Rambling Rose

Allied troops in the South Pacific during World War II were bombarded with propaganda dished out over the airwaves by English-speaking women in Japan, the Philippines, and elsewhere. Although these broadcasters had different on-air names and personas, their coordinated campaign to demoralize soldiers—and the soldiers’ families back home—earned the women almost mythical powers in the American news media and the nation’s collective psyche. The troops, who craved the music served up by the propagandists but dismissed the taunts directed at them, came to refer to this sorority of shills for the Japanese Empire with one iconic name: Tokyo Rose.

But if Tokyo Rose was the wartime equivalent of a multiple personality disorder, there was one woman who emerged as the public face of this scorned clique: Iva Toguri, who had been born in Los Angeles to Japanese parents. Following her graduation from UCLA in 1941, Toguri traveled to Japan to visit a sick aunt, only to get stranded there following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Months later Radio Tokyo hired Toguri to type scripts for the propaganda programs directed at American GIs, and it soon asked her to host such a show. And so the gravelly voiced “Orphan Ann” took the microphone for The Zero Hour, although with ulterior motives: The show’s producer, an Australian prisoner of war, schemed to sabotage it with sarcasm too subtle for the Japanese to detect, and Toguri played her part with understated flair. (“Here’s the first blow at your morale,” she once told her audience, “the Boston Pops playing ‘Strike up the Band!’ ”)

Recommended for you

When the war ended, an American magazine reporter in Japan identified the married Iva Toguri D’Aquino as the infamous Tokyo Rose. U.S. army authorities arrested her on suspicion of treason but let her go when the FBI and the Counterintelligence Corps decided that there wasn’t enough evidence to warrant prosecution. On returning to the States, she was swept up in a media frenzy of anti-Japanese sentiment and retried. In 1949 she was convicted on one count of treason and sentenced to prison. Nearly three decades later, however, two key prosecution witnesses recanted their testimony, and President Gerald Ford granted her a full pardon.

When Harried Met Sally

In the summer of 1943, as Allied forces began their northward push into the Italian mainland, Benito Mussolini’s government hired Rita Luisa Zucca, a New York–bred Italian-American, to cohost Jerry’s Front Calling—a nightly dose of radio propaganda that, relying on German intelligence, aimed to confuse enemy troops. The 30-year-old Zucca, who had a particularly seductive voice, started each broadcast with “Hello, suckers!” and ended it with “a sweet kiss from Sally,” a nod to the Axis Sally handle by which she had become known.

But as Americans fighting in other parts of the European theater knew, another Axis Sally—this one stationed in Berlin—had been plying the same deceptive tradecraft for well over a year.

Mildred Elizabeth Sisk, who became Mildred Gillars after taking the name of her mother’s second husband, was born in Maine and graduated high school in Ohio.

After her acting career fizzled, Gillars left New York for Germany, where before World War II she worked as a host of radio shows about music and art. As hostilities ramped up, “Midge,” as she was known on air, was recruited as the talent for Home Sweet Home—a toxic daily stew of Nazi propaganda, anti-American derision, and virulent anti-Semitism. But “Midge at the mic” also served up such a great playlist and had such a compelling voice that soldiers couldn’t get enough of her.

Following the war, U.S. authorities tracked down Gillars and returned her to the States, where she was convicted on one count of treason. She spent 12 years behind bars, after which she taught at a Catholic school in Ohio and then returned to college. Rita Zucca, the come-lately who was often confused with the original Axis Sally (much to Gillars’s consternation), escaped a similar fate because she had given up her U.S. citizenship. But an Italian court found her guilty of collaboration, and she served nine months of a 53-month sentence.

