Known for waterfalls, gorges, and Cornell University, Cayuga locale was perfect for silent movie ‘cliffhangers’

Harry Isaacs, dressed as an Aztec chieftain, teetered on the cliff edge, staring down at Triphammer Falls. The cascading waters filled a pool 50 feet below, creating clouds of vapor. The compact man of 70 bent his knees, clapped his hands together over his head, and executed a flawless dive. The Shanghai Man, a film being produced by Leopold and Theodore Wharton, centered around Aztecs, but the nearest Indians to Ithaca, New York, the producers could find were on the Onondaga reservation, Harry’s home, near Syracuse. In July 1914, 40 men and ten women from the reservation traveled 60 miles by special train to the Wharton studios in Ithaca where, their ranks augmented by a few rouged Cornell boys, they played angry Mesoamericans.

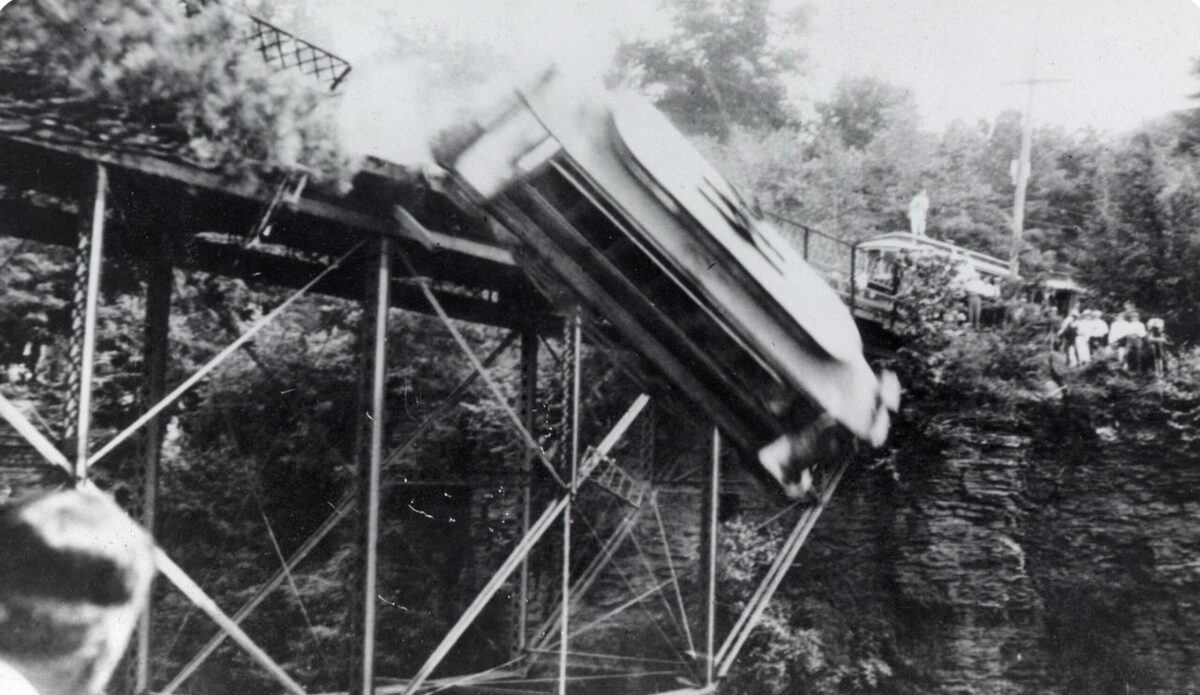

Harry’s gambit paled next to another stunt staged that summer for The Prince of India, originally titled Kiss of Blood. This time, the Wharton crew jettisoned a trolley car off Ithaca’s Stewart Avenue bridge. The rig plunged 100 feet before smashing against the rocks of Fall Creek gorge. Nearly 1,000 onlookers watched in delighted horror. The dive and the crash illustrate why the Wharton brothers came to Ithaca to make movies. Rife with stunning topography—dozens of gorges and hundreds of waterfalls, cascades, and cataracts—Ithaca lent itself to the “cliff-hanger” genre popular at the time. Ted and Leo wove a glamorous tapestry around the town of 16,000 residents.

