IT LOOKED LIKE a milk run for the 82nd Airborne Division’s 504th Regimental Combat Team. The night sky was clear and moonlit as the paratroopers made the three-hour flight from Tunisia to Sicily. Some men dozed and others craned their necks to glimpse at the Mediterranean’s whitecapped waves below them. The smell of lacquer and gasoline filled their C-47 transport planes.

Less than two days prior, American and British troops had landed on the southern coast of Sicily and established a beachhead. Now, the 504th was en route to reinforce that beachhead. The flight would be entirely over Allied-controlled water and land, and the men would jump onto an airfield already in American hands. As the planes neared the Sicilian coast, the paratroopers’ “highest hope for a safe crossing seemed justified,” one of them recalled.

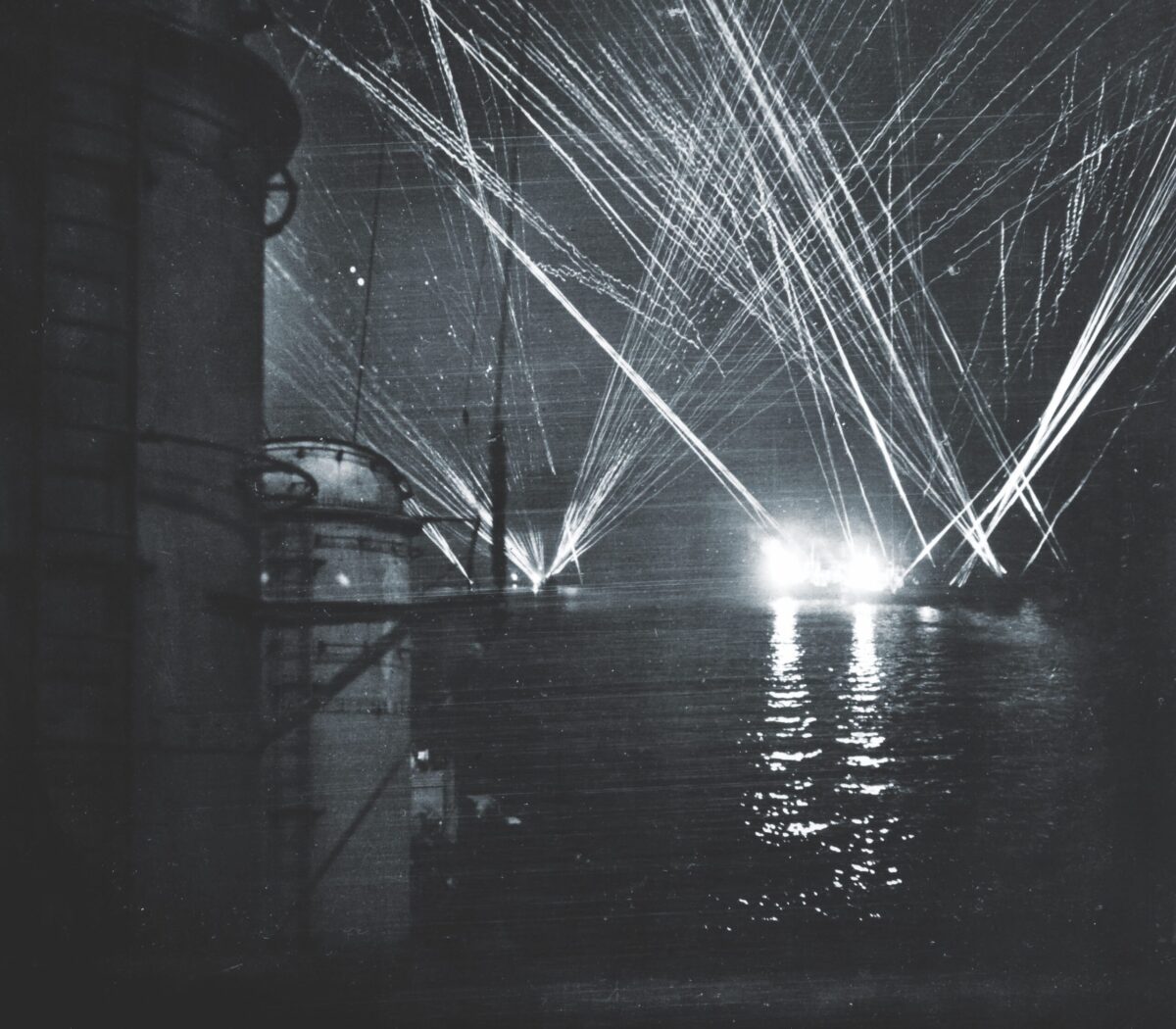

Then, in an instant, disaster struck. Tracers lit the sky and antiaircraft shells rocked the low-flying transports. Bullets and shrapnel ripped through wings, fuselages, and flesh. Planes caught fire and “tumbled out of the air like burning crosses,” one paratrooper recalled. The paratroopers and aircrews immediately realized that it wasn’t the enemy sending up this deadly wall of fire. To their dismay, a seemingly simple mission had inexplicably turned into a friendly-fire nightmare—one of the bloodiest such incidents of the war—and startled commanders soon realized they had a lot to learn about modern warfare.

Next Stop: Sicily

AFTER THE ALLIED INVASION of North Africa in 1942, the next stop was Sicily, the island at the foot of Italy. Its capture would solidify Allied control of the Mediterranean and provide a launching pad for attacks on the Italian mainland. The plan, named Operation Husky, called for the 82nd Airborne Division’s 505th Regimental Combat Team to jump behind enemy lines at midnight on July 10, 1943, followed by infantry landings on Sicily’s southern coast at 2:45 a.m. The 504th was on call, scheduled to jump any night thereafter, depending on how the campaign progressed. Allied commanders had high hopes for the paratroopers, but airborne operations were still in their infancy, and Husky would be the Allies’ most ambitious use of parachute infantry to date.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

The invasion took place on July 10, as planned. The 505th dropped behind enemy lines shortly after midnight. Although high winds and navigational errors scattered the paratroopers, they caused confusion among the German and Italian defenders. Landing before dawn, British and American troops established a beachhead and pushed inland.

Since well before the invasion, the 504th’s planned follow-up jump had gnawed at the commander of the 82nd Airborne Division. A 1917 graduate of West Point, Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, 48, was an intense man, described as “hard as flint”; Time magazine claimed he could “out-hike 90% of his men.”

What worried Ridgway was the danger of friendly fire when the 504th’s transports flew over the Allied invasion fleet anchored off Sicily. Because the 505th would jump before the invasion began, its transport planes would avoid the ships; after the landings, the 504th would have no such luxury. Weeks before the invasion, Ridgway demanded a guarantee from the U.S. Navy—over whose ships the 504th transport planes would fly—that it would hold its fire when his men passed overhead. The navy, however, refused to make a promise it wasn’t sure it could keep. Husky’s overall naval commander, British Admiral Andrew B. Cunningham, expected that ships would fire “at any aeroplane particularly low flying ones which approach them.” Ridgway stood his ground. Without a firm guarantee of safe passage, he said, he would recommend canceling the follow-up jump.

Patton Steps in

Under pressure from Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Husky’s American ground commander, the navy compromised. Three days before the invasion, on July 7, 1943, it agreed to provide a safe corridor: a two-mile-wide lane devoid of ships that the 504th could fly over without drawing fire. To minimize contact with the invasion fleet, the transport planes would take a circuitous route from their airfields in Tunisia, flying east to Malta, making a left sharp turn, and approaching Sicily from the east.

On July 11, Patton ordered the 504th to jump that night to reinforce the beachhead, with recently captured Farello airfield in southern Sicily as its destination. The mission was named Operation Mackall in honor of Private John Thomas Mackall, a 22-year-old paratrooper killed in North Africa. At 8:39 a.m., a coded message gave the 504th the green light: “Mackall Tonight Wear White Pajamas.” (“White” signified Farello as the drop zone.) Six minutes later, Patton radioed ground and naval units to “take every necessary precaution to prevent firing of any description on low-flying planes (C-47’s) which are to arrive over your area between the hours of 2300 and 0030 [from 11 p.m. until half past midnight] and which will be transporting the second increment of the 82nd Airborne Division.”

