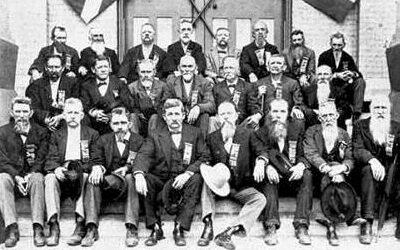

IN JANUARY 1908, Confederate veteran Thomas A. Elgin wrote this description of his aging comrades: “Old veterans whose unsteady steps and gray hairs speak of the many years gone by since in their youth they went forth to battle for principles.” Elgin was one of the elderly men who met regularly in Marshall, Texas, between 1900 and 1910 to reminisce about the events of 1861-65 and their lives since. They were members of the W.P. Lane Camp of United Confederate Veterans, whose failing bodies did not keep them from coming together faithfully every month. They shared their memories of the past, but there were also new battles to be fought for what they believed.

The core of the camp was formed by former members of the W.P. Lane Rangers, organized in Marshall on April 19, 1861, named for Brig. Gen. Walter P. Lane, “hero of three wars” (Texas Revolution, Mexican War, Civil War). The Lane Rangers were the first company raised in east Texas’ Harrison County for Confederate service. Lane’s service in the war included the battles of Wilson’s Creek (August 1861), Pea Ridge (March 1862), and Mansfield (April 1864). When the war ended, he returned to Marshall, federal pardon in hand, to devote his time to business interests and veterans’ matters until his death at 74 on January 28, 1892. His was the first military funeral ever conducted in Marshall, and he was so highly regarded that Texas Governor James S. Hogg ordered the flag atop the capitol in Austin lowered to half-staff in his honor.

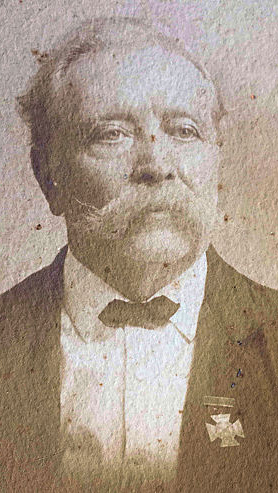

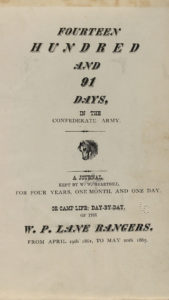

One of Lane’s original Rangers had been William W. Heartsill, who as orderly sergeant kept a daily journal of their activities that he turned into a limited-edition book in 1876 that today is extremely rare and valuable. After the war, Heartsill returned home to Marshall to live out the rest of his days, starting a successful mercantile business and holding political office as alderman and mayor. It was 60-year-old Heartsill who in April 1900 issued a call to the surviving Rangers to have their first reunion in 35 years. Out of that reunion came the W.P. Lane Camp, whose members included 23 former Rangers. They were soon joined by other former comrades still living in the area who read the newspaper or heard by word of mouth. In the next two years, membership would swell to 162 veterans. At their first meeting, they elected Heartsill camp commander. They were designated Camp No. 621 of the United Confederate Veterans on November 30, 1900. Heartsill was the paterfamilias of the organization. In the years that followed, as members inevitably fell by the wayside, one by one, he took it upon himself to write “an appropriate statement” about each one for publication.

One of the charter members of the Lane Camp was 59-year-old Thomas Elgin, who had begun as a private in the Rangers and rose to “third sergeant” by the end of the war. A native of Alabama, Elgin had been a printer before the war, so it seemed only natural that he become adjutant and recording secretary of the camp. He kept the minutes in a meticulous handwritten ledger, from which the period from January 1907 until March 1910 survives. Those minutes provide a window into the lives of these east Texas “Boys of ’61” some 50 years after the war.

The twin missions of the W.P. Lane Camp were fellowship and keeping the memory of the Lost Cause alive. The war was the biggest thing that had happened in their lives, and it was still front and center in their minds. The oldest member of the camp, W.S. Allen (born 1811), was also the oldest person in Harrison County.

