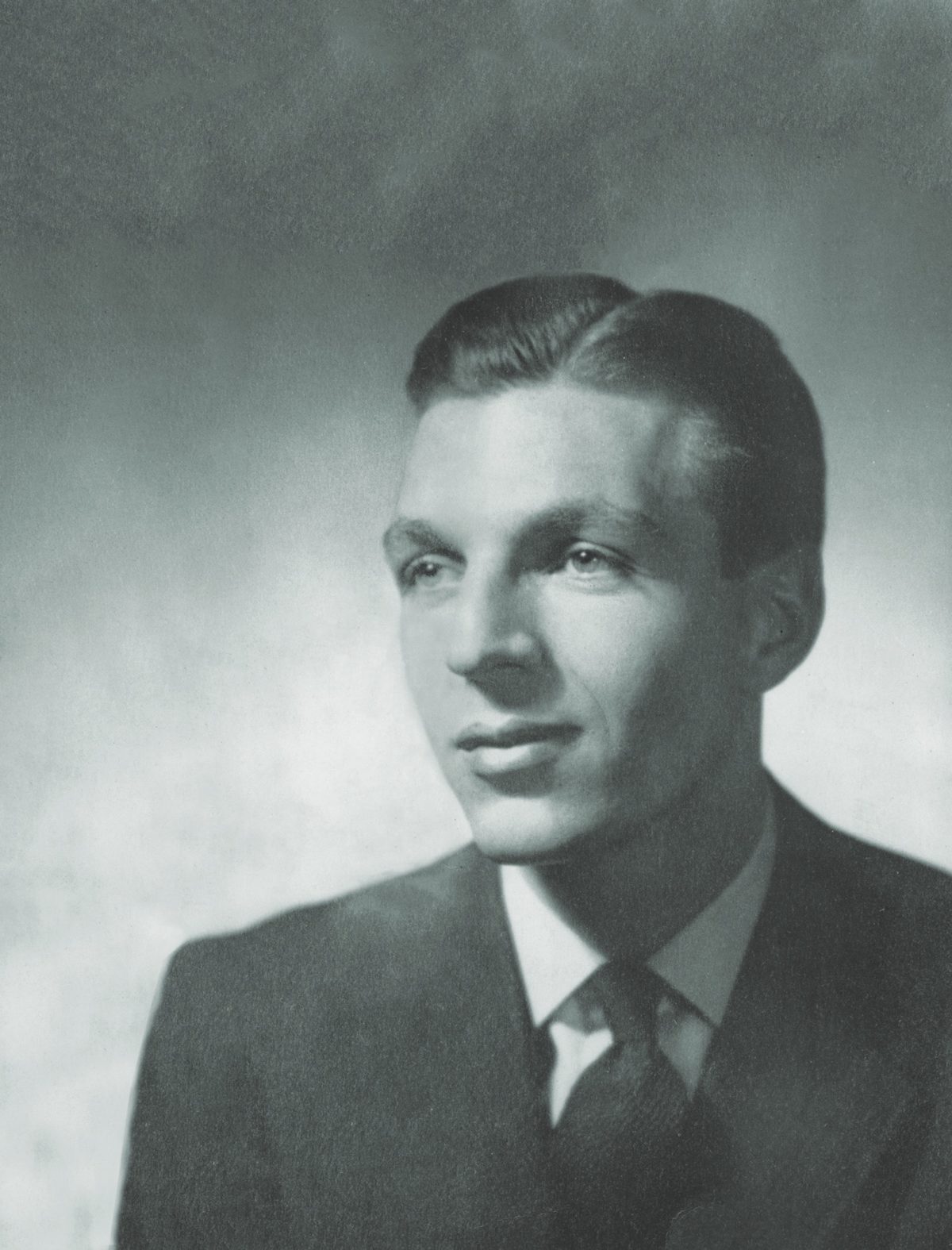

Richard C. Hottelet was born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1917, to German-immigrant parents who spoke no English at home. After he graduated from Brooklyn College in 1937, Hottelet, who was fluent in German but had no clear career plans, enrolled at the University of Berlin. But an encounter with a brownshirted professor led him to drop out of school, and in 1938, at age 23, he took a job in the Berlin bureau

of United Press, the Associated Press’s scrappy competitor, where he, like other “Unipressers” of the era, toiled under the slogan “Get it first, but FIRST, get it RIGHT.”