Getting the word out to all units was easier said than done. Decoding a radio message took time. Many radios had been damaged during the landings and communications centers were backed up. The ground units were actively engaged in combat and, beginning at 6:35 a.m., the vessels offshore had their hands full fighting off a series of air attacks. That afternoon, Ridgway walked the beachhead and learned that some army antiaircraft batteries hadn’t gotten the word yet. It wasn’t until 5:47 p.m. that the commander of the American component of Husky’s naval forces, Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, learned that the mission would take place that night.

At 7 p.m., 144 twin-engine C-47 transports from the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing began taking off from Kairouan, Tunisia, to drop the 504th’s 2,304 paratroopers over Farello. The long flight began uneventfully, with only a few stray shots from Allied ships near Malta breaking the monotony.

Heavy Luftwaffe air raids that day had given Patton second thoughts about the night’s mission. Army and navy gunners were “jumpy,” he thought, and he feared they would fire on the 504th’s planes. At 8 p.m., he tried to scrub the operation, but the C-47s were already in the air and out of radio contact. “Am terribly worried,” he wrote in his diary.

Patton soon had more reason to worry. At 9:50 p.m., less than an hour before the 504th’s arrival, the Luftwaffe launched its heaviest bombing raid of the day. Antiaircraft batteries let loose, and ships maneuvered frantically to dodge falling bombs. If gunners had been jittery before, they were now even more on edge.

The first C-47s reached Sicily’s coast at about 10:30 p.m.—ahead of schedule. They flew 35 miles over American-held territory to Farello and dropped their paratroopers without incident. The groups that followed met a different reception, as army and navy gunners mistook the C-47s for German bombers. A lone gun opened up and “immediately, as though a prearranged signal,” ships and guns on shore “fired a devastating torrent of antiaircraft fire,” said Captain Adam A. Komosa, a paratrooper inside one of the C-47s. The men watched in horror as “the whole coastline burst into flames,” one pilot recalled. To 505th commander Colonel James M. Gavin, observing with his men from below, it looked like “fireworks on the Fourth of July” as tracers lit the sky and shells exploded in the air. Above him, Komosa and his fellow paratroopers “felt like trapped rats,” watching “our own troops…throwing everything they had at us.” Each successive wave of planes received heavier fire. Without armor or self-sealing fuel tanks and flying at 1,000 feet or below, the C-47s were extremely vulnerable. “Like clumsy whales,” they “wheeled and attempted to get beyond the flak which rose in fountains of fire,” Komosa said.

Stricken planes caught fire, and men either jumped or fell from the burning aircraft. Several C-47s crashed with their paratroopers still inside, including one carrying Brigadier General Charles L. Keerans Jr., the 82nd’s assistant division commander. The plane carrying Lieutenant Colonel Leslie G. Freeman ditched 500 yards offshore, and navy gunners raked it with gunfire, killing or wounding 11 paratroopers and crewmen. The destroyer USS Beatty fired its 20mm guns at a downed C-47 before realizing its mistake and rescuing the survivors.

Unfriendly Fire

Planes that remained aloft took their hits, too. The one from which 504th commander Colonel Reuben H. Tucker jumped returned to its base with more than 1,000 holes in it. Several pilots reported being chased by friendly fire for 30 miles after they left Sicilian airspace. Eight planes headed back to Tunisia without dropping their paratroopers; their pilots felt it would be tantamount to murder to drop men into the heavy fire. For the pilots, crewmen, and paratroopers, “the safest place for us tonight…would have been over enemy territory,” one after-action report noted sarcastically.

On the ground, some people realized what was unfolding and viewed “this weird fratricidal disaster with a feeling of helpless frustration,” said infantry Captain Edward M. Solomon. Among them were Ridgway, waiting at the Farello airfield, and army corps commander Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley, watching from his headquarters at Scoglitti, on Sicily’s southwest coast. War correspondent Jack Belden screamed at the men firing at the planes, “Stop, you bastards, stop! Stop shooting!”

