In the 1976 war film Shout at the Devil, based on the best-selling 1968 novel by Wilbur Smith and starring Lee Marvin and Roger Moore, a pair of ivory poachers are induced to wage guerrilla warfare in German East Africa during World War I. The climax of the film comes when Marvin and Moore board the German cruiser Blücher—hidden far up the Rufiji River while its crew repairs battle damage—and place a time bomb in the forward magazine, blowing up the ship.

The story is very loosely based on an actual incident involving the German light cruiser Königsberg, whose captain did steam the cruiser up the Rufiji in 1914 to overhaul its engines. Unable to get its capital ships within range to engage the cruiser, the Royal Navy enlisted the aid of noted hunter and scout Philip Jacobus Pretorius, one of South Africa’s most legendary figures. Pretorius helped the British find and destroy Königsberg. While nearly forgotten in naval history, the action is mentioned in English author C.S. Forester’s classic 1935 novel The African Queen.

Seine Majestät Schiff (“His Majesty’s Ship”) Königsberg was the lead ship of four light cruisers built by the Imperial Shipyard Kiel in 1905–06 to serve as fleet scouts in Germany’s home and colonial waters. Commissioned into the Kaiserliche Marine in 1907, Königsberg was assigned that June to escort Wilhelm II’s yacht Hohenzollern on a cruise of the Baltic and North seas, during which the kaiser met with cousin Tsar Nicholas II of Russia. For most of the next five years Königsberg served as an escort or goodwill ship on visits to various European neighbors. It also undertook a series of reconnaissance patrols in the Mediterranean, thinly disguised attempts at spying on the British bases at Gibraltar, Malta, Alexandria and Suez. Placed out of service in Danzig for 19 months of modernization work, Königsberg rejoined the fleet in January 1913.

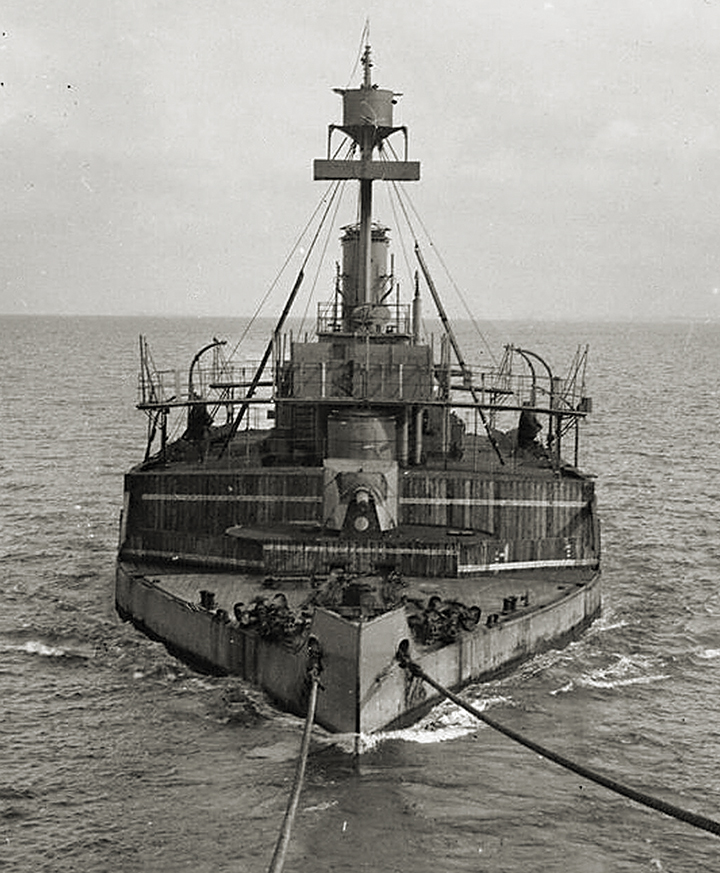

With a displacement of 3,400 tons and a length of 378 feet, Königsberg drew just over 17 feet of water. The cruiser’s crew of 14 officers and 308 enlisted men operated the ship and its main armament of 10 4.1-inch guns on single pedestal mounts. Each gun had 150 shells at the ready, giving the cruiser a considerable punch. It was also equipped with a pair of torpedo tubes below its waterline. Fast at 24 knots, Königsberg was able to chase down any merchantman afloat. With two triple-expansion reciprocating engines driving twin propellers, the cruiser boasted a range of nearly 6,000 nautical miles. Its only limitation was the frequent need to coal.