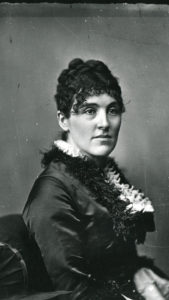

In the beginning, they held their meetings in the city’s YMCA hall but moved to the Harrison County courthouse in 1907. They met once a month, on Sunday afternoons, and were joined by the local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, UDC Chapter 412. The “Daughters,” as they were affectionately known, were part of the group not just because of a shared love for the South and its Lost Cause or even because their president was Mrs. Thomas Elgin, but because they lovingly ministered to the old gents. They prepared snacks, organized programs, did poetry readings, and held bake sales to raise money. They were “caregivers” before there was such a thing.

They also honored the men in another, unique way—by bestowing the Southern Cross of Honor on each one. These small bronze crosses had been created by the UDC in 1899 to recognize “loyal and honorable service to the South” during the war. Each cross bore the inscription, “Deo Vindice, 1861-1865,” loosely translated as “With God as Our Vindicator.” In 1903 they bestowed 55 crosses on the men of the W.P. Lane Camp. On January 6, 1908, Thomas Elgin was moved to write of the Daughters, “God bless them!” The little crosses were a frequent topic of discussion because they were emblems of a man’s service and therefore cherished by the recipient. They were so important that in March 1907, the veterans and ladies debated who was deserving of a Cross: anyone who had served or only those who belonged to a UCV camp and were “in good standing,” meaning their dues were paid up. The majority favored imposing qualifications, but it was far from unanimous.

Meetings typically opened with roll call followed by a prayer to the Almighty to bestow his blessings “upon all but especially upon the old vets wherever dispersed.” Much of the time that followed was spent swapping war stories. Battles and camp life were subjects that never failed to reinvigorate the oldsters. So too did sentimental poems recited by the Daughters and “the good old songs of other days” sung by children’s choruses or by the Daughters. The favorite songs were “Tenting on the Old Camp Ground,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” and surprisingly perhaps, “America,” all of which got more requests than “Dixie.” Occasionally someone would bring an old letter he had received during the war and read it aloud. Such letters invariably provoked shared laughter or shared tears or sometimes both.

The cherished memories of long-ago events were never openly challenged. It would have been insulting, and besides, it was possible to remember the same event in different ways. Consideration was allowed for failing memories. There was one given: the stories always lauded the Southern cause and Southern valor. The only objects of scorn were the villainous Yankees. One story that provoked lively discussion was when a member read from an issue of Confederate Veteran how General Robert E. Lee had offered his sword to Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox, then read an account by Grant saying it never happened. Grant’s denial was denounced by the members as another “Northern historical lie.” At that same meeting, a member related how he had fought as a VMI cadet at the Battle of New Market on May 15, 1864. He also recalled how after the battle President Jefferson Davis and former Virginia Governor John Letcher both came around to express their personal thanks to the cadets. Jefferson Davis may have been the failed president of a losing cause, but, like Lee, Davis was still a hero to these men.

Camp members had things to keep them busy other than swapping war stories. Every April they spearheaded “Decoration Day,” forerunner of our current Memorial Day, to place flowers on the graves of Confederate “heroes” (basically anyone who had fought in the war). They also took on the job of tending the Confederate monument erected in Marshall on the courthouse lawn in 1906, turned out en massefor the funerals of fellow veterans, attended reunions, and generally kept an eye on state affairs to make sure Yankee notions didn’t take over. The monument, a common soldier standing at ease with his musket, was a special source of pride. It had been erected through the efforts of UDC Chapter No. 412, ramrodded by Thomas Elgin’s wife and paid for by subscription. Many of the old gents of the W.P. Lane Camp dug deep to contribute a few dollars.

