THE TWO PARAGRAPHS near the bottom of the Washington Post’s July 13, 1956, editorial page were easy to miss. They celebrated the life of a man named Alfred T. McCormack who had just died of cancer at the age of 55. The anonymous writer wanted the public to know that during World War II, “commanders from the man in the White House down to the platoon leader stood in his debt, whether they knew it or not, for that rare and useful tool of war, knowledge of the enemy.” This was a tribute that precious few American intelligence officers ever received. Just who was McCormack, and what had he accomplished?

The backstory has “Magic” in it. That is what some called the work of a handful of brilliant codebreakers—mostly civilian mathematicians working for the U.S. Army—who, with few resources other than their own persistence and a little help from their counterparts in the U.S. Navy, broke Japanese diplomatic codes in the 1930s. It was an amazing achievement, one that made it possible for them to read secret traffic between Tokyo and Japan’s embassies overseas.

The codebreakers decrypted a few hundred messages a week, which then had to be translated from Japanese to English. Army and navy intelligence officers, who were not codebreakers but generalists, would then decide which messages were worth further processing—usually no more than 25 a day—and distribute them to a handful of senior-most officials, starting with the White House. Each official usually saw nothing but the translated message itself, without any analysis or even any notes, and could not keep a copy to peruse at leisure; he had to absorb the message’s significance on the fly and rely on his memory to compare it to earlier messages.

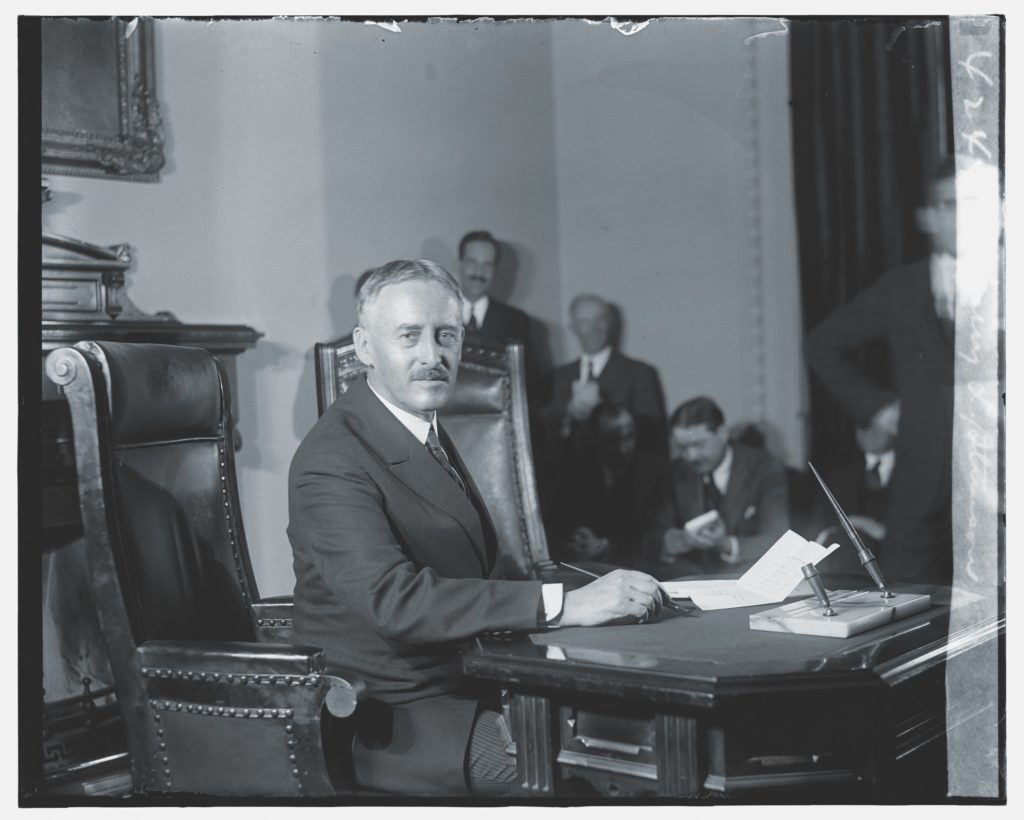

Both at the time and in retrospect, Magic was enormously important in the run-up to the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Most readers of the decrypted messages could see that Japan was preparing for war with the United States from the dispatches its foreign office sent to its embassy in Washington. But no one saw any decrypts that indicated exactly when and how the war would start. After the attack, Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson wondered how well the codebreakers were doing their work, or if their process was faulty. Today there is a consensus that nothing in Magic pointed to the attack. But in late 1941, the secretary did not know and wanted answers. The resulting inquiry would launch a quiet revolution in military intelligence—one largely directed by Alfred McCormack.

