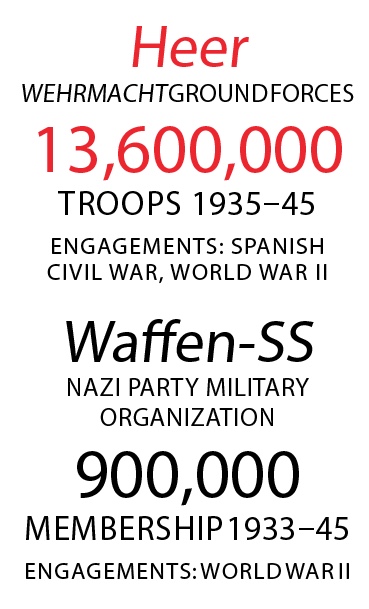

Sprinting toward Belgrade amid the Third Reich’s April 1941 invasion of Yugoslavia, two distinct military formations sought to outrun each other. On one flank was the Heer, the traditional standing army of Germany; on the other the Waffen-SS, the armed paramilitary wing of the Nazi Party.

The upstart latter organization won the race to the Yugoslav capital. Entering with a reconnoitering force of just six men, SS-Hauptsturmführer Fritz Klingenberg of the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich” even managed to bluff his way into capturing the city. Days earlier the Luftwaffe had bombed Belgrade, killing upward of 2,200 civilians. Believing Klingenberg’s threat the city would be subjected to further bombardment by aircraft and heavy artillery, Belgrade’s mayor capitulated. When Heer troops arrived, they were understandably irked, having prepared for a lengthy and complex assault.

It would not be the last time Adolf Hitler’s two armies found themselves competing head to head. In order to understand why the Nazis employed what were essentially two distinct ground armies during the war, one must consider the nature of the Nazi state itself. Despite impressions of Hitler’s German state being one of monolithic centralized control, nothing could be further from the truth. A firm believer in the Darwinian concept of “survival of the fittest,” the Führer actively encouraged competition among the various state and party organs, engendering fierce rivalries—such as that between Heinrich Himmler’s Gestapo (secret police) and Wilhelm Canaris’ Abwehr (military intelligence)—that often resulted in recrimination, betrayal and, in Canaris’ case, execution. It stood to reason, therefore, such duplication of effort would ultimately manifest itself on the battlefield with two ground armies, each possessing its own distinct command structure, ranks, uniforms and training methods.

The German standing army came into being on the heels of unification in 1871. Among the key social and political backbones of the state, it was a proud order dominated by a conservative, largely Prussian officer corps. After World War I, under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the defeated Deutsches Heer was dissolved, and from 1921 to 1935 the renamed Reichsheer (Army of the Realm) was restricted to a total ground force of just 100,000 troops and prohibited from fielding tanks, large-caliber artillery and aircraft.

Generaloberst Hans von Seeckt was tasked with reorganizing the army. Angered by the humiliating constraints imposed by the treaty, he believed another great war was inevitable, and Germany must be prepared for it. Seeckt was especially determined to retain the best officers as the core of any new army. Indeed, many such officers would go on to become famous and/or notorious for their exploits in the forthcoming war, notably Erwin Rommel and Heinz Guderian, the latter the principal architect of blitzkrieg—the sort of highly mobile, combined-arms assault that would prove so effective in World War II.

A true innovator, Seeckt embraced cutting-edge tactics and new technologies, believing speed and daring were the keys to victory. He found a kindred military spirit in the then ascendant Hitler, who’d served in the trenches in World War I and despised the officer class and outmoded military traditions. For such reasons wartime general and postwar German President Paul von Hindenburg privately derided the Austrian-born Hitler as “that Bohemian corporal.” On Hindenburg’s death in 1934 and Hitler’s subsequent rise to power, the Führer made Guderian and Seeckt’s philosophies the foundation of a wide-ranging expansion and modernization of Germany’s armed forces. His brazen disregard of Versailles-imposed recruitment restrictions enabled the Heer to secretly train tens of thousands of conscripts a year. By 1938 it had grown to 36 infantry divisions totaling 600,000 men. Yet even as the Heer began its slow revival, senior Nazis were laying the foundations of an altogether different German military force.

In a political landscape of personal empire, few could match the appetite of Himmler when it came to craving power and influence. The head of the Nazi Party’s Schutzstaffel (SS)—which had originated as bodyguards for senior party members—Himmler wanted his own combat force capable of acting independently of the army. Thus in 1934 he created the SS-Verfügungstruppe (SS-VT), special-purpose troops at the disposal of the Nazi hierarchy for such tasks as suppressing civilian uprisings. In 1936 Himmler tapped respected former Heer Generalleutnant Paul Hausser to oversee SS-VT recruitment and training.

