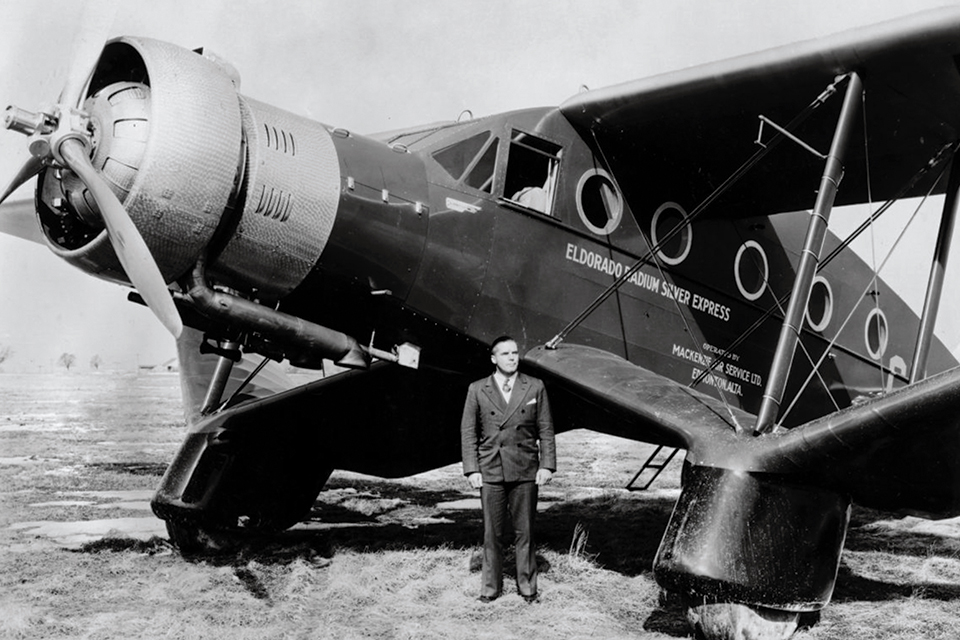

The Eldorado Radium Silver Express, a restored Bellanca Aircruiser, will soon be on view at a new museum in western Canada.

The single-engine Bellanca Aircruiser cargo and passenger airplane was designed by Giuseppe Bellanca, who had built Italy’s first aircraft and emigrated to the United States in 1911. The transport became a workhorse for the mining industry in northern Canada, especially the Northwest Territories. The Aircruiser could be equipped with wheels, floats or skis, which made it perfect for the harsh conditions of the Canadian north. Due to the triangular-shaped struts supporting its high wing and fixed landing gear, the airplane was nicknamed the “Flying W.”

In 1935 Eldorado Gold Mines Limited purchased Aircruiser CF-AWR and contracted with the Mackenzie Air Service of Edmonton, Alberta, for its operation. The Eldorado company had started in the 1920s searching for gold, then switched to mining silver. With the discovery in 1930 of uranium oxide at Great Bear Lake in the Northwest Territories, the company directors sought to tap the lucrative market for radium, which could be extracted from uranium ore. At the time a gram of radium brought $50,000 on the world market.

The Aircruiser, capable of carrying payloads of up to 4,000 pounds, was used to deliver uranium to Eldorado’s refinery in Port Hope, Ontario. In addition, workers were flown out of the Great Bear Lake mine for relaxation while sitting on the burlap bags of uranium oxide. It would later be revealed that the Canadian government knew about the potential adverse health impact of men sitting on bags of uranium oxide but ignored it. On return trips the aircraft carried supplies, dynamite and workers.

Located at Port Radium on Great Bear Lake, the mine was closed at the onset of World War II but reopened in 1942 with the start of the Manhattan Project and the drive to develop an atomic bomb. The mine and Port Hope processing facility became a key part of the top-secret project. In 1943 it became clear that the Germans were aware of the facility when, in his nightly broadcast from Berlin, propagandist William Joyce, aka “Lord Haw-Haw,” stated that “People at the Eldorado mine in northern Canada would be bombed shortly by our Japanese friends.” Security was tightened, but nothing happened.

CF-AWR was a workhorse in service of the Manhattan Project. With the end of WWII the demand for the uranium oxide increased and kept the Aircruiser in constant use. As the U.S. and other Western nations became major players in the nuclear industry, they relied on the Canadian ore. Tons of uranium oxide were mined but very little remained after refining for use in nuclear weapons or reactors.

In January 1947, while carrying a full load of uranium oxide, CF-AWR ran out of fuel, crashed and was damaged beyond repair near Sioux Lookout, Ontario. The uranium was recovered but the Aircruiser then sat for 27 years in the bush until volunteers from the Western Canada Aviation Museum, with the assistance of a helicopter from the Canadian Armed Forces, were able to recover what was left of the aircraft and transport it to the Winnipeg museum. The years of exposure to the harsh weather had rotted away the wooden structure and even the steel pieces were badly rusted. It was a difficult operation since trees and vegetation had grown over and into the aircraft fuselage.

Charged with preserving aircraft that played a major role in the region’s history, the Western Canada Aviation Museum employs specialists

and volunteers in its Restoration Department. The goal of the restoration team on every project is to ensure the completed aircraft is brought back as closely as possible to the original factory specifications.

The project was made more difficult by the fact that Bellanca had manufactured just 23 Airbuses (an earlier version) and Aircruisers. The only other surviving Aircruiser is in the Erickson Aircraft Collection in Madras, Ore. Studying that still-airworthy example was one of the first steps. Others on the restoration team traveled to the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C., to study and copy the original design drawings. The Erickson collection donated a spare set of wheels and tires to the team, though the Winnipeg museum Bellanca is being restored for static display.

Since the aircraft had been in operation for 12 years, parts had been replaced over time and there were some spares available. The team learned that several of the aircraft doors and windows had been incorporated into area trapper cabins. Machinists Dick Thornhill and Gordon Windat created a new aluminum gearbox. Gears, shafts and universal joints were also fabricated. A new instrument panel was constructed by studying old photos and the Erickson plane.

Ron Morrison, a restoration specialist who was involved in the project, said, “We’ve done so much with so little for so long that we can do anything with nothing.”

Slowly over the years the aircraft began to take shape. The woodwork, engine and fabric repairs were made and a correct propeller was located and installed. CF-AWR received a fresh coat of paint in the original green and gold colors and the official registration markings it carried when it left the factory.

At present CF-AWR is stored at the Southport Aerospace Centre outside Portage La Prairie, Manitoba. There is a new museum under construction and all the aircraft are in storage until its opening in 2022. The new Royal Aviation Museum of Western Canada will be located on the main transportation loop of Winnipeg’s Richardson International Airport. The central location will make it easier for visitors to view the historic aircraft collection, including the rare Eldorado Radium Silver Express.

This article originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe today!