Only when settlers instituted private property rights did the New World thrive

Americans have long enshrined individualism. Colonial experiments helped shape that perspective by illustrating in practical terms the flaws of social collectivism. The colonies of Virginia, Massachusetts, and Georgia are examples.

In 1605, King James I licensed two groups of merchants operating as The London (Virginia) Company to establish a profit-making colony in North America. The colony was to take form north of Spanish-controlled Florida in a mid-Atlantic region Britain had named Virginia in honor of Queen Elizabeth I. According to the charter, Virginia’s colonists were to spread Christianity, bring “the infidel and savage, living in those parts, to human civility,” and enrich the sponsoring company by seeking and finding “all manner of mines of gold, silver, and copper.” The London Company claimed all the colony’s land and all its profits. Whatever colonists might produce was to go into the common stores, in the main a company holding.

Few would-be colonists could afford an ocean passage and the cost of starting a new life. In England, a law known as the Statute of Artificers required adults under age 60 with no skilled trade to indenture themselves—that is, agree to a period of service at no pay but receiving room and board—to anyone demanding their labor. More than half the original Virginia complement signed indenture contracts, agreeing to work off their passage, residence, and board by toiling for the company as long as seven years. An indentured servant completing his contract stood to receive freedom dues, a settlement that could include the use of 50 acres or so of land. But that was stewardship, not ownership. The company perpetually controlled the property’s use and granted no inheritance rights. Some Virginia indentures were only 13 years old. Others were ambitious young gentlemen, like Captain John Smith, a former mercenary. Few had practical experience at the activities required to establish a community. The London Company described its initial roster of colonizers as “unruly gallants, criminals, and loafers.”

In December 1606, the ships Susan Constant, Discovery, and Godspeed set sail from London carrying as passengers 105 men and boys chosen by the company to make the Virginia colony a reality. After nearly five months at sea, the ships sailed into a large bay about 35 miles up a river. On May 14, 1607, after forming a governing council whose members included Smith and expedition commander Christopher Newport, the group landed on a peninsula in the river and erected a cross to claim the region in the name of King James I. The colonists called their putative settlement Jamestown and named the river the James. As a starting place, the peninsula seemed ideal: easily defended, with lines of sight to watch for approaching vessels or strangers on foot. According to colonist and diarist George Percy the spit and adjoining land had “faire meadows,” abundant game, “good and fruitful soil,” and stands of nut trees as well as wild strawberries, raspberries, and other unfamiliar fruits. The Powhatan, an Indian tribe whose chief’s name was also Powhatan, seemed friendly. “Heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation,” Smith wrote later.