In a political landscape of personal empire, few could match the appetite of Himmler when it came to craving power and influence. The head of the Nazi Party’s Schutzstaffel (SS)—which had originated as bodyguards for senior party members—Himmler wanted his own combat force capable of acting independently of the army. Thus in 1934 he created the SS-Verfügungstruppe (SS-VT), special-purpose troops at the disposal of the Nazi hierarchy for such tasks as suppressing civilian uprisings. In 1936 Himmler tapped respected former Heer Generalleutnant Paul Hausser to oversee SS-VT recruitment and training.

Mindful of the need to keep the regular army in his corner, Hitler had the SS-VT placed under the direct oversight of the German High Command (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, or OKW). Cognizant of the threat the rival armed force could pose, the OKW kept a tight rein on the SS-VT’s supplies of recruits and equipment, to curb its growth and siphon off the best men for the Heer.

A European army in the classic mold, the regular army was dominated by a rigid class structure. Recruits were required to have at least a secondary education, while enlisted men and officers worked and lived separately. Strict adherence to formal military etiquette was expected. While the Heer drew primarily from German cities and towns for its manpower, the SS-VT recruited heavily from rural areas. The countryside at the time was a harsh breeding ground, turning out tough men used to living off the land—a characteristic that would prove especially useful during the June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union.

Though standards were predictably relaxed as the war took its toll, initial membership requirements for the Waffen-SS—as the SS-VT became known—were more exacting than those for the Heer. Potential recruits were required to prove their “Aryan” ancestry back several generations, be at least 5 feet 9 inches tall (an inch taller for the elite 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler, or LSSAH, a unit that originally served as the Führer’s bodyguard) and could be rejected for having even a single dental filling. Only one applicant in four was accepted into the elite force. In addition to classic military training (assault tactics, combat strategy, etc.) from former Heer instructors, the Waffen-SS training regimen placed a great emphasis on athletics, thanks to Hausser. Not just a side aspect of physical training, as in the Heer, individual and team sports were requisite. Waffen-SS recruits were encouraged to engage in boxing, gymnastics, indoor ballgames, swimming and other endeavors to help develop a competitive edge and a warrior-athlete ethos. Political involvement was also mandatory. Every member of the Waffen-SS was required to be a Nazi Party member. “For the Waffen-SS,” notes Jochen Böhler, co-editor of The Waffen-SS: A European History, “the National Socialist ideology was more fundamental; it was a raison d’être.”

Levels of political indoctrination were significantly higher than in the Heer, with recruits of all ranks given extensive classroom instruction in National Socialist ideology in preparation for their role as crusaders of the new Nazi order, members of a superior race that would take the battle to the Untermenschen (“inferior races”). Such indoctrination produced men of a fanatical zeal bred from self-assuredness and a firm belief they were the very definition of the Nietzschean Übermensch, or Aryan superman.

Each officer turned out by the Waffen-SS training academies at Bad Tölz and Braunschweig was required to serve at least a year in the ranks alongside ordinary troops, in order to foster greater camaraderie. Troops did not refer to superiors as Herr (sir), instead addressing one another by rank, and they eschewed traditional military salutes in favor of a loose version of the raised-arm Hitler salute. These were men whose belief in National Socialism and blind personal loyalty to Hitler far outweighed the importance of education and social standing. They had a reputation for leading from the front in combat, which resulted in noticeably higher officer casualty rates in the Waffen-SS, although Heer brass claimed that had more to do with the organization’s lack of professionalism.

As the Reich expanded across Europe following the 1939 outbreak of war, the Waffen-SS was able to draw on volunteers from ethnic German populations in conquered areas, over whom the OKW had no jurisdiction. As the war progressed, the organization cast its net still wider, recruiting volunteers from the populace of such Allied nations as Holland, Norway, France and Russia.

Despite the Waffen-SS’s early supply problems due to OKW fears about its growth, the weapons and equipment employed by both organizations were essentially the same, ranging from the ubiquitous MP 40 submachine gun to Panther and Tiger tanks.

From the outset, though, there were distinct differences in uniform. Members of the Waffen-SS wore their Hoheitszeichen—the national emblem depicting an eagle clutching a wreathed swastika—on the left sleeve rather than on the right breast, as in the Heer. The collar tabs for Waffen-SS privates through lieutenants colonel bore the SS runes (on the right) and rank insignia (left), rather than the traditional color-coded Prussian Litzen symbols worn by Heer enlisted men and officers to indicate rank and branch. Members of the SS-Totenkopfverbände—the organization that administered concentration camps—replaced the right-collar SS runes with the skull and crossbones “death’s head” patch. The Waffen-SS also used camouflage combat smocks; the Heer didn’t, with the exception of certain tank crews and snipers.

There was one other significant difference between the Heer and Waffen-SS: Each member of the latter was required to have his blood type tattooed on the underside of his left upper arm to make it easier for medics to treat him on the battlefield. Such tattoos had the unintended consequence of identifying captured troops as SS members, aiding in their postwar arrests and trials for war crimes.