Each month’s meeting included the reading of the “mortuary report” containing the names of those who had died since the last gathering. Some months the list was long. The reports were always followed by a resolution of condolences to the families. By May 1908 the Lane Camp was down to 80 members, of whom seldom more than 15 attended a meeting. The reasons for the poor attendance were various. An increasing number were either too sick or too infirm to get out. Others did not attend because the meetings were on Sunday afternoons, and that was church day. A spirited debate occurred in UCV camps all over the state about the propriety of meeting on the Lord’s Day, and even found its way into the pages of Confederate Veteran, the Nashville, Tenn., publication about all things Confederate. Thomas Elgin reported other matters in his ledger that are minor but telling. At the August 1909 meeting, the chairman of the mortuary committee asked to purchase a typewriter to prepare the monthly reports of his committee. The chairman’s motion was tabled because the camp couldn’t afford the expense.

Membership was a thorny issue. New members occasionally applied, which if the man was not known personally to the membership, it had to be established whether he had actually served and with honor. Wartime rosters were sketchy or even non-existent if a man had served in a partisan unit. The cost of joining was 25 cents; annual membership dues the same. Upon joining a man got a certificate of membership, usually researched by the Daughters, which verified that he was a genuine Confederate veteran. Sadly, even 25 cents was more than some men could afford, and more than a few were behind on their dues, opening the question whether to permit them to continue attending meetings or bar them until they paid up. As the membership dwindled, every man present and accounted for was critically important to carrying on the organization. At the December 1907 meeting, criticism was voiced for known veterans who preferred to spend their time “sitting around the Courthouse yard” jawing and sunning themselves rather than joining the camp.

Judging by how the old soldiers addressed each other, it seems virtually everyone who had survived to this point was an officer. It was “Major” this and “Colonel” that, and even a “General” or two, because even if the man really had been an officer, he was “promoted” by his comrades in his sunset years. When Khleber Van Zandt, commander of the Robert E. Lee Camp in Fort Worth, came to Marshall in 1908 to rededicate the Confederate monument, he was introduced as “General Van Zandt,” though he had not risen above the rank of major in the war. Many veterans, including Van Zandt, were promoted by the UCV for service to the organization, but this UCV rank had nothing to do with actual rank in the Confederate Army.

Whenever they could, camp members attended one of the annual National Confederate Reunions, although attending required considerable expense and long-distance travel. The chance to see old comrades and maybe squeeze into the uniform one more time was worth it. Members who attended the reunions at Birmingham, Ala., in June 1908 and Memphis in June 1909 shared their experiences with those who had to stay home. Their accounts ranked only slightly below war stories in popularity on the camp meetings’ agendas for months thereafter.

With the passing of the decades also came a shared sense of comradeship with their former enemies. These old men were at the point in their lives where they could respect each other as honorable foes, “handshaking across the bloody chasm.” They could even respond favorably to a 1908 request from the Boston camp of the Grand Army of the Republic calling on all UCV camps in Texas to support a bill in the state legislature that would require the U.S. flag to fly over every schoolhouse in the state. The request was read aloud, as was Thomas Elgin’s response, which said the W.P. Lane Camp would support the measure so long as the flag “represents a reunited people” and not being flouted as a symbol of Yankee victory.

Another public matter riling camp members in 1908 involved the Texas School Board in Austin. Part of the board’s work was examining history texts and deciding which should be adopted for Texas schools. The old fellows were convinced that the board was trying to “foist upon our schoolchildren books that poison their minds against their own ancestors”—Yankee history in other words. They passed a resolution calling for textbooks to give “proper emphasis” to Southern history and that they be “thoroughly scrutinized to contain no objectionable passage.” Adjutant Elgin added in the minutes: “Southern books for Southern schools!”

The aging camp members understandably took an abiding interest in the Confederate Home for Veterans (opened in Austin in 1886) and the Confederate Women’s Home (a project of the UDC, opened in 1900 for veterans’ widows and wives). The Daughters were also the self-appointed overseers of the Veterans’ Home. While the Veterans’ Home was supported by public funds, the Women’s Home depended entirely on money raised by the Daughters. Lane Camp’s members were regularly solicited to donate, and they did so—$1 here, $3 there, whatever they could afford. The camp’s veterans realized that someday they or their wives might be residents of the homes. At the January 6, 1908, meeting, a rare dustup occurred between Commander W.W. Heartsill and the Daughters over conditions in the Women’s Home. Heartsill felt the living conditions in the Home were not up to snuff. The feelings were quickly smoothed over, and the meeting moved on. At the December 6, 1908, meeting, strong feelings were expressed about the state requirement that a man had to be destitute and swear to it before he could be admitted to the Veterans’ Home.