One morning in 1941, the Gestapo arrested Hottelet on “suspicion of espionage” for allegedly passing information to his girlfriend, an employee of the British Embassy. He was imprisoned for four months and then released as part of a U.S.-German exchange.

On returning to the United States, Hottelet joined the newly created Office of War Information, but in 1944 Edward R. Murrow, the legendary broadcast journalist and war correspondent, recruited Hottelet for his team at CBS News. Hottelet would go on to broadcast the first eyewitness account of the Allied invasion of Normandy and to cover Operation Varsity, the huge Allied airborne offensive across the Rhine River, during which he was forced to parachute to safety out of a plane shot down by enemy fire. He was the first U.S. war correspondent to enter Germany and reported from the newly liberated Buchenwald death camp, which he described as “a striking catalogue of inhumanity.”

In 1960 Hottelet became CBS’s correspondent for the United Nations, and for 25 years he appeared regularly on such CBS News programs as the CBS Evening News and Face the Nation. After leaving CBS he wrote commentary pieces for the Christian Science Monitor and became a guest lecturer at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. He died in 2014 at age 97, the last surviving member of the “Murrow Boys.”

On Sunday, August 3, 1941, dozens of newspapers across the country published the narrative that follows: Hottelet’s first-person account of his imprisonment by the Nazis earlier that year.

NEW YORK, Aug. 2—The doorbell of my Berlin apartment rang at 7 a.m. on Saturday morning, March 15. Instead of the plumber I expected to fix a defective sink, I found seven men in the hallway.

They crowded in immediately, showed their little identification tabs as members of the secret police and told me to get dressed and come with them.

They watched every movement as I washed and dressed. Despite my repeated questions they refused to say why I was wanted.

Several of them took me downstairs while the others started to go through my desk and personal belongings. Although my roommate, Joseph W. Grigg Jr., appeared while they were taking me out, I wasn’t supposed to speak to him.

I was taken by car to the old police presidium at the Alexanderplatz in the middle of Berlin. A member of the secret police there informed me I would have to be their “guest” probably over the week-end, until certain papers arrived from another department.

I was finger-printed and photographed. Then I was placed in a cell in the police prison in the same building. My first prison lunch consisted of sour cabbage.

That evening I was called up for preliminary questioning. Information as to why I was being held was refused. I also was refused reading matter, and my eyeglasses were taken from me “to prevent suicide.” My first formal questioning did not take place until the following Tuesday. Those first three days were the hardest and longest I ever spent.

I spent the time looking out the window, which I could just do by standing on the one stool in the cell, and reading the various inscriptions on the wall.

In addition to the stool, the only furnishings were a cot with spring mattress, a small shelf and a toilet in the corner.

Obviously various foreigners had occupied the cell before me. Someone, probably an Englishman, had scratched into the wall: “Home, Sweet Home, dear mother where are you?” There were also inscriptions in Russian, and someone had scratched “Vive L’Internationale” on the wall.

I was not allowed to sit or lie on the cot from 6:30 in the morning until 4:30 in the evening.

The weather was cold and the heating inadequate. I wore the hat, overcoat and gloves in which I had been taken to Alexanderplatz. The prison windows were not blacked out, therefore no artificial light ever was turned on.

In this prison the daily breakfast was a piece of dry black bread and ersatz coffee. Lunch consisted of bean, noodle or barley soup or a sour brew of dehydrated carrots. Dinner was again dry black bread and ersatz coffee, with a piece of cheese added as a special treat on Saturdays only. Occasionally jam or margarine was spread on the bread.

The prison was very old and the cell was very dusty. But since it had been fumigated recently I had no vermin.

Arrested on Saturday I was finally told on Tuesday, at my first formal hearing, that I was being held on “suspicion of espionage.” The secret police were very friendly and stated: “We are your friends and want to help you.”

When I flatly denied any espionage activity, they looked at me meanfully and said: “We want to get to the bottom of this and when we want information we get it. We are far too decent to use the brutal methods of the American police, but we can try klieg lights if we can’t get answers any other way.”

I was questioned sometimes twice a day, one session lasting until after 10 o’clock at night during that first week. By the end of the week the friendliness of the secret police had changed.