Paratroopers who successfully jumped from their planes were far from home free. Ground troops fired at them as they descended and after they landed. Some units claimed they had been warned to expect German paratroopers that night. Chaplain Delbert A. Kuehl and his group landed near a stone wall and came under fire. Shouting the password did no good and, for the first time in his life, Kuehl cursed. Unbeknownst to the paratroopers, the 504th’s password and counter-sign (Ulysses/Grant) were different from the ones given to the ground troops (Think/Quickly). Kuehl crawled to his left in a large circle. He snuck up behind the men firing at his group, tapped one on the shoulder, and told him they were shooting at fellow Americans. When Colonel Tucker hit the ground, he sprinted to five nearby tanks to stop the tankers from firing at his men. The paratroopers who survived were irate, and one gave Captain Solomon a profane earful. “His opinion of his Brothers-in-arms was not complimentary to say the least,” Solomon remarked.

Gruesome losses

THE NEXT DAY REVEALED the disaster’s full magnitude. Twenty-three planes had been lost, and 37 were heavily damaged. The 504th had suffered 81 dead, 132 wounded, and 16 missing. The toll for pilots and crewmen from the 52nd Troop Carrier Wing was seven dead, 30 wounded, and 53 missing. It would prove to be America’s second most costly friendly-fire incident of the war, eclipsed only by Operation Cobra a year later, when American bombs fell on friendly troops during the Normandy breakout, killing 111 men and wounding 490.

On July 12, theater commander Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the beachhead and conferred with Patton aboard Patton’s command ship, the USS Monrovia. Eisenhower, who was not yet aware of the friendly-fire episode, was angry with Patton for another reason: Patton’s skimpy reports on the progress of the landings. “Ike…stepped on him hard,” said Captain Harry C. Butcher, Eisenhower’s naval aide. But despite being dressed down for withholding information, Patton did not tell Eisenhower about the prior night’s catastrophe. Eisenhower learned of it only when he returned to his headquarters on Malta, and he hit the roof, firing off a blistering message to Patton.

“Ample time was obviously available for complete and exact coordination of movement among all forces involved,” Eisenhower wrote. Therefore, he concluded, “the incident could have been occasioned only by inexcusable carelessness and negligence on the part of someone.” He demanded “an immediate and exhaustive investigation…with a view to fixing responsibility,” and he wanted disciplinary action taken against those responsible. “This will be expedited,” he ordered.

Patton fumed and fretted. He saw the previous night’s episode as “an unavoidable incident of combat,” and believed he had taken “every possible precaution” to protect the airborne troops. Eisenhower was overreacting, Patton thought, because “Ike has never been subjected to air attack or any other form of death.” Patton feared the incident would cost him his job. “Perhaps Ike is looking for an excuse to relieve me…. If they want a goat, I am it,” he wrote in his diary.

Ridgway, too, questioned Eisenhower’s attempt to fix blame. Disciplinary action would be of “doubtful wisdom,” he believed, because responsibility was “so divided, so difficult to fix with impartial justice, and so questionable of ultimate value to the service because of the acrimonious debates which would follow.” Still, there was an urgent need to figure out what had gone wrong. Planners viewed airborne operations as essential to any invasion because paratroopers dropped behind enemy lines would disrupt enemy troop movements and communications. With the invasions of mainland Italy and France on the horizon, they had to figure out quickly how to avoid friendly-fire casualties.

Systemic Failure

In the end, no one was disciplined and Patton kept his job. The various boards and commands tasked with investigating over the next few weeks realized the failure was a systemic one, born of inexperience in airborne operations—not dereliction. “Many mistakes were made and many lessons learnt,” was the verdict of British Major General Frederick A. Browning, Eisenhower’s airborne adviser.

The main lesson was “the special hazard of flying over friendly naval surface craft,” wrote Major General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff. “Naval vessels are required to fire without warning on approaching unidentified aircraft,” he noted. Once a ship or shore battery opened fire, others would do the same. “AA [antiaircraft] firing at night is infectious and control almost impossible,” said Air Marshal Arthur Tedder, Husky’s air commander. Aircraft-recognition training was essential, but Ridgway also noted the “inherent difficulty of recognizing friendly aircraft at night, particularly in the case of unseasoned troops.”

The best way to avoid fire from a friendly fleet, General Bradley believed, was to avoid passing over it. Safe corridors were a must, but the two-mile-wide corridor used in Operation Mackall was too narrow. The lane should be at least 10 miles wide, investigators concluded. As a further precaution, all naval and ground units must be prohibited from firing at any plane whatsoever along the approach route during the time of the drop.