In 1941 THERE WAS NO DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE—only the Department of the Navy and the Department of War, each responsible for its own service. (War was responsible for the U.S. Army and the Army Air Forces.) Frank Knox, the Navy Secretary, reacted to the attack on Pearl Harbor by dashing off to Hawaii to conduct a whirlwind investigation. It was as if the former journalist was still working on deadline. His breathless report started the process of apportioning blame. Secretary Stimson was from a more process-oriented profession: the law, as practiced on Wall Street. He thought about what had happened and what the army should do. One of his priorities in those early days of the war was Magic and how best to harness its full potential. It was, he confided to his diary at the end of the month, “a matter I have had on my mind for some time.” Calling in Brigadier General Raymond E. Lee, the army’s senior intelligence officer, along with his personal advisor and troubleshooter, John J. McCloy, Stimson devoted time to the issue on the last day of the year. Had the army fully exploited Magic before Pearl Harbor? They weren’t sure, but their answer boiled down to “maybe not.” They now wanted to pay closer attention to the intercepts.

Stimson had lured McCloy, whom he affectionately called his “imp of Satan,” to serve at his side in Washington—first on an ad-hoc basis and then as assistant secretary of war. Even more than Lee, the cheerful, tireless McCloy was the right man to engage on the issue of Magic. The New York lawyer had a strong interest in intelligence, having dealt with the legal fallout from sabotage by German agents in America during World War I.

Like Stimson, McCloy nurtured the belief that it was best to rely on lawyers to take on the most difficult tasks of administration and government. Their training had supposedly sharpened their minds and taught them to see both sides of an issue; they thought of themselves as objective and incorruptible. The lawyers at McCloy’s firm, Cravath, Swaine & Moore, were handpicked from elite law schools. Thanks to the complicated suits they litigated—mostly on behalf of the largest corporations in America—Cravath lawyers were not afraid to roll up their sleeves for 70 hours a week and immerse themselves in oceans of data to find the grains of truth that mattered.

Magic had already generated thousands of pages of files; a Cravath lawyer could find patterns and meaning that others had missed.

McCloy recommended one lawyer in particular, Alfred McCormack, “who would have the organizing ability…that we wanted.” By the end of the December 31 meeting, Stimson had authorized McCloy to summon McCormack to Washington and offer him a job.

