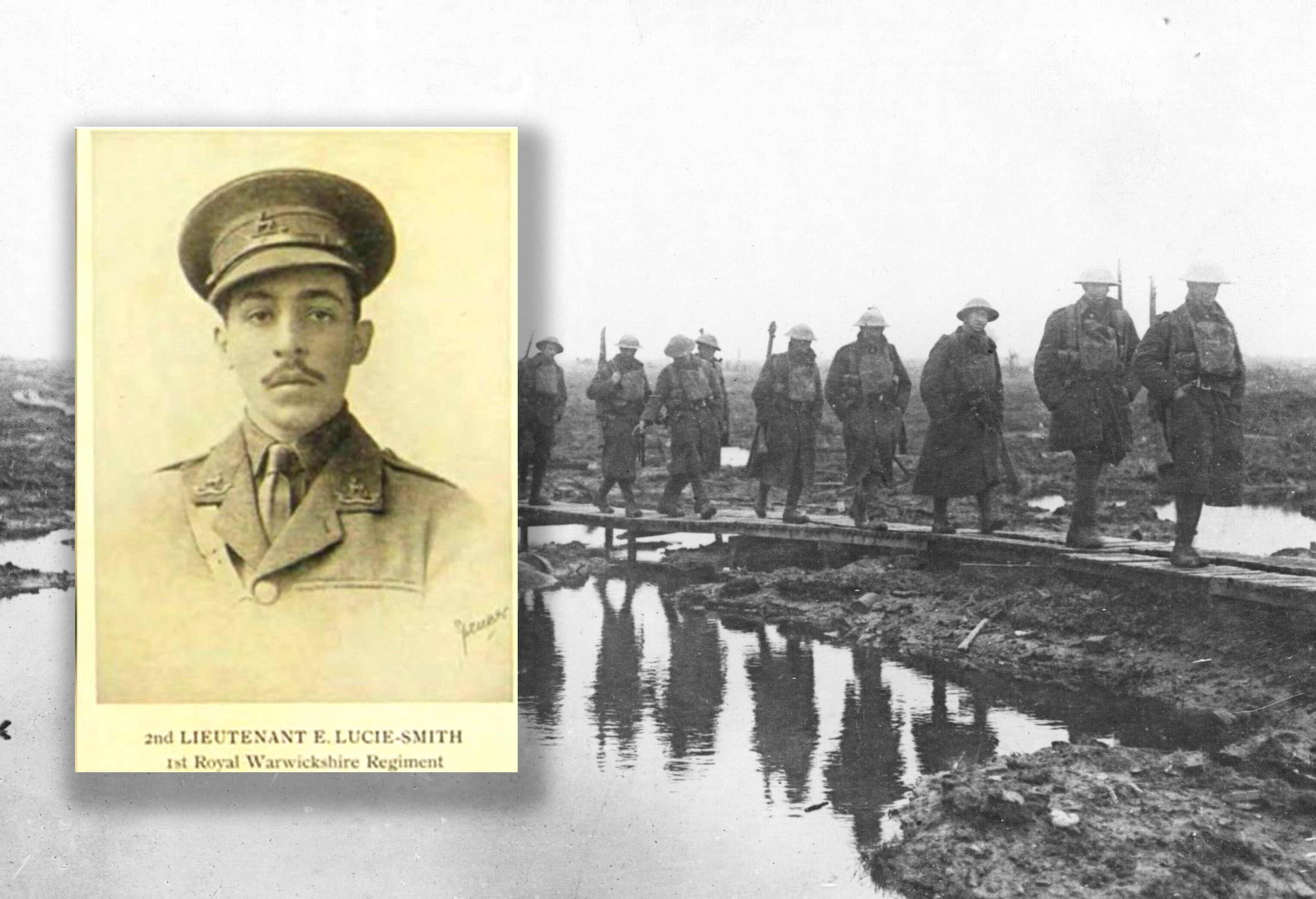

The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers Museum (Royal Warwickshire Regiment) in Warwick, England has acquired a World War I-era memorial plaque commemorating the first commissioned officer from an ethnic minority background in the British Army.

Lt. Euan Lucie-Smith, born in Jamaica on Dec. 14, 1889, was of multiracial heritage. His parents were John Barkley Lucie-Smith, a descendant of white civil servants, and Catherine “Katie” Lucie-Smith, whose father Samuel Constantine Burke was a distinguished Jamaican politician of black heritage who advocated for social justice and civil rights.

Commissioned into the British Army on Sept. 17, 1914, Lucie-Smith was killed in action on April 25, 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres—nearly three years before Walter Tull, who previously was thought to be the British Army’s first commissioned multiracial officer.

This discovery makes Lucie-Smith’s bronze memorial plaque an artifact of great historic significance.

“It represents a first. The first officer from an ethnic background to be commissioned into the British Army, to be commissioned into a British regiment, and sadly to die on the battlefield,” Lt. Col. (Ret’d) John Rice, Chair of Trustees of the museum, told the BBC.

Now Lucie-Smith will be among those honored in the museum’s collection. The museum tells the history of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, which later became the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. The regiment counts many British military heroes among its sons, most notably Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery and Field Marshal William Slim, and including soldiers killed by the S.S. while defending Wormhoudt, France in 1940 and others who fought at Sword Beach on D-Day in 1944.

“He [Lucie-Smith] shows the contribution of the Commonwealth countries in the Great War,” curator Stephanie Bennett told Military History in an interview.

“He is a link between the past and the present as soldiers from the Commonwealth countries continue to play an important part in the British Army today,” said Bennett. “It is an important story because it also shows the diversity of the British Army.”

Lucie-Smith’s story, largely forgotten, came to light with the auction of a memorial plaque by Dix Noonan Webb. Auctioneers had estimated the so-called “dead man’s penny” memorial—a bronze plaque given by the King to the nearest next of kin of men and women who died during World War I—would be sold for between £600 to £800.

However, the museum won a fierce competition to obtain the plaque at auction and, thanks to community effort, managed to get the plaque at a hammer price of £8,500. With added commission and VAT, the total amounted to £10,540—which was 13 times the original estimate.

“Indeed, this was an exceptional sum for a World War I memorial plaque; it was certainly a lot of money,” said Bennett, expressing gratitude to museum trustees, grant providers and individual donors for their assistance. “It was very much a team effort and acquiring the plaque would not have been possible without everybody.”

Lucie-Smith, who served in the 1st Battalion of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, came from what would be called a “traditional officer class,” according to Bennett. He attended two public schools in England.

In a strange coincidence, Lucie-Smith was a boarding student in 1904 at St. John’s House in Warwick, where the museum is currently located.

The youngest of three children, he was commissioned into the Jamaica Artillery Militia on Nov. 10, 1911. He was killed at St. Julien on April 25, 1915 during the Second Battle of Ypres. An eyewitness reported that he sustained a shot wound to the head.

“Casualties were heavy that day,” according to Bennett. “He was one of 12 officers who were killed at that action and six were wounded. Five hundred other ranks were also killed, wounded or missing.”

Lucie-Smith was unmarried and left behind no direct descendants, although he has living relatives. He has no known grave. His memory is preserved on the second and third panels of the Ploegsteert Memorial in Belgium.

“Euan sadly died three days after his father, so his mother was grieving for both loved ones at the same time,” said Bennett.

His memorial plaque, inscribed with the words, “He died for freedom and honour,” is planned to be displayed at the museum at St John’s House in Warwick in spring next year.

“We hope to display the plaque in the Easter school holidays when visitors, especially people from Warwickshire will be able to see it for the first time,” Bennett said. “We can carry out more research, display it in a case on its own and publicize the occasion. I am sure that we will plan a ceremony for the re-opening of the museum at a later date at Pageant House in Warwick which will hopefully either be at the end of 2021 or early in 2022.”

Afterwards the historic plaque will be on loan next year to the National Army Museum in London as part of a temporary display from after Easter to the end of September 2021.