The investigators never officially determined whether it was army antiaircraft batteries on shore or navy ships that had fired the first shot at the C-47s. Transport pilots were faulted for failing to fly their prescribed routes, although some may have done so to avoid ground fire, and army investigators questioned the navy’s fire discipline. The German air attack shortly before the transports arrived was viewed as “an unfortunate circumstance” but readily foreseeable. The C-47s bore yellow recognition lights on their bellies to help those below recognize them as friendly, but gunners had either not seen these lights or recognized their significance. Unnamed ground commanders were criticized for failing to adequately alert their troops to the upcoming airborne mission, and no one had thought to make sure the paratroopers and infantry had the same passwords.

Ridgway took the long view and saw Operation Mackall’s casualties as necessary growing pains. “Deplorable as is the loss of life which occurred,” he wrote in August 1943, “I believe that the lessons now learned could have been driven home in no other way, and that these lessons provide a sound basis for the belief that recurrences can be avoided.”

The 82nd Airborne didn’t have to wait long to put these lessons to use. Two months later, on September 9, 1943, American troops invaded mainland Italy, landing at Salerno. Four days later, German counterattacks put the beachhead in jeopardy and the invasion commander, Lieutenant General Mark Clark, called for the 82nd as emergency reinforcements. “This is a must,” he told Ridgway. “Rigid control of antiaircraft fire is absolutely essential,” Ridgway replied.

The operation was similar to Operation Mackall. Transports would fly over Allied-controlled waters at night to drop the 504th on an American-held landing zone—but this time, Ridgway got the guarantee he had wanted in Sicily. Clark ordered all antiaircraft batteries on ships and ashore to hold their fire from 9 p.m. until further notice from him. To ensure the message got through, Clark met with the naval and ground commanders and sent representatives to give the word in person to all units. The C-47s flew a route that skirted the invasion fleet, and when the 504th jumped shortly before midnight on September 13, 1943, not a single friendly shot was fired at the paratroopers or their planes.

The Secret comes out

THE MACKALL DISASTER was common knowledge in the Mediterranean Theater, but strict censorship kept the home front in the dark. The episode might have remained hidden for years, but almost by accident, the story came out eight months later.

Sergeant Jack Foisie, a 24-year-old reporter for the army newspaper Stars and Stripes, came home on furlough after having covered the invasion of Sicily. On March 15, 1944, he shared his wartime experiences in a speech before the Commonwealth Club, a community group in San Francisco. He mentioned Mackall’s friendly-fire incident, saying, “The navy gunners kept right on shooting, and some 20 of our planes went down.” A wire-service newsman was in the audience and reported Foisie’s comments. The story ran the next day in newspapers across the nation.

The press confronted Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson with Foisie’s account, but Stimson dismissed it. “I can’t ask for a report on what every soldier says when he comes back,” he said. Because Foisie had inaccurately placed the blame solely on the navy, however, something more than Stimson’s brush-off was needed. The War Department confirmed the gist of Foisie’s account but carefully noted that the friendly fire had come from both “naval and ground forces.” Stimson was left with egg on his face. “The old Secretary’s bluff was called,” Time magazine chortled. But he was powerless to take any action against Foisie. The newsman had cleared his speech with a stateside army censor before delivering it.

Never entirely comfortable with military censorship, the press smelled a coverup and questioned why the incident had been kept secret in the first place. An Associated Press story pointedly noted that the War Department’s confirmation came “without explanation of the secrecy previously imposed.” New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey, who would run for president against Franklin D. Roosevelt that fall, thought he knew the answer: he accused the Roosevelt administration of “a deliberate and dangerous policy of suppression” of military missteps.

Readying for Normandy

THE NORMANDY INVASION, as the Allies’ most important and ambitious amphibious assault of the war, would be the acid test for airborne operations—far more complex than the operations in Sicily and mainland Italy, and involving many more paratroopers, transport planes, and ships. Both the 82nd and 101st airborne divisions were slated to jump behind enemy lines just hours before the dawn landings. All the chips were on the table; if the invasion failed, it would take months—if not longer—for the Allies to marshal the resources to try again, and Eisenhower believed paratroopers were essential to the invasion’s success. The transport planes would have to fly in darkness uncomfortably near the invasion fleet, and this caused “great anxiety” over the risk of friendly fire, noted Rear Admiral Alan G. Kirk, commander of the invasion’s U.S. naval forces.

Precautions were again taken based on the bitter lessons of Operation Mackall, including a 10-mile-wide safe corridor and timely notice to all ships of the precise route the transports would fly. Distinctive black-and-white markings called “invasion stripes” were painted on Allied aircraft to help those below recognize the planes as friendly. These safeguards worked: when the C-47s passed overhead, naval gunners held their fire, which Admiral Kirk credited to “careful briefing and good discipline.” Airborne operations would always be high-risk endeavors but, as Ridgway had predicted, the costly mistakes of Sicily would not be repeated. ✯

LESSON LEARNED

Psychology today

IN THE AFTERMATH of the friendly-fire mishap over Sicily, the U.S. Navy wondered why the destroyer USS Jeffers (DD-621) was one of the few ships to hold its fire when the American transport planes passed overhead. The answer pointed in a surprising direction: a middle-aged psychologist in Ohio.

Friendly fire had plagued the U.S. military since the first day of the war, when gunners in Hawaii shot down four F4F Wildcats flying to Hickam Field from the carrier USS Enterprise. The speed of modern warplanes and the stress of combat made it difficult for gunners to distinguish between Allied and enemy planes. The navy used the so-called WEFT system for aircraft recognition, which taught men to identify a plane by its component parts—Wing, Engine, Fuselage, Tail—akin to trying to read by examining each letter in a word. This system was cumbersome and inaccurate, leading sailors to grumble that WEFT really meant “Wrong Every [expletive] Time.”

Samuel Renshaw, a 50-year-old psychology professor at Ohio State University, thought he could help. He had developed a speed-reading method, and he believed his system would work for aircraft identification. In early 1942, he pitched his idea to U.S. Navy Lieutenant Howard Hamilton, a former Ohio State colleague. As an experiment, Renshaw taught his system to college students. When the students identified planes more accurately than naval personnel, the navy began sending small groups of officers to Ohio State that June to learn his system—but they still wondered whether Renshaw’s method would work in combat.

Renshaw emphasized “perception of total form.” Students learned to look at a warplane as a whole, rather than at its component parts, much the way reading is actually conducted—by recognizing a word instead of parsing every letter in that word. His main tool was the tachistoscope, a slide projector with a shutter that flashed images on a screen for increasingly shorter periods of time. Silhouettes of Allied and enemy planes were shown and, through repetition, students learned to identify a plane in 1/75th of a second.

In early 1943, Donald W. McClurg, a 25-year-old ensign, completed the Renshaw course and brought the system to the Jeffers. McClurg drilled the ship’s officers and crew on aircraft recognition every day from June 5, 1943, when he came aboard in Norfolk, Virginia, until July 9, 1943, when the Jeffers sailed the Mediterranean toward Sicily.

The Jeffers’s commander, William T. McGarry, was proud of his crew’s performance during the ill-fated air drop. “This ship did not take any friendly planes under fire during the period of this operation,” he wrote in his after-action report, noting that the Jeffers was one of the few ships whose crew had recognized the planes overhead as C-47s. He credited Ensign McClurg and his rigorous training program.

Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, commander of Husky’s American naval forces, also took notice. “Ships which had on board graduates of the Renshaw School at Columbus, Ohio, reported excellent fire discipline,” he wrote in his official report soon after Sicily was secured. Hewitt recommended that each destroyer-class vessel or larger have a Renshaw-trained officer on board to teach the method to its crew. “Adequate instruction can never reach too many officers and men,” he reflected, and the army and navy adopted the Renshaw system.

By the end of the war, 4,000 air, navy, and army officers had completed the 120-hour aircraft recognition course at Ohio State. They, in turn, taught the system to more than a million servicemen. As radar-based aircraft identification became more reliable, visual recognition became less important—but until electronic identification was fully perfected after the war, the Renshaw system remained the last line of defense against friendly fire. After the war, the navy honored Renshaw with its highest civilian decoration, the Distinguished Public Service Award. ✯

— Joseph Connor

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.