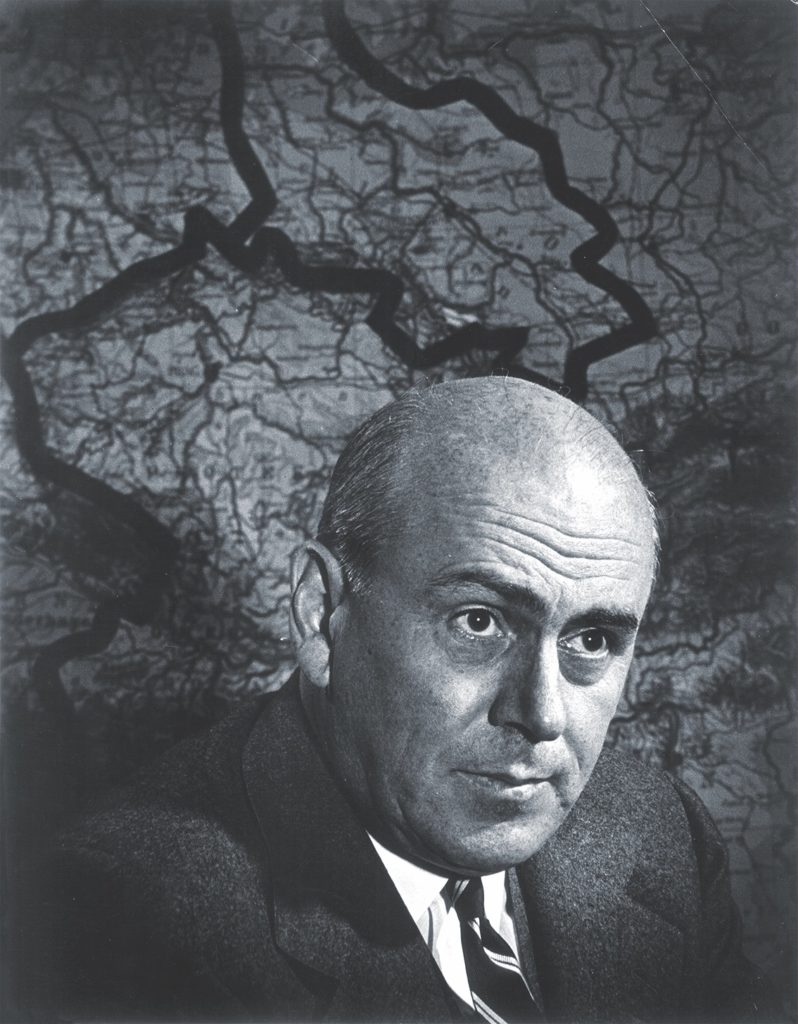

HE WAS ANOTHER INSPIRED CHOICE. A Brooklynite, McCormack had received a Phi Beta Kappa key from Princeton and emerged from Columbia Law School as a budding member of the country’s legal elite. After clerking for Supreme Court Justice Harlan F. Stone, he went on to practice law on Wall Street, becoming a partner at Cravath in 1935 and then a managing partner—one of the men who ran the firm. Even during the Depression, a partner at Cravath could not avoid becoming wealthy, and McCormack was no exception. In 1936 he was able to purchase a 250-acre estate in Connecticut. But, while hardly an incubator for the New Deal, Cravath had a tradition of public service. When Stimson and McCloy reached out from Washington early in January 1942, McCormack did not hesitate to make the journey to the capital to hear their proposal. Their exact words are lost to history, but the pitch amounted to: study the problem, come up with a solution, and implement it.

McCormack’s partners had long suspected that he was as interested in military history as in the law, and they were not surprised when he resigned from Cravath to do war work he could not discuss. On the first day of his new job, McCloy escorted him to the secretary’s suite in the utilitarian Munitions Building on Constitution Avenue that served as the army’s headquarters until the Pentagon opened one year later. Stimson took the time to welcome the man they had selected to turn what he called “the Magic papers” into “a really useful basis for inferring what the enemy was going to do.” With the title of Special Assistant to the Secretary, McCormack agreed to create a small “Special Section” in army intelligence. Though vague, his title implied that he answered only to the secretary himself—a fact that seasoned bureaucrats would grasp, making them far more likely to cooperate. If McCormack had any second thoughts or doubts about his ability to do the job, he did not express them. He believed he would succeed as long as he had the secretary’s support.

McCormack had the physical presence to match his legal brilliance. Not a small man at about six feet and 220 pounds, he filled out the dark suits he favored. With a full head of brown hair conservatively parted close to the middle of his scalp, he gazed intently through round, horn-rimmed glasses, often with a hint of a smile. Those who matched his brilliance liked him, no matter their own status. Those who did not would be shown the door; McCormack did not tolerate inferior work. Like McCloy, who seemed to never age, the 41-year-old had boundless energy. For the next two months he put in long hours surveying the situation: studying back materials, investigating how the army processed intercepted messages, and regularly conferring with McCloy and military intelligence officers. It was not unlike preparing a complicated legal case.

McCormack’s training made him a formidable researcher and a compelling, fastidious writer. He loved words—especially his own words—and enjoyed writing. He even liked reading his compositions back to himself and his colleagues. Three weeks after starting work, he reflected in a thoughtful memorandum for General Lee that Magic enabled Washington to “look behind the enemy’s eyes, into his emotions and his brains” and see “that he is a formidable adversary, cunning, patient, infinitely painstaking, highly intelligent and wholly un-moral.” (In contrast, he thought the United States was “without a clear idea of either its ultimate purpose or its immediate objectives,” and unprepared to translate “its verbal thunderbolts” into action—biting criticism of U.S. policy from the new hire, clearly not a Roosevelt devotee.)