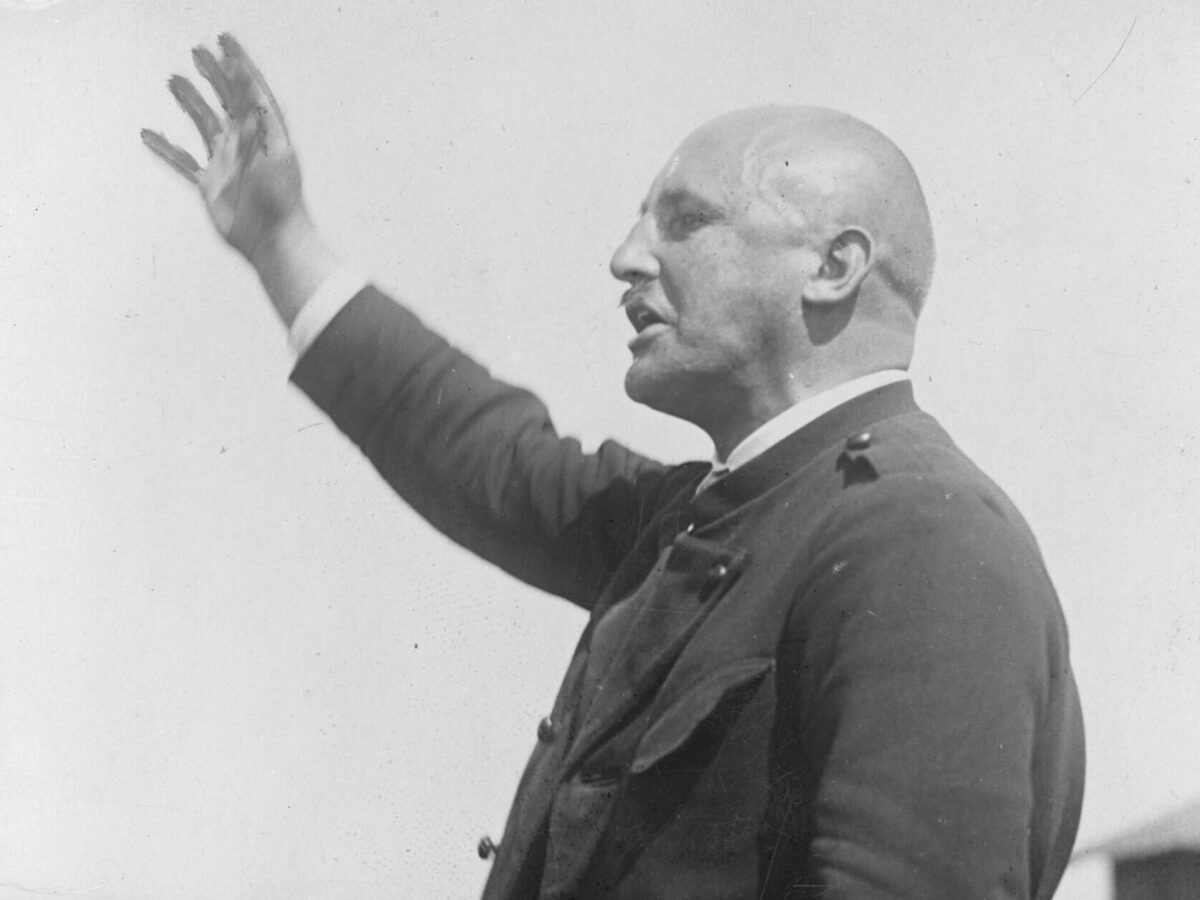

The War Lord

As World War II raged, Germany’s minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, used an elaborate strategy of radio broadcasting to not only shore up the Third Reich internally but also deliver a steady stream of disinformation and demoralizing pronouncements to enemy states, most notably the United Kingdom. While those efforts flopped in some countries, a breakout star known as Lord Haw Haw was so popular with British listeners that antsy government officials were forced to concoct strategies aimed at tamping down his influence.

Like the Tokyo Roses in the Pacific Theater, a number of men were vested with the Lord Haw Haw nom de guerre. But the most famous, accomplished, and notorious of the group was William Joyce—“the best horse in my stable,” Goebbels noted.

