To preserve the Anzio beachhead against a massive German counterattack, Allied troops resorted to a brutal ground game.

There was total silence. No clank of tank tracks, no drone of aircraft engines, no thunder of distant artillery. All across the stalemated Anzio beachhead, stretching some 15 miles from east to west, it was unnervingly quiet in the early hours of February 16, 1944, as if the Germans and the Allies were in their corners, taking a deep breath and steeling themselves before the clang of the bell and the first round.

Dawn broke, a faint light spreading across the battlefield. With it came the whine of shells, followed by a metallic scream and the crumple of explosions. The air filled with sound and it seemed that immense trains were hurtling overhead, then crashing on top of one another. Men from the 157th Regiment of the 45th “Thunderbird” Infantry Division—holding positions about five miles inland, along a 2,000-yard front flanking a road connecting Anzio to Rome—were bounced around their foxholes. Dozens died from the concussive effect of nearby blasts that burst soldiers’ lungs and tore away their muddied field jackets.

After an hour, the shelling ceased. A few miles north, across a no-man’s-land of shallow ditches and draws, thousands of German soldiers checked their weapons one last time and stepped forward. Operation Fischfang—“Catch Fish”—aimed at destroying the Allied beachhead, had begun. Not since the blitzkrieg of spring 1940, when the Germans had rolled to Paris in less than six weeks, had so large an attacking force gathered to do battle in the west. The path to victory lay along the crucial route to Rome—the Via Anziate— which bisected ugly scrubland, marshes, and woods. If Wehrmacht armor could advance south along that route, the Germans would be able to push the Allies—some 100,000 men—into the Tyrrhenian Sea.

A flare soared, bathing the landscape in an eerie green. Another deafening symphony began, this time of machine guns, rifles, and mortars. In his dugout a few yards east of the Via Anziate, E Company’s commander, Captain Felix L. Sparks, picked up his field glasses and scanned the front. The tall, wiry Arizona native had first seen action in Sicily before fighting his way up Italy’s jagged spine. Now, at age 25, he was a canny veteran of three amphibious invasions and a superb company commander, much respected by his men. He was also surprisingly calm in combat. But what Sparks saw tested his composure. Several mottled gray Mark IV and Mark V Panther tanks, spewing clouds of exhaust, were about a mile away, trundling down the roadbed toward his company.

Behind the lumbering 25-ton behemoths of the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division came hundreds of gray-uniformed men, some drunk and drugged, screaming guttural orders, blowing whistles, barking encouragement to one another. Some were singing beer hall songs learned in the Hitler Youth. They belonged to the first wave of assault troops from the experienced 715th Infantry Division. The division was part of the German Fourteenth Army, under the command of the highly capable general Eberhard von Mackensen, who answered to master strategist Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, commander of German forces in Italy.

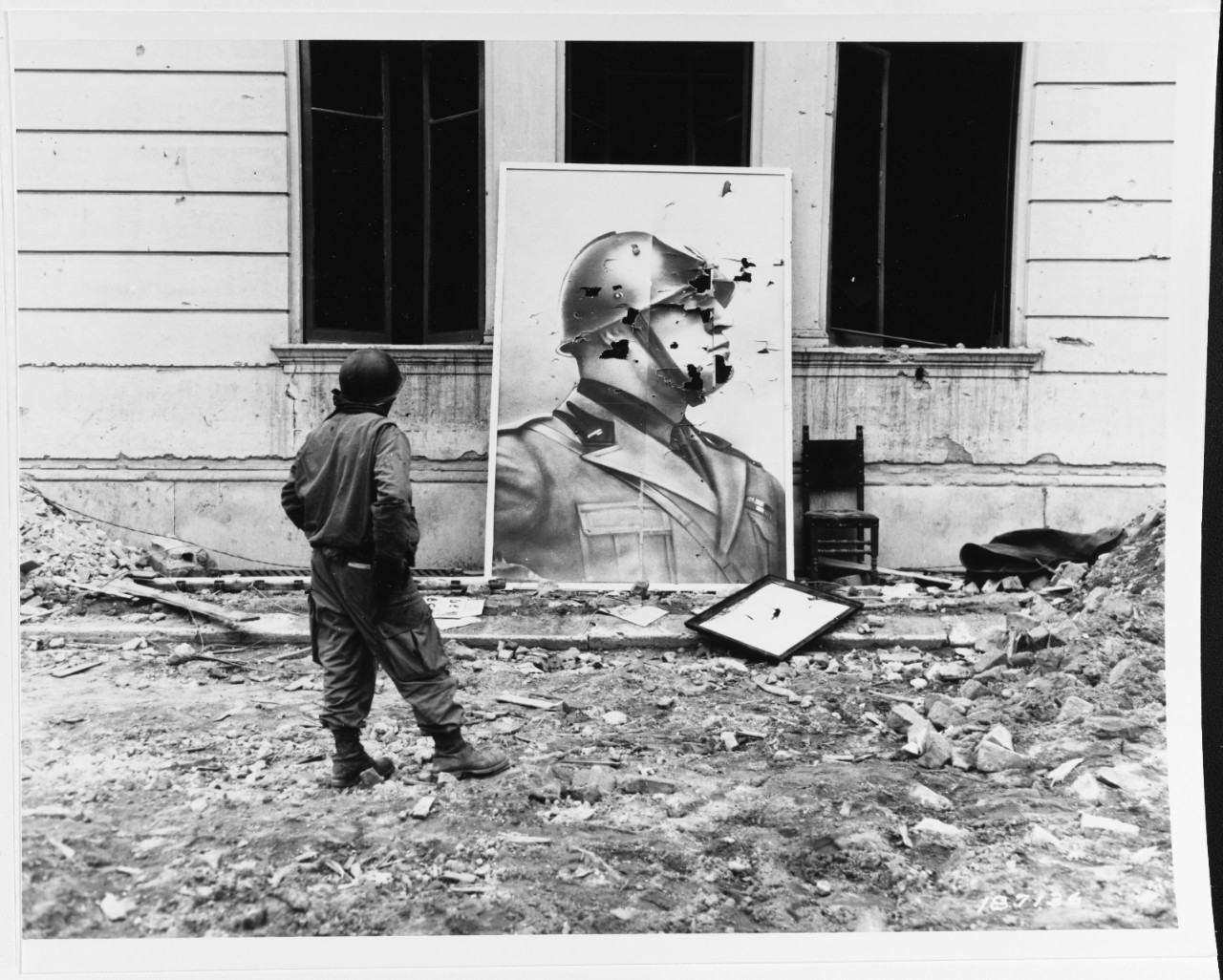

As far as the attacking Germans were concerned, Sparks’s company occupied the Schwerpunkt: the crucial point at which to concentrate their energies to break through. Their officers had correctly told them that the Americans standing in their way were a National Guard outfit. The 45th Infantry Division had been formed from the Oklahoma Army National Guard. The officers also correctly noted that many in the unit were Native Americans. One German report called these GIs “racially inferior people who had no love of the white man and probably wouldn’t fight.” The German troops could taste victory. They didn’t have far to push, either: just five miles and the Allies would be back in the Mediterranean.

Sparks peeked out of his foxhole again. Three Panzer IVs were on his left flank, avoiding the Via Anziate. Their commanders knew that if they took the road American artillery fire would zero in and destroy them. The tanks were coming fast, only 200 yards away. Machine guns blinking streams of bullets, they sliced through one platoon of Thunderbirds like a scalpel.

Two M10 tank destroyers were nearby.

“Get them!” Sparks called to the crew.

The officer in charge of the tank destroyers hesitated.

“Are those British tanks?” he asked.

“Hell, no—they’re German tanks!” shouted Sparks. “Shoot them!”

The M10s fired. Two of the enemy tanks exploded, their inch-thick armor shredded. The third tank pulled back.

One M10 moved 30 yards to the east of the Via Anziate and stopped near Sparks’s foxhole. Sparks figured its commander wanted to gain a better line of fire. A shell shrieked, exploded, and the M10 erupted, killing its crew and sending flames shooting into the sky. To avoid being burned, Sparks had to jump to another foxhole.

He looked north, along the Via Anziate. Hundreds of German soldiers were closing on E Company’s positions. Sparks gave the order to fire. Machine guns snarled. Snipers picked off German officers. M1 rifle fire crackled, interrupted by barely audible pings as soldiers emptied their magazines. Sparks’s machine gunners soon had mowed down most of the first wave. Germans fell in agony, their bodies piling so thickly in places that American marksmen could not see to shoot.

A few Germans survived the hail of fire, including one who got within yards of Sparks’s foxhole. An American sergeant had strapped himself to a tank destroyer’s .50-caliber machine gun mount. The sergeant opened up, killing most of the attackers. But one remaining German, armed with a submachine gun, crawled toward the tank destroyer. There was a brrrrrp sound. Dust flew from the back of the sergeant’s field jacket as bullets riddled his chest. Another American put the German out of action. Several corpses lay at the edge of Sparks’s hole; the sergeant had saved his life.

Again shellfire erupted, hitting another M10, which burst into flames. Explosions ripped through E Company, killing a platoon leader and an entire 12-man rifle squad and knocking out the company’s antitank guns. More German tanks closed in, blowing Sparks’s troops from their holes at close range.

“Medics!” men cried. “Medics!”

The situation seemed hopeless. Sparks faced a tough decision. He could stall the German attack by ordering his own artillery to fire on his positions. Some of his men might be killed, but “pulling the chain,” as it was called, was his only option. Even so, it was a desperate move.

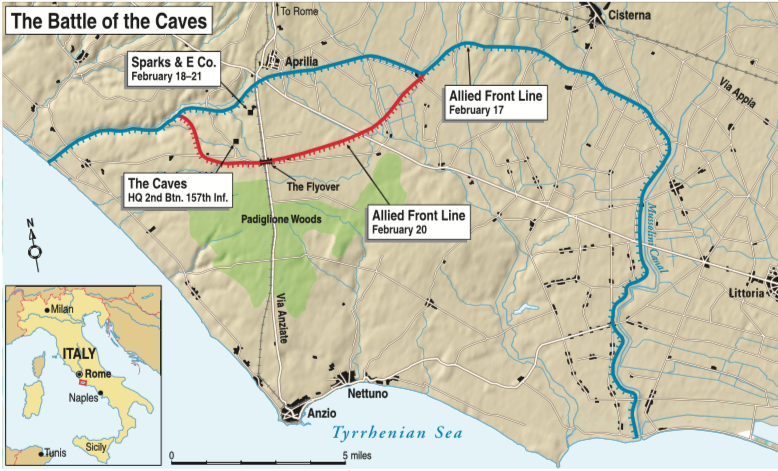

The 158th Artillery responded, shells exploding with devastating power among the Thunderbirds and forcing German tanks and infantry to withdraw. But elsewhere along the front the enemy advance continued, breaking through Allied lines. To the west, the 179th Infantry Regiment pulled back, unable to hold the rushing waves of Germans. In the east, British forces from the 56th Division also withdrew. Seven enemy divisions were pushing south across the Anzio plain, an area the Italians had grimly called Campo di Carne—“Field of Meat.”

The Thunderbirds, who manned a six-mile sector of the front, had borne the brunt of the attack. The three Thunderbird regiments took unprecedented losses—especially along the Via Anziate. At dawn, Sparks had commanded 230 men; now he had fewer than 130.

In his headquarters 50 miles to the north in Rome, Albert Kesselring studied dispatches and reports from Anzio that evening and noted how fast the battle was consuming arms and assault units. He ordered von Mackensen, Operation Fischfang’s commander, to commit his reserves. The Germans had to split the 45th Infantry Division in two. “Smiling Albert” did not want to have to inform the Führer that his forces had failed to break through.

An hour before dawn on February 17, German flares suddenly turned the skies above the Anzio beachhead as bright as day. An ominous drone followed, and then Allied troops heard the offbeat throb of bombers’ engines. Jaw-jolting explosions destroyed mortar emplacements and machine-gun nests along the Allied front, hitting the 157th’s command post and demolishing a house occupied by headquarters staff, severing communications with the 2nd Battalion command post.

More German planes hit the rear, dropping thousands of antipersonnel butterfly bombs, whose brightly colored fins whirled as they fell. Kesselring was emptying his arsenal at the battered Allied lines.

Panzers coughed to life, filling the chill air with black fumes. German soldiers shouldered their weapons, and in the early light set out along the Via Anziate, determined to destroy what was left of the Thunderbirds’ lines. But to Sparks’s astonished relief, the Germans did not try to storm his position. Instead, with tanks in support, the enemy troops moved west, where they broke through the 179th Infantry’s lines. “They didn’t even shell us,” Sparks recalled. “But they were [soon] all around us and in back of us. They had already learned that if they did attack, we’d bring in artillery fire. So they gave our position a wide berth.”

All that morning, Germans poured past, a seemingly unstoppable flow of force.

“It looks like a parade,” one man said.

The remnants of E Company were stranded, with only two M4 Sherman tanks left. There was also a lone bazooka. A corporal named George Holt had carried the antitank weapon all the way from Salerno and never had an opportunity to fire it, much to everyone’s amusement.

Around noon, Sparks sent a runner to the 2nd Battalion command post, about a mile to the south. The command post was sheltered in an extensive centuries-old warren of caves and man-made tunnels big enough to drive a truck through. (See “Return to the Caves,” page 41.) The caves were also the base for the 158th Artillery’s radio crew. The runner informed the 2nd Battalion’s recently appointed commander, Lieutenant Colonel Laurence C. Brown, that E Company’s current position was untenable.

“Withdraw and set up on the battalion right flank on the highway,” Brown responded.

On the map Sparks held, he could see a small rise to his rear, roughly 400 yards down the Via Anziate. The two Shermans would attract enemy fire, so he ordered the tank crews to wait until he and his men pulled back before making their break. Just as the withdrawal began, Sparks saw a German Mark IV moving along the road. It turned and headed down a dirt track, directly toward his command post. Then he remembered Holt and his bazooka.

Holt was in a foxhole 10 feet away.

“Holt, get that tank!”

Holt fired and missed. The tank wheeled, its massive tracks clanking, and pulled back. Sparks shouted for Holt to reload. There was no reply. Had Holt heard him? Sparks sprinted to the corporal’s foxhole. Holt had collapsed. He was bleeding from the nose and appeared to be suffering from an exploding shell’s concussion.

Sparks ordered Holt and other wounded men evacuated. Then he and the remaining 18 members of E Company set out south along the Via Anziate. They tried to stay low, but the enemy quickly spotted them; 50 Germans attacked from the rear. The Thunderbirds kept moving, kept firing, and were down to their last clips when, once more, the Germans backed off. Exhausted, Sparks and his men stumbled up a small rise to the west of the shell-pocked road and dug in. They had no choice but to leave the badly wounded behind.

Sparks knew every one of those men by name.

Dusk settled. One of Sparks’s men spotted about 200 heavily armed German soldiers heading toward the 2nd Battalion command post. Sparks’s communications sergeant, Fortunato Garcia, quick-crawled toward the caves as the last of the daylight faded. He managed to get there in time to issue a warning. Seconds later, German grenades exploded in the caves’ entrances, killing a soldier and destroying a radio.

Thunderbirds near the caves replied with M1s, machine guns, and grenades. Men inside also fired back, every rifle shot echoing through the underground chambers like cannon fire. But the Germans kept coming.

The defenders ran so low on ammunition they resorted to stripping rounds from discarded machine-gun belts to fill M1 clips. The battalion’s liaison officer for the 158th Artillery, Captain George Hubbert, called artillery fire onto the caves. Several batteries’ gun crews, blackened from cordite powder and almost deaf from incessant firing, loaded more shells into their howitzers’ waist-high breeches and fired, tossing the brass casings onto small hills of spent shells as ginger-colored smoke drifted though nearby trees. Allied white phosphorous shells, landing around the caves for 30 minutes, added to the mayhem, stunning those inside but killing most of the attackers.

All night dying Germans, surrounded by torn and bullet-riddled comrades, moaned and cried.

“Kamerad, Kamerad,” voices cried out.

“Don’t shoot; I’m your friend,” others cried in English.

Near the caves, a Thunderbird machine gunner spotted a wounded German trying to crawl to safety.

“There’s a Heinie,” he told a rifleman. “Pick him off.”

“I don’t see him. Where is he?”

“Gimme your rifle and I’ll show you.”

The rifleman handed over his M1. The machine gunner aimed and fired.

“Now I see him!” said the rifleman. “He just moved.”

“Yeah,” the machine gunner said. “I just moved him.”

At noon on February 18, 3rd Division commander Major General Lucian Truscott arrived in the wine cellar in the village of Nettuno—three miles northeast of Anzio—that served as headquarters for the Allied forces there. A situation map showed the extent of German penetrations in the last 48 hours. Kesselring, spending his reserves at a rapid rate, had pushed only as far as an overpass on the Via Anziate called the Flyover, two miles to Sparks’s rear.

Truscott, clad in a leather jacket and tanker’s boots, examined the map. Lines in red showed German advances; the Allied positions were in blue. Redrawn many times, the map was badly smudged. In the center was a blue circle around the caves, where the remnants of the regiment’s 2nd Battalion were surrounded.

All afternoon the battle raged across the beachhead’s perimeter. But nowhere was the fighting as savage and critical as it was in the 45th Division’s sector at the center of the Allied line. In one 40-minute spell, an incredible 600 rounds of enemy artillery landed around E Company’s isolated position beside the route to Rome, shells exploding every four seconds. The barrage killed three men, leaving Captain Sparks and 15 others huddled in foxholes, hands over ears, hearts racing.

Still, most Thunderbirds held steady into the evening and through the long night. By the next morning, February 19, interlocking American machine-gun fire from a ridgeline near the caves had killed a cluster of Germans by one of the entrances— their bodies falling, macabrely, in the shape of a cross.

Allied artillery, which had outfired the enemy by a factor of 10, finally halted Kesselring’s forces. Shell-shocked Germans began surrendering in droves. In one sector, German officers ordered machine-gun and mortar units to fire on any fellow soldier trying to give up without a fight. Under interrogation, POWs later confirmed the horror of the Allied shelling. Germans told of making attacks “starting out in battalion strength,” one Thunderbird recalled, but then “being whittled down to less than the size of a platoon by our artillery before reaching our forward positions.”

In a large map room at Adolf Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair headquarters in East Prussia, the Führer seethed with frustration. Operation Fischfang was not going according to plan. The Allies had not been pushed back into the sea. The abscess below Rome had yet to be lanced. He began to rant about his generals in Italy. They were the problem, not his brave troops. After a 20-minute tirade, his voice grew calmer. Another all-out attack might do the trick. And if his useless generals failed again, he would command the battle himself.

Before dawn on February 20, Captain Sparks sent a runner to the caves to find out what the 2nd Battalion planned to do next. He and his men were out of supplies and low on water, scavenging for ammunition on the ground. Sparks had not eaten for days. When the runner returned, he reported that some 500 men from the British 2nd Battalion of the Queen’s Royal Regiment of the 56th Division were to relieve the 2nd Battalion the night of February 21.

Sparks thought that was one of the stupidest things he had ever heard. He and his battalion were surrounded, yet hundreds of British troops were being sent to relieve them. How could relief troops get to the caves, let alone hold out once they arrived? The sensible course was to pull back and reinforce the regiment’s new front line—not waste yet more good men in the defense of a hopeless position.

The runner also told Sparks to prepare to pull back to the caves, now about three-quarters of a mile away. Once the British arrived, he and the surviving Thunderbirds in the 2nd Battalion were to make a break for the regiment’s forward lines, two miles further to the rear.

The British set out after dark on February 21, moving anxiously forward, rifles slung, beneath the brilliant green light of seemingly constant enemy chandelier flares. A German plane swooped and dropped butterfly bombs. They made hideous popping sounds as they exploded in blinding orange and white splashes, and left dozens of British troops dead and more wounded. By the time the hundred or so soldiers who survived reached the caves, they were without most of their weapons, armor, and supplies. But to the Thunderbirds’ amazement, the British insisted on taking over the Americans’ positions.

Later that night, two British rifle squads set out from the caves to relieve Sparks and company; fewer than a dozen men made it to the Americans’ position. Sparks said they could borrow his last machine gun, emphasizing that he would come back for it. To stand a chance of crossing no-man’s-land, he would need all the firepower he could carry.

Around dawn on February 22, Sparks and his men departed for the caves, slithering on their stomachs and crawling through icy puddles in the darkness back to the command post, where help awaited. Inside, a veritable Hades greeted them. At every turn, men with terrible wounds, heavily drugged to stop their screams, lay on bloody stretchers; medics and the battalion surgeon, Captain Peter Graffagnino, worked tirelessly, but stocks of morphine spikes, bandages, and water were running low.

First Sergeant Harvey E. Vocke and a few others dared to fetch water from a nearby stream that was clogged with dozens of decaying enemy corpses. The Germans opened fire, and machine-gun bullets knocked water cans from Vocke’s hands. Others were more successful. They filled their canteens and returned to the caves, where they boiled the bloody water and shared it with the wounded.

It was time to move out. Around 1:30 a.m. on February 23, able-bodied survivors from the 2nd Battalion shouldered arms, said last prayers, and formed a line leading to the mouth of the caves. Captain Graffagnino and several medics volunteered to stay behind with the wounded. What lay ahead, the departing men understood only too well, would be the greatest test of their lives: crossing more than two miles of enemy territory dotted with German machine-gun nests.

As Sparks prepared to leave the caves, he heard fighting outside and remembered the machine gun he had left with the British. He found the 2nd Battalion commander near the entrance and told Colonel Brown he was going to get the gun. The battalion’s planned escape route led across a bridge that spanned a deep draw; “I’ll meet you at the bridge,” Sparks said.

Then he slipped out, taking only his .45 sidearm, groping in the dark through draws and gullies 400 yards north to his old position near the Via Anziate. To his shock, no one was there. The rise had been abandoned; his machine gun was gone. Spooked, Sparks worked his way back and eventually rejoined a group of about 50 departing Thunderbirds. Among them was Sergeant Garcia, who days earlier had warned men in the caves of the oncoming Germans. Sparks decided to lead the way. Terrified men, several of them walking wounded, followed him in single file, stumbling over brambles, discarded equipment, and corpses old and new.

Sparks reached the bridge and led some of the men across it. Others lagged, and Sparks returned to make sure the stragglers got across. Then he moved forward once more, down a supply trail. The ravenous Sparks spotted some biscuits and a canteen that a British soldier had dropped; he stuffed his mouth full of dry pastry and washed it down with the clean water. When he came across a rifle he grabbed that as well.

A cold rain fell, soaking Sparks’s dirty, slicked uniform. Garcia volunteered to scout ahead and took off into the darkness. He did not return.

Sparks heard the distinct sound of a German machine gun— like fabric being torn close to his ear. Then the night fell silent. He stood stock-still for a few moments, listening, before crawling forward again. When he caught up with the column, he saw that several men had been cut down. Others had scattered. A few lay nearby, frozen with fear.

A machine gun sounded again.

Bullets cracked through the cold air.

“Fire back! Fire back!” Sparks ordered.

Several men did.

“Everybody follow me!” he shouted.

He crawled forward with a few men behind him. He knew there was a canal nearby where they could take cover. The steep banks were matted with vegetation. Sparks dropped into the foul, shin-deep water. Others scrambled down after him. He took a head count. A few minutes ago, he had been leading about 40 men. Now there were just 12, none of them from E Company. He figured the rest were dead or captured.

Sparks started forward again, moving along the canal toward German lines, which had shifted two miles closer since the enemy counteroffensive began. He sensed danger in one direction, trusted his instinct, and led the survivors down another path. They tried to be as silent as possible, but soon German voices cried out and grenades exploded nearby, fountains of earth cascading into the sky. But the Germans still could not see them, and no one was hurt. They scrambled through the German lines and into no-man’s-land.

In the gloom Sparks could see figures ahead: British troops. He had no password. If he called out would they open fire? The artillerymen spotted him and, to his astonishment, fled into nearby woods, horrified by the sight of mud-coated madmen emerging from the murk.

Dawn had broken by the time Sparks finally reached his regiment’s headquarters. He could barely stand as he reported to the 157th’s commanding officer, Colonel John Church, on the battle by the Via Anziate and the subsequent breakout. Sparks was still carrying his pistol and salvaged rifle when he finally lay down in a foxhole. There he slept, undisturbed, for more than 24 hours.

The Thunderbirds had saved the Anzio beachhead, but suffered mightily to do so. The division lost half its strength in only 36 hours. The 157th’s 2nd Battalion endured 75 percent casualties. On February 16, it had numbered 713 enlisted men and 38 officers; now there were 162 men and 15 officers. Ninety of these men needed immediate hospitalization. Many had lost their hearing because of the constant din of artillery fire and the echo-chamber effect of the caves. Several had trench foot so severe they could not walk and had to have legs amputated. The British battalion that relieved the Thunderbirds in the caves fought against all odds for three more days before being all but destroyed. Surgeon Peter Graffagnino and the medics who stayed behind with the wounded in the caves spent the rest of the war as POWs in Germany.

Felix Sparks awoke believing he was E Company’s sole survivor, until he learned that another E Company man, Platoon Sergeant Leon Siehr, had survived as well—making them only two of 231 men in their unit that February to make it back to Allied lines from what became known as the Battle of the Caves.

Originally published in the April 2014 issue of World War II. To subscribe, click here.