Klieg lights were referred to more frequently and I was told once: “You won’t feel quite so confident when you are sweating under the lights and we throw questions at you.”

During that first week I had a visit from a member of the American consulate in Berlin. I also received a suitcase full of clean clothes. For some unexplained reason the soap, tooth brush and tooth paste sent with the clothes were not given to me.

During all the weeks I spent in Alexanderplatz I had only two books to read, sent by friends. I was alone in a five foot by ten foot cell. I had no work of any kind to do. Most prisoners had had permission to purchase daily newspapers. This permission was denied me, but I managed occasionally to obtain a newspaper.

Numerous nationalities were represented in the prison. There were Russians Czechs, Poles, Japanese and at least one Italian. There also were several Catholic priests.

During the first few weeks all of us were taken out of our cells half an hour weekly for exercise. This consisted of marching and countermarching in a circle around a small courtyard which measured about 15 by 40 yards. As the weather improved we were led out for two half hour periods weekly.

Theoretically we were allowed to bathe every two weeks, but in the seven weeks I was there I had only one bath, two minutes under a hot shower. We could, however, occasionally, receive pails of hot water to wash ourselves in the cell.

Sessions with the secret police became less and less frequent during the last few weeks in Alexanderplatz. They never mistreated me. But shortly before I was transferred to another prison I was told flatly: “You will sit until you confess. You will soften up. You’ll be soft as butter. We’ve got plenty of time.”

On May 31 was transferred to the so-called investigation prison, Moabit, in another section of Berlin. It’s a four-story building housing about 2000 prisoners, including women.

Here the prison routine was much stricter. There was no possibility of clandestine exchanges with other prisoners. We were not allowed to smoke. But the food was better. We occasionally received a piece of sausage and on Sundays usually a piece of salt pork weighing about two ounces and potatoes with sauce. Once or twice there was a piece of fish or an egg. Otherwise the compositions of the meals was much the same as at the Alexanderplatz. But we did have salt at Moabit, to season the soup, which needed it.

The trusties who handed us our food as we stood in the doorways of our solitary cells frequently gave me large numbers of potatoes which I would save and eat over a period of several days, when I felt particularly hungry.

After four weeks at Moabit I was allowed to purchase a daily newspaper and also to receive two books weekly from the prison library. The guards automatically brought me English books but the selection was not always happy. One was The Fuel Problem of Canada. Another was a volume of British verse for young women published in 1867.

I received the first volume of Westward Ho, but the library lacked the second volume. Apart from that I read Robert Louis Stevenson, Sir Walter Scott and a volume of Robert Burns’ poetry. By far the most interesting reading, under the circumstances, was Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, which he wrote while serving a two-year prison sentence in England.

We were given “work” at Moabit in our cells. This consisted of pasting together paper and cellophane bags, pasting tissue paper over the windows of doll houses and twirling little throwaways for the Reich lottery. We were paid for this work, and at the end of my nine weeks at Moabit I collected my full salary of 4 1/2 marks ($1.80).

Church services were held every two weeks, but those of us in solitary confinement were allowed to attend only once a month. I was allowed to hear mass in the prison chapel with only one or two other prisoners. The regular services were barred to us.

The day’s routine consisted of getting up at five minutes to 7, washing, eating breakfast and then being taken out for a half hour’s exercise, every day except Sunday. Exercise was taken in a courtyard which had trees, grass, flowers and growing vegetables. Half the time we marched in circles, the other half we did calisthenics.

We were given regular army marching orders, and I had to learn when the command “Forward, march” was given to goosestep the first three paces. Most of the prisoners had had military training and the goosestep went off rather well.

After exercise we were marched back to our cells and locked in for the rest of the day. Lunch was at 11:30, supper at 4:30. As long as we had “work” to do in our cells we were not allowed to read until supper. Compulsory bedtime was 9 p.m., but we could retire any time after 4:30.

The monotony of the routine was depressing. Anything out of the ordinary, unlocking of the cell door for completed paper bags to be taken out and new work brought in, was a distinctively pleasurable event.

Meal time and exercise time were marked by strokes on a bell. The entire day’s routine was carried out in strict, almost military fashion. Whenever a guard unlocked the cell we had to jump to the window, close it, stand at attention, give our cell number and whether we were in jail for investigation or serving a sentence. The guards were strict, but most of them not unfriendly.

