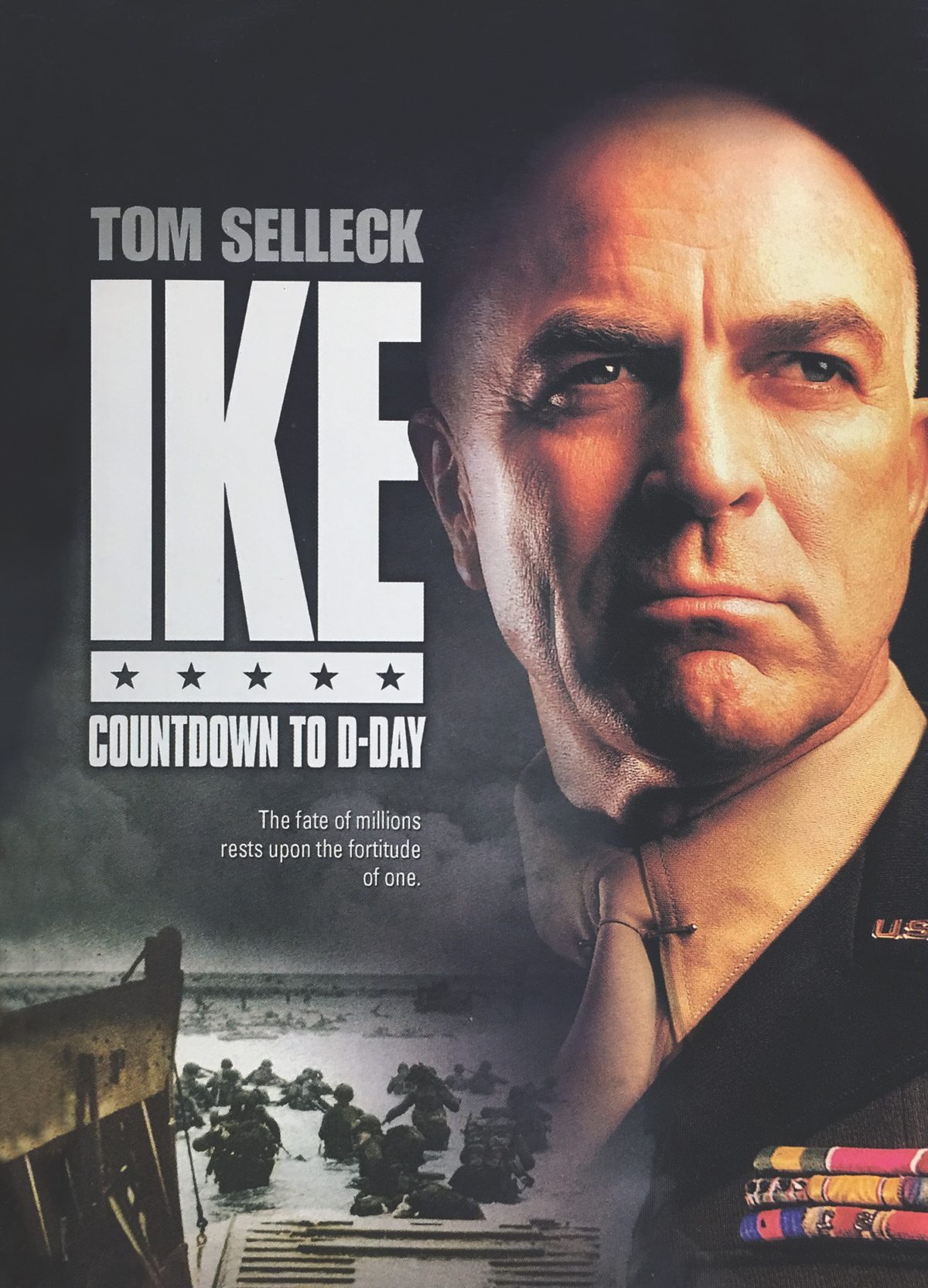

Directed by Robert Harmon and starring Tom Selleck in the title role, the 2004 made-for-TV film Ike: Countdown to D-Day reminds me that life presents us two kinds of choices: complex yet easy, and simple but hard.

The former is composed of numerous variables that might take considerable time to solve. Once these issues are resolved, however, the decision itself will become obvious. The second involves being tugged between two stark options. A few days before my father’s death from cancer, for example, his oncologist gave him a choice about whether or not to get a blood transfusion. It remains shocking to directly speak of death in our society, and she phrased it too delicately for my father to understand. Bewildered, he turned to me.

“Dad,” I said, “you’re going to die. If you get the transfusion, you’ll live a day or two longer, but you will die in more pain. If you don’t, you will die sooner but in less pain.” He asked me what to do. “I would get the transfusion,” I responded without a trace of emotion. “It will give you time to say goodbye to those you love.”

Everyone present, including the oncologist, was vaguely aghast, although my father was so addled on morphine that only the bluntest explanation, bereft of pathos, would have gotten through. I remember thinking of Admiral Ernest J. King, who served as U.S. chief of naval operations during World War II. He is said to have once remarked, “When the going gets tough, they call for the sons of bitches.” In my family, I was the designated son of a bitch.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower was, in his own way and on an incomparably greater scale, a designated son of a bitch. We seldom think of him that way, whereas the phrase springs readily to mind with regard to General George S. Patton or Ernie King—so stern he was once characterized as someone who “shaves every morning with a blowtorch.” Not Ike, whose affable manner and famous grin made him seem like everyone’s favorite uncle. True, Eisenhower had unmatched people skills, which helped make him an unparalleled military diplomat. But his main gift was the ability to make the simple, hard choices—an insight that lies at the heart of Ike: Countdown to D-Day.

The film dispenses with the illusion of an amiable Ike right away, opening with a close-up shot of the general exhaling smoke from one of his ubiquitous cigarettes and speaking to someone offscreen in a slow, testy voice: “Let me put it another way,” he emphasizes. “If I am not given complete and unfettered command of this situation, you can, if I may put it politely, sir, take this job and shove it where you choose because I’ll have damn well quit.” It’s December 1943, and the “situation” in question is the D-Day invasion, of which Ike demands supreme command. The “someone” offscreen turns out to be Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who spars with Eisenhower in his office about the arrogance of demanding such power while ultimately agreeing that there must be, as Ike insists, “one conductor of the orchestra.”

As the film progresses through 1944, we witness hundreds of staff officers at Eisenhower’s headquarters hard at work on invasion planning details. A key “complex yet easy” problem hinges on whether Normandy’s beaches will support the weight of a tank. (The data says it will, reassures General Omar Bradley.) An agonizing “simple but hard” choice concerns the deployment of 30,000 airborne troops. Eisenhower is told that if dropped immediately behind German beach defenses, 70 percent may become casualties. Eisenhower hopes this estimate is extreme, but it doesn’t matter if not; it is vital to give the seaborne troops a chance to gain a secure toehold. Everything depends on that—and 21,000 dead, wounded, or captured paratroopers is not too high a price to pay. When Eisenhower makes his famous visit to members of the 101st Airborne Division in the hours before their jump—one of the few times Selleck portrays his character as relaxed and avuncular—the audience realizes that D-Day’s supreme commander believes he is sending most of them to their deaths.

The film’s most pivotal “simple yet hard” choice, however, is the stark “go-no-go” decision of whether to launch the D-Day invasion itself. Eisenhower receives assurances that the weather during the mission’s best window—June 5-6, 1944—will be mild. It isn’t, and a storm rushing across the North Atlantic wrecks the chance of a June 5 invasion. A Royal Air Force meteorologist then forecasts a 24-hour lull in which the landings stand a strong chance of success. That’s good news, but only an educated guess. A fallback option is available in mid-July, but with no promise that conditions will be better. “I’m quite positive the order must be given,” Ike says quietly, firmly, and without a trace of drama. The simple, hard choices need no drama.