It’s almost impossible to overstate Nazi Germany’s military achievements at the outset of World War II. Following its 1939 invasion of Poland, the Third Reich conquered Norway, France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands with astonishing speed. Those conquests were largely carried out by the Wehrmacht, Germany’s combined conventional forces, while the SS-VT—which remained under the operational control of the OKW—was largely reduced to a supporting role. Himmler and his subordinate commanders claimed the SS-VT was being starved of equipment and held back from combat solely to enable the Heer to gain all the glory. Confirming that impression, German army brass continued to deride the SS-VT’s poor performance and perceived lack of professionalism, suggesting “Himmler’s army” was good only for terrorizing civilians.

As the war ground on, however, the Reich increasingly relied on the zeal and dependability of the Waffen-SS. The force was reorganized and bolstered with additional personnel and better equipment, and its top divisions were soon equal to any unit the Heer could field. Sent east after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, the Waffen-SS earned a reputation for daring and a fanatical fighting spirit.During the 1943 Third Battle of Kharkov for example, SS-Standartenführer Joachim Peiper, a former adjutant to Himmler, led the 3rd Battalion of the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Regiment through 30 miles of Russian lines to rescue the Heer’s encircled 320th Infantry Division and then escorted the unit’s packed ambulances back to the safety of German lines. During the same battle Hausser, then commanding II SS Panzerkorps, withdrew his forces to prevent encirclement, regrouped and, in direct disobedience of Hitler’s orders, launched a counteroffensive that recaptured Kharkov and halted the Soviet offensive, sparing Generalfeldmarschall Erich von Manstein’s Army Group South from annihilation.

Perhaps the most fiercely debated aspect of the relationship between the Heer and Waffen-SS is the question of which organization was more complicit in war crimes. The debate first surfaced in the immediate postwar period as Allied prosecutors prepared for and conducted the 1945–46 Nuremberg trials. Some observers and participants alike felt the Waffen-SS was scapegoated as the sole perpetrator of war crimes, while the Heer got off lightly. Relatively few senior army officers were tried at Nuremberg, while the Waffen-SS was deemed a criminal organization. That was an understandable conclusion, given the latter’s well-documented record of savagery against both civilians and Allied military personnel. The brutality routinely displayed by Waffen-SS units was a direct result of their extensive political indoctrination. In their minds they were to be the merciless spearhead of a war against inferior races.

That belief played out on both the Eastern and Western fronts. Among the most egregious examples in the West occurred in the central French village of Oradour-sur-Glane in the aftermath of the 1944 Allied landings in Normandy. Acting on faulty intelligence about a captive German officer, on June 10 members of the 4th SS-Panzergrenadier Regiment “Der Führer,” part of the 2nd SS Panzer Division “Das Reich,” murdered 642 townspeople—men, women and children—then razed the village. Few survivors remained to tell the tale. Six months later, on December 17, Waffen-SS troops under the command of Peiper—the hero of Kharkov—murdered 84 American POWs outside the Belgian village of Malmedy.

Despite such documented atrocities, however, the Waffen-SS “by no means had a monopoly on brutality, atrocity and war crimes,” writes Harry Bennett of the Second World War Military Operations Research Group, a history professor at Britain’s University of Plymouth.

Despite protestations to the contrary by many of its senior officers, the Heer also committed war crimes, killing thousands of civilians during the invasion of Poland and committing widespread atrocities during antipartisan operations in Yugoslavia and Russia.

“For example,” Bennett notes, “the forces of Field Marshal [Walther] von Reichenau in Russia in late 1941 took part in murderous actions against Jews, following his issuing of an order in October to treat Jews as de facto partisans—to shoot them out of hand or to hand them over to the units of the Einsatzgruppen (SS death squads) for elimination. Reichenau was both a member of the Nazi Party and an anti-Semite, blurring the lines between the officer corps and the Nazi elite.”

While many senior Heer officers were tried for war crimes, and some—including Generalfeldmarschall Wilhelm Keitel and Generaloberst Alfred Jodl—faced execution, the Wehrmacht was not designated a criminal organization, as was the Waffen-SS. That fact helped perpetuate a postwar myth in West Germany that all war crimes committed by German personnel were the work of the Waffen-SS and other SS organizations, and that the regular military forces, including the Heer, were blameless of any wrongdoing.

That belief was further reinforced in the decade following the war, as the United States, Britain and France sought to turn West Germany into a valued ally against the new Soviet threat. Integral to that process was the creation of the Bundeswehr, the postwar West German armed forces, with the Deutsches Heer as its ground-combat component. The majority of those drawn into the new West German armed forces were inevitably World War II veterans, though anyone seeking to join the Bundeswehr faced vetting by a screening board that examined his wartime conduct in detail. While former Waffen-SS members who passed the screening process were allowed to serve, they were far outnumbered in the new armed forces by former Wehrmacht members. In one sense it marked the final ascendency of one of Hitler’s armies over the other. MH

Mark Smith is a journalist and freelance writer based in Liverpool, England. For further reading he recommends The Waffen-SS: A European History, edited by Jochen Böhler and Robert Gerwarth, and The Wehrmacht: History, Myth and Reality, by Wolfram Wette.

This article appeared in the July 2020 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: