In a Quentin Tarantino-esque series, creator David Weil — whose maternal grandparents were Holocaust survivors — seeks to shock, awe, horrify, and inform audiences in his new Amazon show Hunters. Claimed to be based on true events, Logan Lerman (of The Perks of Being a Wallflower and Fury fame), plays Jonah Heidelbaum a 19-year-old set on revenge after the murder of his Auschwitz-surviving grandmother. He joins Meyer Offerman, played by Al Pacino, and his secret group of Nazi hunters whose sole mission is to kill those seeking to create the Fourth Reich in America. While critics are split on series with its seemingly gratuitous violence, grappling with the moral quandaries of vigilante murder, and the almost outlandish 1970s tropes; the show does bring to the forefront the truth that thousands of Nazis did, in fact, live in the United States — and that many Holocaust survivors would spend the rest of their lives tracking them down.

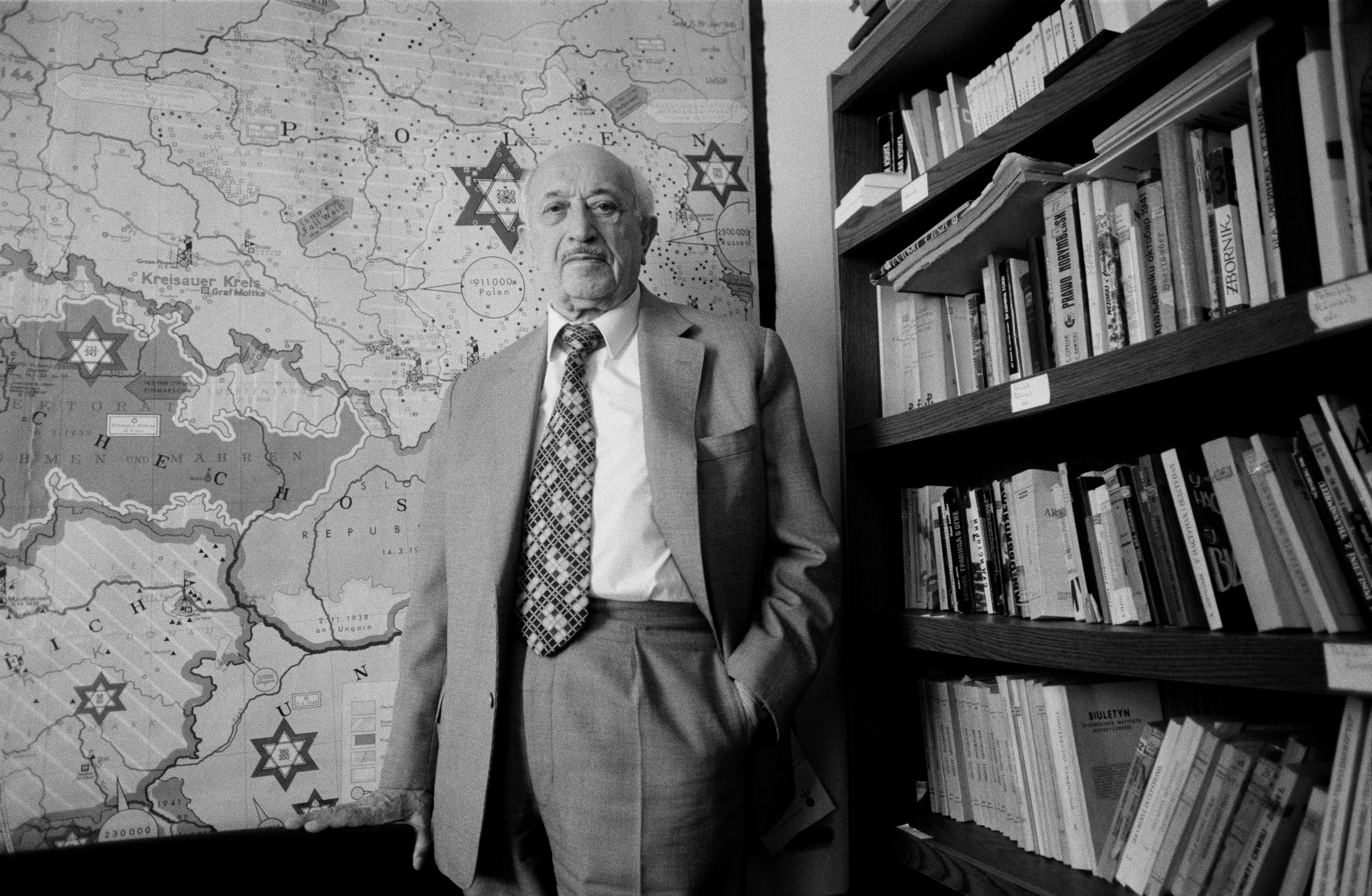

Hunters, however, is built around mostly fictional characters and largely leaves real-life heroes unexplored. The most well-known among them, Holocaust survivor and Nazi hunter Simon Wiesenthal, does make an appearance in a later episode of the show.

After surviving Mauthausen death camp in Austria, Wiesenthal spent more than 50 years hunting down war criminals. Through his work, some 1,100 Nazi war criminals were tracked down and brought to justice. Those of a higher profile include Franz Stangl, the commandant of the Sobibor and Treblinka killing centers; and Karl Silberbauer, the Gestapo agent who led to the arrest of teen Anne Frank and her family. Anne’s diary, published posthumously by the sole surviving member of her family, her father Otto Frank, gave voice to Holocaust victims and whose legacy continues today.

“When history looks back I want people to know the Nazis weren’t able to kill millions of people and get away with it,” said the Ukrainian-born Wiesenthal.

In a 1967 New York Times article, Wiesenthal denies revenge as his motive, seeing his actions as educational. “The schools would fail through their silence, the church through their forgiveness and the home through the denials or the silence of parents.”

