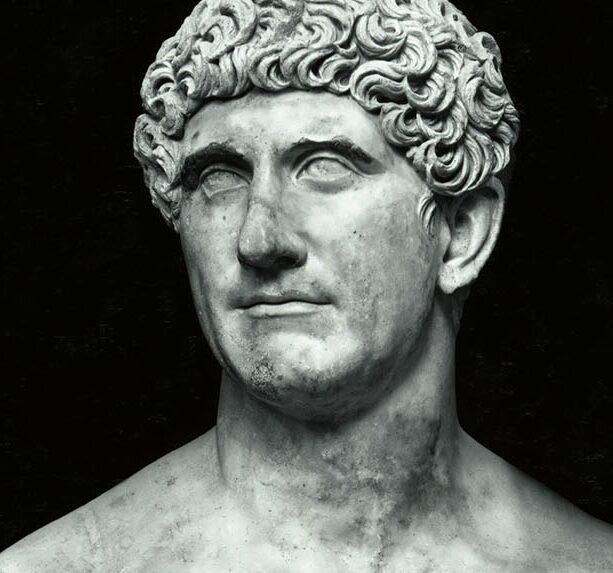

Marcus Antonius (83–30 bc) would have been no one’s pick to become a great leader of men in battle. A hedonist given to drunkenness, debauchery, partying and pranks, always in debt, and oft married and divorced, Mark Antony (as he is familiarly known) was anything but a sterling character by either ancient Roman or modern standards.

Like Alexander and Hannibal before him, Antony was a spotty strategist who often failed to appreciate the larger political context in which he was operating. Incapable of long-term planning and lacking the discipline to carry it out, he was a man who lived for the moment, at his best when circumstances were at their worst. Like Napoléon Bonaparte, Antony was capable of dashing bravery and tactical brilliance. Also like Napoléon, when he blundered, he did so on a colossal scale. Yet despite his many flaws Antony came within an ace of being the most important figure of his day.

Antony began his military career at age 27 when invited by Syrian proconsul Aulus Gabinius, a family friend, to participate in a 56 bc expedition to suppress a Jewish revolt in Judea. Given command of the cavalry, Antony was the first to storm the wall at Alexandrium, a fortified town overlooking the Jordan River northeast of Jerusalem. Honored for his exploit, Antony led follow-up sieges against the Dead Sea forts of Hyrcania and Machaerus, forcing them to surrender. During the campaign the young commander endeared himself to his troops by eating, drinking and carousing with them, a habit he maintained throughout his military life.

The next year Ptolemy XII, deposed king of Egypt, hired Gabinius and his army to restore him to the throne. Again permitted to take the lead, Antony’s cavalry cleared the route for the main army and soon arrived outside the fortress city of Pelusium. Catching the enemy by surprise, Antony captured the city by encouraging its garrison to revolt. Ptolemy wanted to put all prisoners to the sword, but Antony pleaded successfully for their pardon, earning him the Egyptians’ affection. The army then marched on Alexandria, where Antony led another daring cavalry raid, encircling the enemy and forcing its surrender. It was there the dashing Roman commander first met Ptolemy’s daughter Cleopatra, then 14-year-old heir to the Egyptian throne.

Antony resumed his self-indulgent life of drinking, gambling and womanizing in Rome before joining his mother’s distant cousin, Gaius Julius Caesar, as a legate in Gaul in early 54 bc. A staff officer, Antony likely accompanied Caesar on his invasion of Britain. The fighting there was arduous, and Antony must have performed well, as by following spring Caesar had marked him as a promising unit commander and political agent. In 52 bc he sent his young relative to Rome to stand for election as quaestor, the bottom rung of public office. After winning election, Antony rejoined Caesar in Gaul, rising through the ranks to command of a legion and participating in the brutal suppression of the Gauls.