McCormack’s intent was not to point fingers but to puzzle out how to make the best use of Magic going forward. His goals, he said, were to “examine and study the past…for any light it may throw on current and future problems” and “to make sure that the material is used with maximum effectiveness.” He looked at the separation between army codebreakers and the intelligence officers who worked in different chains of command, and the absence of a feedback loop between the two offices. Army intelligence was not telling the codebreakers what to intercept and process. Instead, it was simply taking in what the codebreakers sent over, having trusted them to decide.

McCormack saw the folly of sending raw intercepts to busy decision-makers: “The daily reporting of current messages was only one part of the job; the real job was to dig into the material, study it in light of outside information, follow up leads that it gave, and bring out of it the intelligence that did not appear on the surface.” He knew from years of experience with “masses of material” that you had to comb them “over and over” to glean their true value. Drawing on other sources, checking facts, and identifying trends, research would form the basis for the kinds of reports senior leadership needed.

McCormack thought that army codebreaking should stay where it had been for years—as part of the War Department. Nevertheless, he came perilously close to stating that intelligence was too important to be left to most military officers. He thought that regular officers seemed to have “a certain supine attitude toward intelligence” work and “disagreed with the notion that any reserve officer, or [even] any civilian who had been graduated from college was qualified to handle cryptanalytic intelligence.” He wanted men with stronger analytical qualifications—people who could start with a lot of raw data and find trends in it. Like McCloy, he believed the ideal candidates were “top-flight young lawyers, trained in research and the preparation of cases.”

Lawyers, he wrote, “are better fitted for intelligence work of the type that must be done in the War Department, i.e., what the Army calls ‘strategic intelligence,’ than is any other group in the community….” They could be leavened by “a couple of good economists and people trained in historical research, together with some language specialists.” McCormack’s vision was to bypass the army’s professional intelligence officers by using his new hires to create a standalone analytic unit that would take raw intercepts from the codebreakers and use them to produce finished intelligence.

McCormack completed his initial survey in March 1942 and, with Assistant Secretary McCloy’s and General Lee’s approval, prepared to assemble the staff he needed for his Special Section. The outsider started by acknowledging that he needed help from an insider in order to succeed. He was, an associate would say, “beautifully qualified” to stand up and run an elite bureau for analysis—but not a good fit for the army. McCormack would never mesh with army bureaucracy; he remained the foreign object that the military body would keep trying to reject.

EARLY ON MCCORMACK MET the officer who would offset that shortcoming and become his most important wartime ally. For some 25 years, Colonel Carter W. Clarke had been a regular officer in the Signal Corps, the organizational home for army codebreaking. Not a West Point man, Clarke had originally enlisted in the army and worked his way from the bottom up. He was trim and fit, and, at six foot two, slightly taller than McCormack and only a bit less energetic. He lacked McCormack’s intuitive knack for grasping the theory of a case, or even any specialized knowledge of intelligence. He openly occupied a point on the far right of the political spectrum—unusual among regular officers, who shied away from expressing their mostly conservative attitudes. But he had common sense and good judgment. He was not afraid to use colorful language if it would help get results. Using a polite euphemism for the actual words, McCormack recalled how Clarke described one general’s morning meetings as “rodent intercourse.”

In May 1942, Major General George V. Strong—who replaced General Lee as the army’s chief intelligence officer after Lee moved on to command the 15th Artillery Brigade stateside—told Clarke that his job was “to go in there and get along with that fellow,” meaning McCormack. Strong then turned McCormack’s Special Section into the Special Service Branch, soon shortened to Special Branch, and made Clarke its chief.

At Strong’s urging, McCormack accepted a wartime commission and, as the junior colonel, became Clarke’s nominal deputy. But for once seniority did not matter; the two men worked as a team.

As they staffed the Special Branch, McCormack and Clarke spent a disproportionate amount of time struggling with military and civil service regulations. It was almost easier to find and commission the lawyers that McCormack wanted as his officers than to bring on the lower-ranking specialists to support them. By painful stages over the next year and a half, the staff grew to a total of some 100 officers and 300 civilians. One of the officers, Thomas E. Ervin, later estimated that an astounding 85 percent of the officers were lawyers, while the remaining 15 percent were academics—roughly the mix McCormack had originally envisioned. There were so many lawyers that Ervin felt that it was like being back at law school and working on the law review.

