“See here, Doc, if you’re goin’ to take that leg off, you’d better be about it—I’m comin’ to.”

Those were the frustrated and possibly fearful words of a wounded soldier in the aftermath of the July 1863 Battle of Honey Springs. The unidentified soldier was so grievously wounded that army surgeons had opted for amputation. Understandably, he was worried, particularly at the prospect of suffering such a painful operation without the aid of anesthesia. Much to his surprise, the patient was informed that “his leg was already off and the stump ‘done up in a rag,’” Raising himself a little on his elbows to verify the news, the soldier remarked, “Is that so? I didn’t know a thing about it.” Such was the miracle of anesthesia.

We have long been led to believe that surgeons used anesthetics only occasionally during the war, but that is untrue. In fact, anesthetics were an absolutely essential tool in the Civil War medical arsenal. By providing vital comfort to the wounded and serving as a boon to overwrought surgeons, they were arguably the era’s most important medical development.

Our focus in this column is “general anesthesia”—the state of the patient during a surgical procedure in which anesthetics are applied to the entire body to induce unconsciousness. (Local anesthesia is pain relief in a particular area—e.g., when powdered opium was applied to a soldier’s open wound.) General anesthesia offers three vital results for patients and surgeons: 1) analgesia (painlessness); 2) amnesia (memory loss); and 3) muscle relaxation.

A distinctly American invention, anesthetics first saw widespread use about 15 years before the Civil War. Crawford W. Long of Georgia reportedly conducted the earliest successful experiments, using anesthesia in surgery in 1842. Long, however, made no sincere effort to publicize his discovery until years after others had shared their findings.

Long was followed by Horace Wells, a dentist in Massachusetts who experimented with nitrous oxide. Wells tried to draw attention to his discovery, but his public demonstration in 1845 failed. Apparently, Wells’ patient did not reach complete muscle relaxation and was heard moaning, leading attendees to jeer at Wells with cries of “Humbug” and “Swindler.” Although the patient did indeed experience analgesia and amnesia, the inadequate levels of muscle relaxation was enough to end Wells’ career as an anesthetist.

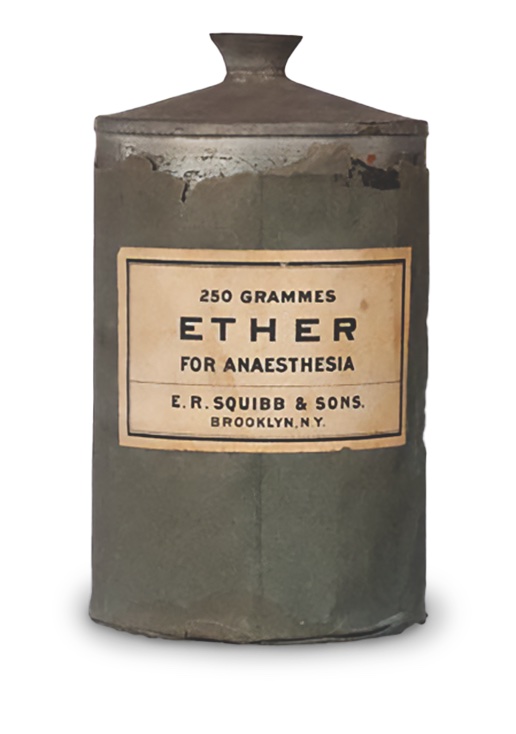

It was an associate of Wells’—dentist William Thomas Green Morton—who demonstrated the use of ether as an effective anesthetic. During a procedure at Massachusetts General Hospital in October 1846, surgeon John Warren successfully removed a tumor before an audience of prominent medical professionals. Morton’s demonstration sparked the first general campaign in favor of anesthesia as a safe and efficient means of preventing shock and pain during surgery.

Morton, it should be noted, later served as one of the Civil War’s only dedicated anesthetists. Union wounded surely appreciated his help when he served in field hospitals during fighting at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Spotsylvania.

Ether, however, would be surpassed by chloroform as the most popular form of anesthesia during the war. Not even a year after Morton’s successful ether demonstration, experiments with chloroform were already taking place. According to Robert Reilly, a Civil War-era doctor, “Chloroform was preferred because it had a quicker onset of action, could be used in small volumes, and was nonflammable.”

As another expert at the time was quick to point out, “mixtures of ether vapour with atmospheric air are highly explosive and have frequently given rise to frightful accidents.” U.S. Army surgeon W.W. Keen had just such an experience in his hospital after the Battle of Gettysburg, recalling: “The only available light was five candles…suddenly the ether flashed afire, the etherizer flung the glass bottle of ether…in one direction and the blazing cone fortunately in another direction. We narrowly escaped a serious conflagration.”

Reflecting on the event, an older and wiser Keen confessed: “I must admit gross thoughtlessness. My only consolation is that the patient suffered no harm.”

Not only was chloroform safer, but it was also more effective. Yet that did not stop the use of ether. According to The Medical and Surgical History, about 14 percent of procedures relied on ether and 9 percent used an ether-and-chloroform mix. Those numbers represented a division between field and general hospitals. The authors of the report wrote that chloroform was almost uniformly used in field hospitals, while ether was frequently used in general hospitals far behind the lines.