The brothers convinced themselves Ithaca had a cinematic date with destiny. Beguiled locals responded by providing props, background actors, craftsmen, credit, and enthusiasm. The spell worked—for a while.

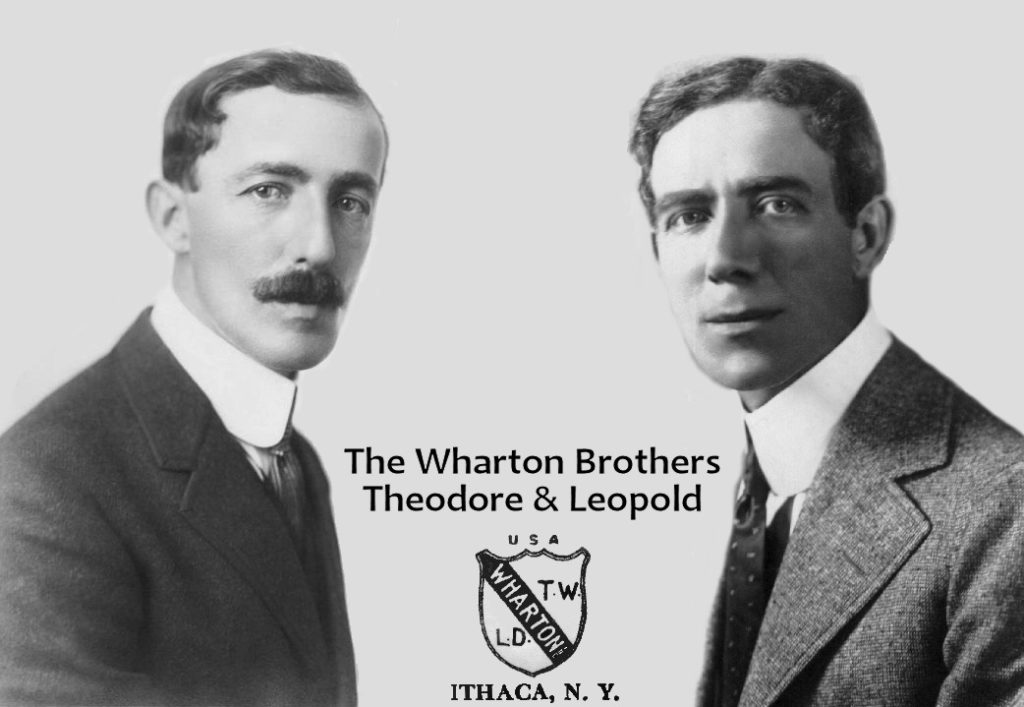

Show-biz journeymen who started in live theater in the 1890s, Leopold and Theodore Wharton could do it all: act, direct, write, produce, build sets, stage-manage. Leo was born in Manchester, England, in 1870. When Ted arrived in 1875, the family had moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. The Whartons went on to Texas, where the boys spent their youth. Like so many men in the fledgling cinema trade, Ted and Leo began their careers in live-theater companies. After 15 years, Ted migrated into motion pictures in 1907 writing “scenarios,” as early screenplays were called. After buying 28 of his first 30 scripts, Edison Studios hired him as a scenario editor and studio supervisor.

When Pathé Freres assembled an American venture in Jersey City, New Jersey, that studio’s first director was Ted Wharton. He moved on to Chicago-based Essanay Film Manufacturing in 1911. Essanay gave Ted his first opportunity to film in Ithaca. It was love at first sight.

On the southern edge of Cayuga Lake, Ithaca then, as now, was known as the home of Cornell University, the Ivy League institution on the east side of town. Cornell’s football team, the Big Red, first lured Ted and his camera. In October 1912, he filmed a Big Red home game against Penn State. Essanay marketed the footage as a one-reeler, Football Days at Cornell, touted as the first-ever live-action motion picture of an American college sports event. Ted Wharton saw in Ithaca a wealth of locations suited to nail-biting serial “photoplays” gaining popularity—not only natural settings but 19th-century streets and storefronts, for backgrounds and b-roll, as well as a supply of agreeable extras. Wharton pitched the town to his boss, George K. Spoor, who agreed to send him back with a field production unit the following spring.

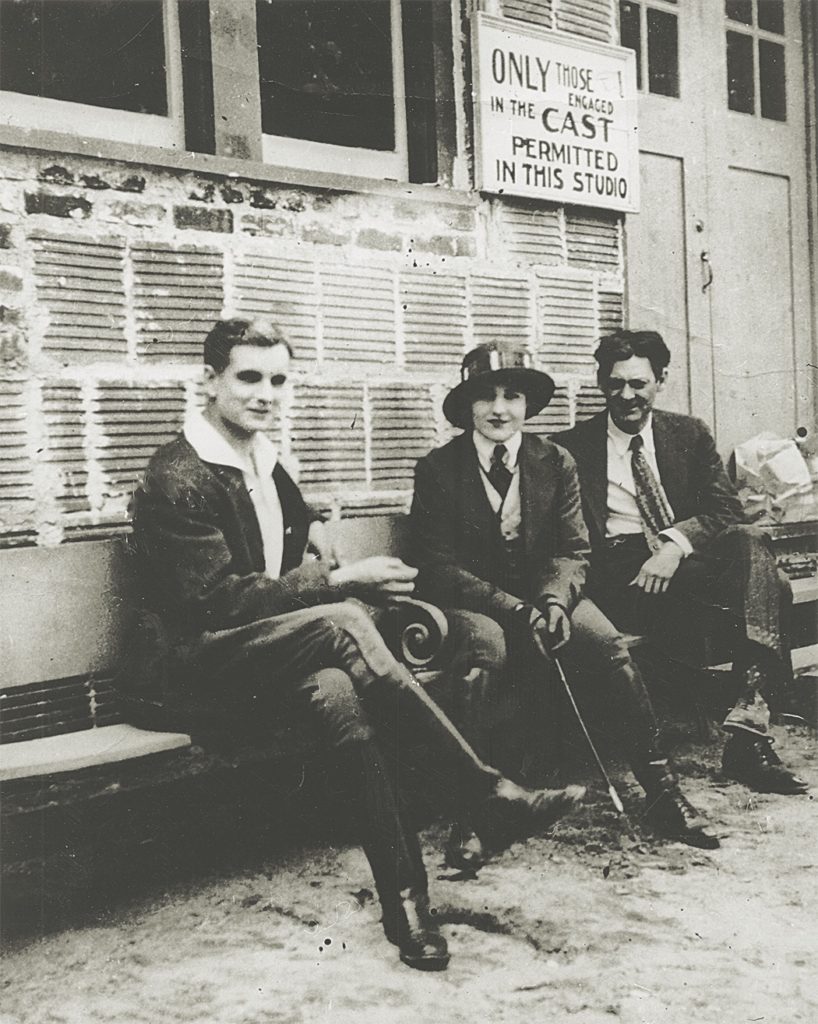

The Ithaca Journal reported on May 15, 1913, that matinee idol and Essanay star Francis X. Bushman, he of 61 film credits, had registered at the Ithaca Hotel. Bushman’s hotel stay was brief; Spoor rented his star a large, two-story house just off the Cornell campus. Bushman, with his wife and children, occupied the first floor. The upper story was converted into dressing rooms for cast members.

Ted Wharton checked in June 1. Handsome, lean, and energetic, with dark hair and piercing eyes to match, mustachioed Ted brimmed with story and staging ideas for Bushman and fellow actors William Bailey, Frank Dayton, John Breslin, Helen Dunbar, Juanita Delmorez, and Beverly Bayne—Bushman’s preferred leading lady and rumored paramour. Wharton’s assistant producer and director was Archer MacMacken. David Hargen handled camerawork. Essanay East was in business. For a studio, Wharton constructed a roofless outdoor stage in the rented residence’s side yard. Muslin above the platform filtered sunlight to create a set on which to stage and shoot “exterior-interiors” without artificial lighting. To process dailies, Wharton had to ship canisters of exposed film to Chicago. Once back in Ithaca, reels were screened and cut apart for editing.

That June 5, the Journal reported that Wharton’s scenic carpenters had built a “picturesque cabin…below the [lower Fall Creek] falls” on a small island at the foot of the cascade. The “picturesque cabin” starred in Wharton’s first Ithaca project, The Hermit of Lonely Gulch, a two-reeler starring Bushman and Bayne. Shooting began on July 11 and wrapped in four days.

Essanay East ground out “photoplays” at a frenetic pace. By July, The Way Perilous, directed by MacMacken—and set in Fall Creek gorge—was finished. Despite the gorge’s visual allure, Wharton cut away to other locations. His script For Old Times’ Sake had Hargen hand-cranking the camera inside a Cornell fraternity house.

Townspeople found it mesmerizing to sit in Ithaca theaters and recognize landscapes, structures, faces, even particular pieces of furniture. Equally enthralled, the local press covered everything remotely cinematic. A July 1913 Ithaca Journal story began, “C.J. Evans, an Ithaca young man…working with the Essanay Motion Picture Company had a narrow escape from death on the rocks of Taughannock Gorge…following the scene of an automobile dropped down a cliff.” Evans’s brush with mortality was a rope burn from rappelling the ravine wall to the vehicle’s remains. In mid-August, Pearl White, queen of the cliff-hangers, arrived in a swirl of scandal. A Pathé crew was to shoot footage of her for the wildly popular Perils of Pauline. The scenes run in Episode 13 of the serial in which White, with co-star Crane Wilbur, leaps from a ledge into a deep pool at the base of Ithaca Falls. Gossip and news reports chittered that White not only wore trousers but smoked, drank, swore, and zipped around so fast in a canary-yellow Stutz Bearcat that she landed in court. Apprehended for speeding in Trumansburg, a few miles north of Ithaca, White allegedly stared at the elderly magistrate as he fined her $5. She whipped out a $10 bill. “Keep the change,” White said. “I’m going out of this town a darn sight faster than I came in.”

By late August, the Essanay team had returned to Chicago, having, in less than three months, shot 11 features: The Hermit of Lonely Gulch, The Whip Hand, Sunlight, The Way Perilous, For Old Times’ Sake, Little Ned, A Woman Scorned, The Right of Way, Antoine the Fiddler, The Love Lute of Romany, and Dear Old Girl. Highlights included dropping an auto containing two dummies into a gorge; torching an abandoned sanitarium; filming a local gypsy encampment; and staging a stagecoach robbery. Shortly before filming wrapped up, George Spoor had toured the Ithaca operation, a visit Ithacans interpreted as a sign Essanay would return. This was bolstered when Cornell Alumni News reported that Wharton found “Ithaca is so good a field for production that he is going to buy a lot and build a $20,000 studio and produce plays here the year round.”

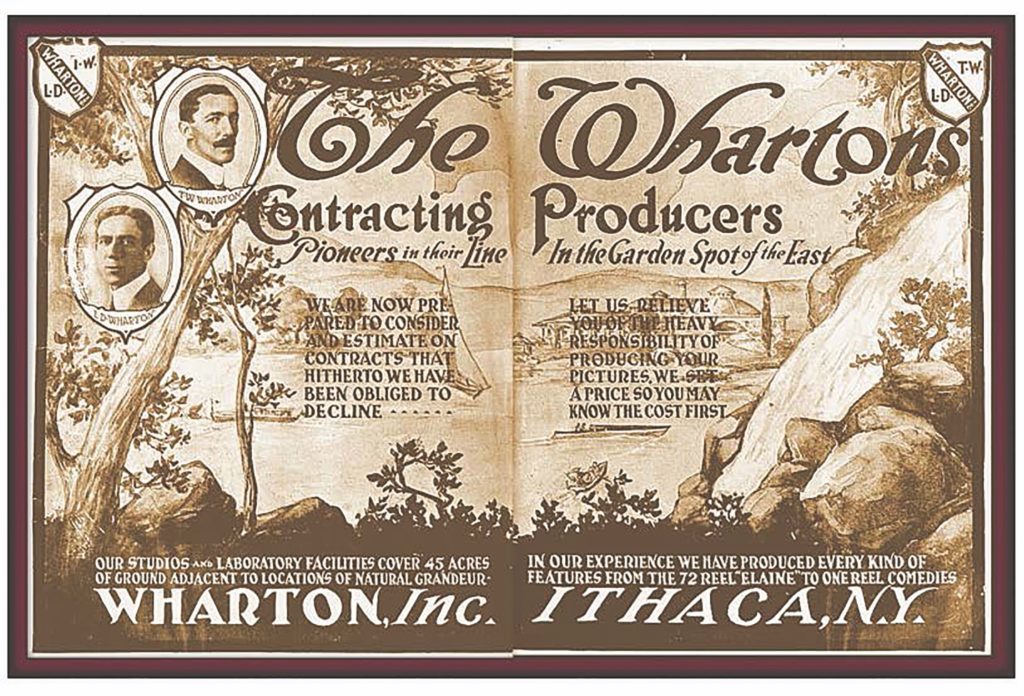

But moneyman Spoor’s interest in making movies waned. Essanay was getting out of cinema. Only Ted Wharton returned to Ithaca in spring 1914—as an independent producer. He convinced brother Leo, on contract as a filmmaker with Pathé, to join him. Ted also recruited his brother-in-law, J. Whitworth Buck, to work the books. Wharton Inc. formed, leased a building on State Street, signed a deal with distributor Pathé Freres, acquired gear, hired crews, wooed investors—including Ithacans—and got the cameras rolling. Ted and Leo produced, wrote, directed and occasionally acted.

The Whartons had accounted for nearly everything but climate. Ithaca shares a latitude with Detroit and Boston. Half the year the ambient temperature is cool, if not frigid. The town averages 64 inches of snow annually—more than twice the national norm—and 154 days of sunshine. “In Ithaca,” the saying goes, “summers are warm and partly cloudy. Winters are freezing and mostly cloudy.” Shooting around the sunlight and temperature deficits was a challenge.

However, Ted Wharton looked past reality, emphasizing that his favorite location had magic. “Ithaca is…a great place and the citizens…cannot do enough for us,” he said in a 1914 interview. “Their good will is a tangible asset…they look upon our company as their own…a rainy day, the businesspeople worry about us. It is…a splendid town.”

Wharton Inc. tore through the 1914 filming season, churning out three- and four-reelers like The Boundary Rider, A Pawn of Fortune, The Stolen Birthright, and The Fireman & the Girl. In New Jersey, the brothers filmed the first 26 episodes of a lucrative serial, The Exploits of Elaine, and its sequel, The New Exploits of Elaine. Pearl White played the heroine.

A spring 1915 Ithaca Journal story reported that Wharton Inc., had relocated all operations to Ithaca’s Renwick Park. The 45-acre expanse, a recreational area and bird sanctuary on the Cayuga Street trolley line, included buildings, forested areas, and 1,200 feet of frontage on Cayuga Lake. The Whartons kept the park, including a miniature train, powered by the world’s smallest steam engine, open to the public.

A more thrilling notice in the paper came that May when Wharton announced the 10-episode finale of the Elaine saga, The Romance of Elaine, would be filming in Ithaca. That summer actors Pearl White, Lionel Barrymore, Creighton Hale, and Paul Everton arrived. Barrymore proved to be a curmudgeon. Spouting dislike for the producers and the location, he holed up in his hotel and left Ithaca as soon as he could.

The Elaine series was popular and profitable. In June 1915, Motion Picture World wrote that Exploits had made Ted Wharton “known in every hamlet in the land…as ’The Man who discovered Ithaca’…through his pictures that beautiful little city has received the finest kind of publicity.” Wharton also hit in 1915 with The New Adventures of J. Rufus Wallingford, a serial whose first five episodes included Oliver Hardy making his uncredited serial debut. He came back in 1916 for another anonymous cameo as chubby maid “Maggie Murphy” in The Lottery Man. That year Wharton released two more popular serials, The Mysteries of Myra and Beatrice Fairfax. The company was on a roll.

In July 1916, Irene Castle waltzed into Ithaca to film the serial Patria. The jingoistic tale of intrigue starred Castle, a famous dancer, as Patricia Channing, heiress turned secret agent, foiling Japanese and other foreign operatives bent on wrecking the American munitions industry. Patria was a coproduction with Hearst International Film Services. With the United States threatening to join the Allies in World War I, pro-German IFS owner and press lord William Randolph Hearst saw in Japan a suitably foreign object for American ire that could take the heat off the Kaiser.

Patria had a solid cast—Warner Oland, adept at playing a variety of ethnic types, Milton Sills, George Majeroni, Dorothy Green, and the well-regarded Castle—and a big price tag. The producers filmed on location in Hollywood, California. Crews built and burned a village of 20 buildings outside Ithaca. The production team staged expensive, crowd-pleasing stunts like Castle speeding across railroad tracks just ahead of an oncoming freight train and dumping a car off a boat into Cayuga Lake. To build audience interest, Hearst newspapers serialized the story in print. But Patria drew mixed reviews and soft box office. “The role which [Castle] plays is a Pearl White part with Douglas Fairbanks trimmings, and she plays it with a mixture of daintiness and fearlessness which is fascinating,” the New York Telegraph wrote.

Japanese diplomats complained to President Woodrow Wilson about the picture’s racist skew. Wilson wanted to keep Japan from allying with Germany. After screening a few episodes, he demanded Hearst pull Patria from theaters. Hearst complied. Patria underwent doctoring. The villains became Mexicans. But Hearst walked out, stymieing hopes for a much-needed re-release. Wharton Inc. was stuck. In January 1917, business manager J. Whitworth Buck quit and left Ithaca. Wharton Inc., its agreements with IFS and Pathé unraveling, announced it would start its own film distribution service.

In April 1917, as the United States was entering the Great War, Wharton Inc. was readying productions for summer and fall, including another serial, The Eagle’s Eye. Filmed in Ithaca and completed that November, the 20-episode series—each episode a two-reeler—was based on the true story of a German spy ring in the United States. Crime expert Courtney Riley Cooper wrote the script and a print serialization for Photoplay magazine. The Eagle’s Eye, starring the well-known King Baggot and Marguerite Snow, showcased everything Ted Wharton loved about Ithaca. Locals Ray June and Levi Bacon did the camera work. Ithacans stepped up as extras. Cayuga Lake masqueraded as the Atlantic Ocean for a re-enactment of the Lusitania sinking. Wharton even capitalized on the weather, staging skating and tobogganing scenes at Cornell. But at $400,000, the true-life spy story was a very costly venture.

Eagle’s Eye premiered in March 1918 as a global flu pandemic was emptying theaters. With the war’s November 1918 end, martial themes were passé. A major theater chain with multiple screens around the country, claiming the film demonized German Americans, refused to show it. Between Patria and The Eagle’s Eye, Wharton, Inc. was mired in debt.

Ithaca’s Wharton story came to a muddled close. Ted returned to town in 1919. Leo went to Texas and stayed. A news squib claimed, “Whartons Form New Company in San Antonio,” and a notice ballyhooed a new headquarters in Galveston, Texas, but the company made no movies in the Lone Star State. Wharton Inc. subleased its Renwick Park facilities to Grossman Pictures. Ted said he would open a new Wharton studio in Ithaca poised for a “full season of motion picture production.” He rented and renovated a building. He completed several episodes of a new serial, The Crooked Dagger. Pathé agreed to pick up the series—and then backed out. The Crooked Dagger was never released. Wharton Studios was finished. In March 1920, a court issued a $6,000 foreclosure judgment against Theodore Wharton. Forced sale of his gear netted $12,000. Ted pulled up stakes for California. He and Leo stayed in movies although they never collaborated again, and neither matched the success of their Ithaca years.

Ithaca’s time as a movie hub ended in 1920, the town remained home to an archive of Wharton movies. The prints, on volatile nitrate-based film, were stored in a shed owned by a local lawyer.

In 1929, the cache of film spontaneously combusted, consuming the oeuvre of the Wharton brothers, who had created a world of cinematic dreams beside Cayuga’s waters.