I have been writing this column for years, and if your attention hasn’t drifted, you probably know that I am not that fond of war movies. I say it every year at this time. Don’t like them, don’t watch them, don’t care to discuss them

And then I turn around and write yet another column about war movies! Am I a hypocrite? Maybe. But it might be more correct simply to plead nolo contendre, “no contest.” You’re an adult, you’re conscious, you live in America: chances are you see a war movie or two. This Christmas, sitting around with “the fam”—my wife and daughters who are visiting us from various parts of the country—I saw two movies dealing with World War II, one about the start and one about the end.

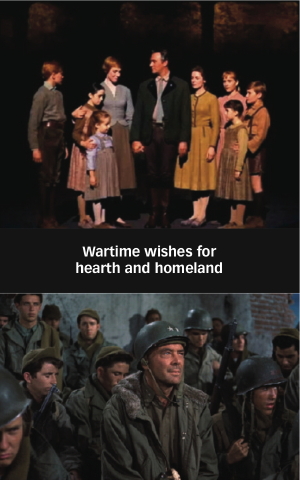

It is easy enough to make light of The Sound of Music. It is so earnest. The lovely Julie Andrews as a governess. Christopher Plummer’s widower Captain Von Trapp. A blended family that can harmonize like pros at the drop of a hat. The Songs! The Alps! The hills are alive!

It’s corny, sure, but when I watched this movie on ABC tonight, it struck me as pretty serious stuff. Even this relatively simple musical has some big themes. Nazi terror. Personal danger. The Anschluss. Indeed, at one point, Captain Von Trapp sings the haunting air “Edelweiss,” defending the independence of Austria and defying the notion of a Nazi takeover of his native land. “Bless my homeland forever,” Plummer sings. He begins to weep as he sings the song, and he cannot continue. Andrews joins in to assist him, and eventually so does the audience.

It is a powerful scene, however jaded you might be. It expresses a basic truth. No one wants to be oppressed by anyone. Freedom is a right, and the urge to live free is a universal one. Damn straight, I thought. Suddenly, The Sound of Music didn’t seem so trivial. Sure, I realized, there were millions of Germans (and Austrians) who supported Hitler, but there were also a sizable number who didn’t, and their voices need to be part of the narrative we tell.

It is a powerful scene, however jaded you might be. It expresses a basic truth. No one wants to be oppressed by anyone. Freedom is a right, and the urge to live free is a universal one. Damn straight, I thought. Suddenly, The Sound of Music didn’t seem so trivial. Sure, I realized, there were millions of Germans (and Austrians) who supported Hitler, but there were also a sizable number who didn’t, and their voices need to be part of the narrative we tell.

It is equally easy to scoff at the entire notion of White Christmas. Bing, Danny, and the “Haynes Sisters” all add up to an amazing musical, sure. The dance sequence with Danny Kaye and Vera Ellen (“The Best Things Happen When You’re Dancing”) is absolutely exquisite, one of the greatest ever filmed.

But the plot… that’s another story. The narrative of General Waverly (ably performed by Dean Jagger) and his failed ski resort in Pine Tree, Vermont, seems like a classic example of “who cares?” Hundreds of thousands of Americans—and millions of men worldwide—died in World War II. Many millions more had their lives shattered: horrible injuries to body and mind and spirit that would never heal. The ripple effects among loved ones, parents and wives and children, were equally tragic. As I’ve written here many times, no one should ever romanticize World War II. Those who fought it paid some heavy dues, and the bill kept coming due for the rest of their lives. So it isn’t snowing? Who cares?

But even here, there were moments in the film that made me reconsider taking such a hard line. That scene early on where the men of the “151st Division” (and I’ll bet that General George C. Marshall WISHED there were 151 divisions in the U.S. Army!) are gathered for their Christmas show is a case in point. The setting is Europe, and presumably the Ardennes, in December 1944. Bing, looking a little old to be a captain in the wartime U.S. Army, sings the men the classic title tune. “May your days be merry and bright, and may all your Christmases be white.” The soldiers are young—far too young to be facing death. They are silent. Some stare off into space. Some lean on their rifles, clearly moved.

Schmalz? Of course it is! Hollywood has sold schmalz to the world for a century now, at a very tidy profit. But even a silly Hollywood film can touch a basic truth. In World War II, a lot of men on all sides spent Christmas of 1944 wishing that they were somewhere else. Somewhere far, far away. Somewhere called home.

We can take the same broad view about the rest of the film. Forget about the general and his ski resort. He’s not the first guy who made a bad business investment! Let us call to mind all those men (and not a few women) who gave up the best years of their lives to fight this horrible war. They did their duty, they fought, and they suffered. Some were brave and some were cowards, some had their bodies broken and some saw their best friends die. Postwar emotions ran the gamut from pride to shame, from denial to anger. At the end of the day, General Waverly wasn’t exactly unique. A lot of men had trouble fitting back in to peacetime. The more you’d invested in the war, in fact, whether time or emotion or heroism, the harder it was to forget.

It’s the ultimate hokey scene—the General in his old uniform and the men from his now defunct division singing, “We love him, we love him…” But at the end of a war, it’s exactly what society needs to tell those who fought. The ones who charged enemy positions without fear, and the ones who spent entire nights cowering in foxholes waiting for the next shell to blow them to smithereens. War places cruel demands on a chosen few, and the rest of us should, at the very least, try to understand.

It is Christmas Day as I write this… Night, actually. Like any person of good will, I have a single wish for all of humankind: let us have peace.