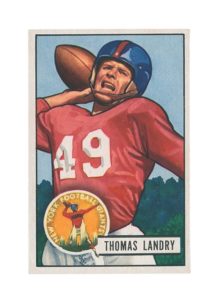

A MUCH-CHANGED Tom Landry came home after flying 30 missions, returning to his two great loves: Texas and football. He continued his education at the University of Texas-Austin, graduating in 1949 with a degree in electrical engineering. He also celebrated two bowl victories with the Longhorns, including the 1949 Orange Bowl. Not long after that game, he married his college sweetheart, Alicia Wiggs.

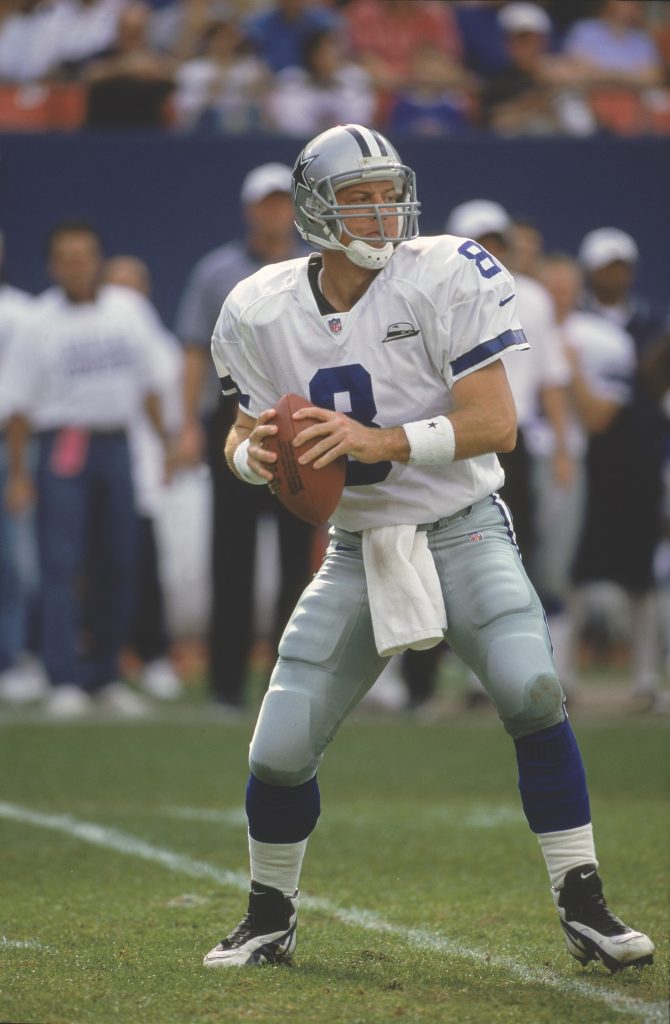

Landry’s football career began in earnest in 1950, when he joined the New York Giants as a defensive back; four years later, he became an assistant coach. When a new NFL franchise was granted to Dallas in 1960, Landry nabbed the head coaching job. It was a struggle from the start: there were lean losing seasons, not to mention a winless debut year. But with his engineer’s thoroughness and football genius, Tom improved the Cowboys season after season. In 1972’s Super Bowl VI, when Landry’s team beat the Miami Dolphins 24-3, the Dallas Cowboys finally shrugged off the sarcastic title of “Next Year’s Champions”—a nickname hung on them in the mid-’60s by a not-always-kind press corps. Five out of 10 Super Bowls in the 1970s featured the Dallas Cowboys, and in 1978 they beat the Denver Broncos 27-10 to win their second title under Landry in Super Bowl XII.

Of course, nothing lasts forever. After 29 years as the only head coach the Cowboys ever had—and following 20 consecutive winning seasons, an NFL record that still stands— Landry was fired when new ownership took over the team. He entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1990; in 1999 he was diagnosed with leukemia, and he died in 2000.

Arguably, a large portion of the football success of Tom Landry, and the Dallas Cowboys, was born in the cramped cockpit of a B-17—braving the skies over Nazi Germany, flying through deadly flak to bomb an oil field, living to fly another day. Toward the end of my 1981 interview with Landry, I asked him if all his wartime experiences accounted for why he never lost control of his emotions when his team faced a tough situation late in a game. He laughed and said, “Yeah, I guess it is.”

After his coaching days were over, Landry decided to obtain his private pilot’s license and return to the cockpit. He bought a single-engine Cessna so he could travel between Dallas and Austin, where he had a second home. In 1995 Tom and Alicia were en route to Austin in their Cessna when the engine failed just after takeoff. It’s tempting to wonder what ran through Landry’s mind during those dangerous minutes. Did his days in a B-17 cockpit flash before his eyes? Did he feel the same catch in his throat? Or did his engineer’s mind run down a mental checklist to try and solve the problem? We will never know what he was thinking. What we do know is that private pilot Tom Landry, cool, calm, and unflappable, landed his powerless Cessna in an open area in the city of Ennis, Texas. He put it down right next to the high school’s football field. ✯

This article was published in the February 2022 issue of World War II.