With war looming ever closer, the German Imperial Admiralty sent Königsberg to German East Africa. Taking command of the ship on April 1, 1914, Fregattenkapitän Max Looff helmed the cruiser into the Mediterranean and through the Suez Canal to its new home port, the colonial capital of Dar es Salaam. Looff’s short-term orders were to patrol coastal East Africa. When war broke out, he was to use his ship to attack and disrupt British shipping around the approaches to the Red Sea, the busiest sea-lane in the world and vital to Britain’s survival.

In late July 1914 Looff returned to Dar es Salaam to coal and reprovision. While in port he rigorously trained his deck crew, engineering department and gunners. Looff intended to be ready when war was declared. He didn’t have long to wait.

With Europe on the brink of war, the Royal Navy ordered three light cruisers—Hyacinth, Pegasus and Astraea—from the Cape of Good Hope Station in South Africa to steam north and bottle up Königsberg in Dar es Salaam. But on July 31 Looff slipped out of port just ahead of his British pursuers and turned north toward the Red Sea.

On August 8, four days after the formal declaration of war, the trio of British cruisers shelled the German wireless station in Dar es Salaam, making communication with Königsberg or the German Imperial Admiralty difficult. To prevent the British ships from entering port, German East Africa Governor Heinrich Schnee ordered a large floating pier to be sunk at the harbor mouth. But that also cut off Königsberg from its home port. The British cruisers had already prevented its collier, Koenig, from leaving Dar es Salaam and purchased all available coal in neighboring Portuguese East Africa.

With few options, Looff resorted to raiding the shipping lanes for coal-bearing ships. On August 6 Königsberg stopped the British freighter City of Winchester, from which Looff’s crew transferred more than a thousand tons of coal before scuttling the freighter. Meanwhile, the German steamer Somali, which had managed to slip out of Dar es Salaam on the night of August 3–4, was also steaming to resupply Königsberg with coal. By the time the ships rendezvoused 10 days later, Looff’s cruiser was down to 15 tons of coal. Somali loaded more than 900 tons aboard Königsberg, enough for about four days of steaming. On August 23 Somali again supplied the cruiser with coal.

By early September Königsberg’s engines desperately needed an overhaul. Cut off from friendly ports, Looff had a refuge in mind. The largest river in German East Africa was the Rufiji (in present-day Tanzania). Navigable for some 60 miles and flanked by the largest mangrove forest in East Africa, the river offered many places for a ship to hide while undergoing repairs. Its delta spans more than 100 miles of coastline, while just offshore lies 170-square-mile Mafia Island. Looff decided to move up the Rufiji’s north channel to find a mooring. On September 3, led by one of its launches, Königsberg moved slowly into the thickly wooded and swampy delta. The late summer air was as hot and humid as a sauna. Looff stationed two of his three launches 6 miles upriver at wedge-shaped Salale Island. There he mounted two of his 4.1-inch guns, set up searchlights and ran telegraph lines from the island to Königsberg to give Looff ample warning of any approaching enemy ships.

Somali’s captain had arranged for small coastal tugs to resupply Königsberg and got word to Looff that HMS Pegasus, which had nearly caught the German cruiser at Dar es Salaam, was patrolling the East African coast. Königsberg’s captain realized the British light cruiser would have to coal at least once a week, and German spotters soon reported the presence of the British warship at Zanzibar, an island some 100 miles up the coast. A onetime pirate haven, the British protectorate was a busy port for Arab dhows and small ships. Looff decided to take the chance to eliminate one of his adversaries.

Pegasus was in the midst of coaling from a barge at Zanzibar early on Sunday morning, September 20, its engines shut down, when Königsberg hove into view at the harbor entrance. There was no time for the British crew to react. At 0525 hours Königsberg opened fire from 9,000 yards, its shells soon hitting home. The so-called Battle of Zanzibar did not last long. At 0555 Looff and his officers watched as Pegasus, holed more than two dozen times, settled by the bow. As its crew attempted to beach the sinking warship, Pegasus finally capsized and sank with 31 killed and 55 wounded. British gunners hadn’t even managed to hit Königsberg, which remained out of range. After sinking the picket ship Helmuth and dumping several barrels loaded with sand at the harbor entrance to fool the British into thinking they were mines, Königsberg turned about, leaving a curved ostrich feather of white foam.

His greatest threat neutralized, Looff could finally begin repairing his ship’s engines. As Königsberg steamed back up Rufiji’s north channel to its mooring off Salale, joined by the supply ship Somali, the cruiser’s crew sowed real mines in the ships’ wake.

