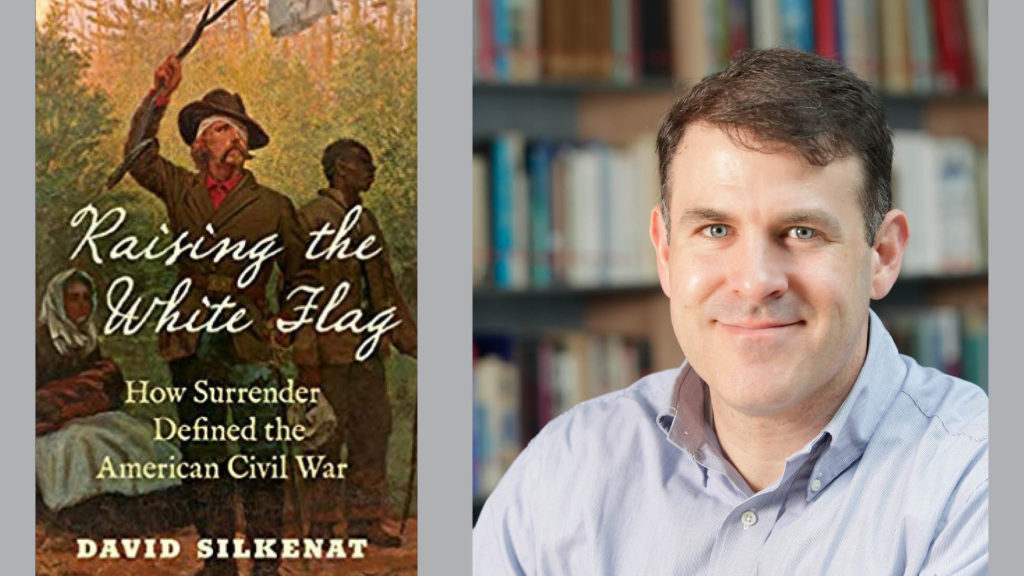

In Raising the White Flag: How Surrender Defined the American Civil War (University of North Carolina Press, 2019, $39.95), David Silkenat, senior lecturer in American history at the University of Edinburgh, examines how 19th century attitudes toward civilized war and honor made it possible for Civil War soldiers to surrender without shame. In the 150 years since the Civil War’s conclusion, however, Silkenat argues that American attitudes toward surrender have changed dramatically, leading the U.S. military to train service members to see raising the white flag as an act of dishonor.

One in four Civil War soldiers surrendered at some point during the conflict. Why was surrender so common?

Officers saw surrender as a legitimate, proper, and honorable way to end a battle that they were going to lose. In April 1861, Major Robert Anderson surrendered his garrison at Fort Sumter after the fort was bombarded for 34 hours. The Union greeted Anderson as a hero, and the reaction established that a commander could surrender honorably if continuing to fight would lead only to the needless loss of life. On the battlefield, individual soldiers threw down their weapons and asked to be taken prisoner when they saw no alternative. Most soldiers thought allowing themselves to be taken prisoner was better than trying to fight it out in a desperate situation.

What were professional officers taught about surrender?

One thing taught at West Point was wars between civilized nations should be fought according to largely unwritten but widely accepted rules. One of the principles was that when an enemy offers to surrender, the victor is supposed to accept.

What does it say about soldiers’ attitudes about honor and duty that surrender was so accepted?

Soldiers who surrendered on the battlefield weren’t usually cowards or shirkers. In fact, they tend to be the bravest soldiers—the last to retreat when the line has broken. It was seen as dishonorable to kill a man who had raised his hands. Soldiers were often paroled after they surrendered as long as they pledged on their honor not to fight again until they were told that they had been formally exchanged for prisoners on the other side. One of the remarkable things about Civil War soldiers is that they took being paroled extremely seriously. For example, some of the Confederate soldiers paroled after the fall of Vicksburg thought they had been formally exchanged but actually had not been, and when forced to surrender a second time at Chickamauga they were horrified that they were seen as having acted dishonorably.

Talk about the Dix-Hill Cartel.

At the beginning of the war, neither side was interested in holding large numbers of enemy soldiers because of the expense. Confederates, however, believed that participating in prisoner exchanges would lend legitimacy to the argument that the Confederacy was an independent, civilized nation. President Lincoln did not want encourage foreign recognition of the Confederacy, but public pressure led him in July 1862 to agree to a formalized exchange arrangement named after its chief negotiators, Union Maj. Gen. John A Dix and Confederate Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill. Under the Dix-Hill cartel, paroled prisoners were honor-bound not to resume fighting until they had been exchanged for an equivalent number of prisoners from the other side. During the year or so that the cartel was active and healthy, soldiers and officers knew that if they surrendered they would be treated fairly well and held prisoner only fairly briefly. The cartel broke down in the second half of 1863 after both sides accused the other of cheating and because of the Confederacy’s announcement it would not treat captured African-Americans soldiers as prisoners of war but instead as fugitive slaves. There was a sharp dropoff in exchanges and horrible prisoner of war camps such as Andersonville were opened.

What was the significance of the Lieber Code?

According the Federal government’s Lieber Code, legitimate soldiers who surrendered were entitled to adequate food, shelter, and humane treatment. For the code’s author, legal philosopher Francis Lieber, a legitimate soldier fought in uniform and was part of a recognized chain of command. Lieber stated that guerrillas who didn’t play by the rules of warfare—they didn’t wear uniforms, hid in the civilian population, stole and killed indiscriminately—were criminals and did not deserve the protections a legitimate soldier did. The Lieber Code signaled that guerrillas, most of whom fought for the Confederacy, could not surrender for fear of being executed.

What about African American soldiers?

While official Confederate policy deemed captured African Americans fugitive slaves who should be returned to their masters, in practice, captured black soldiers often faced execution. The most famous example of this was Fort Pillow, but there were dozens of incidents in which African American soldiers were put to death after surrendering. According to Lieber, African Americans fighting in uniform were legitimate soldiers who deserved the same rights as white soldiers. Black soldiers feared capture and fought ferociously.

How did President Lincoln’s “malice toward none” policies affect Confederate commanders’ willingness to surrender?

Lincoln told Grant to offer the Confederates almost anything they could want, but not to make any promises about political questions. The terms Grant offered Lee at Appomattox Courthouse Grant followed Lincoln’s guidelines. Surrendered soldiers were not to marched off to prison camps; they would be left alone as long as they upheld the terms of their parole. Grant tried very hard not to shame Lee or any of the Confederate soldiers. He sent orders forbidding celebrations of the surrender. Lee knew he was being given very generous terms and he told his men they could accept parole without dishonor.

Most of Lee’s army laid down its arms. But as other Confederate commanders surrendered, more and more soldiers stole away with the intention of joining units that were still fighting. Why?

In each of the Confederate surrenders, the vast majority of the men were happy that the fighting was over. But there was a die-hard core in each of these Confederate armies that refused to accept defeat. A small part of Lee’s army tried to join Joseph Johnston in North Carolina, a fraction of Johnston’s army tried to slip away and join Richard Taylor’s army in Alabama, and some of Taylor’s army tried to join Edmund Kirby Smith’s Trans-Mississippi army. When Kirby Smith’s army eventually surrendered, a die-hard remnant marched into Mexico rather than accept defeat. What’s interesting about these die-hards who refused to surrender is that many of them would in years to come join white supremacist paramilitary organizations like the Ku Klux Klan and continue to fight the Civil War on different terms and using different methods.

Twenty-first century American attitudes have toward surrender have changed. Can you explain that?

The Civil War generation had a very different understanding of what surrender meant than Americans do today. The Civil War generation believed rules governing surrender distinguished a conflict as a civilized war. In the generations that followed, however, American attitudes toward surrender shifted meaningfully. In the 20th century, it became standard national ideology that Americans never surrendered. If taken prisoner, they refused to cooperate. One thing that has changed is the recognition that American or Allied prisoners of war captured by the North Vietnamese, al Qaeda or the Taliban could not expect humane treatment. Surrendering when you think torture or death is the likely outcome is a very different decision than what was faced by most soldiers in the Civil War.