Returning to Rome in 50 bc, Antony won election as a tribune. Within months senators opposed to Caesar’s rising power ejected Antony when he tried to speak in his commander’s defense. With civil war imminent, Antony returned to his legion. In January 49 bc Caesar and his army crossed the Rubicon River and marched toward Rome. At the head of the cavalry and some 2,000 infantrymen, Antony marched west across the Apennine Mountains then south on the Cassian Way, capturing Arretium (present-day Arezzo) and opening the road south to the capital. Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) and the Senate fled east, crossing the Adriatic to the Roman province of Epirus in Greece, and Caesar and Antony spent the next two months securing all of Italy. In April Caesar left Rome to fight Pompey’s legions in Spain, appointing Marcus Lepidus as acting consul of Rome and Antony as governor of Italy and commander of its forces.

In early January 48 bc Caesar led an army of seven legions and cavalry (about 25,000 men) from Italy to Epirus to deal with Pompey, leaving behind the rest of the troops (some 20,000 men and 800 horses) under Antony’s command. Bibulus, admiral of Pompey’s fleet, bottled up Antony’s ships at Brindisi for three months, preventing his reinforcement of Caesar. On learning Bibulus had fallen deathly ill, Antony braved the blockade, landed north of the opposing Roman armies and linked up with Caesar.

Caesar besieged Pompey’s larger army at Dyrrhachium (present-day Durrës, Albania) from April through July, during which time Antony distinguished himself in action. On July 10 Pompey used his superior numbers to outflank the besiegers on both ends of the line. When Caesar’s army broke under the attack, Antony rushed into the fray, rallied the troops and counterattacked, robbing Pompey of his momentum. Antony then held while Caesar withdrew the main body of his army inland. The tribune’s boldness burnished his reputation as a field commander and, more important, solidified Caesar’s trust in him.

Marching southeast to Thessaly, Caesar regrouped his remaining 12 legions (30,000 men) and 1,000 cavalry. Pompey soon arrived with his 60,000 men and 7,000 horses. The armies camped on opposite sides of the Pharsalian plain and met in battle on August 9. Stationing himself on the right opposite Pompey, Caesar held six cohorts of infantry in reserve, hidden from sight behind his cavalry. When Pompey attacked, Caesar’s horsemen resisted only briefly before withdrawing. Pompey’s cavalry fell for the ruse and rushed in, exposing its flank to Caesar’s hidden troops. Armed with thrusting spears, his infantrymen drove through the onrushing horsemen straight into Pompey’s camp, forcing him to flee. Antony, commanding the VIII and IX legions, had held the left flank despite being heavily outnumbered and defending poor ground. Caesar lost 250 dead and 2,000 wounded to Pompey’s 15,000 dead and 24,000 captured. At that the Roman protectorates and provinces in Greece and Asia declared for Caesar.

Antony’s stalwart defense in the decisive victory at Pharsalus earned him a glorious return to Rome to assume dictatorial powers as sole magistrate, while Caesar pursued Pompey to Egypt, confirmed the latter’s assassination, then helped Cleopatra depose her father, Ptolemy. Antony, meanwhile, fell back into his former debauched lifestyle, his tenure marked by corruption and misrule. Regardless, when Caesar returned to Rome in October 47 bc to assume the consulship, he retained Antony as his deputy, making him the second most powerful man in Rome.

Following Caesar’s assassination on March 15, 44 bc, Antony for once proved disciplined. Seeking to avoid civil war, he granted amnesty to the assassins and their Senate supporters, permitting them to leave the capital. Among the lead conspirators, Marcus Junius Brutus fled north to Cisalpine Gaul, Cassius east to Syria. Antony was left the most powerful person in Rome, though the presiding Republicans judged he lacked the genius, self-control, ambition and ruthlessness to be another Caesar.

