You’ve had success addressing topics people like to think they know: Bunker Hill, the May ower, and now Benedict Arnold. What led you to take this angle, what do you enjoy about it, and what are the challenges?

I developed my approach in my first book, Away Off Shore, about Nantucket Island, and in working on In the Heart of the Sea. I had heard and read the standard accounts, but as I pushed into the source material I realized that it was possible to bring a new and fresh perspective. I’m not a history expert. I’m a curious guy, and I want to know more about things, especially in the primary source material. My angle is to open the hood and look under it and see how things work. That’s what gets me excited, that’s the juice for me.

This can involve harsh perspectives on nationally beloved figures.

Critics might say, “How can you write these things about our forefathers?” but I’m not trying to drag anyone down. I want to show these people in all their complexities, all their humanity, all their provocative behavior. The big challenge in writing narrative nonfiction is to tell the story of the past not only in intellectual terms but also in emotional terms, based on the available evidence. You can’t make it up. I have to identify the arc of the story and identify the gaps in that arc and find ways to write around them, often by invoking similar situations.

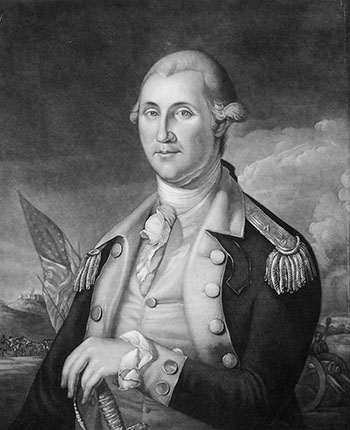

Valiant Ambition contrasts Washington’s self-control and Arnold’s impulsiveness. How do these men illustrate aspects of the American character?

In many ways Washington and Arnold were similar. They both were naturally aggressive, ready to take it to the enemy on the battlefield. Arnold gave in to his passions. Washington had an inner Arnold, but he had learned to control his impulses. He was able to see the larger world beyond his own point of view. Most of us are like Arnold, so self-absorbed that we only see things in terms of our own interests, but Washington had this Apollonian emotional core that enabled him to exercise control over himself. In the face of Arnold’s betrayal, Washington was analytical. He could use his brusqueness to great advantage, saying just enough to someone who was on his wrong side to cause that person to self-destruct. The book begins with Washington down and Arnold up, but at the midpoint there’s a reversal that was fascinating to trace, and as events unfold Washington comes into his own and Arnold comes to grief.

Love of risk gripped Arnold. How did that gure in his treason?

Under duress, Arnold’s impulse always was to act, not to reflect. He always had to do something. And when things were falling apart, with Washington holding the country together, Arnold made the riskiest move of his life—and he almost pulled it off.

The book is dramatic even when you know what’s going to happen.

But in the moment, you don’t know what’s going to happen. History is not fated, and people in the past didn’t know what was going to happen. That’s part of my process—writing as if I don’t know what’s going to happen. When you’re living in the moment, you have no ability to see the future. You only have the information in front of you—which makes Washington’s achievements seem even more remarkable to you.

Assess the role that Benedict Arnold’s wife played in her husband’s undoing.

Peggy Shippen is an underappreciated figure in American history. She is a very interesting character, and she did have a significant role in the plot. She exerted powerful influence on her husband, who is said to have been his own man but who actually was swayed by his staff and certainly by his wife. Peggy came from a loyalist family in Philadelphia; she had many ties to the British. She was half her husband’s age, and she was a forceful personality who, as we can see in the letters between Arnold and John Andre, his British contact, was the conduit for information to the British. I see Peggy Shippen, as I see Arnold and the others, with sympathy; I see where they were coming from. And I see how the dynamic of his marriage to Peggy made it harder for Arnold to act in any other way.

Not a few ther American rebels turned their coats. Why did Benedict Arnold emerge as the iconic traitor of the Revolution?

Throughout his career, he had such air, such style, and he always went for the drama. The histrionics going

on in the Hudson Highlands—midnight meetings with Andre, the way Arnold held things together when he learned that Andre had been captured—are so over the top. And because Arnold had been so revered for his record as the American Hannibal, for him to go over to the enemy was inconceivable, so it’s no surprise that he became the American traitor of all time.

As Iago is more interesting than Othello, Arnold is more interesting than Washington. Why?

We know more about Arnold. We have such a complete record of Arnold through his letters, but we have hardly any of the “unbuttoned” Washington; his letters to Martha, for example, are lost. Washington managed his life so completely that he exists mainly in public; there are a few private letters, such as to Lafayette, but otherwise Washington is a multifaceted figure for whom we lack certain key facets. Arnold and his passions, his drama, his conflicts—they are all right there.

In what ways did Arnold change Washington?

Washington always knew Arnold’s limitations. But he never expected treachery from Arnold. After the plot is foiled, Washington writes to Lafayette, “Whom can we trust now?” Until Arnold’s traitorousness came to light, the decline of the American circumstance was systemic. Now it had a face, and that face was Benedict Arnold. Washington still kept the long view, but he also tried to capture Arnold. He was working on several levels, both overt and covert. Washington played a very deep, complex game, and people often underestimated him.

What does it say about George Washington that he would not tell the British spy John Andre he would be executed by hanging?

In the drama surrounding Andre’s trial and death sentence for spying, Washington came under constant pressure from his subordinates. They all were trying to save Andre, who was angling to get off and had charmed them into taking his side. Washington almost lost Alexander Hamilton over Andre, but he knew that he had to be unyielding and that what was needed in the moment was coldly forceful leadership.

Your next book is about the Southern Campaign of the Revolution?

The Southern Campaign will be in there, but I’m focusing on how we won the war at sea off Yorktown. I’m researching the naval battle at Yorktown that decided the fate of the Revolution. What with my maritime back- ground, it’s going to be fun to tie up the threads of what I’ve been writing. And a lot of Americans don’t know that we won our independence through a naval battle between the French and the British.

What was it like to have Hollywood make your earlier book, In the Heart of the Sea, into a movie? What a sideshow! You write a book in isolation, but when someone makes a movie, there are scriptwriters, there are people making costumes, there’s a production team, set builders. It was something completely different. I had the great pleasure of working with Ron Howard, who’s a wonderful director. My wife and I went to the set in England that reproduced the Nantucket waterfront.

I got to play a Quaker. It was an opportunity to witness an extraordinary process, and the result was a movie that brought the book a whole new audience. I’ve heard history buffs get upset about the liberties that filmmakers take, but after seeing In the Heart of the Sea being made I have a lot more sympathy for the compromises that producers and directors have to make to get a film to work. In the end, the exposure generated by the film drives people to the book, and that’s a good thing.

Charles Rappleye is an investigative journalist and editor who has wri en extensively about the media, law enforcement, and organized crime. His latest book is Herbert Hoover in the White House: The Ordeal of the Presidency, Simon and Schuster, $32.50.