First came the long hours. While other branches of army intelligence kept peacetime hours, the Special Branch was open for business from 7 a.m. (and sometimes earlier) until about 11 p.m.; McCormack’s officers did their best to finish the task at hand before leaving for the day, working 13 out of every 14 days researching, analyzing, and writing reports. Army codebreakers in the Signal Corps still intercepted, decrypted, and translated secret messages to and from Tokyo and Japanese embassies around the world. But now, instead of heading to army intelligence, the products of their work went to Special Branch, where McCormack’s officers would sift through a few hundred messages a week looking for ones that mattered. (That number would go up to a few thousand in 1943 as the army got better at breaking Japanese codes.) The clerical staff would then cross-reference messages and research their context. Finally, the officers would write a report that they would route to McCormack’s desk.

Most days the result was a compilation of reports known as the “Magic Summary.” The first summary appeared in spring 1942, double-spaced on heavy 8 1/2 by 11-inch U.S. Government stock, written in plain English, about 10 pages long, and bound in a spiral notebook with a hard cover. In place of what a reader would have received before Pearl Harbor—a translated enemy message typed onto a sheet of paper—the reader now saw a message in context. Was it a departure from past messages? How did it stack up against other messages from the same day? It was the difference between reading a telegram and reading a research paper or newspaper article on the telegram’s subject.

Summaries went to some 11 offices at the War Department, at least two at State, and 10 at Navy. The army and navy agreed to try to limit President Roosevelt’s reading only to Magic Summaries. This was not an attempt to deny him information, but rather to optimize his precious time. It was also an indicator of the summaries’ high value; Magic was the president’s principal source of strategic intelligence. Paradoxically, even though this was more than ever an army operation, it fell to navy officers detailed to the White House to actually carry the reports to Roosevelt. Like everyone else, Roosevelt had to return the read summary to a courier, who might have waited in an outer office. McCormack’s office kept careful notes of who saw what and ensured that all copies—except for those being saved for the record—were incinerated.

JUST WHAT DID THE READER find in these wartime summaries? Many of the reports were more important than exciting. Readers could learn about German strategy—as explained by Hitler to Hiroshi Oshima, the Japanese ambassador in Berlin, who sent detailed reports back to Tokyo. This was as close as the United States got to hearing secrets directly from the Führer’s mouth; no American or British spies were reporting from inside the German government. The summaries were also the sole source of information on the relationship between the Soviet Union and Japan. In 1942, the two countries were not at war even though they were on different sides. A Japanese attack on the Soviet Union, or vice versa, would have enormous consequences—as it did in the summer of 1945.

What specifically did Magic mean to the average G.I.? He would never hear of McCormack. But, as the obituary writer suggested in 1956, he owed a lot to the lawyer. It was thanks in large part to him that the Japanese soldiers fighting G.I.s in the Pacific were often ill-equipped and hungry; McCormack’s office played a crucial role in breaking Japanese shipping codes. This gave the navy the information it needed to sink Japanese ships carrying supplies to the front lines. Magic made an even more clear-cut difference at the tactical level in the European Theater. In late 1943, Ambassador Oshima went on a tour of Germany’s Atlantic coast defenses. Intercepted by Allied codebreakers, his reports comprised an invaluable guide to the defenses and helped to shape D-Day plans. On June 6, 1944, casualties were far lower than feared. McCormack’s Magic made it possible for many troops who waded ashore to make it off the beach alive.

At the end of the war, McCormack and his lawyers shed their uniforms and went back to their practices, leaving army intelligence to make its own way. McCormack once again found fulfillment in New York law. But he was proud of his wartime service and believed he had made a difference. The army agreed, bestowing a Distinguished Service Medal on him in 1945 for “exceptionally meritorious and distinguished services to the Government of the United States in a duty of great responsibility during World War II.” The continuing need for secrecy made it impossible to describe just how much he had done for the war effort and kept the real value of his work hidden for decades. ✯

This article was published in the August 2021 issue of World War II.