Born in Brooklyn to an Irish father and an English mother, Joyce’s family moved to Ireland when he was three. They later moved to England, where he became a rabid anti-Semite, an admirer of Adolf Hitler, and a prominent member of the British Union of Fascists. In the summer of 1939, with the war looming, the Joyce family moved to Germany.

Joyce was soon hired by the Nazis’ English-language radio service, where he used his engaging banter and curious, nasal, high-pitched voice to lure a nightly audience of some seven million. Germany Calling, which was broadcast from Berlin and then Hamburg, made Joyce a household name. He could alternately amuse or strike fear in his listeners. One night, for example, he announced an impending Luftwaffe bombing of a factory north of London, shutting down operations after worried workers didn’t show up for their shift.

Joyce and his wife tried to flee at war’s end, but they were taken into custody at Flensburg, near the German border with Denmark, after a British soldier recognized his voice. Because Joyce had applied for a British passport before leaving for Germany, he was tried for treason. (His wife was not charged.) A London jury found him guilty, and at age 39, he was hanged.

Heil and Farewell

On October 1, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt directed Attorney General Francis Biddle to consider bringing charges of treason against a cadre of American expatriates whose radio broadcasts were aiding Hitler and other Axis leaders. The following January, the head of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division produced for Biddle a legal memorandum arguing that indictments should be sought for seven current or former U.S. citizens, despite their being beyond the reach of U.S. authorities until hostilities ended.

That notorious roster of five men and two women, whose “extremely seditious” gush of enemy boosterism originated from Rome and near Berlin, included veteran

journalists and, most prominently, the poet and literary editor Ezra Pound, who produced numerous commentaries for the Italian government that lambasted both Roosevelt and his forsaken homeland. But perhaps the highest-profile propagandist on Biddle’s “enemies list” was Frederick W. Kaltenbach, a German-American born in Dubuque, Iowa. Kaltenbach’s Monday-night Letters to Iowa radio show, delivered with a down-home and folksy Midwestern lilt and peppered with wise-cracking takedowns of Roosevelt and British prime minister Winston Churchill, made him a prominent part of the Nazis’ efforts to convince Americans that supporting Britain’s military campaign against Germany would put the United States on a road to ruin.

In fact, Joseph Goebbels’s propaganda operation so valued Kaltenbach’s efforts to influence public opinion in North America that the former high school teacher was soon featured throughout the week on Fritz and Fred, Military Review, and other popular German radio shows. And his fame only grew when the Germans also began broadcasting his routine in Britain, where his oratorical resemblance to William Joyce (Lord Haw Haw) earned him the nickname Lord Hee Haw.

But Kaltenbach’s star faded in the summer of 1943, when he and other shortwave rabble-rousers were indicted in absentia for treason. By all credible accounts, he died a few years later after Soviet agents in Berlin took him into custody.

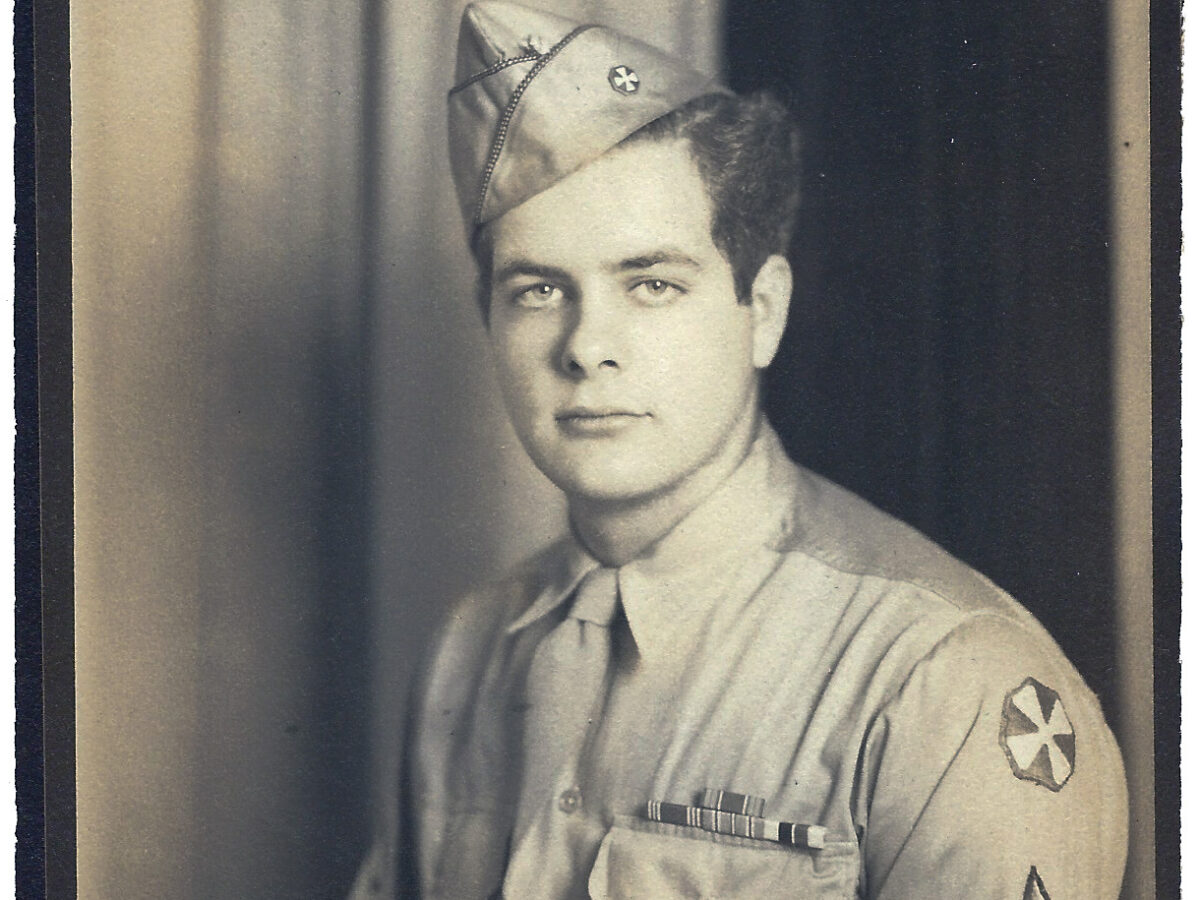

Surh Loser

A characteristic typically shared by wartime propagandists is that while their cock-and-bull stories may be as transparent as glass, their shtick is good enough to keep listeners returning for more. But in the summer of 1950, when North Korean troops occupying the South Korean capital debuted their “Radio Seoul” programming for arriving American soldiers, the on-air talent—Anna Wallace Suhr—proved to be so boring that acquaintances insisted she was being forced under duress to read her scripts.

Born in Arkansas, Anna Wallace studied to be a Methodist missionary and was dispatched to Seoul and then Shanghai, where she married a left-leaning Korean school teacher. The couple subsequently returned to Seoul, where they later pledged their loyalty to the North Korean regime after its invading troops occupied the city.

Suhr, who had been stripped of her American citizenship as a result of her marriage, was tapped to deliver daily installments of North Korean agitprop, which early on included this suggestion to GIs: “Return to your corner ice cream stores in the States.” A New York Times correspondent writing from Tokyo assessed her skills perfectly: “In flat Midwestern accents her voice drones doggedly through page after page of a detailed accounting of the number of bombs dropped, civilians killed and injured, with occasional references to ‘American imperialists’ and ‘Wall Street invaders’….She sounds bored.”

American soldiers subjected to her monotones gave her such nicknames as Rice Ball and Rice Bowl Maggie before settling on Seoul City Sue—a moniker, it’s believed, that paid homage to country musician Zeke Manners’s popular 1946 song, “Sioux City Sue.” Her lackluster run ended in August 1950, when a U.S. air strike took out Radio Seoul’s transmitters.

