The Wehrmacht invaded Norway with the swiftness of a spring wind and violence of an eagle rending its prey. German Fallschirmjägers, making the first opposed airborne assault in history, landed at desolate Sola Air Station just after dawn on April 9, 1940. Behind them in successive waves came more than 1,000 Luftwaffe aircraft, six army divisions and a Kriegsmarine armada that included two of Nazi Germany’s most powerful battleships.

That same day Adolf Hitler’s military machine overran Denmark in a matter of hours, and by sunset it was well on its way toward securing a foothold in Scandinavia. The Norwegian army, only partially mobilized, was caught unprepared and overmatched in the mostly rural, mountainous countryside. Within days the survivors were marching with dejected stares, two abreast, on country roads. They were no longer free.

Britain responded immediately, sending the battleship Warspite and a flotilla of destroyers to the northern port of Narvik and landing an Anglo-French expeditionary force farther south.

But despite reinforcements and a delaying action by stubborn Norwegian forces, the invasion rapidly progressed. On April 26, less than two weeks after having landed troops, the British decided to abandon their crumbling position in the country. They’d fight on through May in a desperate struggle for Narvik, until the once bustling seaside community was reduced to smoldering ruins in the crossfire between British warships and land-based German heavy artillery. By June 10 it was all over.

But despite reinforcements and a delaying action by stubborn Norwegian forces, the invasion rapidly progressed. On April 26, less than two weeks after having landed troops, the British decided to abandon their crumbling position in the country. They’d fight on through May in a desperate struggle for Narvik, until the once bustling seaside community was reduced to smoldering ruins in the crossfire between British warships and land-based German heavy artillery. By June 10 it was all over.

For Belgium, the Netherlands and France it had only begun.

On May 10 the German blitzkrieg struck south, and Americans unfolding their morning papers were soon introduced to the likes of Heinz Guderian and Erwin Rommel. The summer of 1940 brought new emphasis and immediacy to the debate over the United States’ involvement in the widening war, and as voices grew louder on all sides of the political spectrum, an American literary icon was busy formulating his response.

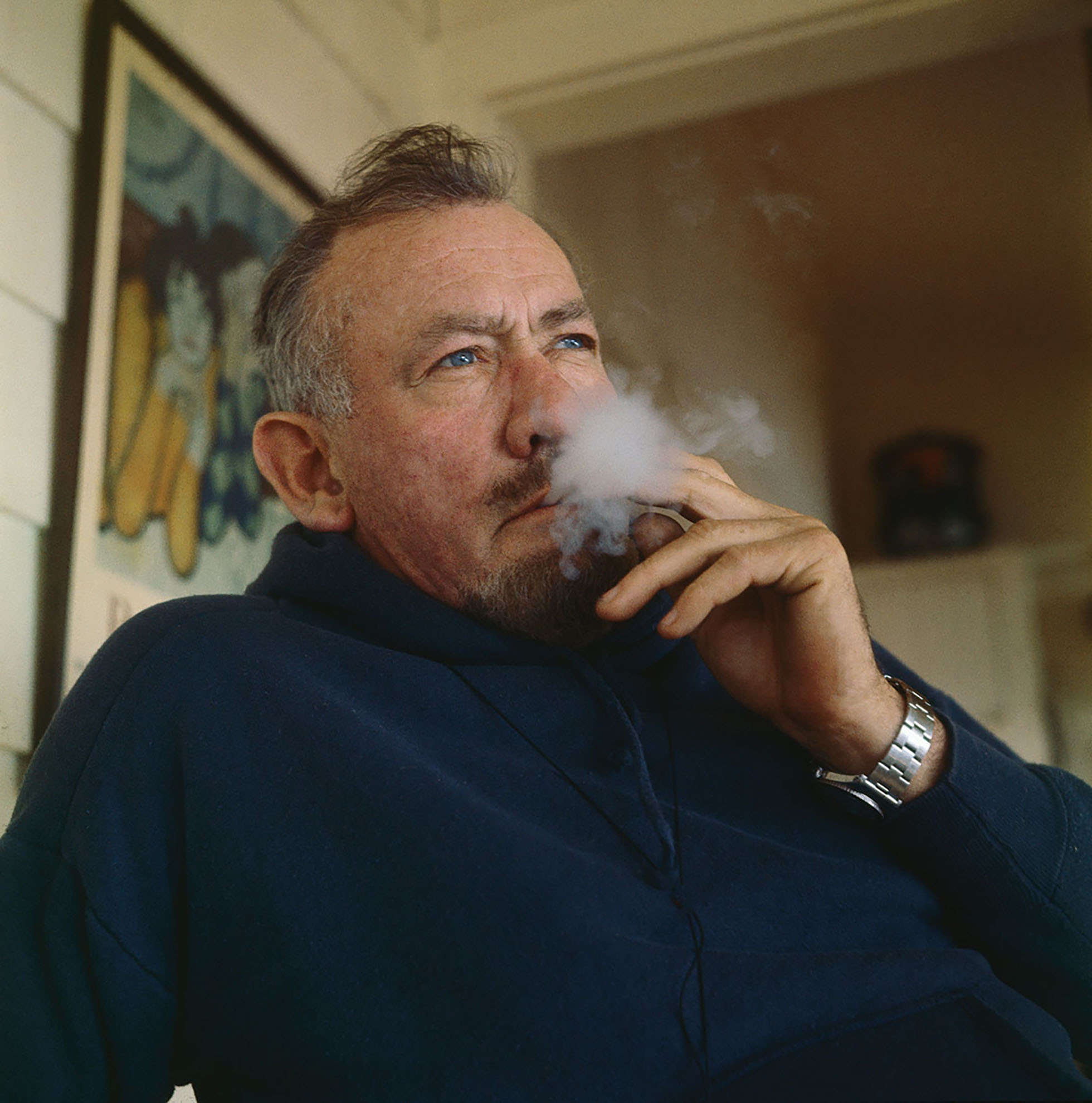

In the eyes of Depression-era Americans John Steinbeck might have seemed a curious first choice as a government propagandist. Already hailed for his “Dustbowl trilogy” of novels—In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937) and The Grapes of Wrath (1939)—the author and outspoken liberal had been a vocal critic of what he saw as the erosion of democratic values in California during the 1930s. In his estimation, with the introduction of corporate farming and a widening fear of communist influences, the state’s business leaders and politicians had begun to resemble the right-wing party bosses taking control across Europe.

In 1938 Steinbeck elaborated on his position in a letter in Writers Take Sides, a literary pamphlet published by the Communist Party USA’s League of American Writers in which prominent writers and social critics (among them Ernest Hemingway and Upton Sinclair) voiced their objections to the Nationalist rebellion of Generalissimo Francisco Franco in Spain. Steinbeck’s contribution to the volume was direct in its criticism of the situation in California: “We have our own fascist groups out here.”

Perhaps it was that view which made Steinbeck especially sensitive to the Nazi threat. While working on film projects in Mexico as the Germans were pinning the British and French against the sea at Dunkirk, Steinbeck witnessed firsthand Nazi propaganda efforts in Latin America. While Steinbeck likely overreacted to any potential German invasion from the southern border (there were only some 8,000 Nazi Party members in Latin America combined, or 12,000 fewer than the number of Americans who attended a 1939 Nazi rally at New York’s Madison Square Garden organized by the German American Bund), his concern for democracy was genuine. Before returning stateside, Steinbeck wrote his uncle Joseph Hamilton, head of information at the Works Progress Administration in Washington, D.C., declaring, “If [Nazi propaganda] continues, they will completely win Central and South America away from the United States.”

The celebrated author wasn’t just blowing off steam to a family member. Two days after France signed an armistice with Germany, Steinbeck wrote President Franklin D. Roosevelt of the need to employ “immediate, controlled, considered and directed” methods of propaganda. Two days after that, on June 26, 1940, Steinbeck had an appointment in the Oval Office.

There is no evidence the meeting produced anything more than a sympathetic, nodding FDR, but Steinbeck wasn’t dissuaded. He proposed various propaganda efforts over the coming months and together with friend Ed Ricketts sought to market them to both the government and the public. While the government didn’t warm to Steinbeck’s scheme of flooding the German economy with counterfeit currency, officials did find a role for the best-selling author.

Colonel William Joseph “Wild Bill” Donovan could not have been more the opposite of Steinbeck. Whereas Steinbeck was a Californian by birth, a liberal Democrat and a lapsed Episcopalian turned agnostic, Donovan was a wealthy New York attorney who had once aspired to be the first Roman Catholic president of the United States, on a Republican ticket. Donovan had also served in uniform. A World War I veteran, he had been wounded in action, awarded the Medal of Honor and been a feature character in the 1940 Warner Bros. war film The Fighting 69th.

Despite their differences, the two shared many of the same views with regard to Europe, as well as innovative, unconventional ideas for combating the Nazis.

Politically speaking, Donovan also had little in common with FDR, a former Columbia Law School classmate. But Wild Bill was a pragmatist, so much so that when the president was looking for a man to head a shadowy new intelligence and propaganda agency called the Office of the Coordinator of the Information (COI), he chose the decorated warrior-diplomat. As for when and where

Donovan and Steinbeck met, the details are murky. The only reference to Steinbeck found in Wild Bill’s correspondence is a letter from the novelist to Donovan shortly after the latter became head of COI. The letter, proposing the United States air-drop grenades into occupied countries for partisan use against the Germans, apparently went unanswered.

Nevertheless, Donovan employed all types of individuals in the COI, which in June 1942 ceded its intelligence functions to the new Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a predecessor of the CIA. New Dealers, labor activists and even communists were put to use (Donovan reportedly once said, “I’d put Stalin on the OSS payroll if I thought it would help defeat Hitler”), as were leading figures in politics, academia and literature. Among those with whom Donovan worked (and was often at odds) was liberal playwright and FDR speechwriter Robert E. Sherwood, who in his capacity as director of the Foreign Information Service (FIS) employed Steinbeck. It was probably through the FIS that Donovan encountered Steinbeck, who, according to biographer Lewis Gannett, suggested to the intelligence chief that the author draw attention to people in occupied countries by writing a story about the emerging resistance movements.

It was apparently a project Steinbeck had been mulling over since his initial meeting with FDR, one that had taken on new life when the author came into contact with refugees pouring in from conquered nations. Gripped by the accounts of individuals who “refused to admit defeat even when Germans patrolled their streets,” Steinbeck made use of his penchant for exploring the psychology of the common man by shifting his focus to the international stage. What he found, especially in his discussions with Norwegian refugees, was a pattern of initial confusion and collaboration, followed by restriction and sometimes brutal punishment that helped foment resistance movements.

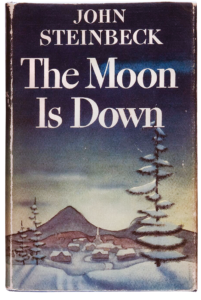

Drawing on a notion that people around the world shared certain “essentials” (as well as his lingering, and likely overblown, fear of the influence of the German American Bund), Steinbeck originally set his novella in the United States. But the FIS rejected the story out of concern it might demoralize the American public. Fortunately, Steinbeck didn’t have to go back to the drawing board, and with the encouragement of refugee contacts from Norway, Denmark, France and other nations under the Nazi boot, Steinbeck simply shifted the setting while retaining many of the same characters and themes. The resulting conquered nation, according to the author, was “an unnamed country, cold and stern like Norway, cunning and implacable like Denmark, reasonable like France.” By keeping the setting as vague as possible, Steinbeck hoped to create a work that could transcend borders and inspire resistance movements in multiple occupied nations. The title, pulled from the opening lines of Act II of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, encapsulated the novella’s theme: An invader (clearly Nazi Germany) had brought not only evil to a nation, but also a moral darkness across all of Europe.

Yet before the novella clandestinely reached the hands of those it sought to inspire, its author would first have to defend his work against a barrage of criticism from reviewers who believed his unsettlingly reasonable “invaders” undermined the very purpose of propaganda.

Steinbeck completed The Moon Is Down in early 1942. Published in the shadow of the American retreat from the Philippines, as well as Rommel’s approach to the Egyptian border, the novella came under the scrutiny of reviewers still uncertain of the war’s outcome. While some domestic critics were positive, grateful for an uplifting work that showcased American ideals of individual freedom and small-town democracy, many took issue with Steinbeck’s themes. For one, he had portrayed the implicitly German invaders—particularly their commander, Col. Lanser—as fair-minded human beings. Others criticized the author’s Pollyannaish insistence that good always triumphs over evil.

“[Steinbeck’s] form of spiritual patriotism is not only not enough but may even impede the war effort, because it fills us with a specious satisfaction,” critic Clifton Fadiman wrote in The New Yorker. “It seduces us to rest on the oars of our own moral superiority. Though an unabashed Steinbeck admirer, Fadiman couldn’t get past what he regarded as a fairy-tale treatment of the resistance movement in the novella, in which violence against the invaders is only alluded to in dialogue spoken by the principal characters, as if that were enough to bolster the spirits of the conquered. “We will, I fear, hardly be helped by the noble message in The Moon Is Down,” Fadiman concluded. “We can be helped only by the blood, toil, tears and sweat of which Mr. Churchill has spoken.”

Admirers of the ardently anti-fascist Steinbeck (whom the FBI and Army intelligence suspected of communist sympathies arising from his writings for and membership in certain organizations, as well as his activism against the Nationalist cause during the Spanish Civil War) found his rendering of the German soldiers naïve and unrealistic. With such characters as Capt. Bentick, described as “a lover of dogs and pink children and Christmas,” as well as the ever apologetic and polite Lanser, who excuses the occupation as “more a business venture than anything else,” Steinbeck’s invaders were lambasted in the New Republic as “Hamletlike Nazis.” Critic James Thurber wrote that if real German soldiers were anything like those in the novella, the Allies “will be able to rout the pussycats merely by shouting, ‘Boo!’” Even Hans Olav, a consular member of the Norwegian government-in-exile in Washington, D.C., found Steinbeck’s portrayal of the Germans “wide of the mark” and wondered why the writer seemed unwilling to paint his villains with the same disdain he’d aimed at their moral equivalents in books like The Grapes of Wrath.

Stung by such criticism, Steinbeck later explained he had rendered the invaders as regular men, “not supermen,” because that’s who they really were. Furthermore, rather than dwell on a portrait of evil, he wanted to focus the novella’s message on the durability of democracy and the concept of personal freedom when confronted with oppression. He refused to turn his villains into Hunlike caricatures, as so many other propaganda writers and directors had done. In many aspects Steinbeck’s rendering proved accurate—recent studies have shown the initial occupation of countries like Denmark and Norway was conducted with relative civility, including instructions for Wehrmacht troops to observe local customs and even pay for merchandise. Political exiles and the Allied press often exaggerated accounts of overt brutality, at least in the early months of Norway’s occupation.

Though Steinbeck didn’t immediately realize it, a larger debate was brewing in both Washington and New York in which Donovan’s vision of propaganda—that it be used as a weapon of subversion—was clashing with Sherwood’s insistence on spotlighting the “American way of life.” Steinbeck wrote more toward the latter, emphasizing what turned out to be a far more realistic portrayal of the average German soldier in occupied Norway. But his views didn’t square with those who recognized the world to be in a state of total war. Yet as 1942 marched toward 1943, and the balance of power began to shift, The Moon Is Down would have an impact where it counted—in occupied Europe.

“I am a little man, and this is a little town, but there must be a spark in little men that can burst into a flame.” Such are the words of Mayor Orden in the closing pages of The Moon Is Down. The story’s chief protagonist, mayor of the small “everytown” in Nazi-controlled Europe, Orden progresses from uncertainty over his response to the invaders at the start of the novella to a defiant, affirming embrace of resistance. Ordered by an indignant Col. Lanser to stop the spread of partisan attacks and logistical sabotage against the occupiers, Orden refuses on the basis of democratic ideals. “Free men cannot start a war,” he replies. “But once it is started, they can fight on in defeat. Herd men, followers of a leader, they cannot do that.” As Orden and Dr. Winter, the town physician and historian, face the threat of a firing squad in the final scene, they hear the echoes of dynamite in the distance, and Winter prophesies to their enemy, “The flies have conquered the flypaper.”

Despite the initial criticism, The Moon Is Down resonated with readers, particularly in occupied Europe. In the summer of 1942 the text made its way to Sweden, where printers ran off several thousand Norwegian-language copies of the novella in thinly bound 7½-by-4½ softcover books bearing the title Natt uten mane (Night Without Moon). Borne east across the Norwegian border in clandestine rail shipments or by foot (the 1,000-mile border was nearly impossible for the Germans to patrol), the story was received with knowing recognition by Norwegian patriots. Given the unnamed country’s logistical importance, descriptions of the occupiers and allusions to the British bombing of the country and airdrops of explosives and other weapons, Norwegian resistance members may have thought they were reading nonfiction.

