At the turn of the 20th century, Vienna, capital of the vast but ailing Austro-Hungarian Empire, reflected on its past with pride and its future with uncertainty. The empire had nurtured Beethoven, Brahms, and Strauss. The city was home to Sigmund Freud, and considered a world leader in science, philosophy, and research. With 2 million inhabitants, Vienna was one of the most populous and multi-ethnic cities on earth, a melting pot of immigrants from across the empire.

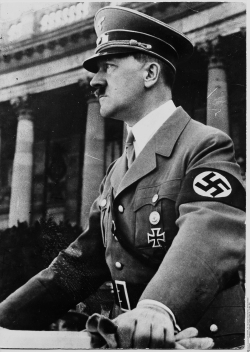

But Vienna seethed with provincial nationalism, socialist ideals, and an odious wave of anti-Semitism. Though its culture and science still predominate, modern Vienna is, of course, a very different place. In the old town section, the Innere Stadt, throngs of tourists fill the streets, lost in reveries over their fabulous surroundings. But I had come to see another side of the city’s history. For Vienna also nurtured the young Adolf Hitler, and, after his rise to power, played a significant part in supporting the Nazi reign of terror. Vienna is rife with reminders of those dark years.

Hitler, together with his friend August Kubizek, moved to Vienna from their hometown, Linz, in 1908. Then 18 and an aspiring artist, Hitler wanted to study at the Academy of Fine Arts at Schillerplatz. Kubizek would study music. They shared a room at Stumpergasse 29, on a street near the Westbahnhof train station. It was an easy walk down bustling Mariahilfer Strasse, which remains the city’s main shopping street, to the academy.

Hitler and Kubizek strolled the Ringstrasse, a three-mile-long boulevard that replaced the city’s obsolete defensive wall, demolished in 1858. The Ring became one of Europe’s great boulevards, lined with an eclectic mix of classical and modern architecture. The two friends admired the Hofburg Palace, which fills much of the southwestern quarter of the Innere Stadt, and the Neoclassical parliament building. Hitler attended parliamentary debates, and in Mein Kampf he claims it was here that he began to loathe democracy. And standing in the cheap seats at the Court Opera, now known as the State Opera, Hitler and Kubizek in-dulged their passion for Wagner. Little has changed. There is perhaps more traffic, but it is still an easy walk through the Innere Stadt to the Ring.

One day Kubizek returned to their room to find that Hitler had left. While Kubizek had been accepted into music school, the academy twice rejected Hitler, which he never told his friend. They would not meet again until 1938.

Hitler moved into a succession of dreary lodgings and homeless shelters, eating in soup kitchens. By 1909 his money—a pension from his mother’s death and family loans—had run out. Occasionally he stayed at the shelter in Meidling, a quiet, leafy suburb some distance south of Westbahnhof. He was already peddling watercolors of Vienna, often to Jewish buyers, when fellow shelter resident Reinhold Hanisch offered to be his agent. Their business flourished, until Hitler accused Hanisch in court in 1910 of withholding payments for a painting he had made of the parliament building. Then, to escape Austrian military conscription, Hitler fled to Munich in 1913. While in Vienna he had spent a great deal of time reading right-wing and pan-German writings, expounding on their virtues to all who would listen; he left Vienna thoroughly anti-democratic and with ideas of a Greater German nation.

There are no plaques in Vienna marking the places where the young Hitler lived. But set in the sidewalk of Mariahilfer Strasse at the top of Stumpergasse, where Hitler and Kubizek rented their room, busy shoppers now walk over small brass markers with the names and dates of individuals sent to their deaths by the Nazis, placed at their last known residences or workplaces. There are more set in the sidewalks of the streets nearby, but you need eagle eyes to spot them while walking. German artist Gunter Demnig has placed over 22,000 of these Stolpersteine, stumble stones, in towns and cities across the former Third Reich.

Adolf Hitler triumphantly returned to Vienna in 1938 following his Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria. His parade progressed along the boulevard, passing the dissolved parliament and the town hall before stopping at the Hofburg Palace, where the emperor once lived. From the terrace of the Neue Berg wing, he welcomed to the Reich the 200,000 jubilant Viennese gathered before him in the Heldenplatz. Hitler spent just 24 hours in Vienna before returning to Berlin. Vienna had become a provincial capital.

Adolf Hitler triumphantly returned to Vienna in 1938 following his Anschluss, the German annexation of Austria. His parade progressed along the boulevard, passing the dissolved parliament and the town hall before stopping at the Hofburg Palace, where the emperor once lived. From the terrace of the Neue Berg wing, he welcomed to the Reich the 200,000 jubilant Viennese gathered before him in the Heldenplatz. Hitler spent just 24 hours in Vienna before returning to Berlin. Vienna had become a provincial capital.

The Jews of Vienna did not participate in this orgy of adoration. In front of jeering crowds they were forced to scrub the streets, their homes and shops were looted, and thousands were packed off to camps. Today, on Albertinaplatz in the Innere Stadt, there is a poignant sculp-ture of a humiliated, almost formless, scrubbing Jew.The November 1938 Kristallnacht pogrom was particularly vicious here. The City Temple, Vienna’s main synagogue in the Innere Stadt, located in an apartment building on Seitenstettengasse, was the only one of the city’s 94 Jewish places of worship to escape destruction. Nearly 700 Jews were murdered or committed suicide that night.

Adolf Eichmann had already set up his Central Office for Jewish Emigration in Vienna. It was, at first, a simple system of extorting the assets of Jews in return for allowing their emigration. He likened it to a conveyor belt. By 1939, some 130,000 of Vienna’s 206,000 Jews had left the country. With the outbreak of war, further emigration was impossible and Eichmann efficiently organized the deaths of the city’s remaining 65,000 Jews in extermination camps. In Judenplatz, a quiet square removed from Vienna’s tourist bustle, a small and elegant memorial stands in remembrance. Its concrete walls are shaped like an inside-out library of 7,000 identical blank books with spines turned inward, representing the history erased with each Holocaust victim. The entrance doors have no handles. You cannot enter.

The Nazis did not confine their plundering to emigrating and soon-to-be-murdered Jews. Viennese art galleries and private collections were also looted. Auction houses were taken over by the Nazis to sell expropriated art. Ownership of much of this art remains contentious today. Hitler—by the late 1930s immensely wealthy from business largess, royalties from Mein Kampf, and the use of his image on postage stamps—was a major buyer. He purchased Vermeer’s The Art of Painting, extorted from a Viennese family. Valued at $200 million, it now hangs in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum, and is the most valuable painting on display in the city. The seller’s heirs want it back, claiming it was sold under duress.

Fearing the Allies would bomb Vienna, in 1940 Hitler ordered the construction of three pairs of massive concrete flak towers in Arenberg, Esterhazy, and Augarten Parks to defend the city. The larger tower of each pair had massive firepower; the smaller had less and acted as the command center. By 1944, when the towers were completed, Allied bombers were in range of Vienna. Though the towers provided formidable defenses, they were more useful in protecting the 10,000 civilians sheltering in each tower during raids.

A tower in Esterhazy Park has been converted into the Haus des Meeres sea water aquarium, one of Vienna’s top tourist attractions; another in Arenberg stores part of the collection of the Museum of Applied Arts, open to the public every Sunday. They remain some of the largest buildings in Vienna, but, as with Hitler’s former lodgings, there are no plaques to acknowledge their past.