The Royal Navy, infuriated by Königsberg’s hit-and-run attack on the helpless Pegasus, went all out in its efforts to hunt down the German warship. Supplemented with escort destroyers and, at intervals, the old pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Goliath, the squadron was placed under the command of Rear Admiral Herbert King-Hall, commander of the Cape of Good Hope Station. His first order of business was to find Königsberg. The German light cruiser had last been seen steaming from Zanzibar, but more than a month passed before there were any leads. Then, on October 19, one of King-Hall’s light cruisers, Chat-ham, stopped the German steamer Präsident. An examination of its papers revealed Präsident had coaled Königsberg in the Rufiji Delta in recent weeks, though King-Hall reasoned his quarry may since have steamed most anywhere.

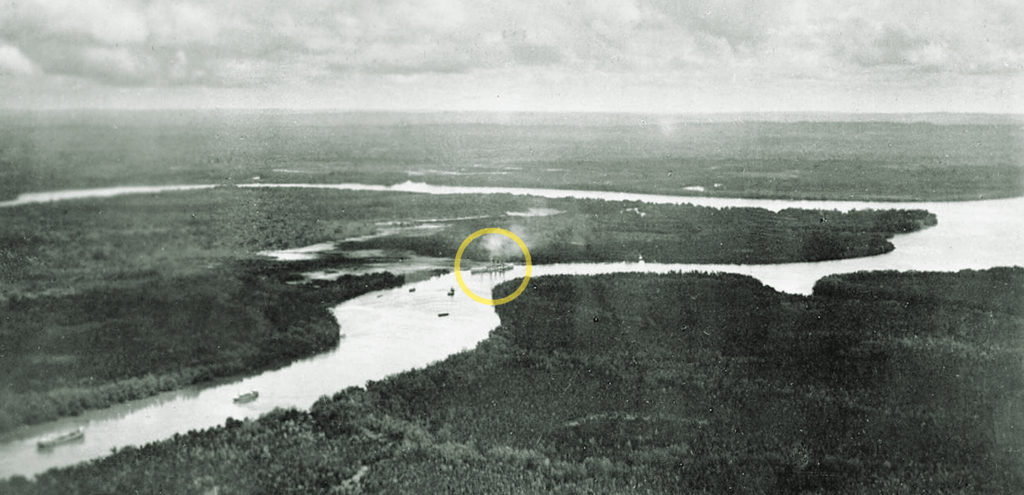

As luck would have it, on October 30 Chatham observed smoke up the Rufiji. That was enough for the admiral. Königsberg and its supply ship Somali were somewhere upriver. But given the hundreds of square miles of channels and mangrove-shrouded islands, King-Hall had no illusions about finding them without an exhaustive search.

First, to ensure Königsberg did not escape, the admiral had Chatham and its sister light cruisers Weymouth and Dartmouth blockade the mouth of the delta. Fortunately for the British, native informers warned them about Looff’s defensive positions, which made any closer approach hazardous.

On November 3 the cruisers tried in vain to blindly shell Königsberg, though four days later Chatham scored a lucky hit on Somali, destroying it. On November 10 Chatham and four smaller ships managed under fire to scuttle the collier Newbridge in the main channel, hoping to prevent Königsberg’s escape. Later that month the newly arrived Goliath also sought to damage the German cruiser with blind shelling. But the delta’s water proved too shallow for the battleship to close within range, even with its big 12-inch guns. The shelling only convinced Looff to move Königsberg 5 miles farther up the papyrus- and mangrove-choked river.

At that point King-Hall tried a different tack. That fall he’d learned of a civilian pilot named Dennis Cutler, who was ferrying passengers around the harbor of Durban, South Africa, in a Curtiss floatplane. Recruiting Cutler into the Royal Naval Air Service at the rank of sublieutenant, King-Hall had pilot and seaplane brought north on the converted armed merchant cruiser Kinfauns Castle to search for Königsberg. Cutler’s first attempt, on October 19, ended with his forced landing after the plane ran short of fuel. Three days later he spotted Königsberg, but as he lacked a compass, he could give only an approximate position. A third flight with an observer yielded better information. Unfortunately, the plane went down in the delta on Cutler’s fourth flight, and he fell into German hands. Further searches by Sopwith and Short seaplanes fared no better.

KÖNIGSBERG

- 3,400 tons

- displacement

- 378 feet

- length

- 43 feet

- beam

- 17.3 feet

- draft

- 24 knots

- speed

- 322 men

- complement

- including 14 officers

- This is an example second line but this one goes to more than one line

- And we have a third line for showcase.