While the novella’s influence on the Norwegian resistance over the last three years of the war is impossible to quantify, its widescale illicit distribution manifestly boosted the morale of resistance fighters. “The novel was something we all felt, and there you found the explanation of a lot of things that inspired us to fight against those who had the power,” wrote one Norwegian reviewer shortly after Germany’s surrender in 1945. Another deemed it “the epic of the underground.” Steinbeck himself must have felt a measure of professional vindication in 1945 when the Norwegian monarch presented him the King Haakon VII Freedom Cross for outstanding wartime achievement.

The novella’s message resounded beyond Norway. In Denmark young bookseller Morgens Staffeldt, outraged at his nation’s quick capitulation, engaged in resistance activities from the outset of the occupation. Returning to Copenhagen from his honeymoon in 1942, he brought with him The Moon Is Down, of which he printed 15,000 translated copies out of his ground-floor bookshop. (Occupying the floors above him was, of all things, a Gestapo office.) Other Danish resistance members distributed excerpts from the novella that echoed their Nazi-aligned government’s stance toward the occupiers, drawing a parallel between Steinbeck’s fictional but loathed collaborationists and their own leaders. The book doubtless encouraged members of Denmark’s small but determined resistance movement. Sabotage incidents, which numbered a mere 14 in January 1943, rose to 198 by that August. Among the saboteurs was Staffeldt, who was arrested in February 1944 after the Gestapo learned of his illicit activities.

After enduring weeks of interrogation, he was sent to a concentration camp and slated for execution. He managed to escape and make his way back to Copenhagen, where he and fellow saboteurs hid from the Germans. That fall, in a scene that could have been pulled from The Moon Is Down, Staffeldt and cohorts hid beneath crates of herring in a cargo boat as resistance agents whisked them to safety in Sweden.

Finally, in France, where commandos of Britain’s Special Operations Executive had been aiding resistance fighters since 1941, the novella resonated for its accurate portrayal of the fight against the Germans. First published in Switzerland and smuggled into France in 1943, Nuits sans lune (Moonless Nights) had been heavily censored by authorities in neutral Zurich. Gone, for example, were references to Britain, as well as the occupation of Belgium by the invaders amid a war two decades earlier. But in early 1944—in a twist reminiscent of the novella’s nod to female resistance fighters—a French bookbinder named Yvonne Paraf (nom de guerre Desvignes) undertook a new translation of the novella, one that left no doubt regarding the story’s World War II setting and German occupation.

Ironically, in a move to counter American propaganda as Allied armies threatened to break out of the Normandy hedgerows, the Germans released translated copies of Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath to point out social injustices in the United States. The French saw through the attempt, and together with other books in a vibrant underground canon, Paraf’s translation of The Moon Is Down helped inspire the resistance in the crucial year of 1944. In the novella one of the main efforts undertaken by the townspeople is to use air-dropped British dynamite to destroy railway infrastructure. The French had learned this arguably better than any other occupied nation. Between April and May 1944, just weeks after the release of Paraf’s translation of the novella, French resistance fighters destroyed some 1,800 locomotives and 6,000 railway cars, paving the way for the D-Day invasions.

Teachers in high school literature classes nationwide continue to assign students The Moon Is Down alongside such homegrown Steinbeck classics as The Grapes of Wrath and Of Mice and Men. In the decades since World War II the novella has been published in 92 editions worldwide.

Its enduring appeal shouldn’t come as a surprise. Steinbeck’s themes regarding the endurance of democratic ideals and resistance in the face of repression resonate to the present. “It is probably best described as a work of literature that served as propaganda,” critic Donald Coers wrote in the introduction to a 1995 edition of the book. The Moon Is Down continues to bear testament to the struggle for freedom of millions of people during World War II, as well as ongoing worldwide struggles against authoritarianism and neofasciscm. MH

Virginia-based freelancer Adam Nettina specializes in World War II and the Spanish Civil War. For further reading he recommends The Moon Is Down and Bombs Away: The Story of a Bomber Team, by John Steinbeck; John Steinbeck Goes to War, by Donald V. Coers; Hitler’s Pre-Emptive War, by Henrik O. Lund; and Wild Bill Donovan, by Douglas Waller.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Military History. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook.