One of the side benefits of the Soviet Union’s disintegration was that historians and filmmakers were at last able to travel behind the former Iron Curtain and record honest interviews with people involved in World War II. I was one of the first to crisscross the newly liberated Baltic States and Ukraine during the 1990s in search of this testimony, and heard much that was surprising and shocking. But the encounter that has stayed with me most profoundly was with an elderly Lithuanian peasant farmer called Petras Zelionka.

One of the side benefits of the Soviet Union’s disintegration was that historians and filmmakers were at last able to travel behind the former Iron Curtain and record honest interviews with people involved in World War II. I was one of the first to crisscross the newly liberated Baltic States and Ukraine during the 1990s in search of this testimony, and heard much that was surprising and shocking. But the encounter that has stayed with me most profoundly was with an elderly Lithuanian peasant farmer called Petras Zelionka.

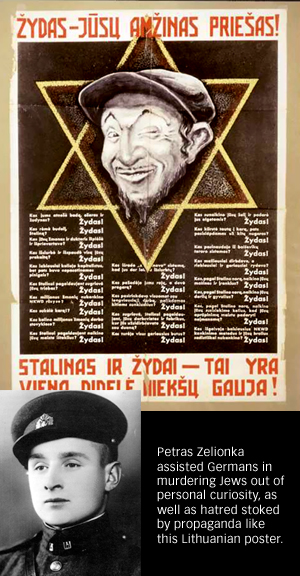

Zelionka looked like any other pensioner. But years before, during the summer of 1941, he had been a mass murderer. As a member of a Lithuanian army unit, he had helped the Germans shoot Jewish men, women, and children in the region around Kaunas, Lithuania’s second-largest city.

“We took them from the ghetto into some forest,” he told me. “In that forest they were shot: men, women, and everyone at the same time. It was our battalion and a German detachment. You could not do it without the Germans. They had machine guns. We had just to shoot, go back to the cars and go away. You just pressed the trigger and shot. And that was it. It was not a big ceremony. Everything short and clear. Without any ceremonies—nothing. We would shoot them, give them up for lost, and that was it. At the edge of the grave, some of them used to say, ‘Long live Stalin!’ Only that kind of ‘prank.’”

Many Lithuanians, like many Nazis, bought into the fantasy that Communism and Judaism were inextricably linked. Their hatred for both fueled the desire to kill. So did greed. The German security forces “used to bring us vodka; we could drink as much as we wanted. If they give me, I drink…. Everyone is braver then…. They used to search [the Jews] and take all golden things from them. Watches, et cetera—everything made of gold. Our former warrant officer also had a suitcase where he used to put these things.”

I was astonished that Zelionka was so matter-of-fact about his part in one of history’s most horrendous atrocities—in particular, about participating in the murder of children. I had already heard heart-rending testimony from bystanders who had witnessed small children clinging to their dead mothers, screaming in torment in the final moments before they too were shot. How could Zelionka and his comrades have killed children? “This is a tragedy, a big tragedy,” he ans-wered. “How should I put it to you? How can I explain? It’s a kind of curiosity. You just pull the trigger, he falls, and that’s it. Some people are doomed, and that’s it.”

I don’t believe Zelionka really thought the murder of Jews was a “big tragedy.” I think he was a violent anti-Semite of the most committed kind. But I do think he was being honest when he said his ability to kill was fueled in part by a “kind of curiosity.” Indeed, Zelionka’s testimony reminds us that curiosity can become a dark motivating force in some lives.

Zelionka was most certainly not sorry for what he had done. After serving 20 years in a gulag for his crime, he thought he had paid the necessary price—one imposed on him by the victors in the war. More disturbing was that 50 years later this mass murderer appeared to still think he had done the “right thing” in the summer of 1941. Just like Adolf Hitler, Petras Zelionka would go to his grave believing that he had simply been misunderstood.