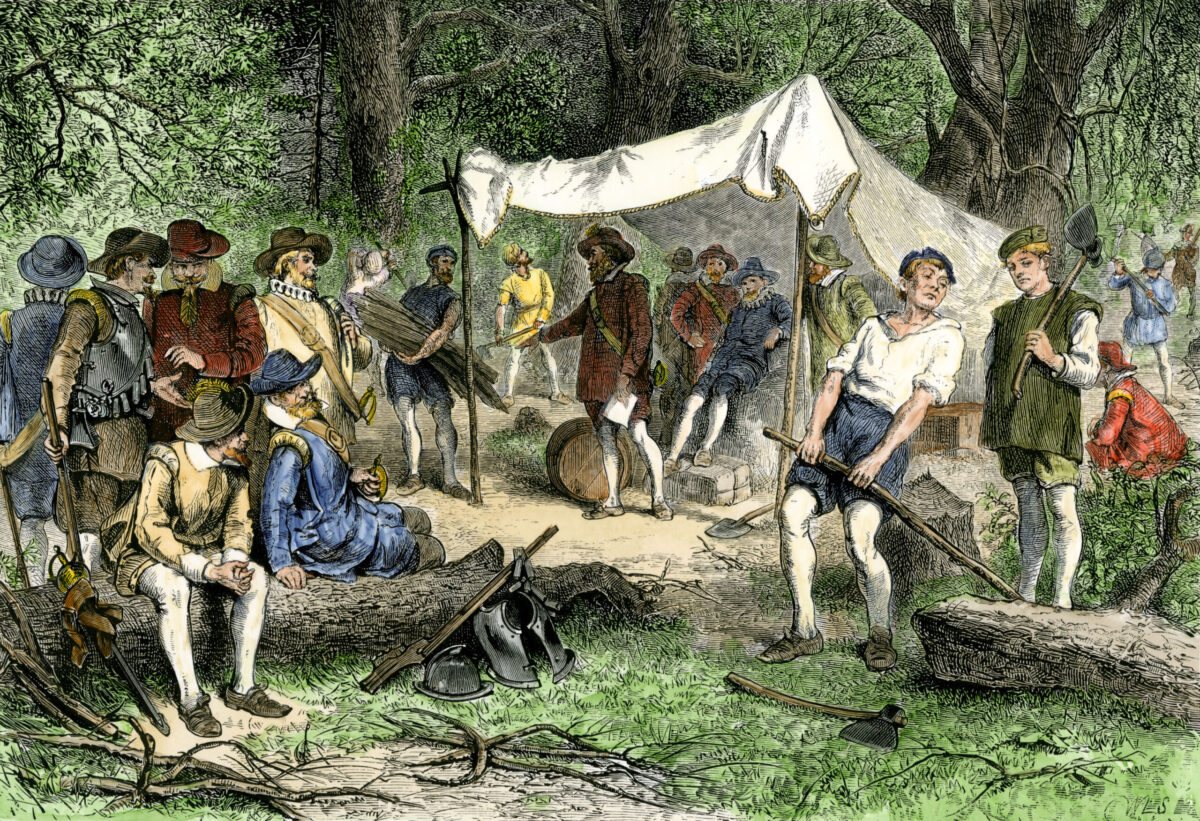

The newcomers felled trees and set to building a triangular log fort. Within two weeks, however, Powhatan and his warriors were besieging the immigrants. The Indians wounded 11 Englishmen, killing two—the start of a campaign of harassment that kept the colonists from foraging for food and planting crops. Summer’s arrival made clear that the peninsula lacked potable water, and that nearby lowlands were thick with mosquitoes whose bite brought on a debilitating fever. And without knowing it, the expedition had arrived during what may have been the mid-Atlantic’s worst dry spell in eight centuries.

Nature and inertia were working against the Virginia colony, as was the enterprise’s organizing principle. Having no stake in their efforts, most indentures and free men lapsed into indolence and fell to bickering. A fifth of the party’s members did most of the work; the rest leeched off the common stores. By mid-June, Jamestowners had gotten only two small fields of grain growing. On June 22, the three supply ships left for England to fetch more goods and colonists. Summer passed in a malarial haze. The corn harvest was scant. Food ran short. Besides malaria, residents fell prey to pneumonia, dysentery, and malnutrition, as well as Indian attacks. In December the Powhatan took Smith prisoner. Huddling all winter in their tricornered bastion, settlers at Jamestown died at the rate of three or four a day. Survivors ate dogs, cats, rats, snakes, roots, boots, shoes—even going so far, colonist George Percy noted, “to digge up deade corpses out of graves and to eate them.” Percy, who kept a journal of what colonists called “the Starving Time,” wrote, “There was never Englishman left in a foreign country in such miserie as we were in that new discovered Virginia.”

The next spring only 38 settlers remained alive. Miraculously, Smith had survived, saved by the Indian chief’s daughter and embraced by the tribe. He persuaded the Indians to trade food to the colonists in exchange for glass beads, copper, and iron tools. That spring the tribe taught the newcomers how to forage in the forest and how to grow corn, yams, and other native crops.

In September the colonists elected Smith president. Reversing official policy, the former mercenary declared Virginia’s days of easy riding over. “He who will not work will not eat,” Smith declared. He forced slackers and layabouts to fell and lumber trees, erect buildings, work fields, and do whatever else was necessary to keep all the settlers alive. “A plain soldier that can use a pickaxe and spade,” he said, “is better than five knights.” In October 1608 a supply ship brought supplies and another 100 immigrants, including two women.

Smith’s tenure as president and its rigorous discipline began too late to have much effect on farming going into the winter of 1608-09, but that year’s meager crop, supplemented by provisions from home, saw the Jamestown settlers through with minimal suffering.

In June 1609, a nine-ship London Company fleet led by Venture, carrying new Virginia colonial governor Sir Thomas Gates, departed England with some 500 emigres, including 25 women and a number of children, on board. Halfway to America, a hurricane scattered the fleet. Venture wound up beached off Bermuda needing repairs. That work took many months, during which time the flagship’s sailors also built two smaller vessels. In August the other eight ships, low on stores and full of sick passengers and crewmen, docked at Jamestown. In three days the 350 starving newcomers consumed that season’s entire corn harvest. Malaise and fear gripped the crowded, filthy town. Smith’s rigorous leadership had united the colony, but some settlers resented him. A suspicious explosion badly injured the former mercenary, and in October, Smith departed aboard a supply ship for England, replaced as colony president by George Percy. Powhatan again began attacking; Indian raids went on all winter. At least some starving settlers resorted to what Percy called “those things which seem incredible”—cannibalism. When Venture finally arrived from Bermuda on May 10, 1610, that ship’s passengers, crew, and Governor Gates found Jamestown down to 100 souls, the town palisades in disrepair, the church in ruins, the houses empty, “rent up and burnt.” Survivors were “lamentable and behowlde,” so weakened they could barely rise. “We are starved!” they cried. “We are starved.”

Horrified, Gates decided to abandon the colony. Venture had sailed from Bermuda with the two smaller vessels build during the forced layover. Onto these craft and Venture the able helped the debilitated stagger aboard. On June 7, the ships sailed for England. At the confluence of the James and Chesapeake Bay, the little armada encountered three arriving ships. These vessels, also from the London Company, carried 150 colonists and plenty of provisions. All hands made for Jamestown, where the struggle to survive and to expand the colony resumed.

In May 1611, the latest Jamestown provisioning expedition delivered men, cattle, provisions, and lieutenant governor Sir Thomas Dale. A hard charger, Dale bristled at the sight of “idell” colonists, some using the fort’s streets for bowling. Dale cracked down, issuing prescriptive edicts. Dale’s Code: Lawes, Divine, Morall and Martial threatened death for desertion, embezzlement, stealing from the public stores, and other crimes. Percy described how Dale named parties “to be hanged, some burned, some to be broken upon wheeles, others to be staked, and some to be shot to deathe, all this extreme and cruewel torture he used and inflicted upon them to terrify the rest from attempteinge the lyke.”

Dale got Jamestown on a firmer footing but came to see that bullying and terror were not efficient tools for maintaining a community, breeding as they did reduced productivity, never mind resentment and talk of rebellion. The same was true of collective agriculture. Discarding collectivism, Dale assigned each adult male three acres of land; landholders were to work their parcels for themselves and their families. Embracing the idea of private property, stakeholders engaged in “gathering and reaping the fruit of their labor with much joy and comfort,” colonist John Rolf said. Food production blossomed. Jamestown thrived and became the first permanent colony in North America.

Fleeing religious persecution in Britain, the fundamentalist Pilgrims, after nesting temporarily in the Netherlands, contracted with a joint-stake company in England. The investors agreed to finance a settlement in Virginia provided the faithful indentured themselves for seven years, during which they could not own real estate or work for themselves. Except for a few personal belongings, everything else, including labor, belonged to the company. Revenues were to fund the necessities of life, each person receiving an equal share of whatever the group produced without regard to individual contribution. Profits would go to the company.

On September 6, 1620, Mayflower, with a crew of 30, departed Plymouth, England, carrying 102 Pilgrims. Adverse conditions and navigational errors drove the ship far off course to the north, near a peninsula extending from the mainland and curling to enclose a bay. Rather than risk icy seas and winter storms to try to reach Virginia, the Pilgrims decided to settle where they were, selecting a site on the bay in which their ship had anchored. Plimoth Plantation—named for the port across the Atlantic, as was the colony—had been a Patuxet Indian village until smallpox years before wiped out the native inhabitants. The vicinity had been cleared for planting and was dotted with caches of dried beans and corn.

The Pilgrims junked their contract with the joint-stake company and wrote a new contract among themselves. The Mayflower Compact is often described as America’s first example of self-government. Drafted by William Bradford and signed by 41 male passengers, the compact stated simply that for the good of the colony and to encourage better order and preservation, a “civill body politick” would enact “just & equall lawes, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and offices” as required. No democratic instrument, the Mayflower Compact reflected economic, philosophical, and religious thinking of the era and was based on the works of Plato, who believed in central planning in the context of communal priority.

The first winter was harsh. “In two or three months’ time, half their company had died, especially in January and February, being the depth of winter, and wanting houses and other comforts; being inflicted with scurvy and other disease which the long voyage and their inaccomodate condition had brought upon them,” Bradford wrote in his journal. “So as they died sometimes two or three a day during those months, that of the 100 odd persons from the Mayflower, scarcely fifty remained.”

Governor John Garner collapsed in the fields and died in April 1621. The colonists elected Bradford to replace him. Friendly Pokanoket Indians helped the colonists grow enough crops that summer to survive the winter, whose start all hands marked with a celebratory dinner.

