I’d seen that name before, of course; indeed, I had stepped over it several times a day going in and out of my apartment building’s elevator. But I’d never thought about the person behind the company or, frankly, the history of elevators. To me they seemed like little more than a nifty convenience. And Otis, I knew, hadn’t even invented the elevator. European castles and monasteries atop steep mountains used pulleys and large rope-drawn baskets big enough to hold a person as far back as the medieval period, and Henry Waterman constructed an elevator-like mechanism in 1850, although its intended passengers were barrels and other bulky goods. Then Elisha Otis came along and, I learned, did more than just improve the design: He transformed the world.

Otis hailed from Halifax, Vt., just above the Massachusetts border, but there’s nothing in the town to commemorate its most famous son. Connie Lancaster, a local historian, who helped me piece together the paper trail that led to Otis’ birthplace, and Laura Sanders, town clerk since 1967, organized a visit to the site for me.

We meet at the town hall and make our introductions before piling into Laura’s car and hitting the road, turning left onto Branch then right onto Brook. After about two miles Brook ends at Green River Road. We turn right and head four miles to Perry Road, where we park. This is as far as we can drive.

“It’s about a three-quarter-mile walk through the woods,” Connie says.

I’m warned that there’s poison ivy along the trail, and, while looking down, I notice bizarrely shaped animal tracks.

“Those are moose prints,” Laura tells me, “and they’re fresh.”

“I’ve never seen a moose before. I’m guessing they’re pretty harmless?”

“They’ll attack if they’re in rut.”

“In a rut? You mean, like, depressed?”

“In rut. It means they’re looking to mate.”

Laura cautions me to be careful of the widow-makers—the large broken maple limbs dangling precariously above us. As I’m simultaneously watching out for poison ivy, moose in heat and falling branches, I see Connie stop for a moment and check her map.

Laura cautions me to be careful of the widow-makers—the large broken maple limbs dangling precariously above us. As I’m simultaneously watching out for poison ivy, moose in heat and falling branches, I see Connie stop for a moment and check her map.

“Found it!” she calls out. From where we’re standing, I can see a long, squat stone wall about 40 feet away. Broken steps lead up to what would have been an entrance to the old house, and there’s a hearth and central chimney with a root cellar several feet below.

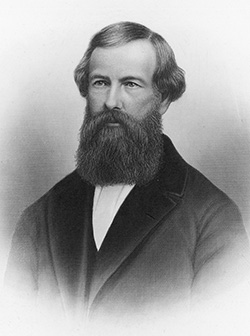

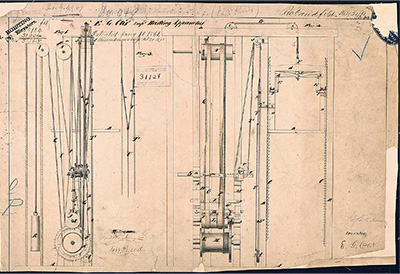

Elisha Graves Otis was born here on August 3, 1811, the youngest of six children. He mastered woodworking and engineering skills on the family farm, and at 19 started bouncing between New York and Vermont, dabbling in carpentry, operating his own gristmill, running a freight-hauling business and manufacturing high-end carriages. In 1845 he settled in New York with his second wife (his first had died in 1842) and two young sons, Charles and Norton, and was eventually hired by a bedstead manufacturing company to oversee the installation of all machinery in its new factory. To raise heavy equipment and lumber from floor to floor, Otis erected a Waterman-type hoist. Nothing fancy or unique at first. But he knew these lifts were inherently dangerous—ropes could break, sending workers plummeting to their deaths—so Otis jerry-built vertical safety brakes using a wagon spring, rope and ratcheted guide rails for the hoist platform. In 1852 he built two “safety hoisters” for his employer, Benjamin Newhouse, and a third for a neighboring company impressed with the concept.

Newhouse soon closed the bedstead operation, and Otis incorporated the E.G. Otis Company to design and build safety hoists, for lifting not only goods and supplies but people. There were, alas, no takers, and by the end of 1853 he had a total inventory worth $122.71, including two oil cans, a secondhand lathe and the accounting ledger that recorded his measly earnings. Otis, doubtful he could overcome the public’s fear and distrust of the earlier, notoriously accident-prone mechanisms, considered heading west to capitalize on the Gold Rush.

Enter P.T. Barnum, who was enthralled by Otis’ innovation. In 1854 Barnum paid Otis $100 to stand on an elevator platform suspended by a single rope high above gathering onlookers inside the Crystal Palace, constructed for the 1853 World’s Fair in New York. Barnum’s showmanship was infectious; the normally unpretentious Otis doffed a top hat and, after a short pause to ensure that he had the crowd’s rapt attention, ordered an ax-wielding assistant to cut the rope. When it snapped, the platform plunged—about two feet. Spring-released brakes automatically locked, and Otis calmly assured the relieved spectators, “All safe, gentleman. All safe.”

At last he was in business. After fulfilling orders for about three dozen freight lifts, Otis installed the world’s first safe passenger elevator on March 23, 1857, inside E.V. Haughwout & Co.’s Manhattan chinaware and glass emporium at 488 Broadway (now a registered landmark). Demand grew and Otis was finally seeing years of hard work come to fruition.

And then on April 8, 1861, 49-year-old Elisha Otis died of diphtheria, leaving the company in the hands of his two sons. Fortunately, they proved even more adept at business than their father. Charles and Norton weathered the economic slump during the Civil War and oversaw exponential growth in its aftermath.

Otis’ safety elevators doubled or tripled building heights. “Those who remember the Broadway of twenty years ago can hardly walk the street now without incessant wonder and surprise,” Harper’s magazine observed soon after Otis died. “The transformation…is always going on before the eye. Twenty years ago it was a street of three-story red brick houses. Now it is a highway of stone, and iron.”

By 1872 there were 2,000 Otis Brothers & Co. elevators in service. Theirs was the brand of choice in finer hotels, high-rise apartments and stores nationwide, although they did have competitors. One company believed that an airtight shaft would prevent an elevator from crashing more effectively than a braking system. Theoretically, the falling car would eventually slow to a halt on a cushion of air. When, during a demonstration, the test car came screaming down to ground level carrying eight brave passengers, it blew out the first floor doors, injuring—but thankfully not killing—everyone inside. The company quickly went out of business.

Otis expanded abroad, and an early assignment included the Eiffel Tower, opened in 1889 in celebration of the French Revolution’s centenary. Otis was selected over European engineers because it could best solve the challenge of installing elevators within the tower’s curved legs. One by one other prestigious landmarks installed Otis elevators, carrying the brand into the 21st century: the Kremlin, Vatican, Empire State Building, United Nations, Kennedy Space Center, World Trade Center, Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro, Shanghai World Financial Center and Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which is currently the tallest building in the world. Steam and hydraulic-powered motors have given way to electric and computerized systems, and time- and life-saving features have appeared incrementally. Fatal accidents happen, but very rarely. On average, 26 people are killed by elevators each year—car crashes, by comparison, account for the same number of fatalities every five hours—and repairmen are the most likely victims. When something does go wrong, however, it goes hideously wrong, as any online search using the keywords “elevator” and “decapitations” will attest.

Otis expanded abroad, and an early assignment included the Eiffel Tower, opened in 1889 in celebration of the French Revolution’s centenary. Otis was selected over European engineers because it could best solve the challenge of installing elevators within the tower’s curved legs. One by one other prestigious landmarks installed Otis elevators, carrying the brand into the 21st century: the Kremlin, Vatican, Empire State Building, United Nations, Kennedy Space Center, World Trade Center, Christ the Redeemer statue in Rio de Janeiro, Shanghai World Financial Center and Burj Khalifa in Dubai, which is currently the tallest building in the world. Steam and hydraulic-powered motors have given way to electric and computerized systems, and time- and life-saving features have appeared incrementally. Fatal accidents happen, but very rarely. On average, 26 people are killed by elevators each year—car crashes, by comparison, account for the same number of fatalities every five hours—and repairmen are the most likely victims. When something does go wrong, however, it goes hideously wrong, as any online search using the keywords “elevator” and “decapitations” will attest.

Laura starts rallying us back to her car so I don’t miss my flight from Boston. I thank them for their help, and we discuss the need for a marker in the vicinity of Otis’ birthplace—closer to Perry Road than way out in the woods where no one would see it.

With exactly two hours to make the two-hour trip, I race to Logan Airport. Having lived in Massachusetts as a kid, I’ve seen the Boston skyline hundreds of times flying in and out of Logan, and long ago I lost that sense of awe when a plane rises over a city, especially after sunset. But tonight, with my forehead pressed against the plastic window, I’m newly transfixed by the expanding grid of blinking, multicolored lights below, and I think of other favorite skylines—Manhattan, Chicago, Los Angeles, Dallas, Miami—I’ve seen. All of them, and thousands more across the globe, sprouted up because of Elisha Otis. A subsidiary of United Technologies since 1976, the Otis Elevator Company remains unmatched in size and reach, carrying the equivalent of the world’s population every four days on 2.3 million elevators and other people movers in 200 countries and territories. No other form of public transportation comes close.

Elisha Otis underestimated how drastically his work would reshape the global landscape; he didn’t bother to patent his innovation for seven years, an eternity in patent registration. (And having already filed numerous other patents for railcar brakes, a steam plow and a bake oven, Otis wasn’t exactly ignorant of the process.) But he was lucky. During those seven years, none of his competitors thought his automatic safety elevator idea was worth stealing, replicating or patenting either.

If you would like to share a little-known site where history happened, please visit www.HereIsWhere.org.