Fresh from military training, Octavian—Caesar’s great nephew, adopted son and heir—arrived in the capital in May. When Antony refused to recognize the 18-year-old as Caesar’s political heir or turn over his inheritance—which Antony had spent to keep his own troops loyal—Octavian rallied Caesar’s veterans from Campania and began to amass an army. Seeking to avoid political machinations in Rome and to retain an army of his own, Antony marched to Cisalpine Gaul that December and besieged Brutus in Mutina (present-day Modena). In early January 43 bc the Senate, led by Antony’s enemy Marcus Tullius Cicero, declared him an outlaw, appointed two new co-consuls, Aulus Hirtius and Vibius Pansa, ratified Octavian’s army and sent their collective legions north to relieve Brutus. A forewarned Antony left his brother in charge of the siege and marched to meet them.

On April 14 Antony led a masterly ambush of Pansa’s troops amid a forest and marsh near the northern Italian village of Forum Gallorum. Pansa was mortally wounded, his troops routed, but Antony’s men cut short their spontaneous celebration when surprised by Hirtius and his fresh troops. Antony’s cavalry fought bravely, but by nightfall half of his men were dead, the survivors on the run.

Six days later Octavian’s legions combined forces with those of Hirtius, forming a 45,000-man army that defeated Antony’s exhausted, vastly outnumbered men at Mutina, though Hirtius was slain in the fight, leaving Octavian in sole command. In an arduous march Antony led his survivors over the Alps into Transalpine Gaul, where he joined forces with Lepidus and other commanders still loyal to Caesar. Six weeks later Antony re-entered Italy with 17 legions (90,000 men) and 10,000 cavalry. At that point Octavian compelled the Senate to appoint him consul, acknowledge him as Caesar’s heir and declare Caesar’s assassins outlaws. Also eager to avoid a civil war, Octavian came to an accommodation with Antony and Lepidus at Bologna, thus launching the Second Triumvirate (43–33 bc).

Having gained Antony’s support, Octavian freed himself to deal once and for all with his great uncle’s killers Brutus and Cassius. The latter duo had gathered an army of 80,000 infantry and 17,000 cavalry and crossed into Thrace. In September 42 bc Octavian and Antony moved to confront them with 100,000 infantry and 33,000 cavalry. On October 3 the armies met at the First Battle of Philippi. Octavian had taken ill, so Antony led their joint forces in a surprise attack against Cassius’ camp at the edge of a marsh. At the same time Brutus led an unexpected thrust against Antony’s left wing, broke through and seized Octavian’s camp, forcing him to flee. An oblivious Cassius, still pressured by Antony, thought the battle lost and killed himself.

Twenty days later at the Second Battle of Philippi Antony again led in the indisposed Octavian’s stead. Placing Octavian’s army at the center to focus Brutus’ attention, he advanced through the marsh to envelop the enemy commander’s left flank, taking him by surprise and forcing a rout. Brutus escaped but later committed suicide.

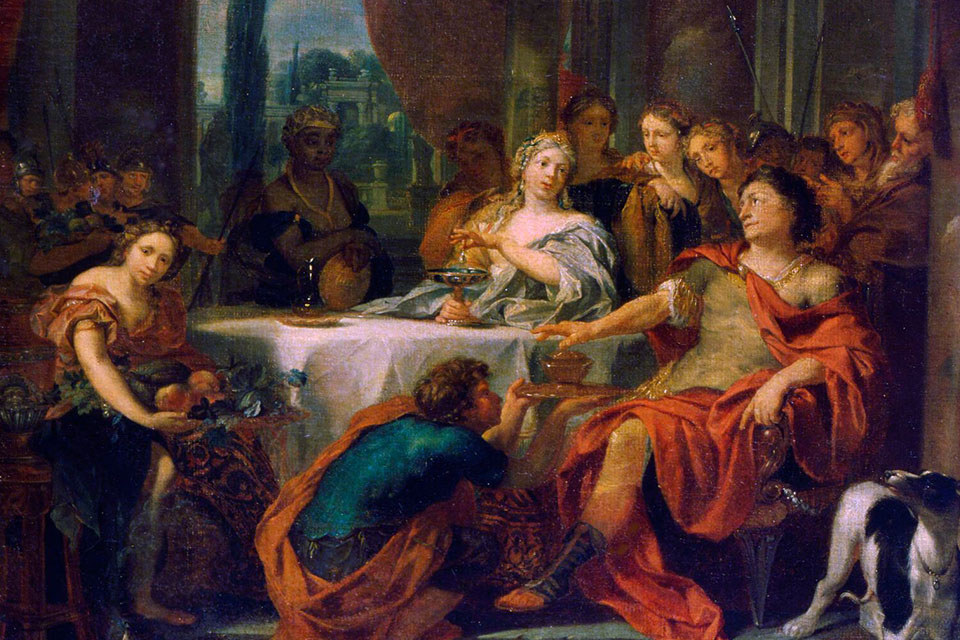

Having finally eliminated Caesar’s assassins, the triumvirs—Octavian, Antony and Lepidus—settled into their prior arrangement, Octavian and Lepidus ruling the west, Antony the east. Around 41 bc, while passing through the province of Cilicia (in present-day southern Turkey), Antony again encountered Cleopatra, who had been forced into exile by her younger brother, husband and co-ruler, Ptolemy XIII. Antony was 41, Cleopatra 18. It was a fateful meeting, launching of one of the most famous—and disastrous—love affairs in history.

Meanwhile back in Rome, Antony’s wife, Fulvia, and brother Lucius had in his absence taken up arms against Octavian. In a public rebuke of Fulvia, Antony returned to Rome and reiterated his support for Octavian. On Fulvia’s death in 40 bc Antony married Octavian’s sister, Octavia, further cementing his relationship with the future Augustus. The division of the empire was subsequently revised, Antony gaining control of everything east of the Ionian Sea, Lepidus placated with a governorship in Africa before fading into obscurity. The triumvirs also ceded territory to General Sextus Pompey, who took control of Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica and the Peloponnese.

Of course, political power is no guarantee of military control. Before leaving for Rome, Antony had appointed Publius Ventidius Bassus his proconsul in the east. In March 40 bc the Parthians had attacked Syria, reaching Antioch before Ventidius managed to drive them back out of the province. On his return from Rome, however, Antony planned a punitive invasion of Parthia, in part to recover the standards and prisoners left behind by Crassus after his disastrous 53 bc defeat and death at Carrhae. It was not one of Antony’s better decisions.

In the summer of 36 bc, having assembled an army of more than 100,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry, Antony marched through Armenia and into the Parthian province of Media Atropatene (present-day Azerbaijan) toward the capital of Phraaspa. Plutarch suggests Antony sought to end the campaign quickly, the sooner to return to Cleopatra in Egypt. As a result he pressed ahead in haste, failing to rest and refurbish his troops in Armenia after the long march from Greece. Further extending himself, Antony left his baggage train and siege engines behind, ostensibly protected by 6,000 Armenian cavalry. But when a Parthian army under King Phraates IV closed in, the Armenians bolted for home, allowing the enemy to destroy the baggage train and forcing the Roman general to abandon his siege. Worse yet, winter was approaching, and Antony was trapped, with the enemy across his line of communication and supply.

During the subsequent retreat to Armenia, the Persians relentlessly ambushed and harassed the Roman column, forcing 18 engagements in just 27 days. Antony lost some 20,000 soldiers and 4,000 cavalrymen during the campaign, many of hunger and cold during the frigid winter march through Armenia. Hearing of his misfortune, Octavia wrote to say she was sailing from Athens to console her husband. But Antony told her not to come, choosing instead to retire to Egypt with Cleopatra.