But if Seoul City Sue lacked the chops of, say, Tokyo Rose, she nevertheless earned her stripes two decades later, when someone who’d assumed her identity was heard spewing propaganda over the PA system on multiple episodes of the TV show M*A*S*H.

A Girl Named Thu

In March 1965, shortly after American combat troops were deployed to South Vietnam, the North Vietnamese Defense Ministry countered with a sweet-talking radio host who would amuse, bedevil, entertain, inform, annoy, and captivate GIs until 1973, when the withdrawal of U.S. combat troops finally wound down.

The young woman behind the Voice of Vietnam microphone was Trinh Thi Ngo, although she used the alias Thu Huong (translation: Autumn Fragrance) because it was easier for non-Vietnamese listeners to pronounce. But from Quang Tri to the DMZ, Americans battling the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong guerrillas knew her as Hanoi Hannah.

As a child, Trinh Thi Ngo was so taken with American films—Gone with the Wind was a favorite—that her parents paid for private English tutors, and her study of the language continued in college. In fact, she became so fluent, with no hint of a foreign accent, that the Hanoi government’s propaganda department tapped her to host a twice-weekly five-minute broadcast designed to demoralize American troops. Eventually, her show was expanded to 30 minutes and repeated several times daily.

The broadcasts inevitably had the same beginning (“This is Thu Huong calling American soldiers in South Vietnam”), after which she’d play a sad or nostalgic song designed to make her listeners homesick. She then read scripts prepared by North Vietnamese Army propagandists, who lifted—and often embellished—stories from American publications about antiwar demonstrations, civil unrest, and military setbacks. On Friday afternoons, she read the names and hometowns of fallen American GIs from Stars and Stripes. At other times she urged soldiers to frag their offices or desert their units, since they were, she said, fighting an unjust and immoral war.

“I tried to be friendly and convincing,” she told the Los Angeles Times in 1998. “I didn’t want to be shrill or aggressive. For instance, I referred to the Americans as the adversary. I never called them the enemy.”

The Bob Hopeless Show

In March 2003, when the U.S.-led “Coalition of the Willing” invaded Iraq to dismantle the weapons of mass destruction purportedly stockpiled by the government of President Saddam Hussein, the Pentagon authorized more than 700 journalists to be embedded with troops for major combat operations. A year later, in a panel discussion that examined media coverage of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Marine Corps public affairs officer Lieutenant Colonel Rick Long minced no words about why reporters had been given those ringside seats: “Frankly, our job is to win the war,” he explained. “Part of that is information warfare. So we are going to attempt to dominate the information environment.”

But while that strategy yielded largely favorable coverage, the Iraqis produced a media counterweight with whom no network anchor could hope to compete. His name was Muhammad Saeed al-Sahhaf, but captivated TV viewers—in a nod to Hanoi Hannah and his other alliterative wartime forebears—crowned him Baghdad Bob. And in short order, his laughably outrageous and patently bogus claims about the enemy (“They’re coming to surrender or be burned in their tanks”; “The infidels are committing suicide by the hundreds on the gates of Baghdad”) also earned him the titles Minister of Misinformation and Comical Ali—a knockoff of the “Chemical Ali” nickname bestowed on former Iraqi defense minister Ali Hassan al-Majid.

President George W. Bush admitted he was an al-Sahhaf fan, and he was in good company: When some bemused New Yorkers created a website cataloging the lies of the beret–wearing former diplomat, the crush of traffic overwhelmed the server. Sales of T-shirts with his likeness were particularly brisk.

Baghdad Bob gave his final press briefing on April 8, 2003, the day before Coalition forces formally occupied the Iraqi capital. Despite his renown, the U.S. military nevertheless omitted him from its postwar deck of playing cards that identified the most-wanted members of Saddam Hussein’s regime.

Alan Green is a journalist who lives in the Washington, D.C., area.

this article first appeared in military history quarterly

Facebook: @MHQmag | Twitter: @MHQMagazine