Unlike the Nazi hunters in the series, Wiesenthal emphasized “justice, not vengeance.” With Rabbi Marvin Hier calling him “the conscience of the Holocaust.”

Less known, but equally influential, was Fritz Bauer— Germany’s first Nazi hunter. Bauer, who was secretly gay, grew up in a middle-class Jewish family, and in 1930 became Germany’s youngest judge at the age of 27. With Hitler’s ascent to power in 1933, Bauer became a fiery and outspoken critic of the then-chancellor and was sent to a concentration camp for dissidents. Following his release nine months later, Bauer fled to Denmark and would spend the duration of the war there.

Returning to what was then West Germany in 1949, Bauer became a dogged state prosecutor intent on seeking justice for the victims the Holocaust. He became the first German-born citizen to try 22 members of the Nazi SS in the 1963 Frankfurt Auschwitz trials. Only six of the accused were given life sentences and 12 others given terms of up to 14 years, which Bauer believed to be his failure. To him, he would later write, the trial reinforced a “wishful fantasy that there were only a few people with responsibility…and the rest were merely terrorized, violated hangers-on, compelled to do things completely contrary to their true nature.”

Yet the information uncovered and released during the subsequent litigation ensured that the German people could not hide nor forget the horrific killing machine that was Auschwitz.

Not made public until after his death, was Bauer’s crucial involvement in the capture of Adolf Eichmann, one of the major architects of the Holocaust. It was Bauer who received the message from Lothar Hermann that Eichmann was hiding out in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Through Bauer’s tip to Mossad, the high ranking Nazi official was famously captured by the Israelis and put on trial.

Like Wiesenthal and Bauer, Nazi hunters were made up of a network of individuals across the globe seeking to track down those who had slipped through the cracks of justice.

In the United States, however, due to the volume of Nazi émigrés, an entire organization was required.