A week before Christmas Looff moved Königsberg one more time. Its final mooring was some 17 miles upriver. There its launch nudged the warship up against the north bank of a narrow channel winding through the thick mangrove forests. Looff sent men ashore to cut branches for camouflage. He then sent a runner north to Dar es Salaam to inform Governor Schnee of his plans. Soon supply lines of wagons pulled by native bearers began rolling down the 120-mile jungle track.

Looff’s engineers dismantled the two reciprocating engines. Floated ashore by barge, they were transported overland to Dar es Salaam for overhaul. Meanwhile, Looff received orders from Lt. Col. Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck to yield up some of his crew in support of the latter’s East African campaign against the British. Looff was able to retain only 220 men, which would leave his ship shorthanded in a battle at sea.

Meanwhile, Königsberg was short on coal and had used up about a third of its main gun ammunition. Malaria, dysentery, malnutrition and heat prostration took their toll on the skeleton crew. Snakes and crocodiles were a constant threat. Time was running out for the cruiser. Looff still needed to install the engines and head downriver, ever closer to the blockading British ships. Then would come a battle with superior forces.

In early January 1915 a frustrated King-Hall resorted to an unconventional means of finding Königsberg.

Enter one of the most colorful characters in South Africa. Philip Jacobus Pretorius, a Boer born in the Transvaal region of South Africa in 1877, was the most famous hunter and guide in sub-Saharan Africa. Although his father had fought the British in the 1899–1902 Second Boer War, he had good relations with the British and hated the Germans almost as much. King-Hall personally invited him to help the Royal Navy find Königsberg.

On receiving the message, Pretorius traveled to Durban, where he was welcomed aboard Goliath, which alternated with Hyacinth as King-Hall’s flagship. The next morning, as the cruiser sailed for the Rufiji Delta, the admiral greeted him cordially. “King-Hall was a charming man, slightly under 6 feet in height, red-complexioned and possessing the bushiest eyebrows I had ever seen,” wrote Pretorius in his autobiography, Jungle Man.

King-Hall asked whether Pretorius, who was familiar with the region from his hunting treks, would be able to move up the Rufiji and pinpoint Königsberg. Pretorius, only too glad to help rid Africa of the seagoing menace-in-being, agreed to help. He would need eight days.

Landed with a radio operator on Mafia Island by a launch from Goliath, Pretorius recruited a half dozen trusted natives. Two days later Weymouth ferried the band to the mainland with a small dugout canoe. After hiding the dugout, the men marched inland and waited along the broad track on which the Germans were moving equipment and provisions. Pretorius soon captured two native porters and convinced them to show him where Königsberg was moored. They took him to a riverside hillock from which he scouted the German cruiser, some 300 yards away. “She was well camouflaged,” Pretorius recalled, “smothered in trees on her deck, and her sides painted so that she seemed part of the surrounding jungle.”

After making careful note of its position, the scout, his men and their prisoners returned east and paddled the dugout back to Mafia, where he signaled, “Pretorius wishes to see the admiral.” Exactly eight days after having left Goliath, he handed his report to King-Hall. The admiral was impressed, but he needed more intelligence. “The locating of the ship was but the preliminary part of my job,” Pretorius recalled. King-Hall wanted to know Königsberg’s exact range from the coast and the state of its armament. Weeks of scouting lay ahead.

Once again Pretorius headed inland to the riverside vantage point. This time using powerful field glasses, he was able to clearly see Königsberg’s decks, counting eight of its 4.1-inch guns still in their mounts. But he could not determine whether its torpedoes were still aboard. Making contact with the friendly chief of one of the villages from which Looff had recruited laborers, Pretorius learned the chief’s son worked as a collier on Königsberg. The chief offered to go to the tent camp set up beside the cruiser and press his son for information. Only half trusting the chief’s intentions, Pretorius said he would join him. Deeply bronzed from decades of being in the sun, with black hair and dark eyes, he decided to pass himself off as an Arab. Clad in suitable clothing and carrying a basket of chickens, Pretorius and the chief (posing as his servant) were stopped short by German pickets. But Pretorius convinced the guards to allow his “servant’s” son to leave the ship and speak briefly with his father. “Where are the long bullets that swim in the water?” the chief asked the boy in his native tongue. The reply proved vital, for the boy said the torpedoes had been transferred to the two launches waiting in the delta. Any British warship attempting to move upriver would be in for a hot reception.