Pensions also appeared on camp meeting agendas. Unlike Union veterans of the Civil War who were pensioned by Congress, former Confederates were only pensioned by their home state, if at all. Southern legislatures were sympathetic, but not all were financially able to undertake such an obligation. It was not until 1899 that Texas began pensioning its Confederate veterans, and even then the level was hardly generous. To receive a pension, a veteran must have lived in Texas since 1880 and be disabled or indigent. The Lane Camp joined other UCV camps in 1909 petitioning the legislature to levy a “special tax” to provide “more liberal pensions.” Their pleas failed, however, even though more than a few former Confederate soldiers sat in the legislature.

The Lane Camp’s old soldiers spent much time discussing erecting Confederate memorials and attending dedication ceremonies. The problem was, as usual, money—every memorial or monument required funding, and their devotion outstripped their meager pocketbooks. They were constantly being asked to contribute to numerous memorial funds. In 1908, two years after subscribing to the memorial fund to put the soldier’s statue on the courthouse lawn, they were solicited for another fund to erect “a monument to the Confederate dead” in the Marshall cemetery. Most attended the June 3, 1908, dedication ceremony, but no matter how worthy the cause, their resources were limited.

The biggest dustup in 1908-09 was about the treatment of LaSalle Corbell Pickett, who had married Confederate General George E. Pickett (he was nearly two decades older than his “Sallie”) in November 1863 and had been his widow since 1875. She came to town in July 1908 as a speaker on the Chautauqua lecture circuit, and camp members considered it a great honor to have the wife of “the Hero of Gettysburg” in Marshall, the woman widely known as “Mother Pickett.” She was on a speaking tour through Texas with her visit to Marshall arranged by Professor W.D. Allen (aka “Colonel Allen”), a member of the Lane camp and director of the Female Institute of Marshall. She spoke on her favorite topic, the Battle of Gettysburg, relating it as if she had been there herself instead of getting all her information second- and third-hand. Lane Camp members were so excited to hear her that they voted to pay for the ticket of anyone who could not afford to buy one.

The problem arose when Sallie Pickett was rudely treated by some members of her audience. Thomas Elgin doesn’t explain exactly who did what, and whatever happened was never reported in the newspapers. But Elgin’s Lane Camp minutes claim Mother Pickett was badly treated, and the Southwest Chautauqua Association insulted her by only paying her $40 of the $100 they owed her. Indignant Lane Camp members unanimously passed a resolution decrying the “mistreatment and discourtesy shown Mrs. General Pickett,” demanding an apology to the lady and censuring the Chautauqua Association for trying to hornswoggle her. The Lane Camp agreed to submit a copy of the resolution to newspapers in Marshall, Dallas, and Houston—Marshall’s “dirty linen” was about to be aired for the whole state to see. The Lane Camp also reached out to Sallie Pickett, but by the time of its next meeting it had received a letter from her begging them not to publicize the matter. There is no indication from the minutes whether the general’s widow was ever paid everything she was owed.

In the minutes of Lane Camp meetings, as recorded in Elgin’s ledger, strong feelings of nostalgia and mortality come through loud and clear. The men muse about who’s going to carry on their good work after they are gone. Who’s going to preserve Southern history, honor the heroes of 1861-65, and defend the Lost Cause? They express the usual doubts about the younger generation. They were scornful of the “New South,” with its industrialization and movements to protect African Americans’ civil rights. And they never gave thought to Marshall’s black community or to the hundreds of thousands living under Jim Crow laws across the South. To those old veterans, the South would always be the land of magnolias and mint juleps and ever noble “Lost Causes.”