The authors also tabulated the reported incidents of anesthetic use among Union forces during the war, and the findings are telling: At least 80,000 surgeries were performed with some form of anesthesia in the North, only 254 without (a rate of 99.7 percent).

It is interesting that a tiny number of surgeries were performed without anesthesia by Union doctors who did have access to ample supplies of both ether and chloroform, perhaps because those surgeons feared anesthetics might induce a hemorrhage or pyaemia (blood poisoning) and therefore slow recovery time.

In rare instances, chloroform wasn’t available. Such was the case for Private James Winchell of the 1st United States Sharpshooters. Wounded in the arm and captured during the Battle of Gaines Mill in June 1862, Winchell, along with hundreds of fellow wounded prisoners, were not treated by Confederate doctors. Instead, a single captured Union surgeon was instructed to perform every operation, with the help of a sole attendant. Winchell waited for days for his procedure, during which time his wound festered. Finally, as Winchell recalled: “About noon July 1st, Surgeon White came to me and said: ‘Young man, are you going to have your arm taken off, or are you going to lie here and let the maggots eat you up.’ I asked if he had any chloroform or quinine or whisky, to which he replied, ‘No, and I have no time to dilly-dally with you.’”

Perhaps 125,000 surgeries involving general anesthesia were performed on both sides during the war, giving surgeons unprecedented experience with the procedure. The Confederacy used anesthesia much like the North did and held as much regard for the practice as their Northern counterparts. However, because Confederate medical records were burned in Richmond at the end of the war, we should avoid projecting too much on the South using only Northern sources.

Some historians have argued that Confederate soldiers were more likely to go under the knife without anesthesia because of supply shortages in the South. That, however, ignores key factors.

Again, anesthesia was a priority for Confederate surgeons, as the military medical consensus on the necessity of anesthetics was cultivated in the antebellum period, and there was effectively no resistance to acquiring, producing, and using them during the war. Hunter Holmes McGuire, Stonewall Jackson’s famed doctor, asserted, “in the corps to which I was attached, chloroform was given over 28,000 times,” and Julian John Chisolm, one of the most noted Confederate medical experts, claimed to have performed or observed 10,000 surgeries that used anesthesia during the war.

Several Confederate laboratories were constructed for chloroform and ether production, from Virginia to Texas. According to historian Michael Flannery, Chisolm’s laboratory in Columbia, S.C., was considered so important that he “asked for and received the single-largest Confederate warrant for medical supplies, more than $850,000, issued on April 13, 1864.” For the cash-strapped Confederacy, that says a great deal.

Another factor in anesthesia use in the Confederacy is that very little chloroform was needed to induce general anesthesia, on average only about a shot glass worth.

An underdosage, however, might have occurred after Stonewall Jackson was wounded by friendly fire at Chancellorsville and had his left arm amputated by McGuire. According to Jackson’s adjutant general, Lt. Col. Alexander Swift “Sandie” Pendleton, the general admitted to him: “I had enough consciousness to know what [McGuire] was doing; and at one time thought I heard the most delightful music that ever greeted my ears. I believe it was the sawing of the bone.”

We can only speculate whether Jackson, or any other wounded Confederate, was intentionally underdosed. During the war, it was up to individual surgeons to determine how much anesthesia to give their patients, rather than relying on codified guidelines. Not until World War I did the anesthesia community enact the first true systematic approach to monitoring—a multi-stage system created by Arthur Guedel to evaluate a patient’s precise state under anesthesia. Accordingly, in the first stage, patients would experience “disorientation”; in the second, “excitement”; and the safest phase to perform surgery was deemed the third stage.

During the “excitement” phase, the patient reportedly “may exhibit…muscular movement, phonotation, staring eyes, irregular respiration, etc.” To untrained eyes, it might appear that an insensible and unconscious patient had been given no anesthesia at all.

A further variable was the method by which anesthesia was administered. Surgeons on both sides preferred to use a cloth rather than manufactured inhalers. As Chisolm noted: “The best apparatus is a folded cloth in the form of a cone, in the apex of which a small piece of sponge is placed.” Union surgeon Dr. Valentine Mott agreed that “it is best to employ no special apparatus,” but also noted that a cloth “in the folded condition…might interfere too much with respiration.”

The application of anesthetics was inconsistent during the war, and there was no empirical and uniform guide on how and when to apply them. Nevertheless, more than 100,000 wounded soldiers ultimately benefited from the innovation. The final word perhaps should come from Stonewall Jackson himself. Despite Pendleton’s underdosage claim, McGuire recalled that as he applied the chloroform, the mortally wounded general drifted into unconsciousness: “As he began to feel its effects, and its relief to the pain he was suffering, he exclaimed, ‘What an infinite blessing!’ and continued to repeat the word ‘blessing,’ until he became insensible.”

Kyle Dalton is the National Museum of Civil War Medicine’s membership and development coordinator.