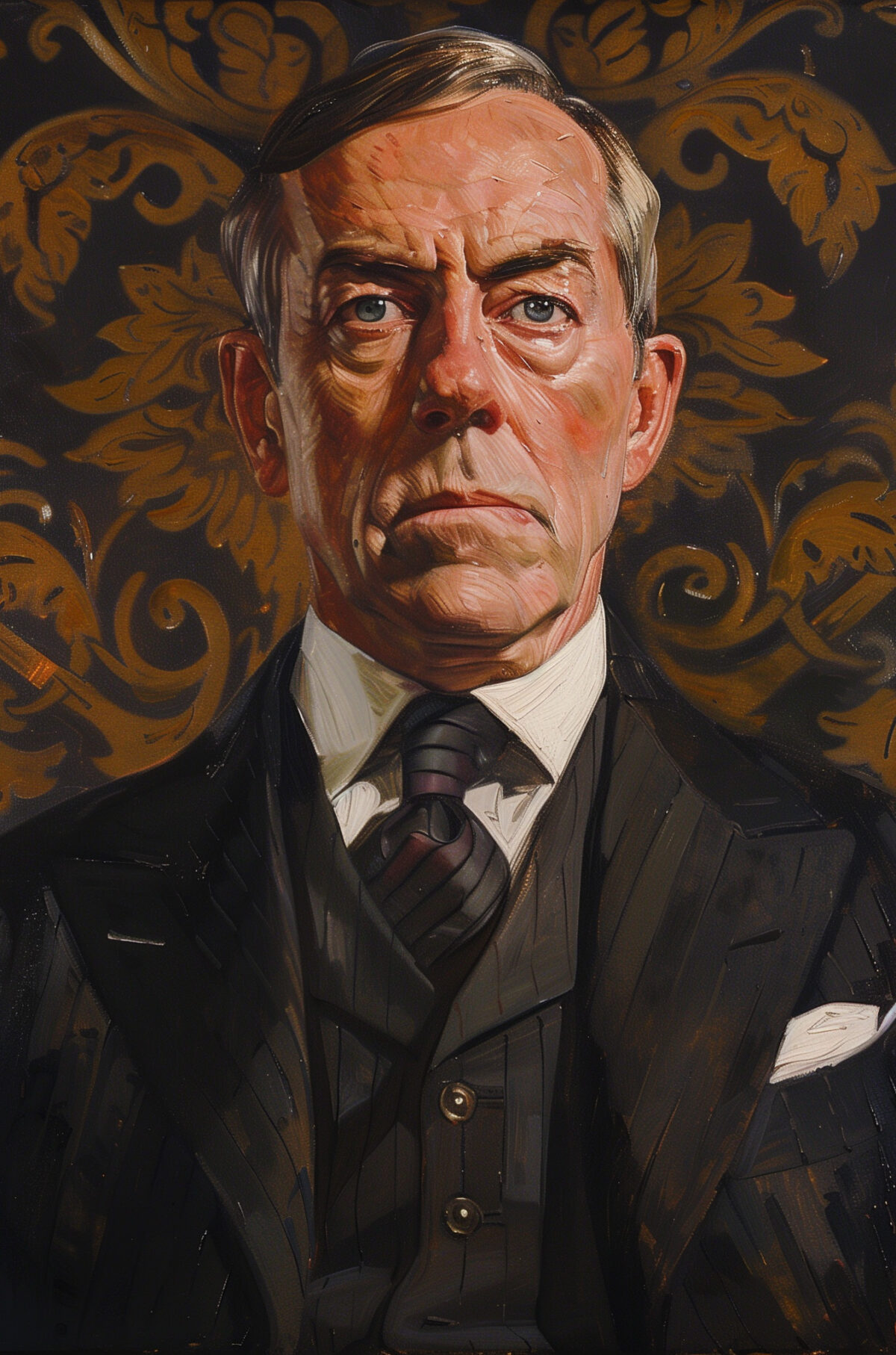

A chorus of conservative pundits portray Wilson as the man at the helm when everything began to go wrong for America

The Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist George Will made a startling assertion when he took the podium last year at a banquet sponsored by the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C. “I firmly believe that the most important decision taken anywhere in the 20th century was where to locate the Princeton graduate college,” Will declared.

The university’s president, Woodrow Wilson, then a high-minded political scientist who’d yet to run for public office, insisted that the new residential college be integrated into the main campus. But after a lengthy and bitter academic feud, in 1910 the university’s trustees and donors sided with the graduate school dean, who chose a more secluded location adjoining a golf course.

“When Wilson lost,” Will told the black-tie crowd, “he had one of his characteristic tantrums, went into politics and ruined the 20th century.”

The audience chortled and applauded, but Will was only half-joking. Wilson left Princeton for a new career as a crusading politician, and after soaring to national prominence during a short stint as Democratic governor of New Jersey, in 1912 he became the only scholar with a Ph.D. ever elected president of the United States. In his first term he pushed through a flurry of Progressive Era economic and regulatory reforms, and during the second he was hailed abroad as “the savior of humanity” after America and its allies had won World War I. Wilson remains a top-10 perennial on historians’ lists of outstanding presidents. But as the centennial of his ascension to the White House nears, he has also become a target for an increasingly raucous chorus of conservative pundits who portray him as the man at the helm when everything began to go wrong in America.

Will whimsically refers to Wilson as “The Root Of Much Mischief.” Others are less subtle or circumspect. They blame Wilson for things he did, like creating the FederalThe Pulitzer Prize–winning columnist George Will made a startling assertion when he took the podium last year at a banquet sponsored by the Cato Institute, the libertarian think tank in Washington, D.C. “I firmly believe that the most important decision taken anywhere in the 20th century was where to locate the Princeton graduate college,” Will declared.

The university’s president, Woodrow Wilson, then a high-minded political scientist who’d yet to run for public office, insisted that the new residential college be integrated into the main campus. But after a lengthy and bitter academic feud, in 1910 the university’s trustees and donors sided with the graduate school dean, who chose a more secluded location adjoining a golf course.

“When Wilson lost,” Will told the black-tie crowd, “he had one of his characteristic tantrums, went into politics and ruined the 20th century.”

The audience chortled and applauded, but Will was only half-joking. Wilson left Princeton for a new career as a crusading politician, and after soaring to national prominence during a short stint as Democratic governor of New Jersey, in 1912 he became the only scholar with a Ph.D. ever elected president of the United States. In his first term he pushed through a flurry of Progressive Era economic and regulatory reforms, and during the second he was hailed abroad as “the savior of humanity” after America and its allies had won World War I. Wilson remains a top-10 perennial on historians’ lists of outstanding presidents. But as the centennial of his ascension to the White House nears, he has also become a target for an increasingly raucous chorus of conservative pundits who portray him as the man at the helm when everything began to go wrong in America.

Will whimsically refers to Wilson as “The Root Of Much Mischief.” Others are less subtle or circumspect. They blame Wilson for things he did, like creating the Federal Reserve System and implementing a progressive income tax, and for things he didn’t do, like supporting eugenics or causing World War II. “The 20th Century’s first fascist dictator,” National Review columnist and Fox News contributor Jonah Goldberg called Wilson in his book Liberal Fascism. To tearily dramatic radio talk show host Glenn Beck, Wilson has become nothing less than the source of all political evil. “This is the architect that destroyed our faith, he destroyed our Constitution and he destroyed our founders, OK?” Beck ranted on the air last spring. “He started it!”

Nor is Wilson generating much praise from liberals who might be expected to defend him. Wilson was a bigot who sanctioned official segregation in Washington, D.C., say critics on the left. He used America’s entry into World War I as a rationale for crushing civil liberties. He was autocratic.

Such assaults on an intensely cerebral president, to whom many contemporary Americans have given scant thought since memorizing “League of Nations” for their history SATs, may reflect our ongoing jousting about the proper role of government—a question that intrigued Wilson himself since his graduate school days. They also reflect the fact that another Democrat with an ambitious first-term agenda now occupies the White House. If culture wars can rage over museum exhibits, Christmas and nutritional advice, why not over the 28th president of the United States?

“He was what we’d call today a polarizing figure,” says Barksdale Maynard, a Wilson biographer prone to scholarly understatement.

From the bay window of the Princeton president’s office in 1879 Hall, Maynard points out during a walking tour of the university’s spired campus, Wilson could gaze directly down Prospect Avenue at the row of eating clubs he despised and tried in vain to vanquish. It must have been a galling view. Alumni had built these sprawling brick and stone mansions, and the groups had grown so socially important by the turn of the 20th century that hopeful preppies sometimes focused their campus visits on Tiger Inn or the Ivy Club, ignoring the adjacent university where they were supposed to be educated. “Wilson regarded these clubs as antithetical to what he was trying to build at Princeton,” says Maynard. “It was the son of a Presbyterian minister from the South confronting the New York aristocrats.”

So why wouldn’t today’s conservative populists, Tea Party supporters for instance, like Thomas Woodrow Wilson? A God-fearing lifelong churchgoer, he was the son, grandson and nephew of Presbyterian clergy. Never wealthy, he only rented the unpretentious Tudor house, a short walk from the campus, where he lived as governor of New Jersey and where he received the telegram announcing he’d won the presidency. “It’s not Mount Vernon,” Maynard notes dryly.

But that hardly seems to matter.

The Wilson bashing has been stoked in part by conservative academics who have trolled through his papers, copies of which occupy hundreds of acid-free boxes in the rare manuscript library nearby. Scholars and graduate students labored over this enormous project for decades (they had to decipher the old-fashioned shorthand Wilson once favored); the 69th and final volume of papers came off the press in 1994.

Political scientist Ronald Pestritto, whose 2005 book Woodrow Wilson and the Roots of Modern Liberalism drew on that material, used scholarly language but lobbed serious accusations, charging, for instance, that Wilson’s leadership “is not as democratic as it seems, but instead amounts to elite governance under a veneer of democratic rhetoric.” Such ideas soon began cropping up in more popular writing, like Jonah Goldberg’s 2007 book, which describes Wilson as an imperialist, totalitarian warmonger who, from his youth, was “infatuated with political power” and then corrupted by it.

Glenn Beck read Pestritto’s book at the recommendation of political philosopher Robert George, who now holds the chair created for Wilson at Princeton and is among his gentler conservative critics. But there’s nothing gentle about the way Beck has vilified Wilson in his best-selling books, on a syndicated radio broadcast that reaches an estimated 10 million listeners a week, and on a daily Fox News television show that the network recently pulled the plug on. He blasts Wilson as an “S.O.B.,” charges that he “perverted Christianity” and ranks him No. 1 on his “Top Ten Bastards of All Time” lists—ahead of not only both Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, but also Pontius Pilate, Hitler and Pol Pot.

Even the conservative Weekly Standard scolded Beck last year, declaring, “This is nonsense. Whatever you think of Theodore Roosevelt, he was not Lenin. Woodrow Wilson was not Stalin.” That hasn’t slowed Beck’s assault. He consoles himself, he has said, by looking up from his desk at a treasured gift: a framed front page of a 1924 newspaper headlined, “Woodrow Wilson Is Dead.”

Many presidents’ standings wax and wane over the decades, of course. “I don’t think any statesman can sleep soundly in his grave,” says Robert George. But rarely has a debate about a historic figure’s accomplishments and shortcomings turned so vitriolic. So whence this wave of animosity? It starts with the progressive movement that helped elect Wilson and that also can claim Theodore Roosevelt. “In a nutshell, the argument is that this marked the first era in American history where prominent national leaders were openly critical of the Constitution,” Pestritto explains.

The criticism can sound fairly innocuous: Reformers like Wilson contended that a system of government established in the late 1700s for a smaller, sparsely populated country had become inadequate in a world of industrialization, immigration, international tensions and other developments the founders couldn’t have foreseen. Government therefore had to adapt.

“The Constitution was not meant to hold the government back to the time of horses and wagons,” Wilson wrote in his scholarly tome Constitutional Government in the United States (1908). He deplored the way the branches of government checkmated each other to stall progress—or what he saw as progress—and admired the British parliamentary system as more efficient.

The problem, in the conservative critique, is what results. In George Will’s words: “Concentrate as much power as possible in Washington, concentrate as much Washington power as possible in the executive branch and concentrate enough experts in the executive branch” to administer a much larger government. And it was Wilson, adds Robert George, who made progressivism “a doctrine, not just a sensibility. He’s the guy who laid out the justifications and ideas.”

Perhaps, though, it’s less Wilson’s ideas that trouble his critics than what he managed to do with them, especially in his first term as president. “His greatest domestic achievement was the creation of the Federal Reserve System, and that’s probably enough for Glenn Beck in itself,” says Thomas J. Knock, a historian at Southern Methodist University and another Wilson biographer. But the list goes on: The Federal Trade Commission. The Clayton Antitrust Act. The first downward revision of the tariff and the implementation of the progressive income tax (though the 16th Amendment was actually passed and ratified just before Wilson took office). The first federal law establishing an eight-hour day (for railroad workers). The first federal law restricting child labor (later struck down by the Supreme Court). The appointment of Justice Louis Brandeis, the first Jew to serve on the Supreme Court.

Wilson’s second term was another matter. He couldn’t live up to the campaign slogan “He kept us out of war,” of course, and some supporters never forgave him for America’s immersion in the mechanized horrors of World War I. Nor did he succeed in engineering American participation in his cherished League of Nations, though he—literally—nearly died from the physical stress he experienced trying. But his blazing domestic record includes actions some conservatives condemn to this day.

“If those on the right want to blame him, put him in the pantheon, the Hall of Shame for people who expanded the state and made it more interventionist, especially in the economy, fair enough,” says University of Wisconsin historian John Milton Cooper, author of several Wilson biographies. “He belongs there.”

The thing is, he’s got plenty of company.

Why not turn, for a presidential piñata, to Theodore Roosevelt, who was ramming through progressive legislation before Wilson ever entered politics? In the 1912 election, each vied to portray himself as the greater advocate of strong government. Why not lambaste Franklin Roosevelt, whom Wilson appointed to his first national post, assistant secretary of the navy? Surely FDR’s New Deal proved at least as threatening, to those with a taste for limited government, as Wilson’s New Freedom agenda.

One could argue that talk radio hosts have a penchant for discovering and trumpeting supposed hidden truths, revealing to their listeners what high school textbooks, college curricula and the media (all, in this scenario, controlled by conniving liberals) have concealed. Attacking FDR is way too obvious; everyone knows he steered the nation leftwards. Wilson’s role as the alleged destroyer of the Constitution makes for more piquant programming. Or perhaps Wilson’s academic background, seen as an asset at the time, brands him a member of the Eastern elite, despite his middle-class Southern upbringing. He was the ultimate pointy-headed intellectual; editorial cartoonists delighted in portraying him in a cap and gown.

Or one could theorize, as John Milton Cooper does, that there’s a simpler explanation: Americans just don’t cotton to Woodrow Wilson. That it’s unpatriotic or dangerous to criticize the Constitution strikes Cooper as a nonsensical argument—what are all those amendments for if the founders were so unerring? But he has noticed that among the presidents who top historians’ lists, “sooner or later you get the glow of universal acceptance and acclaim.” To his sorrow, “that has never happened to Wilson.”

Case in point: Theodore Roosevelt. Given the passage of a full century, plus a little selective memory, liberals can applaud the progressive trustbuster and conservatives the rugged Rough Rider. “TR tends to enjoy a certain above-the-battle reputation,” Cooper says. “People just don’t want to go after him.”

Even FDR, hardly beloved by conservatives, got plenty of laudatory press during the 1982 centennial of his birth, Cooper points out. Roosevelt fought the unambiguous Good War, after all, and saw the nation through the Depression; meanwhile, millions of Americans continue to rely on the social safety net he constructed.

But Wilson seems fair game. “He rubs people the wrong way, for some reason,” Thomas Knock concurs. In historic reputations, as in contemporary political polls, personalities matter. Theodore Roosevelt so often looks, in his grinning photographs, like he’s having a ripping good time. Wilson, with his long face and severe pince-nez glasses, looks like he’s headed for a dental appointment. Roosevelt once referred to him, in fact, as resembling “the apothecary’s clerk.”

The distaste extends to those on the left who would normally be Wilson’s allies and defenders—this was a man once endorsed by legendary labor organizer Mother Jones and civil rights activist W.E.B. Du Bois, no less—primarily for two reasons. First, he held typically unenlightened views on race. Born in Virginia and raised in Georgia, he paid little attention to blacks’ legal or economic plight. As Princeton’s president, he refused to consider admitting black students at a time when Ivy League rivals Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania had begun to accept them.

Later, as a president who gave considerable autonomy to his Cabinet members, many of them fellow Southerners, he acquiesced as they set about segregating the Postal Service, the Treasury Department and the Bureau of Printing and Engraving; during Wilson’s administration the number of black government employees actually declined. He also permitted a gala White House screening of D.W. Griffith’s hateful epic The Birth of a Nation, apparently as a favor to someone he had briefly attended school with; though he later tried to disassociate himself, the incident outraged the protesting NAACP.

Black leaders subsequently declined to support his reelection. “We need scarcely to say that you have grievously disappointed us,” Du Bois wrote.

“By any reasonable standards anyone would apply today, I think it’s fair to say Woodrow Wilson was a racist,” Cooper acknowledges, regretfully.

That other presidents also qualify doesn’t shield Wilson from contemporary scorn. Middletown, Conn.—where Wilson once taught at Wesleyan University—named a public school in his honor in 1931, but in 2004, two high school seniors argued (ultimately unsuccessfully) that the town shouldn’t honor a bigot. “The question I’m asked the most when I talk about Wilson, almost always by some young person in the audience, is ‘What about his racism?’ ” says Barksdale Maynard. “It’s poisoning his reputation.”

Wilson’s reputation also suffers from the Sedition Act and the Espionage Act, laws he supported and signed in his second term, convinced that winning World War I required a crackdown on home-front dissent. Overriding the pleas of onetime supporters, he permitted a variety of transgressions against civil liberties, leading to about 2,000 wartime prosecutions. His postmaster general banned the mailing of a variety of liberal, socialist and radical publications. His Justice Department rounded up and arrested labor organizers. Vigilantes attacked innocent people for the crime of being German-American. The socialist leader Eugene Debs, who’d run against him in the four-way election of 1912, was tried and sentenced to 10 years for making antiwar speeches.

Wilson remained publicly silent about all of it and refused to pardon the aging, ailing Debs, even after the armistice. “Wilson was a typical Puritan,” H.L. Mencken wrote in 1921. “Magnanimity was simply beyond him.”

In a heated 2008 essay that branded Wilson “an intolerant demagogue,” Harper’s publisher John R. McArthur concluded, “The great proponent of democracy engaged in the most anti-democratic domestic crusade in American history.” A century earlier, Harper’s Weekly had helped propel Wilson into politics; now, disdain for Wilson may be the sole issue on which its publisher agrees with Glenn Beck.

In a way, this ongoing tussle over history’s verdict is old news for Wilson. Historians still credit him with presiding over America’s entrance onto the international stage, and his stock was high when the Allies won the war. But the peace talks in Paris in 1919 turned fractious and punitive, and afterwards Wilson was unable to coax or pummel a Republican-controlled Senate into approving the Treaty of Versailles and, with it, American membership in the League of Nations. A barnstorming cross-country speaking tour, an attempt to sell the Senate on the treaty by selling the public, possibly brought on the stroke that crippled and eventually killed him, and left the country rudderless for the crucial 15 months remaining in his term. Wilson departed the White House a diminished and discredited leader.

Yet his star rose again during World War II, by which time an international organization that could have defused conflicts didn’t sound like such a terrible idea. Journalists and biographers took renewed interest, and Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck spent a then unprecedented $5 million to film a Technicolor extravaganza simply titled Wilson, portraying him as a man ahead of his time. Released in 1944, it was nominated for 10 Academy Awards.

In another 20 years, therefore, bloggers and editorialists may be quoting admiringly from Wilson’s weighty Constitutional Government in American Politics and rattling on about the ambitious Fourteen Points peace plan he laid out for Congress at the end of World War I.

What if Wilson had had access to some of the political artillery his successors have wielded? He was a spellbinding orator, and if he’d been able to address the nation using the newfangled medium called radio, he might have been able to cajole America into League membership. At least he might have avoided the exhausting trek by train that sapped him and likely brought on his stroke. But his first and only radio talk, marking the fifth anniversary of the World War I armistice, came in 1923, after he’d left office.

His admirers like to kick around these counterfactual versions of history. What if the stroke had killed him quickly? “He would have been a martyr instead of an ineffectual political ghost, and that might have carried America into the League,” Knock conjectures.

For that matter, what if Wilson had lost the 1916 election, instead of barely squeaking back into office? His first-term accomplishments untarnished by having led the country into war and then into an ugly peace, and by his long, slow fade, he might now be recalled with greater warmth.

Well, who knows? But as the current flap raises his profile again, it appears to have produced certain beneficiaries. Every past president, after all, generates a small industry. Once Beck started mentioning Ronald Pestritto’s book, for instance, “paperback sales really shot through the roof,” at least by academic standards, the pleased author says. At the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum in Staunton, Va., where Wilson was born in a handsome brick house on a hill, visitorship has grown 12 percent in the past year.

In Washington, D.C., the Woodrow Wilson House, the Georgian Revival home where Wilson lived after leaving office and where he died, is prospering, too. “We’ve been doing very well for the last few years,” says its director.

“You know, no controversy is entirely bad.”

Paula Span, a former Washington Post reporter, teaches at the Columbia University School of Journalism and blogs for the New York Times.