The Office of Special Investigations (OSI), created in 1979, sought to identify and seek removal of only those who assisted the Nazis and their allies in the persecution of civilians. Early estimates from OSI, often referred to as the government’s “Nazi-hunting” organization, purported that nearly 10,000 Nazis emigrated to the United States after World War II.

The organization was meant to help sift through the mighty caseload. The task however, was monumental.

Witness memories were fallible. Those who survived the Holocaust oftentimes never knew the names of their torturers. And a large majority of witnesses never survived the war.

With more than 600,000 émigrés entering the United States between 1948 and 1953, Nazis, and those who had assisted them, slipped by overworked consular officials reviewing their paperwork. That number included the nearly 1,600 German scientists and engineers who were “imported” to the U.S. as “intellectual reparations” owed to the U.S. and the U.K. in Operation Paperclip.

Wernher von Braun, the famous architect of the V-2 rocket that rained terror down on the streets of London was also a participant in Paperclip, and later served as one of the chief engineers for America’s first space satellite Explorer I.

Arthur Rudolf, another of Germany’s top rocket program specialists, supervised the Mittel-Bau-Dora concentration camp and the brutal slave labor it required to assemble the rockets. An estimated 20,000 inmates perished while tunneling and digging into the mountains around the camp in Nordhausen, Thunringia, Germany.

Rudolf, a U.S. Army interrogator’s assessment read, was “One hundred percent Nazi, dangerous type, security threat….Suggest internment.” Despite this, Rudolph was relocated to the United States and eventually became the project director for NASA’s Saturn V rocket program, which helped put Americans on the moon.

Operation Paperclip was largely hushed up, its characters, like other Nazis in the U.S., under most American’s radar until the beginning of the 1960s and 1970s.

The 1964 high-profile case and subsequent arrest of Hermine Braunsteiner Ryan — a former warden at Majdanek and Ravensbrück concentration camps and then-housewife in Queens, New York — brought the issue to the fore. Known to her victims as “the mare” for her sadistic inclination to kick inmates with her iron-tipped boots, Ryan had previously been convicted by an Austrian court on charges of assassination, infanticide, and manslaughter. She served three years before her release in 1950, entering the U.S. in 1959 and becoming a citizen in 1963.

It was later discovered that Mrs. Ryan had concealed her criminal conviction to American authorities, and in 1971 she was stripped of her citizenship and stood trial in Düsseldorf in 1975.

It was not until the 1970s, however, that the general public became fully alerted to the presence of Nazis living in America. Congressional hearings in 1974, 1977, and 1978 were held to correct this oversight. New York City Congresswoman Elizabeth Holtzman, a member of the subcommittee, was appalled by the issue and largely pushed for the creation of OSI.

For the next 31 years, OSI operated as a branch of the Criminal Division of the U.S. Department of Justice. In March 2010, OSI merged, writes the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “with a new Department of Justice section, the Human Rights and Special Prosecutions Section, while continuing with its original mandate.” There is no statute of limitations on civil immigration and naturalization fraud claims, and to date OSI has successfully initiated the removal of more than 100 Nazis from the U.S. and has blocked more than 200 individuals suspected of Nazi activity from entry into the country.

Through the efforts of OSI, Rudolf, after a successful career at NASA, was linked to Mittelbau-Dora and in a deal to avoid prosecution, renounced his U.S. citizenship.

While there are few Nazi suspects still alive to be charged for their crimes, the hunt for perpetrators continues. Since 2013 there have been 23 charges pending against individuals with connections to the Holocaust, with charges filed as late as October 2019 against former SS guard Bruno Dey.

While Hollywood offers up a splashy alternate reality in Hunters, the true Nazi hunting heroes — the ones who quietly and determinedly stalked down pure evil — deserve recognition.

“When we come to the other world and meet the millions of Jews who died in the camps and they ask us, ‘What have you done?,’ there will be many answers,” Wiesenthal told the New York Times. One will say, “ ‘I have smuggled coffee and American cigarettes,’ another will say, ‘I built houses,’ but I will say, ‘I didn’t forget you.’ ”