The Plimoth colony’s elation proved premature. That year’s collectively managed growing season had shambled unproductively, with crops rotting in the ground, resources squandered, and the tragedy of the commons rampant, a prelude to another hungry winter. In spring 1622, Bradford and the colony’s council voted out collectivism in favor of private property. “The failure of that experiment of communal system, the taking away of private property, and the possession of it in community by commonwealth, was found to breed much confusion and discontent, and retard much employment which would have been to the general benefit,” Bradford wrote in his journal. “At length after much debate of things, I…gave way that they should eat corn every man for his own particular, and in this regard trust to themselves. And so assigned every family a parcel of land.” The dramatic change of heart at Plimoth Plantation, Bradford said, “had very good success, for it made all hands industrious, so as much corn was planted than otherwise would have been by any other means. . . Any general want or famine hath not been amongst them to this day.”

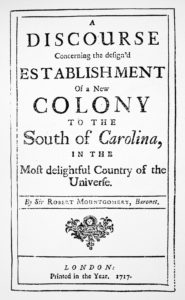

Subsequent American colonies generally adopted an individualist model. But beginning in 1717 a southern colony proposed to establish a bureaucratic collective that would govern every aspect of community life according to a plan concocted that year by William Montgomery, baronet of Skelmorlie. Montgomery, his family, and his friends had been planting colonies in the Western Hemisphere for a century. In June 1717 the lord proprietors of Carolina granted Montgomery a parcel of land between the Allatamaha and Savanna rivers upon which to establish a colony. Montgomery published the margravate of Azilia, a tract specifying in detail how the colony was to function and be governed, down to the siting of residences and farms. The overseer would live in the middle of the settlement so he could oversee every aspect of public and private life.

Montgomery died in 1731, his plans unrealized. The following year, Sir James Edward Oglethorpe, a British soldier, member of Parliament, and philanthropist, obtained a charter through his Bray Associates from King George II to establish in the New World a charitable colony for debtors and victims of religious persecution. The King granted the request on Oglethorpe’s promise that colonists would produce silk, capitalizing on a mulberry tree native to the region but similar to a species of tree in Asia upon whose leaves silkworms fed.

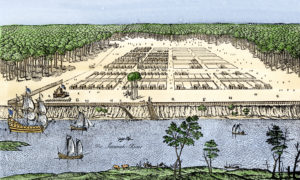

Georgia’s first British residents, led by Oglethorpe, landed in early 1733. The new arrivals established Savannah, a town that the trustees in Britain organized and governed almost precisely according to Montgomery’s plan. A rigid land control system limited parcels to 500 acres. Workers too poor to pay their way from England and who would be supported “on the charity” for a year received 50 acres. Individuals assigned parcels could not divide, sell, rent, trade, mortgage or will the land they worked. Thomas Causton, whom Oglethorpe chose as “storekeeper”—agent in charge of doling out provisions to the colony—said colonists “had neither land, rights or possessions, that the Trustees gave and that the Trustees could freely take away.” The colony banned alcohol and in detail prescribed how settlers were to live and work.

Georgians imported silkworms, set the caterpillars to feeding, and prepared to prosper. The worms, unable to live on American mulberry leaves, died, and with them perished hopes for profits on silk. Settlers began to flee. The system Montgomery had designed, with its onerous and minute regulations, disintegrated. By 1740, more than five-sixths of Georgia’s population was gone. “The poor inhabitants of Georgia,” a settler lamented, “are scattered over the face of the earth, her plantations a wild, her towns a desert, her villages in rubbish. . .her liberties a jest, an object of pity.”

Under intense pressure, the colony’s trustees began to loosen their control, beginning with economic planning. Starting in 1738, remaining settlers gradually were granted ownership of their property and its production. The colony scrapped most rules governing day-to-day life. Finally, in 1752, the trustees gave up entirely, surrendering their charter to the Crown. Georgia became a Royal Colony in 1754.

Now endowed with rights to production and ownership and the economic liberty to use them, Georgians began to experiment. Some farmers converted marshes into wild rice fields. Others planted cotton. Introduced in Georgia in 1734, that crop would revolutionize that colony and its economy and, especially after the introduction of the mechanical cotton gin in the early 19th century, other southern states as well. By 1775, Georgia’s prosperity had rebounded. The population was eight times what it had been under the old system. Imports were on the rise, as were exports of indigo, rice, sugar, cotton products, clay pottery and other goods. The overall effect was to transform Georgia into one of the more attractive English settlements.

In attempting initially to hold property and labor in common and on collective terms, Georgia, Massachusetts, and Virginia provided cautionary examples. Fettered by their governing systems, Jamestown and Plymouth lapsed into starvation and disease that were defeated only when residents took on individual responsibility. In Georgia, tight controls on life drove settlers away until colonists there obtained the liberty to control their economic destinies. Embracing individual autonomy helped English colonies in the New World survive, thrive, and become the basis for a new system of government.

This American History story was posted on Historynet.com on April 25, 2020.