By the time Pretorius returned to Mafia from his second scouting trip, King-Hall had transferred his flag to Hyacinth. (Goliath was sent up to the Dardanelles, where on May 13 it was sunk by a Turkish torpedo boat.) On learning of Königsberg’s torpedo-armed launches, the admiral ordered all ships to remain well out to sea. Meanwhile, at the direction of the British Admiralty, two shallow-draft Humber-class monitors were being towed down from the Mediterranean to join King-Hall’s squadron. Ordered by the Brazilian navy in 1912, the Vickers-built gunboats were purchased by the Royal Navy in August 1914 to add nearshore firepower to the fleet. At just over 1,200 tons displacement and 267 feet long, the monitors looked like nothing else in the Royal Navy. Severn and Mersey boasted a powerful main armament of two 6-inch guns and two 4.7-inch dual-purpose guns for high-angle fire. Drafting less than 6 feet, the monitors would be able to move upriver and shell Königsberg.

Once again sending Pretorius into the breach, King-Hall asked the scout to find a viable channel of approach and a suitable range point in the delta from which the monitors could fire. By then knowing the delta as well as anyone, Pretorius charted a channel 6 to 7 feet deep that extended 7 miles up the north channel. It ended at a reef within 6-inch gun range of Königsberg. It was an ideal spot, though like the British cruisers and Goliath before them, Severn and Mersey would have to fire blind over hills and mangrove forests to hit their distant target. Pretorius then spent a tedious month tracking the tides.

Finally, on the morning of July 11—after an abortive attempt five days earlier to engage Königsberg—the two monitors, preceded by two minesweepers, moved ponderously up the middle channel of the Rufiji. Pretorius watched the fruits of his long labors from the deck of Hyacinth. “I was watching their slow progress toward that position I had found for them,” he recalled, “[when] then the sea seemed to burst, and a tremendous column of water shot up into the air in front of the flagship, followed by a thunderous roar that filled the world.”

Warned by its telegraph posts on the coast, Königsberg had opened fire. More shells from the unseen German cruiser exploded around the British squadron, followed by several from the two shore-based guns. The British ships answered, loosing salvos in the general direction where Königsberg lay. The monitors held their fire until reaching the range point marked by Pretorius.

Tactical Takeaways

- Get while the getting… Four days before the formal declaration of war Max Looff helmed Königsberg out of Dar es Salaam just ahead of pursuing British ships.

- Be ready for anything. The British light cruiser Pegasus was caught at its mooring in Zanzibar, its engines shut down, when Königsberg came calling and sank its enemy counterpart.

- Don’t fence yourself in. Looff sought a favorable shelter when he sailed up the Rufiji to overhaul his engines, but in so doing, he left himself no avenue of escape.

- This is an example second line but this one goes to more than one line

- And we have a third line for showcase.

Then began the blind duel. “The firing increased,” Pretorius recalled, “and now it burst out from a new quarter in the very heart of the bush. The monitors were in action. Two aeroplanes had appeared over the delta, and I was informed signals were being received from them.” The airborne spotters soon got the British gunners on target.

As Severn and Mersey unleashed their heavy shells on Königsberg, smoke roiled from out of sight upriver. Thanks to Pretorius, the British gunners knew exactly how far away and in what direction the German cruiser lay hidden. Looff was at a serious disadvantage. Moored up against the bank of the narrow channel, he could not maneuver, and his shorthanded crew was unable to load and fire the guns as fast as a full crew. Königsberg took several hits from the heavy 6-inch incendiary rounds, which ignited raging fires on the decks. The trees used for camouflage also caught fire as sailors tried desperately to push them overboard.

For five hours shells rained down on the German cruiser, silencing its guns in turn. Eventually, all return fire ceased, and dense smoke rose from Königsberg’s mooring. Just after 1400 hours King-Hall ordered his ships to cease fire.

Six days later Pretorius and his band found what was left of Königsberg. “One would scarcely have known what she had been,” he recalled. “Beside the bush-crowded edge of the small island against which she had been moored lay little more than a vast disorder of tortured steel, made the more unlovely by broken bodies strewn at every angle.” SMS Königsberg’s reign of destruction had ended. Nineteen of its skeleton crew had been killed, another 45 wounded, including Looff. After scuttling his ship in the shallow river and burying his dead, the captain had the surviving crew salvage all 10 guns for transport to Dar es Salaam. The repaired guns and the ship’s crew went on to serve in East Africa under Lettow-Vorbeck.

With the threat removed, the British squadron resumed escorting convoys, while P.J. Pretorius went back to his scouting and intelligence work. Among the most colorful and storied adventurers in Africa, he died at age 68 on Nov. 24, 1945, weeks after having witnessed the end to yet another war.

A contributor to more than a dozen naval, aviation and military history magazines, Mark Carlson is working on a book about the first six months of the Pacific War. For further reading he recommends Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany and the Winning of the Great War at Sea, by Robert K. Massie, and Jungle Man: The Autobiography of Major P.J. Pretorius.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.