The Parthian debacle marked the turning point in Antony’s fortunes. He had failed to avenge Carrhae, and his terrible treatment of Octavia had alienated her powerful brother, Octavian. The Roman people also turned against him over his relationship with Cleopatra. Of more immediate importance, his materiel and manpower losses had crippled Antony’s military capabilities. Octavian, meanwhile, had consolidated his hold on the west, driving Sextus Pompey from the region and then pacifying Dalmatia, Illyricum and Pannonia. He upped the ante in 33 bc by launching a propaganda campaign against Antony, convincing the Senate a year later to declare war against Cleopatra and revoke her lover’s triumviral title.

Anticipating war, Antony had raised a massive army of more than 150,000 soldiers, 12,000 cavalrymen and a fleet of some 800 warships and transports. He deployed his army and fleet in and around the harbor at Actium in Greece to discourage Octavian from venturing east. Seeing the deployments as a threat, Octavian mustered his own considerable force—80,000 men, 12,000 cavalry and some 400 ships—at Brindisi. Antony should have followed the advice of his senior officers and invaded Italy, but Cleopatra was opposed to such an invasion, fearing it would leave Egypt exposed. So the Roman commander overruled his generals in what Plutarch termed “one of the greatest of Antony’s oversights.” In midsummer Octavian crossed the Adriatic without opposition and deployed his army on high ground 5 miles north of Actium.

Antony’s army was at the end of a long supply line linked to Egyptian granaries by a chain of island bases. Spotting the weakness, Octavian’s admiral, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, set about seizing the bases in turn. By September he had severed Antony’s communications and choked off his food and supplies, isolating his troops. Antony twice sought to provoke Octavian to into a land battle, but the enemy commander refused to engage. In August 31 bc Antony sent an army north to break the siege and his ships west to break the blockade, but both efforts failed disastrously. Cleopatra insisted Antony retreat, believing her 60 ships and some of Antony’s might escape to Egypt, where they could raise more troops to continue the war with Octavian.

Antony had more ships than rowers to power them, so on September 2 he burned the vessels he could not man, leaving him with 230 to Octavian’s 400. Taking Cleopatra’s advice, Antony sought to break free from his untenable position and live to fight again. His ships first engaged the Roman right, the maneuver having the calculated effect of thinning the center of the line so Cleopatra’s ships could break out and escape to the open sea. Antony soon followed. He lost 15 ships and some 5,000 sailors, with scores more captured, but almost half the serviceable fleet escaped to Egypt. The real disaster came on land. When Antony’s subordinate Canidius Crassus tried and failed to break out of the encirclement, the army mutinied and surrendered to Octavian.

Antony knew any hope of further resistance depended on his army making it back to Egypt. On learning it had surrendered, he plunged into a suicidal depression. Octavian pursued Antony and Cleopatra to Egypt. Antony’s remaining troops drove back the invaders in a brief battle at Alexandria, but Octavian renewed his attack in October, this time successfully. By then most of Antony’s men and ships had gone over to Octavian, leaving the onetime consul of Rome only a token force. Mistakenly believing Cleopatra had killed herself, Antony fell on his sword. Mortally wounded, he died in her arms, ending a life that had earlier showed such promise. That night Cleopatra took her own life.

Antony’s legacy suffered under the styli of ancient historians, all of whom were admirers of Octavian and the Augustan empire.

The most damaging claim was that Antony’s fervor for Cleopatra had driven him to war against Octavian and in turn clouded his strategic thinking. In fact, the most defensible aspect of Antony’s ragged strategy was his regard for Egypt itself. Like Octavian, he realized Rome’s very survival depended on its possession of Egypt’s grain, money, ships and manpower. Straddling the east-west trade route, Egypt was so important that Octavian, as Augustus, declared it a personal possession of the emperor, and that no Roman official could visit without his permission.

Antony doubtless would have done the same had he been victorious.

Richard A. Gabriel is the author of more than 50 books. For further reading he suggests Mark Antony: A Biography, by Eleanor Goltz Huzar, and The Life and Times of Mark Antony, by Arthur Weigall.