The hard wood bed with its straw mattress and blanket had to be arranged in a certain way. If not made up properly more than likely upon returning from the exercise period in the morning one would find everything in wild disarray where it had been thrown by the inspecting guard. There were periodic inspections of the wash basin and bowl, cup, knife and spoon, and the zinc wash basin had to be polished with sand until it shone.

Twice daily we received half gallon earthenware jugs full of water. With that we had to wash ourselves, our dishes after each meal, and flush the ancient contrivance which was the toilet. Once weekly we were given half a pail of water with which to wash the cells.

Prisoners with money deposited in the prison finance office could purchase various necessities from the prison canteen—tooth paste, tooth brushes, combs, ink, writing papers, shoe polish. Shoes had to be kept polished. Prisoners were allowed to write one letter every two weeks and receive them at the same intervals.

Theoretically, we were to be shaved twice weekly by prisoners who were barbers in civil life. But often the guard, seemingly in a hurry, would open the door, glance in a moment and say: “You don’t look as if you needed a shave, and, anyway, you’re not going anywhere.” He would wink and shut the door.

Hair was cut at the discretion of the barber, and with little regard for the esthetic considerations. It was either clipped off almost completely or in a circle around the back and sides of the head, leaving the top completely untouched.

Shortly before I was released I requested extra rations, because I had lost 15 pounds since being arrested. I was taken to the doctor, who politely but firmly refused, on the grounds that I had regained a few pounds since my transfer to Moabit.

Talking with other prisoners though the window or exchanging books and newspapers were punished by periods in a special cell in the cellar where the only food was bread and water and the only cot a bare board. Nevertheless I heard a good deal of whistling and cat-calling and even extended conversations between prisoners.

Some prisoners took special delight in whistling tunes out of the window, and I heard the “Internationale,” which frequently was taken up by a chorus, “Hang Out the Washing on the Siegfried Line,” and American dance tunes like “Melancholy Baby,” and “Night and Day.” American tunes were by far the most popular.

We had several air raids while I was in prison. At the Alexanderplatz prison we were allowed to remain in bed during a raid. But in Moabit we were required to get up, dress and sit under the window to avoid flak (antiaircraft) splinters. One bomb fell within a few hundred yards of the Alexanderplatz prison, but it was a dud and was detonated several days later.

At Moabit we were not allowed to receive any packages of food, clothing or cigarettes from the outside. But when an American vice consul visited me a few days before my release, he brought cigarettes and some chocolate. I was not allowed to take them to my cell, so I smoked furiously during the visit and munched chocolate. As a special favor, a prison official had me called from my cell two days later to eat the rest of the chocolate and smoke a few more cigarettes.

But visits with consular officials, the first during my first week in Alexanderplatz, the second during my last week in Moabit, took place in the presence of German officials and we were allowed to talk nothing but German and were forbidden to discuss my “case.”

The only other outsider I saw during my four months in prison was an attorney retained by the United Press and the American Embassy, who called twice.

My repeated requests to see a consular official or some of my friends either were never answered or deferred indefinitely. I was told once that the American Embassy had “dropped me.”

At the Alexanderplatz none of my numerous requests to receive visits, to be allowed to receive food, cigarettes and reading matter, ever seemed to reach the authorities. The day I was transferred to Moabit one of the Gestapo casually remarked: “Just this morning we received a number of your requests which seem to have been stuck somewhere and didn’t reach us until just now. Now it’s too late to do anything about them.”

My release on July 8 was a complete surprise to me. The guard unlocked the cell door and told me to pack my things. I asked whether I was being released or transferred to another prison. He said I was to be released, but I couldn’t believe it. I had been “released” from Alexanderplatz only to be transferred to Moabit, and I thought the same procedure might be followed again.

I collected my belongings, was locked in a transport cell for about an hour, then given my money and valuables and handed over to a representative of the American Embassy. Only then did I begin to believe I was being released.

From July 8 to 17, when I left Berlin, I lived “incognito” with a representative of the American Embassy, meantime collecting and packing my personal effects from my apartment. From the date of my release I had no more contact with the secret police or any other German officials.

I crossed the Franco-Spanish border on July 23. But the real feeling of freedom came as I sighted the New York sky line.

Now I know doors which I can open myself are something to be thankful for and not to be taken for granted. MHQ